Lessons from the Bicol River Basin Development Program (BRBDP) and Other Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Small-Scale Fisheries of San Miguel Bay, Philippines: Occupational and Geographic Mobility

Small-scale fisheries of San Miguel Bay, Philippines: occupational and geographic mobility Conner Bailey 1982 INSTITUTE OF FISHERIES DEVELOPMENT AND RESEARCH COLLEGE OF FISHERIES, UNIVERSITY OF THE PHILIPPINES IN THE VISAYAS QUEZON CITY, PHILIPPINES INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR LIVING AQUATIC RESOURCES MANAGEMENT MANILA, PHILIPPINES THE UNITED NATIONS UNIVERSITY TOKYO, JAPAN Small-scale fisheries of San Miguel Bay, Philippines: occupational and geographic mobility CONNER BAILEY 1982 Published jointly by the Institute of Fisheries Development and Research, College of Fisheries, University of the Philippines in the Visayas, Quezon City, Philippines; the International Center for Living Aquatic Resources Management, Manila, Philippines; and the United Nations University,Tokyo, Japan. Printed in Manila, Philippines Bailey, C. 1982. Small-scale fisheries of San Miguel Bay, Philippines: occupational and geographic mobility. ICLARM Technical Reports 10, 57 p. Institute of Fisheries Development and Research, College of Fisheries, University of the Philippines in the Visayas, Quezon City, Philippines; International Center for Living Aquatic Resources Management, Manila, Philippines; and the United Nations University, Tokyo, Japan. Cover: Upper: Fishermen and buyers on the beach, San Miguel Bay. Lower: Satellite view of the Bay, to the right of center. [Photo, NASA, U.S.A.]. ISSN 0115-5547 ICLARM Contribution No. 137 Table of Contents List of Tables......................................................................... ................... ..................................... -

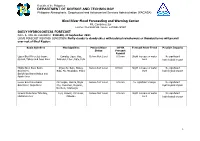

(PAGASA) Bicol River Flood Forecasting and Warning Center

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) BicolB Rivericol Ri verFlood Flood Forecasting Forecasting and and Warning Warning CenterCenter Pili, Camarines Sur Telefax: (054)88Pili,42049, Camarines Mobile: + Sur6399 96793903 DAILY HYDROLOGICAL FORECAST Telefax: (054)8842049, Mobile: +639996793903 DATE & TIME OF ISSUANCE: 9:00 AM, 23 September 2021 LOCAL FORECAST WEATHER CONDITION: Partly cloudy to cloudy skies with isolated rainshowers or thunderstorms will prevail over rest of Bicol Region. Basin Sub-Area Municipalities Present River 24-HR Forecast River Trend Possible Impacts Status Forecast Rainfall Upper Bicol River Sub-basin: Camalig, Ligao, Oas, Below Alert Level 0-5 mm Slight increase of water No significant Quinali, Talisay and Agos River Polangui, Libon, Bato, Buhi level hydrological impact Middle Bicol River Basin: Iriga City, Buhi, Nabua, Below Alert Level 0-5mm Slight increase of water No significant Bicol River, Bula, Pili, Minalabac, Milaor level hydrological impact Barit/Iriga/Waras,Nabua and Pawili River Lower Bicol River Basin Camaligan, Gainza, Naga Below Alert Level 0-5 mm No significant change No significant Bicol River, Naga River City, Canaman, Magarao, hydrological impact Bombon, Calabanga Sipocot-Pulantuna Tributary, Lupi, Sipocot, Libmanan, Below Alert Level 0-5 mm Slight increase of water No significant Libmanan river Cabusao level hydrological impact 1 Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF SCIENCE AND -

Integrated Bicol River Basin Management and Development Master Plan

Volume 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Integrated Bicol River Basin Management and Development Master Plan July 2015 With Technical Assistance from: Orient Integrated Development Consultants, Inc. Formulation of an Integrated Bicol River Basin Management and Development Master plan Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 2.0 KEY FEATURES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF THE BICOL RIVER BASIN ........................... 1 3.0 ASSESSMENT OF EXISTING SITUATION ........................................................................ 3 4.0 DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES ................................................... 9 5.0 VISION, GOAL, OBJECTIVES AND STRATEGIES ........................................................... 10 6.0 INVESTMENT REQUIREMENTS ................................................................................... 17 7.0 ECONOMIC ANALYSIS ................................................................................................. 20 8.0 ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF PROPOSED PROJECTS ....................................... 20 Vol 1: Executive Summary i | Page Formulation of an Integrated Bicol River Basin Management and Development Master plan 1.0 INTRODUCTION The Bicol River Basin (BRB) has a total land area of 317,103 hectares and covers the provinces of Albay, Camarines Sur and Camarines Norte. The basin plays a significant role in the development of the region because of the abundant resources within it and the ecological -

DENR-BMB Atlas of Luzon Wetlands 17Sept14.Indd

Philippine Copyright © 2014 Biodiversity Management Bureau Department of Environment and Natural Resources This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the Copyright holder provided acknowledgement of the source is made. BMB - DENR Ninoy Aquino Parks and Wildlife Center Compound Quezon Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City Philippines 1101 Telefax (+632) 925-8950 [email protected] http://www.bmb.gov.ph ISBN 978-621-95016-2-0 Printed and bound in the Philippines First Printing: September 2014 Project Heads : Marlynn M. Mendoza and Joy M. Navarro GIS Mapping : Rej Winlove M. Bungabong Project Assistant : Patricia May Labitoria Design and Layout : Jerome Bonto Project Support : Ramsar Regional Center-East Asia Inland wetlands boundaries and their geographic locations are subject to actual ground verification and survey/ delineation. Administrative/political boundaries are approximate. If there are other wetland areas you know and are not reflected in this Atlas, please feel free to contact us. Recommended citation: Biodiversity Management Bureau-Department of Environment and Natural Resources. 2014. Atlas of Inland Wetlands in Mainland Luzon, Philippines. Quezon City. Published by: Biodiversity Management Bureau - Department of Environment and Natural Resources Candaba Swamp, Candaba, Pampanga Guiaya Argean Rej Winlove M. Bungabong M. Winlove Rej Dumacaa River, Tayabas, Quezon Jerome P. Bonto P. Jerome Laguna Lake, Laguna Zoisane Geam G. Lumbres G. Geam Zoisane -

Bicol River Basin Pilot Project: the Philippines

URBAN FUNCTIONS IN RURAL DEVELOPMENT-- BICOL RIVER BASIN PILOT PROJECT: THE PHILIPPINES FIRST QUARTERLY REPORT: PROJECT DESIGN Dennis A. Rondinelli Consultant Contract No. AID/ta-C-1356 Office of Urban Development Technical Assistance Bureau Agency for International Development U.S. Department of State Washington, D. C. November 1976 CONTENTS TRIP REPORT--SUM4ARY OF ACTIVITIES ............................... 1 MAJOR ACTIVITIES, ISSUES AND PROBLEM AREAS ......................................................... 5 Clarification of Project Activities and Results ................. 5 Project Initiation .............................................. 8 Staff Organization .............................................. 8 Organization and Duties of GOP Senior Consultants ............... 9 Geographical Area of Project Coverage ............................. 10 Data Availability ............................................... 10 Coordination, Participation and Training ........................ 13 Directly Related Activities ..................................... 18 PLAN OF IHPLEIENTATION AND CONTRACTOR WORK PLAN .................. 22 GOP Plan of Implementation ...................................... 22 U.S. Consultant Activities and Work Plan ........................ 24 URBAN FUNCTIONS IN RURAL DEVELOPMENT--BICOL RIVER BASIN PROJECT FIRST QUARTERLY REPORT: PROJECT DESIGN ---------------------------------------------------------------------- Purpose of Visit: The visit was scheduled to discuss preliminary organization and design of the project with the -

PNAAK573.Pdf

BIB LIOGRAPHIC DATA SHEET IIa" NUMBER [ICONTROL2. S JECT CLASSIFICATION(695) 3.TITLE A N D SUBT ITLE (240) c . , - , , K ;, _ - 0 0-- (A LLA \ A. V - 4. ?ERSONAL AUTHOR (100) - 5. CORPORATE AUTHORS (101) 6. DOCUMENT DATE (110) _. 1 NUMBER OF PAGES (120) • 1 8.ARCNUMBER(1) 18 9. REFERENCE ORGANIZATION (130) 10. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES (500) CV V._- k2G- 11. ABSTRACT (950) .Cl 0 12. DESCRIPTORS (92 " 13. PROJECT NUMBER (150) " ' ' ' -." .\,,co____' _ -"c:C l ,M (2 - s14. CONTRACT NO.(14t1o.,,_,_,,,dI 5 CONTRACT_____'_,,'.. 16. TYPE OF DOCUMENT (16C) ;I 590-7 (10-79) BICOL RIVER BASIN. COMPREHENSIVE WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT STUDY 77 LUZON PHILI INES I 84YMANILA " "LOCATION N% MAP :i: i: " ':/:'""" 'oNAGA CIT2 LEGENDI RIVER BASIN BOUNDARY ... AREA SUBjECT TO FLOODING l> ' > S-FOOTHILLS ~ar VOLUME ill REPORT August 1976 TIPPETTS- ABBETT-McCARTHY -STRATTON BICOL RIVER BASIN DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM TRANS-A3IA ENGINEERING ASSOCIATES IINC. Joint Venlture Boras , Canaman Camrnl Svr' Now York Honululu PHILIPPINES COMPREHENSIVE WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT STUDY VOLUME NO. 3 APPENDIX TABLE OF CONTENTS A CLIMATE AND HYDROLOGY B MATHEMATICAL MODEL OF THE BICOL SYSTEM C WEATHER MODIFICATIONS D SALINITY STUDIES E SEDIMENTATION STUDIES Appendix A Climate and Hydrology August 1976 COMPREHENSIVE WATER RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT STUDY BICOL RIVER BASIN LUZON ISLAND, PHILIPPINES APPENDIX A CLIMATE AND HYDROLOGY AUGUST 1976 TAiS-TAE JOINT VENTURE BICOL RIVER BASIN DEVELOPMENT Now York Manila PROGRAM Baras, Canaman Camarines Sur APPENDIX A TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION -

List of Figures Figure 1 Overlay of Wqmas, 19 Priority River Basins

List of Figures Figure 1 Overlay of WQMAs, 19 priority river basins, and KBAs Figure 2 Ambient water quality management program sites of DENR–EMB Region 5 Figure 3 Location of existing mining tenements, with reference to protected areas and key biodiversity areas Figure 4 Location of illegal logging hotspots and their overlap with protected areas and Key Biodiversity Areas Figure 5 Wildlife crime hotspots in the Philippines Figure 6 Hotspot areas of illegal fishing in 2016 List of Tables Table 1 Number of invasive species documented in six protected areas that were pilot sites for the prevention, control, and management of IAS Table 2 Classification and usage of freshwater water bodies Table 3 Classification and usage of marine water bodies Table 4 Results of the water quality monitoring of the 19 priority rivers as of 2016.* * Values in bold mean that the river complies with DAO No. 34 Table 5 18 priority river basins, their rivers, and classifications Table 6 Number of illegal logging hotspots List of Footnotes 1 DENR-Biodiversity Management Bureau. 2016. The National Invasive Species Management Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2026 (Philippines. Quezon City: Department of Environment and Natural Resources- Biodiversity Management Bureau, pp. i-xix, 1-95. 2 DENR-Biodiversity Management Bureau. Protected Area Management Master Plan (draft). 3 FORIS Project (UNEP/GEF Project on Removing Barriers to Invasive Species Management in Production and Protection Forests in Southeast Asia). Powerpoint. 4 DENR-Biodiversity Management Bureau. 2016. The National Invasive Species Management Strategy and Action Plan 2016-2026 (Philippines. Quezon City: Department of Environment and Natural Resources- Biodiversity Management Bureau, pp. -

Naga City Tjrban Dettelopme\It and Iiousing Board (Nci,'Dbei

ヽ REPulLIC OF THE PHiLIPHNES OFFICE OF THE CI]nr MAYOR CIfyびNFy EXECIrrm oRDER NO.2013‐ 。印 RECONSTITUTING TEE NAGA CITY TJRBAN DETTELOPME\IT AND IIOUSING BOARD (NCI,'DBEI WEEREAS, Section E, Aftide 6 of Ordinanc€ no. 9t-033 mardates for the Geation of Naga Ciry Urban Developmert and Housing Board (NCUDHB) which acts as the city's arm in the implementation ard monitoring ofpertinent provision of Republic Act No. 7279 and ordinance no 98403; Whereas, the same section spea.ts of appointnent by the Ciry Mayor for members of the Board ftom the private ;ector; .WEEREAS, received by the office of the City Mayor on 30 July 2013 is a leflgr datrd 22 luly 201 3 ftom the NaSa City Urban poor Fed€ration, Inc. eudorsing the individuals &om uf,ban poor organization as members ofthe Board; WIIEREAS, there,is a need to reorganize the composition of the Naga City Urban Developmert and Housing Board due to the changi in the leaderhip-and in order to d€liver ib seryices and to carry out all is prograrls and proJects foithe good and welfare ofthe constituenB ofthe City ofNaga; a powers vested in m€ by law, do hereby order for the reconstitution ofttre liaga'City ' Urban Development and Housing Board (NCLJDHB) to be composed by thJ following: _ - !:q[-m LCompocition. The Naga City Urban Development arrd Housing- Board (NCUDHB) is hereby reorganized o te-composca ofthe foUowinl; Hon. D-avrd Casper Nathan Sergio, Chairman, Committee on Lan dUse- 1y'. Hon. Mila S.D. Raquid Arroyo, Chairman, Committee on Urban pooi a-daus Hon. -

Naga City Comprehensive Land Use Plan 2000 I

NAGA CITY COMPREHENSIVE LAND USE PLAN 2000 Naga City Comprehensive Land Use Plan 2000 i. Foreword ii. Acknowledgment The Comprehensive Land Use Plan (CLUP) is a vital The framers of the Naga City Comprehensive Land Use instrument in achieving an equitable and balanced development in Plan (CLUP) 2000 wish to extend their sincerest gratitude to the any given locality. It brings forth the judicious and sustainable use of following persons and agencies for their valuable contribution the city’s physical and socio-economic resources --- its proper in completing this document: allocation and regulation. For completing the Demography Sector: the National Census The CLUP guides leaders in demarcating areas which will and Statistics Office (NSO), the City Population and Nutrition Office strategically yield optimum production and increased efficiency of (CPNO), Mrs. Teresita A. Del Castillo, Engr. Jose G. Sibulo, and Ms. resources, for the CLUP is the basis of the city’s Zoning Ordinance. Marilyn Joven. Not only is the CLUP an essential element in socio-economic For Social Sector: the Department of Education, Culture and development but a potent planning tool as well. With it, planners can Sports – City Schools Division (DECS), the Naga Parochial School determine and forecast needs of the future and for generations to (NPS), University of Nueva Caceres (UNC), Ateneo de Naga come, thereby making public servants ably prepared for even the University (AdeNU), Colegio de Sta. Isabel (CSI), Bicol College of worst of scenarios. Arts and Trade (BCAT), -

Flood Flow Modelling Inthe Bicol River Basin

COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT ON HUMAN SETTLEMENTS AND NATURAL RESOURCE SYSTEMS ANALYSIS FLOOD FLOW MODELLING INTHE BICOL RIVER BASIN by Mac McKee Settlement and Resource Systems Analysis Clark University/Institute for Development Anthropology Cooperative Agreement (USAID) Clark University Institute for Development Anthropology International Development Program Suite 302, P.O. Box 818 950 Main Street 99 Collier Street Worcester. MA 01610 Binghamton, NY 13902 FLOOD FLOW MODELLING IN THE BICOL RIVER BASIN by Mac McKee for United States Agency for International Development, Manila and Bicol River Basin Development Program Settlement and Resource Systems Analysis Clark University/Institute for Development Anthropology Cooperacive Agreement (USAID) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION. .. .1 1.1 Statement of Problem 1.2 Purpose 2.0 OVERVIEW OF THE MODEL. 2.1 Equations of Cotinuity and Motion 2.1.1 Continuity 2.1.2 Motion 2.1.3 Finite Difference Approximations 2.1.3.1 River Schematization 2.1.3.2 Finite Difference Expression of Continuity 2.1.3.3 Finite Difference Expression of Motion 2.2 Modeling of Boundary Conditions 2.2.1 Tidal Elevations 2.2.2 Tributary Inflows 2.3 Modeling of Control Structures 2.3.1 Flapgate Discharges 2.3.2 Free-Overall Spillway Discharges 2.3.3 Spillway Discharges with Downstream Backwater 3.0 MODEL CALIBRATION . 8 3.1 Purpose of Calibration 3.2 Procedures Used in Calibration 3.3 Data Used in Calibration 3.4 Results of Calibration 4.0 PRODUCTION RUNS . 12 REFERENCES . 14 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 STATEMENT OF PROBLEM The Bicol River Basin located on the southern end of the island of Luzon, Philippines, annually experiences severe floods that result from the typhoons (see Map 1). -

Pres. Duterte Allocates P500 Million for Typhoon Nina Rehab in Bicol

October - December 2016 Vol. 25 No. 4 President Rodrigo LGU Sorsogon Duterte meets the local chief executives and selected wins P1million as farmers of Camarines Sur “Be Riceponsible” at the Provincial Capitol in Cadlan, Pili, Camarines Sur, advocacy champion three days after typhoon Nina ravaged Bicol. Photo The provincial government shows President Duterte of Sorsogon, Bicol’s lone entry consulting agriculture to the DA-Philippine Rice secretary Manny F. Piñol on Research Institute (PhilRice) DA’s rehabilitation funds. nationwide BeRiceponsible Search for Best Advocacy Campaign was adjudged as champion under the Provincial Government category and won P1 Million cash prize. Hazel V. Antonio, director Pres. Duterte allocates P500 million of the Be RICEponsible campaign led the awarding ceremony which was held at for typhoon Nina rehab in Bicol PhilRice in Nueva Ecija on by Emily B. Bordado (Please turn to page 15) Typhoon Nina devastated three Bicol provinces and wrought heavy damage on the agriculture sector. FULL FLEDGED. Final damage report shows that the number of Agriculture farmers affected from the province of Camarines Sur, Secretary Catanduanes and Albay is 86,735. Of this, 73,757 are rice Emmanuel farmers; 8,387 corn farmers and 4,002 are high value F. Piñol crop farmers. The value of production loss is estimated administered at over P5.1 billion. the oath of office to The total rice area affected planting anew. The assistance our beloved is 59,528.23 hectare; for corn will be in the form of palay Regional 12,727.17 hectare and for seeds to be distributed to the Executive high value crops including affected farmers. -

Nsm 2014 04.Pdf

SIEGLINDE FLORENCIO T. MONGOSO, JR. BORROMEO-BULAONG REUEL M. OLIVER Editor Editorial Consultants Vol. 6, No. 4 | October - December 2014 JASON B. NEOLA JOSE V. COLLERA Senior Writer XERES RAMON A. GAGERO A Quarterly Magazine of the SYLRANJELVIC C. VILLAFLOR City Government of Naga Photographers Bicol, Philippines RAFAEL RACSO V. VITAN Layout and Design ISSN 2094-9383 JOHN G. BONGAT ANSELMO B. MAÑO City Mayor Website Administrator NELSON S. LEGACION City Vice Mayor JOSE B. PEREZ This magazine is published ALLEN L. REONDANGA by the City Government of Naga, thru UAINT AND PAUL JOHN F. BARROSA the Ciy Publication Office and the Q Technical Advisers City Events, Protocol and ALLURING. With its Public Information Office, rooftops breezed by with editorial office at City Hall Compound, the cool morning sun, ALDO NIÑO I. RUIVIVAR J. Miranda Avenue, Naga City 4400 Naga, then known as MAUREEN S. ROJO Philippines Staff Assistants Nueva Caceres in the Tel: +63 54 472-2136 Spanish colonial times, Email: [email protected] Web: www.naga.gov.ph charms visitors with its mixture of an ancient cathedral (right), French-architectured seminary, a university that had been the oldest school for girls in the Far East (foreground, right of center), narrow avenues, and three plazas bounded by modern edifices and endless rows of food chains, department stores and shops, residential houses, inns and hotels. PHOTO BY PAI AGUILAR MAYOR’S MESSAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS Bullish on the 3 Future of Naga Rediscovering 33 Nick Joaquin CHRISTMAS PAGE Nagueña as 2014 35 Outstanding Teacher of the Philippines Kamundagan Festival 5 Bongat delivers 38 report on State of 10 Santa Fun Walk our Children The “Naga SMILES to the World” Naga hosts 1st 40 Regional PWD logo is composed of the two COVER STORY Summit baybayin characters, na and ga.