Solar and Sidereal Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ast 443 / Phy 517

AST 443 / PHY 517 Astronomical Observing Techniques Prof. F.M. Walter I. The Basics The 3 basic measurements: • WHERE something is • WHEN something happened • HOW BRIGHT something is Since this is science, let’s be quantitative! Where • Positions: – 2-dimensional projections on celestial sphere (q,f) • q,f are angular measures: radians, or degrees, minutes, arcsec – 3-dimensional position in space (x,y,z) or (q, f, r). • (x,y,z) are linear positions within a right-handed rectilinear coordinate system. • R is a distance (spherical coordinates) • Galactic positions are sometimes presented in cylindrical coordinates, of galactocentric radius, height above the galactic plane, and azimuth. Angles There are • 360 degrees (o) in a circle • 60 minutes of arc (‘) in a degree (arcmin) • 60 seconds of arc (“) in an arcmin There are • 24 hours (h) along the equator • 60 minutes of time (m) per hour • 60 seconds of time (s) per minute • 1 second of time = 15”/cos(latitude) Coordinate Systems "What good are Mercator's North Poles and Equators Tropics, Zones, and Meridian Lines?" So the Bellman would cry, and the crew would reply "They are merely conventional signs" L. Carroll -- The Hunting of the Snark • Equatorial (celestial): based on terrestrial longitude & latitude • Ecliptic: based on the Earth’s orbit • Altitude-Azimuth (alt-az): local • Galactic: based on MilKy Way • Supergalactic: based on supergalactic plane Reference points Celestial coordinates (Right Ascension α, Declination δ) • δ = 0: projection oF terrestrial equator • (α, δ) = (0,0): -

A Study of Ancient Khmer Ephemerides

A study of ancient Khmer ephemerides François Vernotte∗ and Satyanad Kichenassamy** November 5, 2018 Abstract – We study ancient Khmer ephemerides described in 1910 by the French engineer Faraut, in order to determine whether they rely on observations carried out in Cambodia. These ephemerides were found to be of Indian origin and have been adapted for another longitude, most likely in Burma. A method for estimating the date and place where the ephemerides were developed or adapted is described and applied. 1 Introduction Our colleague Prof. Olivier de Bernon, from the École Française d’Extrême Orient in Paris, pointed out to us the need to understand astronomical systems in Cambo- dia, as he surmised that astronomical and mathematical ideas from India may have developed there in unexpected ways.1 A proper discussion of this problem requires an interdisciplinary approach where history, philology and archeology must be sup- plemented, as we shall see, by an understanding of the evolution of Astronomy and Mathematics up to modern times. This line of thought meets other recent lines of research, on the conceptual evolution of Mathematics, and on the definition and measurement of time, the latter being the main motivation of Indian Astronomy. In 1910 [1], the French engineer Félix Gaspard Faraut (1846–1911) described with great care the method of computing ephemerides in Cambodia used by the horas, i.e., the Khmer astronomers/astrologers.2 The names for the astronomical luminaries as well as the astronomical quantities [1] clearly show the Indian origin ∗F. Vernotte is with UTINAM, Observatory THETA of Franche Comté-Bourgogne, University of Franche Comté/UBFC/CNRS, 41 bis avenue de l’observatoire - B.P. -

Geological Timeline

Geological Timeline In this pack you will find information and activities to help your class grasp the concept of geological time, just how old our planet is, and just how young we, as a species, are. Planet Earth is 4,600 million years old. We all know this is very old indeed, but big numbers like this are always difficult to get your head around. The activities in this pack will help your class to make visual representations of the age of the Earth to help them get to grips with the timescales involved. Important EvEnts In thE Earth’s hIstory 4600 mya (million years ago) – Planet Earth formed. Dust left over from the birth of the sun clumped together to form planet Earth. The other planets in our solar system were also formed in this way at about the same time. 4500 mya – Earth’s core and crust formed. Dense metals sank to the centre of the Earth and formed the core, while the outside layer cooled and solidified to form the Earth’s crust. 4400 mya – The Earth’s first oceans formed. Water vapour was released into the Earth’s atmosphere by volcanism. It then cooled, fell back down as rain, and formed the Earth’s first oceans. Some water may also have been brought to Earth by comets and asteroids. 3850 mya – The first life appeared on Earth. It was very simple single-celled organisms. Exactly how life first arose is a mystery. 1500 mya – Oxygen began to accumulate in the Earth’s atmosphere. Oxygen is made by cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) as a product of photosynthesis. -

Captain Vancouver, Longitude Errors, 1792

Context: Captain Vancouver, longitude errors, 1792 Citation: Doe N.A., Captain Vancouver’s longitudes, 1792, Journal of Navigation, 48(3), pp.374-5, September 1995. Copyright restrictions: Please refer to Journal of Navigation for reproduction permission. Errors and omissions: None. Later references: None. Date posted: September 28, 2008. Author: Nick Doe, 1787 El Verano Drive, Gabriola, BC, Canada V0R 1X6 Phone: 250-247-7858, FAX: 250-247-7859 E-mail: [email protected] Captain Vancouver's Longitudes – 1792 Nicholas A. Doe (White Rock, B.C., Canada) 1. Introduction. Captain George Vancouver's survey of the North Pacific coast of America has been characterized as being among the most distinguished work of its kind ever done. For three summers, he and his men worked from dawn to dusk, exploring the many inlets of the coastal mountains, any one of which, according to the theoretical geographers of the time, might have provided a long-sought-for passage to the Atlantic Ocean. Vancouver returned to England in poor health,1 but with the help of his brother John, he managed to complete his charts and most of the book describing his voyage before he died in 1798.2 He was not popular with the British Establishment, and after his death, all of his notes and personal papers were lost, as were the logs and journals of several of his officers. Vancouver's voyage came at an interesting time of transition in the technology for determining longitude at sea.3 Even though he had died sixteen years earlier, John Harrison's long struggle to convince the Board of Longitude that marine chronometers were the answer was not quite over. -

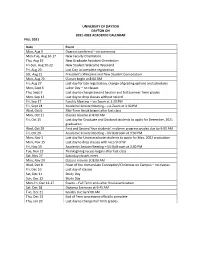

2021-2022.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON DAYTON OH 2021-2022 ACADEMIC CALENDAR FALL 2021 Date Event Mon, Aug 9 Degrees conferred – no ceremony Mon-Tue, Aug 16-17 New Faculty Orientation Thu, Aug 19 New Graduate Assistant Orientation Fri-Sun, Aug 20-22 New Student Welcome Weekend Fri, Aug 20 Last Day to complete registration Sat, Aug 21 President’s Welcome and New Student Convocation Mon, Aug 23 Classes begin at 8:00 AM Fri, Aug 27 Last day for late registration, change of grading options and schedules Mon, Sept 6 Labor Day – no classes Thu, Sept 9 Last day to change Second Session and full Summer Term grades Mon, Sep 13 Last day to drop classes without record Fri, Sep 17 Faculty Meeting – via Zoom at 3:30 PM Fri, Sept 24 Academic Senate Meeting – via Zoom at 3:30 PM Wed, Oct 6 Mid-Term Break begins after last class Mon, Oct 11 Classes resume at 8:00 AM Fri, Oct 15 Last day for Graduate and Doctoral students to apply for December, 2021 graduation Wed, Oct 20 First and Second Year students’ midterm progress grades due by 9:00 AM Fri, Oct 29 Academic Senate Meeting – KU Ballroom at 3:30 PM Mon, Nov 1 Last day for Undergraduate students to apply for May, 2022 graduation Mon, Nov 15 Last day to drop classes with record of W Fri, Nov 19 Academic Senate Meeting – KU Ballroom at 3:30 PM Tue, Nov 23 Thanksgiving recess begins after last class Sat, Nov 27 Saturday classes meet Mon, Nov 29 Classes resume at 8:00 AM Wed, Dec 8 Feast of the Immaculate Conception/Christmas on Campus – no classes Fri, Dec 10 Last day of classes Sat, Dec 11 Study Day Sun, Dec 12 Study Day Mon-Fri, Dec 13-17 Exams – Fall Term ends after final examination Sat, Dec 18 Diploma Exercises at 9:45 AM Tue, Dec 21 Grades due by 9:00 AM Thu, Dec 23 End of Term processing officially complete Thu, Jan 20 Last day to change Fall Term grades CHRISTMAS BREAK Date Event Sun, Dec 19 Christmas Break begins Sun, Jan 9 Christmas Break ends SPRING 2022 Date Event Fri, Jan 7 Last day to complete registration Mon, Jan 10 Classes begin at 8:00 AM. -

Hourglass User and Installation Guide About This Manual

HourGlass Usage and Installation Guide Version7Release1 GC27-4557-00 Note Before using this information and the product it supports, be sure to read the general information under “Notices” on page 103. First Edition (December 2013) This edition applies to Version 7 Release 1 Mod 0 of IBM® HourGlass (program number 5655-U59) and to all subsequent releases and modifications until otherwise indicated in new editions. Order publications through your IBM representative or the IBM branch office serving your locality. Publications are not stocked at the address given below. IBM welcomes your comments. For information on how to send comments, see “How to send your comments to IBM” on page vii. © Copyright IBM Corporation 1992, 2013. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents About this manual ..........v Using the CICS Audit Trail Facility ......34 Organization ..............v Using HourGlass with IMS message regions . 34 Summary of amendments for Version 7.1 .....v HourGlass IOPCB Support ........34 Running the HourGlass IMS IVP ......35 How to send your comments to IBM . vii Using HourGlass with DB2 applications .....36 Using HourGlass with the STCK instruction . 36 If you have a technical problem .......vii Method 1 (re-assemble) .........37 Method 2 (patch load module) .......37 Chapter 1. Introduction ........1 Using the HourGlass Audit Trail Facility ....37 Setting the date and time values ........3 Understanding HourGlass precedence rules . 38 Introducing -

Survey of Microbial Composition And

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 7 Article 11 2013 Survey of Microbial Composition and Mechanisms of Living Stromatolites of the Bahamas and Australia: Developing Criteria to Determine the Biogenicity of Fossil Stromatolites Georgia Purdom Answers in Genesis Andrew A. Snelling Answers in Genesis Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Purdom, Georgia and Snelling, Andrew A. (2013) "Survey of Microbial Composition and Mechanisms of Living Stromatolites of the Bahamas and Australia: Developing Criteria to Determine the Biogenicity of Fossil Stromatolites," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 7 , Article 11. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol7/iss1/11 Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Creationism. Pittsburgh, PA: Creation Science Fellowship SURVEY OF MICROBIAL COMPOSITION AND MECHANISMS OF LIVING STROMATOLITES OF THE BAHAMAS AND AUSTRALIA: DEVELOPING CRITERIA TO DETERMINE THE BIOGENICITY OF FOSSIL STROMATOLITES Georgia Purdom, PhD, Answers in Genesis, P.O. Box 510, Hebron, KY, 41048 Andrew A. -

“The Hourglass”

Grand Lodge of Wisconsin – Masonic Study Series Volume 2, issue 5 November 2016 “The Hourglass” Lodge Presentation: The following short article is written with the intention to be read within an open Lodge, or in fellowship, to all the members in attendance. This article is appropriate to be presented to all Master Masons . Master Masons should be invited to attend the meeting where this is presented. Following this article is a list of discussion questions which should be presented following the presentation of the article. The Hourglass “Dost thou love life? Then squander not time, for that is the stuff that life is made of.” – Ben Franklin “The hourglass is an emblem of human life. Behold! How swiftly the sands run, and how rapidly our lives are drawing to a close.” The hourglass works on the same principle as the clepsydra, or “water clock”, which has been around since 1500 AD. There are the two vessels, and in the case of the clepsydra, there was a certain amount of water that flowed at a specific rate from the top to bottom. According to the Guiness book of records, the first hourglass, or sand clock, is said to have been invented by a French monk called Liutprand in the 8th century AD. Water clocks and pendulum clocks couldn’t be used on ships because they needed to be steady to work accurately. Sand clocks, or “hour glasses” could be suspended from a rope or string and would not be as affected by the moving ship. For this reason, “sand clocks” were in fairly high demand in the shipping industry back in the day. -

C++ DATE and TIME Rialspo Int.Co M/Cplusplus/Cpp Date Time.Htm Copyrig Ht © Tutorialspoint.Com

C++ DATE AND TIME http://www.tuto rialspo int.co m/cplusplus/cpp_date_time.htm Copyrig ht © tutorialspoint.com The C++ standard library does not provide a proper date type. C++ inherits the structs and functions for date and time manipulation from C. To access date and time related functions and structures, you would need to include <ctime> header file in your C++ prog ram. There are four time-related types: clock_t, time_t, size_t, and tm. The types clock_t, size_t and time_t are capable of representing the system time and date as some sort of integ er. The structure type tm holds the date and time in the form of a C structure having the following elements: struct tm { int tm_sec; // seconds of minutes from 0 to 61 int tm_min; // minutes of hour from 0 to 59 int tm_hour; // hours of day from 0 to 24 int tm_mday; // day of month from 1 to 31 int tm_mon; // month of year from 0 to 11 int tm_year; // year since 1900 int tm_wday; // days since sunday int tm_yday; // days since January 1st int tm_isdst; // hours of daylight savings time } Following are the important functions, which we use while working with date and time in C or C++. All these functions are part of standard C and C++ library and you can check their detail using reference to C++ standard library g iven below. SN Function & Purpose 1 time_t time(time_t *time); This returns the current calendar time of the system in number of seconds elapsed since January 1, 1970. If the system has no time, .1 is returned. -

Capricious Suntime

[Physics in daily life] I L.J.F. (Jo) Hermans - Leiden University, e Netherlands - [email protected] - DOI: 10.1051/epn/2011202 Capricious suntime t what time of the day does the sun reach its is that the solar time will gradually deviate from the time highest point, or culmination point, when on our watch. We expect this‘eccentricity effect’ to show a its position is exactly in the South? e ans - sine-like behaviour with a period of a year. A wer to this question is not so trivial. For ere is a second, even more important complication. It is one thing, it depends on our location within our time due to the fact that the rotational axis of the earth is not zone. For Berlin, which is near the Eastern end of the perpendicular to the ecliptic, but is tilted by about 23.5 Central European time zone, it may happen around degrees. is is, aer all, the cause of our seasons. To noon, whereas in Paris it may be close to 1 p.m. (we understand this ‘tilt effect’ we must realise that what mat - ignore the daylight saving ters for the deviation in time time which adds an extra is the variation of the sun’s hour in the summer). horizontal motion against But even for a fixed loca - the stellar background tion, the time at which the during the year. In mid- sun reaches its culmination summer and mid-winter, point varies throughout the when the sun reaches its year in a surprising way. -

The Milesian Calendar in Short

The Milesian calendar in short Quick description The Milesian calendar is a solar calendar, with weighted months, in phase with seasons. It enables you to understand and take control of the Earth’s time. The next picture represents the Milesian calendar with the mean solstices and equinoxes. Leap days The leap day is the last day of the year, it is 31 12m or 12m 31 (whether you use British or American English). This day comes just before a leap year. Years The Milesian years are numbered as the Gregorian ones. However, they begin 10 or 11 days earlier. 1 Firstem Y (1 1m Y) corresponds to 21 December Y-1 when Y is a common year, like 2019. But it falls on 22 December Y-1 when Y is a leap year like 2020. The mapping between Milesian and Gregorian dates is shifted by one for 71 days during “leap winters”, i.e. from 31 Twelfthem to 9 Thirdem. 10 Thirdem always falls on 1 March, and each following Milesian date always falls on a same Gregorian date. Miletus S.A.R.L. – 32 avenue Théophile Gautier – 75016 Paris RCS Paris 750 073 041 – Siret 750 073 041 00014 – APE 7022Z Date conversion with the Gregorian calendar The first day of a Milesian month generally falls on 22 of the preceding Gregorian month, e.g.: 1 Fourthem (1 4m) falls on 22 March, 1 Fifthem (1 5m) on 22 April etc. However: • 1 Tenthem (1 10m) falls on 21 September; • 1 12m falls on 21 November; • 1 1m of year Y falls on 21 December Y-1 if Y is a common year, but on 22 December if Y is a leap year; • 1 2m and 1 3m falls on 21 January and 21 February in leap years, 20 January and 20 February in common years. -

Calendrical Calculations: Third Edition

Notes and Errata for Calendrical Calculations: Third Edition Nachum Dershowitz and Edward M. Reingold Cambridge University Press, 2008 4:00am, July 24, 2013 Do I contradict myself ? Very well then I contradict myself. (I am large, I contain multitudes.) —Walt Whitman: Song of Myself All those complaints that they mutter about. are on account of many places I have corrected. The Creator knows that in most cases I was misled by following. others whom I will spare the embarrassment of mention. But even were I at fault, I do not claim that I reached my ultimate perfection from the outset, nor that I never erred. Just the opposite, I always retract anything the contrary of which becomes clear to me, whether in my writings or my nature. —Maimonides: Letter to his student Joseph ben Yehuda (circa 1190), Iggerot HaRambam, I. Shilat, Maaliyot, Maaleh Adumim, 1987, volume 1, page 295 [in Judeo-Arabic] Cuiusvis hominis est errare; nullius nisi insipientis in errore perseverare. [Any man can make a mistake; only a fool keeps making the same one.] —Attributed to Marcus Tullius Cicero If you find errors not given below or can suggest improvements to the book, please send us the details (email to [email protected] or hard copy to Edward M. Reingold, Department of Computer Science, Illinois Institute of Technology, 10 West 31st Street, Suite 236, Chicago, IL 60616-3729 U.S.A.). If you have occasion to refer to errors below in corresponding with the authors, please refer to the item by page and line numbers in the book, not by item number.