Tuatapere Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Travel Report 2016-01-8-13 Tuatapere

8.1.2016 Tuatapere, Blue Cliffs Beach As we depart Lake Hauroko a big herd of sheep comes across our way. Due to our presence the sheep want to turn around immediately, but are forced to walk past us. The bravest sheep walks courageously in the front towards our car... Upon arriving in Tuatapere, the weather has changed completely. It is very windy and raining, so we decide to stop at the Cafe of the Last Light Lodge, which was very cozy and played funky music. Afterwards we head down to the rivermouth of the Waiau and despite the stormy weather Werner goes fishing. While we are parked there, three German tourists get stuck with their car next to us, the pebbles right next to the track are unexpectedly soft. Werner helps to push them out and we continue our way to the Blue Cliffs Beach – the sign has made us curious. We find a sheltered spot near the rivermouth so Werner can continue fishing. He comes back with an eel! Now we have to research eel recipes. 1 9.1.2016 Colac Bay, Riverton The very strong wind has blown away all the grey clouds and is pounding the waves against the beach. The rolling stones make such a noise, it’s hard to hear you own voice. Nature at work… Again we pass by the beautiful Red Hot Poker and finally have a chance to take a photo. We continue South on the 99, coming through Orepuki and Monkey Island. When the first settlers landed here a monkey supposedly helped to pull the boats ashore, hence the name Monkey Island. -

Whatever Happened to Tuatapere? a Study on a Small Rural Community Pam Smith

Whatever happened to Tuatapere? A study on a small rural community Pam Smith Pam Smith has worked in the social work field for the past 25 years. She has worked with children and families within the community both in statutory and non-government organisations. She has held social worker and supervisor roles and is currently a supervisory Team Leader at Family Works Southland. This article was based on Pam’s thesis for her Master of Philosophy in Social Work at Massey University. Abstract Social workers working in the rural community do so within a rural culture. This culture has developed from historical and cultural influences from the generations before, from the impact of social and familial changes over the years and from current internal and external influences. These changes and influences make the rural people who they are today. This study was carried out on a small rural community in Western Southland. The purpose was to examine the impact on the community of social changes over the past 50 years. Eight long-term residents were interviewed. The results will be discussed within this article. Introduction Government policies, changes in international trade and markets, environmental policies, globalisation, change in the structure of local and regional government and legislative changes, impacted on all New Zealanders during the past 50 years. The rural hinterland of New Zealand was affected in particular ways. The population in rural communities has been slowly decreasing over the years as ur- banisation has been a reality in New Zealand. Services within the area have diminished and younger families have moved away to seek employment elsewhere. -

Tuatapere Amenities Trust Fund Sponsored

Western Wanderer COLAC BAY OREPUKI TUATAPERE CLIFDEN ORAWIA BLACKMOUNT MONOWAI Tuatapere Amenities Trust Fund Sponsored Printed by Waiau Area School (03) 226-6285 ISSUE NUMBER: 178 Editor: Ph 027 462 9527 e-Mail: [email protected] APRIL2015 Closing Date for next copy: Friday, 8TH MAY2015 I hope everyone had a great Easter Inside this issue: and break away, just like to thank Councillor Community Board Notice everyone again for all their patience 2 and support while I get my head Community Notice Board 3/4 Midwife-Isobel / Comm Worker/ around the wanderer. wildthings/Toy Library sewing & mending/WD Joinery 5 Cheers. Loretta. Ross Burgess/Accounting/ Drake plumbling Waiau Town & Country Club Citizens Advice/Shirley Whyte 6 TJS tractor servicing/ 7 H&L Gill Fencing/Ann Sutherland / 25th April Anzac Day library Fowle/Tuatapere Handyman 8/9 Local Anzac Day services will be at Orawia at 7 00 Otautau Vets Ltd Electrician/Promotions/Forde 10/11 am followed by a cup of tea and a small bite to eat Shearing/Sutherland Contracting/ Waihape Photography/Tui Ameni- at the Orawia community hall which will then be ties Trust/ The Beauty Room followed by the Tuatapere service at 10 am which Crack 12 Dagwood Dagging/ Canterbury 13/14 will also be followed by a cup of tea and a bite to Cars/ Clifton Trading and Repairs Colac Bay Tavern eat at the RSA hall where we will have a guest Last light/ Target shooting/ 15/16 harvest festival/Playcentre/ 17/18 speaker present, please come along and pay your Highway 99/ growplan/D Unahi respects to our fallen soldiers and past and present Ryal Bush/ISBT Therapy/ 19/20 Budget Advice/ Waiau health 21/22 service members. -

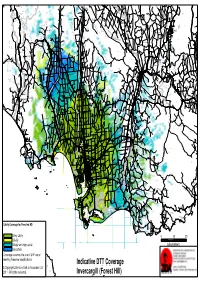

Indicative DTT Coverage Invercargill (Forest Hill)

Blackmount Caroline Balfour Waipounamu Kingston Crossing Greenvale Avondale Wendon Caroline Valley Glenure Kelso Riversdale Crossans Corner Dipton Waikaka Chatton North Beaumont Pyramid Tapanui Merino Downs Kaweku Koni Glenkenich Fleming Otama Mt Linton Rongahere Ohai Chatton East Birchwood Opio Chatton Maitland Waikoikoi Motumote Tua Mandeville Nightcaps Benmore Pomahaka Otahu Otamita Knapdale Rankleburn Eastern Bush Pukemutu Waikaka Valley Wharetoa Wairio Kauana Wreys Bush Dunearn Lill Burn Valley Feldwick Croydon Conical Hill Howe Benio Otapiri Gorge Woodlaw Centre Bush Otapiri Whiterigg South Hillend McNab Clifden Limehills Lora Gorge Croydon Bush Popotunoa Scotts Gap Gordon Otikerama Heenans Corner Pukerau Orawia Aparima Waipahi Upper Charlton Gore Merrivale Arthurton Heddon Bush South Gore Lady Barkly Alton Valley Pukemaori Bayswater Gore Saleyards Taumata Waikouro Waimumu Wairuna Raymonds Gap Hokonui Ashley Charlton Oreti Plains Kaiwera Gladfield Pikopiko Winton Browns Drummond Happy Valley Five Roads Otautau Ferndale Tuatapere Gap Road Waitane Clinton Te Tipua Otaraia Kuriwao Waiwera Papatotara Forest Hill Springhills Mataura Ringway Thomsons Crossing Glencoe Hedgehope Pebbly Hills Te Tua Lochiel Isla Bank Waikana Northope Forest Hill Te Waewae Fairfax Pourakino Valley Tuturau Otahuti Gropers Bush Tussock Creek Waiarikiki Wilsons Crossing Brydone Spar Bush Ermedale Ryal Bush Ota Creek Waihoaka Hazletts Taramoa Mabel Bush Flints Bush Grove Bush Mimihau Thornbury Oporo Branxholme Edendale Dacre Oware Orepuki Waimatuku Gummies Bush -

Clifden Suspension Bridge, Waiau River

th IPENZ Engineering Heritage Register Report Clifden Suspension Bridge, Waiau River Written by: Karen Astwood Date: 3 September 2012 Clifden Suspension Bridge, newly completed, circa February 1899. Collection of Southland Museum and Art Gallery 1 Contents A. General information ........................................................................................................... 3 B. Description ......................................................................................................................... 5 Summary ................................................................................................................................. 5 Historical narrative .................................................................................................................... 6 Social narrative ...................................................................................................................... 11 Physical narrative ................................................................................................................... 12 C. Assessment of significance ............................................................................................. 16 D. Supporting information ...................................................................................................... 17 List of supporting documents ................................................................................................... 17 Bibliography .......................................................................................................................... -

The New Zealand Gazette. 883

MAR. 25.] THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. 883 MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continued. MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continued. 533250 Daumann, Frederick Charles, farm labourer, care of post- 279563 Field, Sydney James, machinist, care of Post-office, Mac office, Lovells Flat. lennan, Catlins. 576554 Davis, Arthur Charles, farm labourer, Dipton. 495725 Field, William Henry, fitter and turner, 36 Princes St. 499495 Davis, Kenneth Henry, freezing worker, Dipton St. 551404 Findlay, Donald Malcolm, cheesemaker, care of Seaward 575914 Davis, Verdun John Lorraine, second-hand dealer, 32 Eye St. Downs Dairy Co., Seaward Downs, Southland. 578471 Dawson, Alan Henry, salesman, 83 Robertson St. 498399 Finn, Arthur Henry, farmer, Wallacetown. 590521 Dawson, John Alfred, rabbiter, care of Len Stewart, Esq., 498400 Finn, Henry George, mill worker, Stewart St., Balclutha. West Plains Rural Delivery. 622455 Fitzpatrick, Matthew Joseph, messenger, Merioneth St., 611279 Dawson, Lewis Alfred, oysterman, 199 Barrow St., Bluff. Arrowtown. 573736 Dawson, Morell Tasman, Jorry-driver, 12 Camden St. 553428 Flack, Charles Albert, labourer, Albion St., Mataura. 591145 Dawson, William Peters, carrier, Pa1merston St., Riverton. 562423 Fleet, Trevor, omnibus-driver, 305 Tweed St. 622362 De La Mare, William Lewis, factory worker, 106 Windsor St. 404475 Flowers, Gord<;m Sydney, labourer, 270 Tweed St. 623417 De Lautour, Peter Arnaud, bank officer, care of Bank of 536899 Forbes, William, farmer, Lochiel Rural Delivery. N.Z., Roxburgh. 492676 Ford, Leo Peter, fibrous-plasterer, 82 Islington St. 490649 Dempster, George Campbell, porter, 24 Oxford St., Gore. 492680 Forde, John Edmond, surfaceman, Maclennan, Catlins. 526266 Dempster, Victor Trumper, grocer, 20 Fulton St. 492681 Forde, John Francis, transport-driver, North Rd., Colling- 493201 Denham, Stuart Clarence, linesman, 81 Pomona St. -

Tuatapere-Community-Response-Plan

NTON Southland has NO Civil Defence sirens (fire brigade sirens are not used as warnings for a Civil Defence emergency) Tuatapere Community Response Plan 2018 If you’d like to become part of the Tuatapere Community Response Group Please email [email protected] Find more information on how you can be prepared for an emergency www.cdsouthland.nz Community Response Planning In the event of an emergency, communities may need to support themselves for up to 10 days before assistance arrives. The more prepared a community is, the more likely it is that the community will be able to look after themselves and others. This plan contains a short demographic description of Tuatapere, information about key hazards and risks, information about Community Emergency Hubs where the community can gather, and important contact information to help the community respond effectively. Members of the Tuatapere Community Response Group have developed the information contained in this plan and will be Emergency Management Southland’s first point of community contact in an emergency. Demographic details • Tuatapere is contained within the Southland District Council area; • The Tuatapere area has a population of approximately 1,940. Tuatapere has a population of about 558; • The main industries in the area include agriculture, forestry, sawmilling, fishing and transportation; • The town has a medical centre, ambulance, police and fire service. There are also fire stations at Orepuki and Blackmount; • There are two primary schools in the area. Waiau Area School and Hauroko Primary School, as well as various preschool options; • The broad geographic area for the Tuatapere Community Response Plan includes lower southwest Fiordland, Lake Hauroko, Lake Monowai, Blackmount, Cliften, Orepuki and Pahia, see the map below for a more detailed indication; • This is not to limit the area, but to give an indication of the extent of the geographic district. -

Consequences to Threatened Plants and Insects of Fragmentation of Southland Floodplain Forests

Consequences to threatened plants and insects of fragmentation of Southland floodplain forests S. Walker, G.M. Rogers, W.G. Lee, B. Rance, D. Ward, C. Rufaut, A. Conn, N. Simpson, G. Hall, and M-C. Larivière SCIENCE FOR CONSERVATION 265 Published by Science & Technical Publishing Department of Conservation PO Box 10–420 Wellington, New Zealand Cover: The Dean Burn: the largest tracts of floodplain forest ecosystem remaining on private land in Southland, New Zealand. (See Appendix 1 for more details.) Photo: Geoff Rogers, RD&I, DOC. Science for Conservation is a scientific monograph series presenting research funded by New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC). Manuscripts are internally and externally peer-reviewed; resulting publications are considered part of the formal international scientific literature. Individual copies are printed, and are also available from the departmental website in pdf form. Titles are listed in our catalogue on the website, refer www.doc.govt.nz under Publications, then Science and Research. © Copyright April 2006, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISSN 1173–2946 ISBN 0–478–14070–3 This report was prepared for publication by Science & Technical Publishing; editing by Geoff Gregory and layout by Ian Mackenzie. Publication was approved by the Chief Scientist (Research, Development & Improvement Division), Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. In the interest of forest conservation, we support paperless electronic publishing. When printing, recycled paper is used wherever possible. CONTENTS -

Southland Trail Notes Contents

22 October 2020 Southland trail notes Contents • Mararoa River Track • Tākitimu Track • Birchwood to Merrivale • Longwood Forest Track • Long Hilly Track • Tīhaka Beach Track • Oreti Beach Track • Invercargill to Bluff Mararoa River Track Route Trampers continuing on from the Mavora Walkway can walk south down and around the North Mavora Lake shore to the swingbridge across the Mararoa River at the lake’s outlet. From here the track is marked and sign-posted. It stays west of but proximate to the Mararoa River and then South Mavora Lake to this lake’s outlet where another swingbridge provides an alternative access point from Mavora Lakes Road. Beyond this swingbridge, the track continues down the true right side of the Mararoa River to a third and final swing bridge. Along the way a careful assessment is required: if the Mararoa River can be forded safely then Te Araroa Trampers can continue down the track on the true right side to the Kiwi Burn then either divert 1.5km to the Kiwi Burn Hut, or ford the Mararoa River and continue south on the true left bank. If the Mararoa is not fordable then Te Araroa trampers must cross the final swingbridge. Trampers can then continue down the true left bank on the riverside of the fence and, after 3km, rejoin the Te Araroa opposite the Kiwi Burn confluence. 1 Below the Kiwi Burn confluence, Te Araroa is marked with poles down the Mararoa’s true left bank. This is on the riverside of the fence all the way down to Wash Creek, some 16km distant. -

The Climate and Weather of Southland

THE CLIMATE AND WEATHER OF SOUTHLAND 2nd edition G.R. Macara © 2013. All rights reserved. The copyright for this report, and for the data, maps, figures and other information (hereafter collectively referred to as “data”) contained in it, is held by NIWA. This copyright extends to all forms of copying and any storage of material in any kind of information retrieval system. While NIWA uses all reasonable endeavours to ensure the accuracy of the data, NIWA does not guarantee or make any representation or warranty (express or implied) regarding the accuracy or completeness of the data, the use to which the data may be put or the results to be obtained from the use of the data. Accordingly, NIWA expressly disclaims all legal liability whatsoever arising from, or connected to, the use of, reference to, reliance on or possession of the data or the existence of errors therein. NIWA recommends that users exercise their own skill and care with respect to their use of the data and that they obtain independent professional advice relevant to their particular circumstances. NIWA SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY SERIES NUMBER 63 ISSN 1173-0382 Note to Second Edition This publication replaces the first edition of New Zealand Meteorological Service Miscellaneous Publication 115 (15), written in 1984 by J. Sansom. It was considered necessary to update the first edition, incorporating more recent data and updated methods of climatological variable calculation. THE CLIMATE AND WEATHER OF SOUTHLAND 2nd edition G. R. Macara CONTENTS SUMMARY 6 INTRODUCTION 7 TYPICAL -

Short Walks 2 up April 11

a selection of Southland s short walks contents pg For the location of each walk see the centre page map on page 17 and 18. Introduction 1 Information 2 Track Symbols 3 1 Mavora Lakes 5 2 Piano Flat 6 3 Glenure Allan Reserve 7 4 Waikaka Way Walkway 8 5 Croydon Bush, Dolamore Park Scenic Reserves 9,10 6 Dunsdale Reserve 11 7 Forest Hill Scenic Reserve 12 8 Kamahi/Edendale Scenic Reserve 13 9 Seaward Downs Scenic Reserve 13 10 Kingswood Bush Scenic Reserve 14 11 Borland Nature Walk 14 12 Tuatapere Scenic Reserve 15 13 Alex McKenzie Park and Arboretum 15 14 Roundhill 16 Location of walks map 17,18 15 Mores Scenic Reserve 19,20 16 Taramea Bay Walkway 20 17 Sandy Point Domain 21-23 18 Invercargill Estuary Walkway 24 19 Invercargill Parks & Gardens 25 20 Greenpoint Reserve 26 21 Bluff Hill/Motupohue 27,28 22 Waituna Viewing Shelter 29 23 Waipapa Point 30 24 Waipohatu Recreation Area 31 25 Slope Point 32 26 Waikawa 32 27 Curio Bay 33 Wildlife viewing 34 Walks further afield 35 For more information 36 introduction to short Southland s walking tracks short walks Short walking tracks combine healthy exercise with the enjoyment of beautiful places. They take between 15 minutes and 4 hours to complete Southland is renowned for challenging tracks that are generally well formed and maintained venture into wild and rugged landscapes. Yet many of can be walked in sensible leisure footwear the region's most attractive places can be enjoyed in a are usually accessible throughout the year more leisurely way – without the need for tramping boots are suitable for most ages and fitness levels or heavy packs. -

CSC-News-2015-04.Pdf

Central Southland College To all new prospecve students and families you are invited to our Open Night Thursday July 23rd (7-9 pm) Newsletter Principal: Grant Dick 26th June 2015 [email protected] or www.csc.school.nz Grange Street, PO Box 94 Winton Phone 03 236 7646 CSC SPORTEditorial REPORT During week one of this term the Education Review office visited our school and completed an in- depth review of our schools performance. The confirmed report of ERO’s findings has now been released and this is available on our website. Below is an example of the many positive comments that were made in the report: “Students learn in a positive environment. There are effective systems for promoting student wellbeing and achievement. Deans know their students well as learners and individuals. The extent of students’ involvement in school activities is considerable. ERO noted students were very busy participating in a wide range of events/activities.” ERO 2015 “Students benefit from a broad and rich curriculum. They appreciate the many sports, cultural and beyond the classroom learning experiences. There is a focus on ensuring that students grow to be well-rounded adults. This aligns with parents’ aspirations.” ERO 2015 Dunstan High School Annual exchange was held last week and congratulations go to Dunstan who took out the overall competition. Many of our teams had some great results and all our students competed with passion and pride. Well done to all those involved and a special thanks to the families that hosted Billets. ‘Back to the Eighties’, our 2015 school production, is on stage next week.