Whatever Happened to Tuatapere? a Study on a Small Rural Community Pam Smith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Travel Report 2016-01-8-13 Tuatapere

8.1.2016 Tuatapere, Blue Cliffs Beach As we depart Lake Hauroko a big herd of sheep comes across our way. Due to our presence the sheep want to turn around immediately, but are forced to walk past us. The bravest sheep walks courageously in the front towards our car... Upon arriving in Tuatapere, the weather has changed completely. It is very windy and raining, so we decide to stop at the Cafe of the Last Light Lodge, which was very cozy and played funky music. Afterwards we head down to the rivermouth of the Waiau and despite the stormy weather Werner goes fishing. While we are parked there, three German tourists get stuck with their car next to us, the pebbles right next to the track are unexpectedly soft. Werner helps to push them out and we continue our way to the Blue Cliffs Beach – the sign has made us curious. We find a sheltered spot near the rivermouth so Werner can continue fishing. He comes back with an eel! Now we have to research eel recipes. 1 9.1.2016 Colac Bay, Riverton The very strong wind has blown away all the grey clouds and is pounding the waves against the beach. The rolling stones make such a noise, it’s hard to hear you own voice. Nature at work… Again we pass by the beautiful Red Hot Poker and finally have a chance to take a photo. We continue South on the 99, coming through Orepuki and Monkey Island. When the first settlers landed here a monkey supposedly helped to pull the boats ashore, hence the name Monkey Island. -

Tuatapere Amenities Trust Fund Sponsored

Western Wanderer COLAC BAY OREPUKI TUATAPERE CLIFDEN ORAWIA BLACKMOUNT MONOWAI Tuatapere Amenities Trust Fund Sponsored Printed by Waiau Area School (03) 226-6285 ISSUE NUMBER: 178 Editor: Ph 027 462 9527 e-Mail: [email protected] APRIL2015 Closing Date for next copy: Friday, 8TH MAY2015 I hope everyone had a great Easter Inside this issue: and break away, just like to thank Councillor Community Board Notice everyone again for all their patience 2 and support while I get my head Community Notice Board 3/4 Midwife-Isobel / Comm Worker/ around the wanderer. wildthings/Toy Library sewing & mending/WD Joinery 5 Cheers. Loretta. Ross Burgess/Accounting/ Drake plumbling Waiau Town & Country Club Citizens Advice/Shirley Whyte 6 TJS tractor servicing/ 7 H&L Gill Fencing/Ann Sutherland / 25th April Anzac Day library Fowle/Tuatapere Handyman 8/9 Local Anzac Day services will be at Orawia at 7 00 Otautau Vets Ltd Electrician/Promotions/Forde 10/11 am followed by a cup of tea and a small bite to eat Shearing/Sutherland Contracting/ Waihape Photography/Tui Ameni- at the Orawia community hall which will then be ties Trust/ The Beauty Room followed by the Tuatapere service at 10 am which Crack 12 Dagwood Dagging/ Canterbury 13/14 will also be followed by a cup of tea and a bite to Cars/ Clifton Trading and Repairs Colac Bay Tavern eat at the RSA hall where we will have a guest Last light/ Target shooting/ 15/16 harvest festival/Playcentre/ 17/18 speaker present, please come along and pay your Highway 99/ growplan/D Unahi respects to our fallen soldiers and past and present Ryal Bush/ISBT Therapy/ 19/20 Budget Advice/ Waiau health 21/22 service members. -

Welcoming Plan — Southland

Southland Murihiku Welcoming Plan 2019 2 Nau mai haere mai ki Murihiku, Welcome to Southland Foreword From Our Regional Leaders As leaders of this thriving and expansive region, To guide the implementation of this approach in we recognise that a regional approach to fostering Southland, and to encourage greater interaction diversity and inclusion will underpin the success of between people, a Welcoming Plan has been our future communities. developed for Southland/Murihiku. Southland has been selected as one of five pilot We are proud to endorse this Welcoming Plan and areas for the Immigration New Zealand Welcoming know that Southland will rise to the occasion to Communities programme, and as such becomes a build on the inclusive foundations already set in forerunner of the Welcoming Movement operating the region. across the world. The challenge is now over to you to join us in This movement encourages the development of embracing this welcoming approach, to get involved, a worldwide network where an inclusive approach and help make Southland the most welcoming is adopted to welcome new people to our place possible! communities. Sir Tim Shadbolt, KNZM Gary Tong Tracy Hicks Nicol Horrell Invercargill City Council Mayor Southland District Council Mayor Gore District Council Mayor Environment Southland Chairman 3 4 Contents 6 Executive Summary 9 Welcoming Communities Context 10 Why Southland 12 Welcoming Plan Development 14 Southland/Murihiku Welcoming Plan Outcomes and Actions 16 Inclusive Leadership 18 Welcoming Communications 20 Equitable Access 21 Connected and Inclusive Communities 22 Economic Development, Business and Employment 25 Civic Engagement and Participation 26 Welcoming Public Spaces 27 Culture and Identity 28 Implementation 29 Developing Regional Projects 30 Encouraging Council Planning 30 Partnering With Tangata Whenua 31 Fostering Community Partnership and Support 33 Conclusion 5 Executive Summary Ten councils across five regions, including social, cultural and economic participation. -

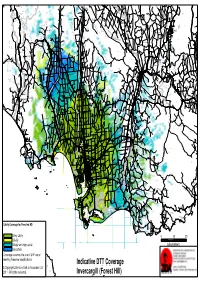

Indicative DTT Coverage Invercargill (Forest Hill)

Blackmount Caroline Balfour Waipounamu Kingston Crossing Greenvale Avondale Wendon Caroline Valley Glenure Kelso Riversdale Crossans Corner Dipton Waikaka Chatton North Beaumont Pyramid Tapanui Merino Downs Kaweku Koni Glenkenich Fleming Otama Mt Linton Rongahere Ohai Chatton East Birchwood Opio Chatton Maitland Waikoikoi Motumote Tua Mandeville Nightcaps Benmore Pomahaka Otahu Otamita Knapdale Rankleburn Eastern Bush Pukemutu Waikaka Valley Wharetoa Wairio Kauana Wreys Bush Dunearn Lill Burn Valley Feldwick Croydon Conical Hill Howe Benio Otapiri Gorge Woodlaw Centre Bush Otapiri Whiterigg South Hillend McNab Clifden Limehills Lora Gorge Croydon Bush Popotunoa Scotts Gap Gordon Otikerama Heenans Corner Pukerau Orawia Aparima Waipahi Upper Charlton Gore Merrivale Arthurton Heddon Bush South Gore Lady Barkly Alton Valley Pukemaori Bayswater Gore Saleyards Taumata Waikouro Waimumu Wairuna Raymonds Gap Hokonui Ashley Charlton Oreti Plains Kaiwera Gladfield Pikopiko Winton Browns Drummond Happy Valley Five Roads Otautau Ferndale Tuatapere Gap Road Waitane Clinton Te Tipua Otaraia Kuriwao Waiwera Papatotara Forest Hill Springhills Mataura Ringway Thomsons Crossing Glencoe Hedgehope Pebbly Hills Te Tua Lochiel Isla Bank Waikana Northope Forest Hill Te Waewae Fairfax Pourakino Valley Tuturau Otahuti Gropers Bush Tussock Creek Waiarikiki Wilsons Crossing Brydone Spar Bush Ermedale Ryal Bush Ota Creek Waihoaka Hazletts Taramoa Mabel Bush Flints Bush Grove Bush Mimihau Thornbury Oporo Branxholme Edendale Dacre Oware Orepuki Waimatuku Gummies Bush -

Clifden Suspension Bridge, Waiau River

th IPENZ Engineering Heritage Register Report Clifden Suspension Bridge, Waiau River Written by: Karen Astwood Date: 3 September 2012 Clifden Suspension Bridge, newly completed, circa February 1899. Collection of Southland Museum and Art Gallery 1 Contents A. General information ........................................................................................................... 3 B. Description ......................................................................................................................... 5 Summary ................................................................................................................................. 5 Historical narrative .................................................................................................................... 6 Social narrative ...................................................................................................................... 11 Physical narrative ................................................................................................................... 12 C. Assessment of significance ............................................................................................. 16 D. Supporting information ...................................................................................................... 17 List of supporting documents ................................................................................................... 17 Bibliography .......................................................................................................................... -

NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 1237 Measured South-Easterly, Generally, Along the Said State 2

30 APRIL NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE 1237 measured south-easterly, generally, along the said State 2. New Zealand Gazette, No. 35, dated 1 June 1967, page highway from Maria Street. 968. Situated within Southland District at Manapouri: 3. New Zealand Gazette, No. 26, dated 3 March 1983, page Manapouri-Hillside Road: from Waiau Street to a point 571. 500 metres measured easterly, generally, along the said road 4. New Zealand Gazette, No. 22, dated 25 February 1982, from Waiau Street. page 599. Manapouri-Te Anau Road: from Manapouri-Hillside Road to a 5. New Zealand Gazette, No. 94, dated 7 June 1984, page point 900 metres measured north-easterly, generally, along 1871. Manapouri-Te Anau Road from Manapouri-Hillside Road. 6. New Zealand Gazette, No. 20, dated 29 March 1962, page Situated within Southland District at Ohai: 519. No. 96 State Highway (Mataura-Tuatapere): from a point 7. New Zealand Gazette, No. 8, dated 19 February 1959, 250 metres measured south-westerly, generally, along the said page 174. State highway from Cottage Road to Duchess Street. 8. New Zealand Gazette, No. 40, dated 22 June 1961, page Situated within Southland District at Orawia: 887. No. 96 State Highway (Mataura-Tuatapere): from the south 9. New Zealand Gazette, No. 83, dated 23 October 1941, western end of the bridge over the Orauea River to a point 550 page 3288. metres measured south-westerly, generally, along the said 10. New Zealand Gazette, No.107, dated 21 June 1984, page State highway from the said end of the bridge over the Orauea 2277. River. -

Kids Voting Registered Schools

Name of School Address City or district General council area Electorate Cromwell College Barry Ave, Cromwell Central Otago Waitaki 9310 District Council Aidanfield Christian Nash Road, Oaklands, Christchurch City Wigram School 8025 Council Heaton Normal Heaton Street, Merivale, Christchurch City Ilam Intermediate Christchurch 8052 Council Queen's High School Surrey Street, St Clair, Dunedin City Dunedin South Dunedin 9012 Council Columba College Highgate, Kaikorai, Dunedin City Dunedin North Dunedin 9010 Council Longford Intermediate Wayland Street, Gore Gore District Clutha-Southland 9710 Council Sacred Heart Girls' Clyde Street, Hamilton Hamilton City Hamilton East College East, Hamilton 3216 Council Hamilton Girls' High Ward Street, Hamilton Hamilton City Hamilton West School 3204 Council Peachgrove Peachgrove Road, Hamilton City Hamilton East Intermediate Hamilton 3216 Council Karamu High School Windsor Ave, Hastings, Hastings District Tukituki 4122 Council Hastings Christian Copeland Road, Hawkes Hastings District Tukituki School Bay 4122 Council Taita College Eastern Hutt Road, Hutt City Council Rimutaka Holborn 5019 Avalon Intermediate High Street, Avalon, Hutt City Council Rimutaka School Lower Hutt 5011 St Oran's College High Street, Boulcott, Hutt City Council Hutt South Lower Hutt 5010 Naenae Intermediate Walters Street, Avalon, Hutt City Council Rimutaka Lower Hutt 5011 Sacred Heart College Laings Road, Lower hutt Hutt City Council Rimutaka 5010 Southland Boys' High Herbert Street, Invercargiill City Invercargill School Invercargill -

The New Zealand Gazette. 883

MAR. 25.] THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE. 883 MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continued. MILITARY AREA No. 12 (INVERCARGILL)-continued. 533250 Daumann, Frederick Charles, farm labourer, care of post- 279563 Field, Sydney James, machinist, care of Post-office, Mac office, Lovells Flat. lennan, Catlins. 576554 Davis, Arthur Charles, farm labourer, Dipton. 495725 Field, William Henry, fitter and turner, 36 Princes St. 499495 Davis, Kenneth Henry, freezing worker, Dipton St. 551404 Findlay, Donald Malcolm, cheesemaker, care of Seaward 575914 Davis, Verdun John Lorraine, second-hand dealer, 32 Eye St. Downs Dairy Co., Seaward Downs, Southland. 578471 Dawson, Alan Henry, salesman, 83 Robertson St. 498399 Finn, Arthur Henry, farmer, Wallacetown. 590521 Dawson, John Alfred, rabbiter, care of Len Stewart, Esq., 498400 Finn, Henry George, mill worker, Stewart St., Balclutha. West Plains Rural Delivery. 622455 Fitzpatrick, Matthew Joseph, messenger, Merioneth St., 611279 Dawson, Lewis Alfred, oysterman, 199 Barrow St., Bluff. Arrowtown. 573736 Dawson, Morell Tasman, Jorry-driver, 12 Camden St. 553428 Flack, Charles Albert, labourer, Albion St., Mataura. 591145 Dawson, William Peters, carrier, Pa1merston St., Riverton. 562423 Fleet, Trevor, omnibus-driver, 305 Tweed St. 622362 De La Mare, William Lewis, factory worker, 106 Windsor St. 404475 Flowers, Gord<;m Sydney, labourer, 270 Tweed St. 623417 De Lautour, Peter Arnaud, bank officer, care of Bank of 536899 Forbes, William, farmer, Lochiel Rural Delivery. N.Z., Roxburgh. 492676 Ford, Leo Peter, fibrous-plasterer, 82 Islington St. 490649 Dempster, George Campbell, porter, 24 Oxford St., Gore. 492680 Forde, John Edmond, surfaceman, Maclennan, Catlins. 526266 Dempster, Victor Trumper, grocer, 20 Fulton St. 492681 Forde, John Francis, transport-driver, North Rd., Colling- 493201 Denham, Stuart Clarence, linesman, 81 Pomona St. -

Tuatapere-Community-Response-Plan

NTON Southland has NO Civil Defence sirens (fire brigade sirens are not used as warnings for a Civil Defence emergency) Tuatapere Community Response Plan 2018 If you’d like to become part of the Tuatapere Community Response Group Please email [email protected] Find more information on how you can be prepared for an emergency www.cdsouthland.nz Community Response Planning In the event of an emergency, communities may need to support themselves for up to 10 days before assistance arrives. The more prepared a community is, the more likely it is that the community will be able to look after themselves and others. This plan contains a short demographic description of Tuatapere, information about key hazards and risks, information about Community Emergency Hubs where the community can gather, and important contact information to help the community respond effectively. Members of the Tuatapere Community Response Group have developed the information contained in this plan and will be Emergency Management Southland’s first point of community contact in an emergency. Demographic details • Tuatapere is contained within the Southland District Council area; • The Tuatapere area has a population of approximately 1,940. Tuatapere has a population of about 558; • The main industries in the area include agriculture, forestry, sawmilling, fishing and transportation; • The town has a medical centre, ambulance, police and fire service. There are also fire stations at Orepuki and Blackmount; • There are two primary schools in the area. Waiau Area School and Hauroko Primary School, as well as various preschool options; • The broad geographic area for the Tuatapere Community Response Plan includes lower southwest Fiordland, Lake Hauroko, Lake Monowai, Blackmount, Cliften, Orepuki and Pahia, see the map below for a more detailed indication; • This is not to limit the area, but to give an indication of the extent of the geographic district. -

Southland Civil Defence Emergency Management Group Agenda.Docx

Committee Members Mayor Tim Shadbolt, Invercargill City Council Cr Neville Cook, Environment Southland (Chair) Mayor Gary Tong, Southland District Council Mayor Tracy Hicks, Gore District Council or their alternates Southland Civil Defence Emergency Management Group (Te Manatu Arai Mate Ohorere o te Tonga) Council Chambers 10.00 am Environment Southland 8 November 2019 Cnr Price Street and North Road Invercargill A G E N D A (Rarangi Take) 1. Welcome (Haere mai) 2. Apologies (Nga Pa Pouri) 3. Declarations of Interest 4. Public Forum, Petitions and Deputations (He Huinga tuku korero) 5. Confirmation of Minutes (Whakau korero) – 15 March 2019 6. Notification of Extraordinary and Urgent Business (He Panui Autaia hei Totoia Pakihi) 6.1 Supplementary Reports 6.2 Other 7. Questions (Patai) 8. Chairman’s Report (Te Purongo a Tumuaki) 9. Report – 19/SCDEMG/93 Item 1 - Election of Chairperson and Deputy Chairperson .............................................11 Item 2 - Co-ordinating Executive Group (CEG) Chair Report ..........................................12 Item 3 - Health & Safety ..................................................................................................13 Item 4 – EMS Annual Report ...........................................................................................14 Item 5 – AF8 [Alpine Fault magnitude 8] ........................................................................27 Item 6 – EMS Update and Work Programme ..................................................................41 Item 7 – Transition -

New Accessibility Map for Southland District Council Area

SOUTHERN REGION JULY 2016 New Accessibility Map for Southland District Council Area Travelling around Southland will now be easier Council Offices and community organisations for disabled people; this is because the including CCS Disability Action branch offices Southland District Council has just published in Invercargill and Dunedin. People who want an accessibility map of Southland. As well as a copy can e-mail Janet Thomas for a copy showing accessible restaurants, toilets etc. the ([email protected]) or find the map shows accessible museums, libraries and map on the Southland District Council website walking tracks. The map also shows contact http://www.southlanddc.govt.nz/home/ details of restaurants etc. so that people can accessibility-map/ contact them for further information. The council has worked closely with disabled people to find out what they wanted in the map. As well as this Janet Thomas from the council visited fifty toilets in the area to make sure that they were accessible. Janet also advised people responsible for the toilets if repairs were necessary. Mel Smith, the Acting CCS Disability Action Southern Regional Manager said that the development of the map was a wonderful example of a council working with the disabled community to develop the map which will be of use to all. The map was developed as part of the Council’s inclusive communities strategy with funding from Think Differently. Copies of the map are available from Southland District In this Issue: Swipe Cards for Total Mobility Taxi Users in Otago ... 7 New Accessibility Map for Southland DC ................. -

Consequences to Threatened Plants and Insects of Fragmentation of Southland Floodplain Forests

Consequences to threatened plants and insects of fragmentation of Southland floodplain forests S. Walker, G.M. Rogers, W.G. Lee, B. Rance, D. Ward, C. Rufaut, A. Conn, N. Simpson, G. Hall, and M-C. Larivière SCIENCE FOR CONSERVATION 265 Published by Science & Technical Publishing Department of Conservation PO Box 10–420 Wellington, New Zealand Cover: The Dean Burn: the largest tracts of floodplain forest ecosystem remaining on private land in Southland, New Zealand. (See Appendix 1 for more details.) Photo: Geoff Rogers, RD&I, DOC. Science for Conservation is a scientific monograph series presenting research funded by New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC). Manuscripts are internally and externally peer-reviewed; resulting publications are considered part of the formal international scientific literature. Individual copies are printed, and are also available from the departmental website in pdf form. Titles are listed in our catalogue on the website, refer www.doc.govt.nz under Publications, then Science and Research. © Copyright April 2006, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISSN 1173–2946 ISBN 0–478–14070–3 This report was prepared for publication by Science & Technical Publishing; editing by Geoff Gregory and layout by Ian Mackenzie. Publication was approved by the Chief Scientist (Research, Development & Improvement Division), Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. In the interest of forest conservation, we support paperless electronic publishing. When printing, recycled paper is used wherever possible. CONTENTS