Community and the Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relax Dont Panic Book.Indd 1 09/04/2014 06:51 Relax Dont Panic Book.Indd 2 09/04/2014 06:51 Really, Don’T Panic!

REALLY, Don’t PANIC! relax dont panic book.indd 1 09/04/2014 06:51 relax dont panic book.indd 2 09/04/2014 06:51 REALLY, Don’t PANIC! POSITIVE MESSAGES FOR SOUTH AFRICANS, BY SOUTH AFRICANS ALAN KNOTT-CRAIG relax dont panic book.indd 3 09/04/2014 06:51 © Various contributors, 2008 and 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission from the copyright holder. ISBN: 978-1-920434-85-4 e-ISBN: 978-1-920434-86-1 First edition, first impression 2014 Published by Bookstorm (Pty) Ltd PO Box 4532, Northcliff 2115, Johannesburg, South Africa www.bookstorm.co.za Distributed by On the Dot www.onthedot.co.za Edited by Sean Fraser Proofread by Wesley Thompson Cover design by mr design Book design and typesetting by René de Wet Printed by Creda Communications, Cape Town relax dont panic book.indd 4 09/04/2014 06:51 CONTENTS Publisher’s preface 7 Introduction 9 Introduction to Don’t Panic (2008) 13 The email that started it all… 15 Contributions from South Africa 19 The last word 101 Where to from here? 109 Acknowledgements 111 relax dont panic book.indd 5 09/04/2014 06:51 relax dont panic book.indd 6 09/04/2014 06:51 Publisher’s PREFACE In 2008 Alan Knott-Craig compiled the first Don’t Panic as a response to the overwhelming reaction he received to an email sent to staff at iBurst, where he was MD at the time. -

Ambassador from Rochester Hold Annual Meeting at UR

The Rochester AlumniArAlumnae Reuiew DISTRIBUTED AMONG THE GRADUATES AND UNDER-GRADUATES OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER Published quarterly, in February, May, August and November by the University of Rochester for the Associated Alumni and the Alumnae Association at the Cayuga VOL. XIII, o. 2 Press, Ithaca, . Y. Editorial Office, 15 Prince St., Rochester 3, . Y. Co-editors: FEBRUARY, 1952 Charles F. Cole, '25, and Warren Phillips, '37. Application for second class reentry pending at Ithaca, . Y. President de Kiewiet Given Historic Martin B. Anderson Desk ALTHOUGH the mystery of its disappearance from Anderson Hall many decades ago is still unsolved, the historic desk of Martin B. An derson, Rochester's first president, has been returned to the University. It was discovered, under unex plained circumstances, in the engi neering department of Cornell Uni versity, where it i known to have been for some 30 years. How it got there is conjectural. It was identi fied by a brass plate with the inscrip tion: Working desk of Martin B. Ander son, LL.D., First President of the University of Rochester. When Cornelis W. de Kiewiet, act ing president of Cornell, became president of Rochester, some of his colleagues at Ithaca who knew of the desk's presence on the Cornell cam pus, decided that it should be pre sented to him and returned to Roch ester. They had it restored to its or iginal condition, and the d sk, a large and handsome double-sided one of chestnut, with top and drawer mouldings stained walnut, now President de Kiewiet checks through his brimming engagement book at his "new" 100-year-old desk in his Babcock House study. -

Sir George Grey and the British Southern Hemisphere

TREATY RESEARCH SERIES TREATY OF WAITANGI RESEARCH UNIT ‘A Terrible and Fatal Man’: Sir George Grey and the British Southern Hemisphere Regna non merito accidunt, sed sorte variantur States do not come about by merit, but vary according to chance Cyprian of Carthage Bernard Cadogan Copyright © Bernard Cadogan This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without the permission of the publishers. 1 Introduction We are proud to present our first e-book venture in this series. Bernard Cadogan holds degrees in Education and History from the University of Otago and a D. Phil from Oxford University, where he is a member of Keble College. He is also a member of Peterhouse, Cambridge University, and held a post-doctoral fellowship at the Stout Research Centre at Victoria University of Wellington in 2011. Bernard has worked as a political advisor and consultant for both government and opposition in New Zealand, and in this context his roles have included (in 2011) assisting Hon. Bill English establish New Zealand’s Constitutional Review along the lines of a Treaty of Waitangi dialogue. He worked as a consultant for the New Zealand Treasury between 2011 and 2013, producing (inter alia) a peer-reviewed published paper on welfare policy for the long range fiscal forecast. Bernard is am currently a consultant for Waikato Maori interests from his home in Oxford, UK, where he live s with his wife Jacqueline Richold Johnson and their two (soon three) children. -

INSIDE: the HISTORY of the MARSHALS Page 6 | Features a MESSAGE from PRESIDENT SELIGMAN Page 9 | Opinions the BEST of ATHLETICS Page 12 | Sports

CampusSUNDAY, MAY 17, 2015 / COMMENCEMENT ISSUE Times SERVING THE UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER COMMUNITY SINCE 1873 / campustimes.org INSIDE: THE HISTORY OF THE MARSHALS Page 6 | Features A MESSAGE FROM PRESIDENT SELIGMAN Page 9 | Opinions THE BEST OF ATHLETICS Page 12 | Sports In a photo originally taken in May 1953, Commencement Marshal and Professor of English George C. Curtiss walked toward Rush Rhees Library “toting mace for the last time.” Approximately 11 faculty members have been Commencement Marshal since 1935. PHOTO COURTESY OF ROCHESTER REVIEW AND RIVER CAMPUS LIBRARIES PHOTO ILLUSTRATION BY AARON SCHAFFER / EDITOR-IN-CHIEF PAGE 2 / campustimes.org NEWS / SUNDAY, MAY 17, 2015 COMMENCEMENT CEREMONIES THE SCHOOL OF NURSING THE COLLEGE OF ARTS, SCIENCES & ENGINEERING FRIDAY, MAY 15, 1:00 P.M. THE SCHOOL OF MEDICINE & DENTISTRY SUNDAY, MAY 17, 9:00 A.M. KODAK HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC MASTER’S DEGREE EASTMAN QUADRANGLE, RIVER CAMPUS SATURDAY, MAY 16, 12:15 P.M. KILBOURN HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC THE EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC THE SCHOOL OF MEDICINE & DENTISTRY SUNDAY, MAY 17, 11:15 A.M. FRIDAY, MAY 15, 4:00 P.M. KODAK HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC KODAK HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC THE MARGARET WARNER SCHOOL OF EDUCATION & HUMAN DEVELOPMENT SATURDAY, MAY 16, 2:30 P.M. THE WILLIAM E. SIMON SCHOOL DOCTORAL DEGREE CEREMONY KODAK HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION SATURDAY, MAY 16, 9:30 A.M. SUNDAY, JUNE 7, 10:00 A.M. KODAK HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC KODAK HALL, EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC COLLEGE DIPLOMA CEREMONIES DEPARTMENT LOCATION TIME (SUNDAY, MAY 17) African and African-American Studies Gamble Room 2:00 P.M. -

Page 1 Historical Papers Research Archive, University of The

Historical Papers Research Archive, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg G U I D E T O T H E A R C H I V E S A N D P A P E R S (Excluding the archives of the Anglican Church of Southern Africa) Copyright: Historical Papers Research Archive, University of the Witwatersrand Library PREFACE The University of the Witwatersrand has, as one of its most valuable and prestigious heritage and research assets, the holdings of the priceless Historical Papers collections. Historical Papers is the main humanities archival research resource on campus and is located in the William Cullen Library. It is also the largest non-state archives in Southern Africa and it is uniquely positioned within the South African heritage sector. The archives held in custody for the wider community within Historical Papers are extensive and provide a unique documentary record of South African history and society. The collections housed at Historical Papers include diaries, letters, memoranda, reports, minute-books, press clippings, pamphlets, photographs, drawings, oral interviews, trial transcripts and financial, legal and personal documents. These items are described in the Guide to the Archives and Papers of which this is the twelfth edition. The collections have contributed to many notable publications, television documentaries, school textbooks and academic works. They not only hold value as research tools, teaching aids and as crucial evidence for the intellectual development of theories and models but they contain collective social memory. Consequently, Historical Papers is an accessible hub for human rights research serving civil society as well as scholars. The first three editions of the Guide were arranged alphabetically. -

Grazing the Modern World: Merino Sheep in South Africa and the United States, 1775-1840

GRAZING THE MODERN WORLD: MERINO SHEEP IN SOUTH AFRICA AND THE UNITED STATES, 1775-1840. by Benjamin Hurwitz A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy History Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Department Chairperson ___________________________________________ Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Summer Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Grazing the Modern World: Merino Sheep in South Africa and the United States, 1775- 1840. A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University by Benjamin Hurwitz Master of Arts College of William and Mary in Virginia Bachelor of Arts College of William and Mary in Virginia Director: Benedict Carton, Robert T. Hawkes Professor Department of History Summer Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright 2017 Benjamin Hurwitz All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people who deserve my thanks for their help in the completion of this project. I will begin by thanking my supervisor, Dr. Benedict Carton for his relentless enthusiasm and engagement from the very beginning of this project, for always asking difficult questions and pushing for confident responses. Dr. Rosemarie Zagarri and Dr. Jane Hooper made this dissertation infinitely stronger by helping to situate this story within the Atlantic and Indian Ocean Worlds. Their commitment and encouragement provided me with great comfort throughout this process. Stephen Kane read many drafts of this work and lent many hours of conversation to discussing it. -

July/August 2013

c1-c4CAMja13_c1-c1CAMMA05 6/13/13 1:00 PM Page c1 July | August 2013 $6.00 Alumni Magazine CorneOWNED AND PUBLISHED BY THE CORNELL ALUMNI ASSOCIATION Glass Menagerie Film project brings sea creatures to life Inside: CU joins MOOC movement A doctor at the Boston Marathon cornellalumnimagazine.com c1-c4CAMja13_c1-c1CAMMA05 6/13/13 1:00 PM Page c2 c1-c4CAMja13_c1-c1CAMMA05 6/13/13 1:00 PM Page 1 02-03CAMja13toc_000-000CAMJF07currents 6/18/13 3:03 PM Page 2 July/August 2013 Volume 116 Number 1 In This Issue Corne Alumni Magazine 4 From David Skorton Regaining our faculties 6 The Big Picture Reunion 2013 8 Correspondence A wish for 2015 12 From the Hill The graduates 16 Sports Nation’s best laxer 20 Authors Playing by heart 96 32 22 Big Red Writers 40 Wines of the Finger Lakes 42 Forward Into the Past Silver Thread 2012 Dry Riesling JIM ROBERTS ’71 56 Classifieds & Cornellians in Business America has gone mad for MOOCs—the “massive open online courses” that prom- ise to bring higher education to all, regardless of finances or geography. This spring, 57 Alma Matters Cornell announced that it was jumping into the MOOC movement, joining a nonprofit founded by Harvard and MIT to create four initial courses. Despite the 60 Class Notes potential benefits, though, some on campus and elsewhere are wary—seeing 92 Alumni Deaths MOOCs as a possible threat to academic quality and professorial careers. CAM speaks to the architects of Cornell’s foray, offering MOOCs 101. 96 Cornelliana Fashion mavens Legacies 46 Beyond the Sea To see the list of under- graduate legacies who BETH SAULNIER Currents entered in fall 2012, go to cornellalumnimagazine.com Photographer David Brown ’83 was working at the Johnson Museum when he came across a collection of undersea creatures made entirely of glass. -

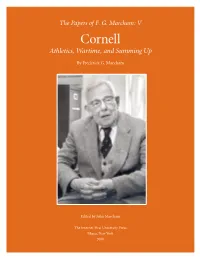

Athletics, Wartime, and Summing Up

The Papers of F. G. Marcham: V Cornell Athletics, Wartime, and Summing Up By Frederick G. Marcham Edited by John Marcham The Internet-First University Press Ithaca, New York 2006 The Papers of F. G. Marcham: V Cornell Athletics, Wartime, and Summing Up By Frederick G. Marcham Edited by John Marcham The Internet-First University Press Ithaca, New York 2006 The Internet-First University Press Ithaca NY 14853 Copyright © 2006 by John Marcham Cover: Professor Marcham in his office in McGraw Hall, March 4, 1987, in his 63rd year of teaching at Cornell University. —Charles Harrington, University Photos. For permission to quote or otherwise reproduce from this volume, write John Marcham, 414 E. Buffalo St., Ithaca, N.Y., U.S.A. (607) 273-5754. My successor handling this copyright will be my daughter Sarah Marcham, 131 Upper Creek Rd., Freeville, N.Y. 13068 (607) 347-6633. Printed in the United States of America ii Cornell: Athletics, Wartime, and Summing Up by Frederick G. Marcham Contents Associations with Athletics, 1923-61 At Christ’s Hospital ............................................................1 In the Army and a Bad Heart ............................................3 Rehabilitation and Oxford .................................................3 On to the U.S.A. and Cornell ............................................6 Golf and Other Sports ........................................................7 The Politics of Athletics .....................................................8 Back to Boxing ....................................................................9 -

Rochester Review? Alan B

Rochester Letters Review University of Rochester Winter 1986-87 The Review welcomes letters from readers and will use above such petty considerations as the sex or G.S.M.'s New Identity 2 as many ofthem as space permits. Letters may be race ofthe caretaker. Eliminating discrimination Now It's the Simon School edited for brevity and clarity. in this realm is just one more step in the direc tion of eliminating discrimination in general. The Other Side of the Window 5 Thanks, Jim, and "Jess," wherever you are! Radio station WRUR Joan Goodman Ganz '73 Albany The School at Society Corner 10 Congratulations on your compelling, sensi Teaching in the segregated South tive - yes, magnificent photograph - on the When Pain Does Not Sleep 15 cover of the Fall 1986 Rochester Review. The pho New treatments for chronic pain tograph exudes compassion and tenderness as well as bringing to focus what Tolstoy believed The First Hundred Years 18 to be the keystone of Christianity- the brother Centenarian George Abbott '11 hood ofman. A medal should be pinned on the photogra Departments pher for one of the most remarkable photo graphs of my lifetime. Rochester in Review 22 Jack Grossfield '31 Alumni Gazette 30 Silver Spring, Maryland Alumnotes 32 A medal has been duly affixed to the shirtfront ofJeJf DR Where You Are 44 Goldberg, Rochester Review staffphotographer We liked the photo, too - Editor. In Memoriam 46 Tourette's Alumni Travel 47 I found it a heartening coincidence that I Jim Murphy and friends Review Point 48 received my Rochester Review [Fall 1986], con taining the article on Tourette's Syndrome, the Jim Murphy, RN same day "St. -

PATHWAYS to UNDERSTANDING WHITE POVERTY in SOUTH AFRICA 1902 to 1948

PATHWAYS TO UNDERSTANDING WHITE POVERTY IN SOUTH AFRICA 1902 to 1948 Dr John Richard Cowlin Thesis presented in the fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Faculty of Humanities / History Supervisor: Prof. Albert Grundlingh December , 2018 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Copyright © 2018 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za 2 Abstract This thesis examines the social and economic circumstances of descendants of mainly Dutch settlers who became known as the poor whites during the early part of the 20th century. Attention is given to particular aspects of rural pastoral society such as farming methods, education, land usage and demographics. A brief sketch of the South African economy prior to the mineral revolution has been included in order to understand the impact on the poor white of the discovery of diamonds and gold which became a trigger for future industrialisation. The widespread failure of their subsistence pastoral economy led to significant urbanisation mainly on the Witwatersrand. The concerns of the Dutch Reformed Church and later Afrikaner politicians for a solution to the poor white problem led to the establishment of the Carnegie Commission, funded mainly by the Carnegie Corporation of New York. -

The Power Of

The Power of Professorships With its original goal for endowed professorships already met, The Meliora Challenge sets a new target: establishing 100 such positions for Rochester faculty by 2016. By Scott Hauser The Meliora Challenge has marked a Endowed positions also help retain and at- milestone moment: the $1.2 billion compre- tract talented faculty members who are leaders hensive campaign this spring reached its goal of in their fields, schools, and the local community, establishing 80 endowed professorships. as well as provide critical funds to support With two years to go, the target has research. been increased to 100 endowed posi- G enerous support from alumni, tions by the time the Campaign is faculty, and friends of the Univer- scheduled to end in June 2016. sity has driven the early success “This is a milestone achieve- of the endowed professorship ment to be celebrated,” Presi- initiative, prompting the new dent Joel Seligman said. “It is target. safe to say that just as great Reaching the new goal cathedrals are built brick would nearly double the by brick, great universities number of endowed profes- are built professorship by sorships at the University, professorship. which counted a total of 107 “The work of our faculty is such faculty positions when among the most enduring as- the Campaign first got under pects of our University, and our way in 2005. alumni and friends who support Ceremonies to recognize inau- their work by endowing professor- gural appointees and the supporters ships deserve our recognition and thanks.” of each new position began in 2006. -

University of Rochester

Letters Rochester Review SEpTEmbER–OctobER 2014 VOLUmE 77, NO. 1 Editor Scott Hauser Associate Editors Karen McCally ’02 (PhD) Kathleen McGarvey Contributors Valerie Alhart, David Barnstone, Adam Fenster, Rachel Goldstein, Susan Hagen, Peter Iglinski, Megan Mack, Melissa Lang, Sara Miller, Dennis O’Donnell, Leslie Orr, Leonor Sierra, and Brandon Vick Editorial Office 22 Wallis Hall University of Rochester Box 270044, Rochester, NY 14627-0044 (585) 275-4121 Fax: (585) 275-0359 mODEL CAmpUS: Former University president Cornelis de Kiewiet holds a model of a E-mail: [email protected] proposed men’s dining center, a project that was eventually built near Rush Rhees Library. www.rochester.edu/pr/Review Address Changes Kudos for Cornelis? center was built and later renamed as to- 300 East River Road I really enjoyed the July-August issue, es- day’s Douglass Dining Center, still feeding Box 270032 pecially the profile of Cornelis de Kiewiet students—men and women—and located Rochester, NY 14627-0032 (“A Dynamic Attitude”). I had no idea he between Rush Rhees Library and what’s (585) 275-8602; toll free: (866) 673-0181 Email: [email protected] was responsible for so much of the Uni- now the Goergen Athletic Center. —Scott https://alumniportal.ur.rochester.edu versity that I attended in the early 1970s. Hauser, Editor. Moving the women’s college to the River Design Campus and hiring Richard Fenno, one of ‘I Was There’ Steve Boerner Typography & Design Inc. my favorite professors, were two initiatives Congratulations once more on a colorful Published six times a year for alumni, I particularly appreciated! and interesting issue of Review.