Swimming from the Island of the Colorblind: Deserting an Ill- Conceived Constitutional Metaphor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture 9: Population Genetics

Lecture 9: Population Genetics Plan of the lecture I. Population Genetics: definitions II. Hardy-Weinberg Law. III. Factors affecting gene frequency in a population. Small populations and founder effect. IV. Rare Alleles and Eugenics The goal of this lecture is to make students familiar with basic models of population genetics and to acquaint students with empirical tests of these models. It will discuss the primary forces and processes involved in shaping genetic variation in natural populations (mutation, drift, selection, migration, recombination, mating patterns, population size and population subdivision). I. Population genetics: definitions Population – group of interbreeding individuals of the same species that are occupying a given area at a given time. Population genetics is the study of the allele frequency distribution and change under the influence of the 4 evolutionary forces: natural selection, mutation, migration (gene flow), and genetic drift. Population genetics is concerned with gene and genotype frequencies, the factors that tend to keep them constant, and the factors that tend to change them in populations. All the genes at all loci in every member of an interbreeding population form gene pool. Each gene in the genetic pool is present in two (or more) forms – alleles. Individuals of a population have same number and kinds of genes (except sex genes) and they have different combinations of alleles (phenotypic variation). The applications of Mendelian genetics, chromosomal abnormalities, and multifactorial inheritance to medical practice are quite evident. Physicians work mostly with patients and families. However, as important as they may be, genes affect populations, and in the long run their effects in populations have a far more important impact on medicine than the relatively few families each physician may serve. -

FEDERATED STATES of MICRONESIA: Preliminary Damage Assessment

FEDERATED STATES OF MICRONEISA: Preliminary Damage Assessment (PDA) High Tide Event, December 7-12, 2008 Report Submitted By Marilyn Shigetani PDA Team Leader (1/26/2009) 1 1. Background: I. Precipitators According to the National Weather Service, in early December 2008 a vigorous low pressure system formed north of Wake Island. Surface reports indicated a large area of 50 to 60kt surface winds formed along the low pressure’s northern periphery while it moved slowly towards the southeast to near 20N 174E by Sunday December 7, 2008. Surface winds weakened slightly, but remained at gale force, 35-40kt, by Tuesday, December 9, 2008. At the same time the moon’s orbit with the earth was approaching its closest point (perigee) causing unusually high tides. Reports from Altimetry showed significant wave heights in excess of 30ft near the low pressure system generating northerly swells in the range of 12-15ft from Majuro westward to Pohnpei and Chuuk. The combination of these factors resulted in high wave and tide events throughout the FSM. II. Evolution of PDA Request Beginning on December 7, 2008 and concluding on December 12, 2008, a tidal event swept over the Federated States of Micronesia, causing damage to crops and coastal areas throughout the country. In response to this incident the Governor of Pohnpei State, John Ehsa, declared the islands of Kapingamarangi, Mwokil, Ngetik, Nukuror, Oroluk, Pakin and Pingelap to be in State of Emergency on December 19, 2008. On December 24, 2008, Governor Robert Weilbacher of the State of Kosrae declared the existence of a state of emergency because of tidal surges that caused property flooding, damage and destruction of households, businesses, infrastructure and crops. -

Checklist and Bibliography of the Marine Benthic Algae Within Chuuk, Pohnpei, and Kosrae States, Federated States of Micronesia

Checklist and Bibliography of the Marine Benthic Algae Within Chuuk, Pohnpei, and Kosrae States, Federated States of Micronesia Roy T. Tsuda Pacific Biological Survey Bishop Museum January 2006 Checklist and Bibliography of the Marine Benthic Algae Within Chuuk, Pohnpei, and Kosrae States, Federated States of Micronesia Prepared for: Marine Introduced Species Workshop in Chuuk, Pohnpei, and Kosrae States, Federated States of Micronesia Roy T. Tsuda Department of Natural Sciences Bishop Museum Bishop Museum Pacific Biological Survey Bishop Museum Technical Report No. 34 Honolulu, Hawai‘i January 2006 2 Published by Bishop Museum Press 1525 Bernice Street Honolulu, Hawai‘i Copyright © 2006 Bishop Museum All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America LOGO ISSN 1085-455X Contribution No. 2006-001 to the Pacific Biological Survey 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 6 SPECIES AND REFERENCES 8 Division Cyanophyta 8 Class Cyanophyceae 8 Order Chroococcales 8 Family Entophysalidaceae Family Microcystaceae Order Oscillatoriales 8 Family Oscillatoriaceae Family Phormidiaceae Family Pseudanabaenaceae Family Schizothrichaceae Order Nostocales 10 Family Nostocaceae Family Rivulariaceae Family Scytonemataceae Order Stigonematales 10 Family Nostochopsidaceae Division Chlorophyta 11 Class Chlorophyceae 11 Order Ulotrichales 11 Family Ulotrichaceae Order Ctenocladales 11 Family Ulvellaceae Order Ulvales 11 Family Ulvaceae Order Cladophorales 11 Family Anadyomenaceae Family Cladophoraceae Family Siphonocladaceae Family Valoniaceae 4 Page Order -

Federated States of Micronesia SBSAP

Pohnpei State Biodiversity Strategic Action Plan September 2004 r-- Table of contents Acknowledgements 2 Acronyms 4 Introduction 5 Map of Pohnpei State (with Areas of Biodiversity Significance) .9 Mission, Vision, Strategic Goals and Actions 10 Monitoring and Evaluation . 18 Implementation .19 Financing .19 Signatures (state and municipal leaders) 21 Acknowledgements This Action (Implementation) Plan, together with the FSM National Strategic Action Plan (NBSAP), provides the framework for biodiversity conservation, resource, waste, pollution and energy management in Pohnpei State for the next five years and beyond. The plan is the result of numerous consultations over two years with input from national, state, local and resource agency/organization leaders and community representatives. This Plan includes the most relevant strategies goals and actions for Pohnpei State's priority areas in biodiversity conservation. resource. waste, pollution and energy management. The people listed below deserve special recognition for their exceptional dedication and contributions to this plan. With their exceptional knowledge and vast experience in the areas, we feel that this plan contains the state's highest priority and most relevant strategic goals and actions. Finally, this plan and the extensive efforts that went into its development were made possible by the generous financial support of the Global Environment Facility (GEF) through the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Lt. Governor Jack E. Yakana Chairman, Pohnpei Resource Management Committee (PRMC) Consultant K_ostka, CSP Executive Director Advisory Team Jack E. Vakana, Pohnpei State Lt. Governor Youser Anson, DL&R Director Herson Anson, DL&R — DF Chief Bill Raynor, TNC Micronesia Program Director !limbers Adelino Lorens, SOEA DA Chief Kcnio Frank, Sapvvuahfik Chief Representative Ausen T. -

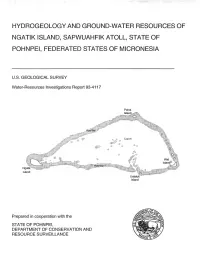

Hydrogeology and Ground-Water Resources of Ngatik Island, Sapwuahfik Atoll, State of Pohnpei, Federated States of Micronesia

HYDROGEOLOGY AND GROUND-WATER RESOURCES OF NGATIK ISLAND, SAPWUAHFIK ATOLL, STATE OF POHNPEI, FEDERATED STATES OF MICRONESIA U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Water-Resources Investigations Report 93-4117 Peina Ngatik Island Uataluk Island Prepared in cooperation with the STATE OF POHNPEI, DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND RESOURCE SURVEILLANCE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Gordon P. Eaton, Director Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government For sale by the U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services Box 25286 Denver, CO 80225-0286 For additional information write to: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey 677 Ala Moana Blvd., Suite 415 Honolulu, HI 96813 CONTENTS Abstract ..................................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................................. 1 Purpose and Scope ...................................................................... 1 Background ........................................................................... 3 Previous Investigations .................................................................. 4 Acknowledgments ...................................................................... 4 Methods of Study ............................................................................. 4 Installation of Driven-Well Network ....................................................... -

Food Security in Small Islands: Case Studies in the Federated States of Micronesia

Food Security in Small Islands: Case Studies in the Federated States of Micronesia 著者 "YAMAMOTO Sota" journal or 南太平洋海域調査研究報告=Occasional papers publication title volume 54 page range 27-33 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10232/24701 2 南太平洋海域調査研究報告 No.54(2014年12月) OCCASIONAL PAPERS No.54(December 2014) Food Security in Small Islands: Case Studies in the Federated States of Micronesia YAMAMOTO Sota Research Center for the Pacific Islands, Kagoshima University Abstract In the 1950s, people in the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) still ate a “traditional” diet based on starchy staple crops and marine resources, but this began to be replaced by imported food such as rice, flour, sugar, fatty foods, and other processed foods after the United States Department of Agriculture started its supplementary feeding program in the 1960s. This phenomenon accelerated after a Compact of Free Association was signed between the FSM and the United States in 1986. Since then, the FSM has faced serious public health problems due to this new diet and other lifestyle changes. On small islands and atolls, imported foods and medicines may not arrive for more than a month if a typhoon or an oil crisis occurs. In this study, a detailed study of household food consumption is shown to represent the present situation of food security on Piis-Paneu Island (Chuuk Atoll, Chuuk State) and Pingelap Island (Pohnpei State). Keywords: banana, breadfruit, canned fish and meat, ethnobotany, MIRAB, root and tuber crops (Alocasia, Colocasia, Cyrtosperma, Xanthosoma, etc.) Introduction The Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) consists of four states (Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei, and Kosrae, from west to east) composed of approximately 600 small islands, which amount to an area of approximately 700 km2. -

Major Fleet-Versus-Fleet Operations in the Pacific War, 1941–1945 Operations in the Pacific War, 1941–1945 Second Edition Milan Vego Milan Vego Second Ed

U.S. Naval War College U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons Historical Monographs Special Collections 2016 HM 22: Major Fleet-versus-Fleet Operations in the Pacific arW , 1941–1945 Milan Vego Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/usnwc-historical-monographs Recommended Citation Vego, Milan, "HM 22: Major Fleet-versus-Fleet Operations in the Pacific arW , 1941–1945" (2016). Historical Monographs. 22. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/usnwc-historical-monographs/22 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Monographs by an authorized administrator of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NAVAL WAR COLLEGE PRESS Major Fleet-versus-Fleet Major Fleet-versus-Fleet Operations in the Pacific War, 1941–1945 War, Pacific the in Operations Fleet-versus-Fleet Major Operations in the Pacific War, 1941–1945 Second Edition Milan Vego Milan Vego Milan Second Ed. Second Also by Milan Vego COVER Units of the 1st Marine Division in LVT Assault Craft Pass the Battleship USS North Carolina off Okinawa, 1 April 1945, by the prolific maritime artist John Hamilton (1919–93). Used courtesy of the Navy Art Collection, Washington, D.C.; the painting is currently on loan to the Naval War College Museum. In the inset image and title page, Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance ashore on Kwajalein in February 1944, immediately after the seizure of the island, with Admiral Chester W. -

Pingelapese Achromatopsia: Correlation Between Paradoxical Pupillary Response and Clinical Features G J Ben Simon, F a Abraham, S Melamed

223 SCIENTIFIC REPORT Br J Ophthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.2003.027284 on 21 January 2004. Downloaded from Pingelapese achromatopsia: correlation between paradoxical pupillary response and clinical features G J Ben Simon, F A Abraham, S Melamed ............................................................................................................................... Br J Ophthalmol 2004;88:223–225. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2003.027284 subunit of cone photoreceptor cGMP dependent cationic Aim: To evaluate the paradoxical pupillary constriction in channel, resulting in non-functioning cones. This mutation darkness in patients with Pingelapese achromatopsia (PA), differs from another gene for achromatopsia, mapped to and to describe a connection between this phenomenon and chromosome 2q11 (in an Iranian-Jewish population), where the clinical features. the a subunit of the cone photoreceptor cGMP dependent Methods: 27 patients with PA were examined. All underwent cationic channel is defective.11–14 a full ophthalmic examination which included Snellen visual A unique clinical feature of complete achromatopsia is acuity and ophthalmoscopy. Colour vision examination was paradoxical pupillary constriction to darkness. After exposure performed with Ishihara pseudoisochromatic plates and also to bright light for 2–3 minutes and transfer to darkness, with a colour plate consisting of five basic colours (red, many patients with achromatopsia (rod monochromatism) green, purple, yellow, and orange). Paradoxical pupillary will show pupillary constriction. This phenomenon (also response was examined and documented with a special know as Flynn phenomenon) is not unique to achromatopsia infrared video camera. Pupils’ images were analysed using and can be found in dominant optic atrophy, Leber’s the Scion Image program and the ratio of pupil size in congenital amaurosis, congenital stationary night blindness, darkness to its size in light was calculated and recorded. -

Health and Diet Among People Living in an Isolated Area: Case Study of Pingelap Island in Pohnpei State, the Federated States of Micronesia

Kobe University Repository : Kernel Health and Diet among People Living in an Isolated Area: Case Study タイトル of Pingelap Island in Pohnpei State, the Federated States of Title Micronesia 著者 Sakai, Moeno / Nakazawa, Minato / Abraham, Delpihn Author(s) 掲載誌・巻号・ページ International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Citation Health,17(21):7839 刊行日 2020-11 Issue date 資源タイプ Journal Article / 学術雑誌論文 Resource Type 版区分 publisher Resource Version © 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article 権利 is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of Rights the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). DOI 10.3390/ijerph17217839 JaLCDOI URL http://www.lib.kobe-u.ac.jp/handle_kernel/90007652 PDF issue: 2021-10-04 International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Health and Diet among People Living in an Isolated Area: Case Study of Pingelap Island in Pohnpei State, the Federated States of Micronesia Moeno Sakai 1,* , Minato Nakazawa 1 and Delpihn Abraham 2 1 Department of Public Health, Graduate School of Health Science, Kobe University, Kobe 654-0142, Japan; [email protected] 2 Department of Health and Social Affairs, Pohnpei State Department of Health Services, Kolonia, Pohnpei FM96941, Micronesia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 19 September 2020; Accepted: 9 October 2020; Published: 26 October 2020 Abstract: Pingelap Island in Pohnpei state is geographically isolated as the nearest island is 70 km away, and such geographical isolation is a challenge for public health due to the limited access to health services. -

Congress Okays Accord with Marshalls Inside

The Peace Unity Liberty AN OFFICIAL PUBLICATION FOR THE PEOPLE AND STATES OF THE FEDERATED STATES OF MICRONESIA JZo^ume II Kolonia, Pohnpei, April 15, 1987 Number 4 Congres^^^^ s okays accord with Marshalls KOLONIA, Pohnpei - The Fourth FSM Congress ratified an agreement with the Marshall Islands on dividing U.S. education transition funding un- der the Compact of Free Association, during its Fifth Special Session which was adjourned April 5, ahead of schedule. A 10-day session was called March 19 by President Tosiwo Nakayama to FOURTH CONGRESS IN FINAL SESSION - The Fourth FSM Congress is convening March consider a wide range of measures pend- 30 in Pohnpei its fifth and final special session before the next Congress is seated May 11. ing before his and the Fourth Congress From left, clockwise, are Senator Isaac Figir, Yap; Senator Elias Thomas, Pohnpei; Floor- terms end in May. It began March 30 Leader John Haglelgam, Yap; Page Adora Weital; Journal Clerk Sue Ann Schadeck; Speaker Bethwel Henry, Pohnpei; Chief Clerk Henry Asugar; the Rev. Rufus David; Page Rinda and was scheduled to continue through Siales; Vice Speaker Joab Sigrah, Kosrae; Senator Pedro Harris, Pohnpei; Senator Kalisto April 10. Refalopei, Truk; Senator Claude Phillip, Kosrae; Senator Tony Otto, Truk, and Senator Nick The Fifth Congress is scheduled to Bossy, Truk. convene May 1 1 its 30-day First Regu- lar Session. The Fourth Congress voted to over- President visits ride the veto March 5 by the President Mokil, Pingelap of an act to lower the interest ceiling from 12 to 5 per cent for FSM Dev- KOLONIA, Pohnpei - President Tos- elopment Bank Loans. -

International Human Rights Instruments

UNITED NATIONS HRI International Distr. GENERAL Human Rights HRI/CORE/1/Add.72 Instruments 13 June 1996 Original: ENGLISH CORE DOCUMENT FORMING PART OF THE REPORTS OF STATES PARTIES MICRONESIA [16 April 1996] I. PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY 1. The Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), along with the Republic of Palau, forms the Caroline Islands archipelago. One of the newly emerged Pacific island nations, FSM extends from the equator to 14 degrees north encompassing over 1 million square miles of ocean and a relatively small land area. Comprising the FSM are 607 high volcanic and low coral islands (atolls) only 65 of which are inhabited. The total land area is 270.8 square miles with an additional 2,776 square miles of lagoon areas. The four states of the FSM are, from east to west, the States of Kosrae, Pohnpei (formerly Ponape, renamed in November 1984), Chuuk (formerly Truk, renamed in January 1990) and Yap. 2. Kosrae is the easternmost State of the FSM. Kosrae is 5 degrees north of the equator and about 350 miles east-south-east of Pohnpei. It is a high volcanic island having 42 square miles of land, and it consists primarily of rugged mountainous slopes with only a very narrow coastal plain. Approximately 65 per cent of the island is in forest, 23 per cent in agroforest, 11 per cent in secondary vegetation with the remaining 3 per cent non-forest. 3. Pohnpei is a high volcanic island located 7 degrees north latitude and 158 degrees east longitude. Roughly circular and fringed by relatively dense mangrove forest, the distance across the island is approximately 15 miles. -

Long-Term Survey of Food Consumption on Pingelap Island, Pohnpei State, the Federated States of Micronesia

141 Long-Term Survey of Food Consumption on Pingelap Island, Pohnpei State, the Federated States of Micronesia YAMAMOTO Sota (Kagoshima University) Ⅰ Introduction Ⅱ Study Site and Data Collection Ⅲ Results and Discussion Ⅳ Conclusions Keywords: banana, breadfruit, Cyrtosperma merkusii, ethnobotany, imported food, remote island I Introduction The diets of developing countries are shifting rapidly, and overweight and obesity have emerged as major public health problems in some of these countries(Popkin and Gordon-Larsen, 2004). In 2016, the prevalence of obesity exceeded 20% in several Polynesian and Micronesian countries(NCD Risk Factor Collaboration, 2017), and the World Health Organization (WHO)(2018) reported that noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), including cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, account for an estimated 75% of all deaths in the Federated States of Micronesia(FSM). The FSM is composed of approximately 600 small islands lying just above the equator in the Western Pacific, and consists of four states(Yap, Chuuk, Pohnpei, and Kosrae; Fig. 1). Pohnpei State(population 36,196 as of the 2010 census; Government of the Federated States of Micronesia, 2014)consists of the main island, Pohnpei Island, and eight smaller outer islands, including Pingelap Atoll. Before the 1950s, the people of the FSM ate a traditional diet based on staple starchy crops and marine resources (Murai, 1954). After the United States Department of Agriculture started a supplementary feeding program in the 1960s, the traditional diet began to be replaced by a modern diet rich in rice, wheat flour, sugar, and other imported ― 15 ― 142 島嶼研究 第20 巻 2 号 or processed foods(Englberger et al., 2003). This change accelerated after a Compact of Free Association was signed between the FSM and the United States in 1986, guided by the Migration, Remittance, Aid, and Bureaucracy economy(Hezel, 2004).