The Immaculate Reception

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

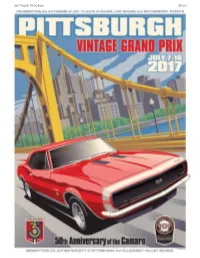

2017 Race Program $5.00

2017 RACE PROGRAM $5.00 2017 PITTSBURGH VINTAGE GRAND PRIX www.pvgp.org 2017 GRAND PRIX A Message from the PVGP .......................02 PVGP Executive Committee & Board of Directors ...04 Welcome from Pittsburgh Mayor Bill Peduto .......05 Presenting Sponsor - GPADF . ....................08 Sponsors and Partners ..........................08 Our Charities and Ambassadors ..................12 Poster Artist - Jim Zahniser .......................14 35 Years of Thrills ...............................16 Myron Cope’s Influence .........................18 Race Week Calendar ............................20 Make Your Grand Prix Dollars Go Farther ...........24 TWO RACE WEEKENDS Vintage Races at Schenley Park ...................26 Race Schedule ................................27 Schenley Park Maps ...........................30 Shuttle Buses & Parking ........................34 Race Entries .................................36 Recent Winners ...............................40 Legends of Schenley Park ......................41 Event Information .............................45 PVGP Historics at Pitt Race Complex ..............48 CONTENTS Race Schedule ................................50 Race Entries ..................................51 Recent Winners ..............................56 Pittsburgh International Race Complex. 57 CAR SHOWS International Car Show at Schenley Park ...........58 Sponsored Activities at Schenley Park .............62 Camaro Marque of the Year . 66 Studebaker Spotlight Car .......................72 Car Clubs and Car Shows ........................74 -

INDIANAPOLIS COLTS WEEKLY PRESS RELEASE Indiana Farm Bureau Football Center P.O

INDIANAPOLIS COLTS WEEKLY PRESS RELEASE Indiana Farm Bureau Football Center P.O. Box 535000 Indianapolis, IN 46253 www.colts.com REGULAR SEASON WEEK 6 INDIANAPOLIS COLTS (3-2) VS. NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (4-0) 8:30 P.M. EDT | SUNDAY, OCT. 18, 2015 | LUCAS OIL STADIUM COLTS HOST DEFENDING SUPER BOWL BROADCAST INFORMATION CHAMPION NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS TV coverage: NBC The Indianapolis Colts will host the New England Play-by-Play: Al Michaels Patriots on Sunday Night Football on NBC. Color Analyst: Cris Collinsworth Game time is set for 8:30 p.m. at Lucas Oil Sta- dium. Sideline: Michele Tafoya Radio coverage: WFNI & WLHK The matchup will mark the 75th all-time meeting between the teams in the regular season, with Play-by-Play: Bob Lamey the Patriots holding a 46-28 advantage. Color Analyst: Jim Sorgi Sideline: Matt Taylor Last week, the Colts defeated the Texans, 27- 20, on Thursday Night Football in Houston. The Radio coverage: Westwood One Sports victory gave the Colts their 16th consecutive win Colts Wide Receiver within the AFC South Division, which set a new Play-by-Play: Kevin Kugler Andre Johnson NFL record and is currently the longest active Color Analyst: James Lofton streak in the league. Quarterback Matt Hasselbeck started for the second consecutive INDIANAPOLIS COLTS 2015 SCHEDULE week and completed 18-of-29 passes for 213 yards and two touch- downs. Indianapolis got off to a quick 13-0 lead after kicker Adam PRESEASON (1-3) Vinatieri connected on two field goals and wide receiver Andre John- Day Date Opponent TV Time/Result son caught a touchdown. -

Alltconference Teams

ALL -CONFEREN C E TE A MS ALL -CONFEREN C E TE A MS First Team 1940 1947 1954 1961 Selections Only E Joe Blalock, CLEM E Bob Steckroth, W&M E Billy Hillen, WVU E Bill Gilgo, CIT E Paul Severin, UNC E Art Weiner, UNC E Tom Petty, VT E Andy Guida, GWU 1933 T Andy Fronczek, RIC T Chi Mills, VMI T Bruce Bosley, WVU T Gene Breen, VT E Red Negri, UVA T Tony Ruffa, Duke T Len Szafaryn, UNC T George Preas, VT T Bill Winter, WVU E Tom Rogers, Duke G Bill Faircloth, UNC G Knox Ramsey, W&M G Gene Lamone, WVU G Eric Erdossy, W&M T Ray Burger, UVA G Alex Winterspoon, Duke G Ed Royston, WFU G Webster Williams, FUR G Keith Melenyzer, WVU T Fred Crawford, Duke C Bob Barnett, Duke C Tommy Thompson, W&M C Chick Donaldson, WVU C Don Christman, RIC G Amos Bolen, W&L B Tony Gallovich, WFU B Jack Cloud, W&M B Dickie Beard, VT B Tom Campbell, FUR G George Barclay, UNC B Steve Lach, Duke B Fred Fogler Jr., Duke B Joe Marconi, WVU B Dick Drummond, GWU C Gene Wagner, UVA B Jim Lelanne, UNC B Lou Gambino, MD B Johnny Popson, FUR B Earley Eastburn, CIT B Al Casey, Va. Tech B Charlie Timmons, CLEM B Charlie Justice, UNC B Freddy Wyant, WVU B Earl Stoudt, RIC B Earl Clary, USC B Bob Cox, Duke 1941 1948 1955 1962 B Horace Hendrickson, Duke E Joe Blalock, CLEM E John O’Quinn, WFU E Walt Brodie, W&M E Charlie Brendle, CIT E Bob Gantt, Duke E Art Weiner, UNC E Paul Thompson, GWU E Gene Heeter, WVU 1934 T George Fritts, CLEM T Louis Allen, Duke T Bruce Bosley, WVU T John Sapinsky, W&M E Dave Thomas, VT T Mike Karmazin, Duke T Len Szafaryn, UNC T Bob Lusk, W&M T Bill Welsh, -

Sports Publishing Fall 2018

SPORTS PUBLISHING Fall 2018 Contact Information Editorial, Publicity, and Bookstore and Library Sales Field Sales Force Special Sales Distribution Elise Cannon Skyhorse Publishing, Inc. Two Rivers Distribution VP, Field Sales 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor Ingram Content Group LLC One Ingram Boulevard t: 510-809-3730 New York, NY 10018 e: [email protected] t: 212-643-6816 La Vergne, TN 37086 f: 212-643-6819 t: 866-400-5351 e: [email protected] Leslie Jobson e: [email protected] Field Sales Support Manager t: 510-809-3732 e: [email protected] International Sales Representatives United Kingdom, Ireland & Australia, New Zealand & India South Africa Canada Europe Shawn Abraham Peter Hyde Associates Thomas Allen & Son Ltd. General Inquiries: Manager, International Sales PO Box 2856 195 Allstate Parkway Ingram Publisher Services UK Ingram Publisher Services Intl Cape Town, 8000 Markham, ON 5th Floor 1400 Broadway, Suite 520 South Africa L3R 4T8 Canada 52–54 St John Street New York, NY, 10018 t: +27 21 447 5300 t: 800-387-4333 Clerkenwell t: 212-581-7839 f: +27 21 447 1430 f: 800-458-5504 London, EC1M 4HF e: shawn.abraham@ e: [email protected] e: [email protected] e: IPSUK_enquiries@ ingramcontent.com ingramcontent.co.uk India All Other Markets and Australia Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd. General International Enquiries Ordering Information: NewSouth Books 7th Floor, Infinity Tower C Ingram Publisher Services Intl Grantham Book Services Orders and Distribution DLF Cyber City, Phase - III 1400 Broadway, -

Mountaineers in the Pros

MOUNTAINEERS IN THE PROS Name (Years Lettered at WVU) Team/League Years Stedman BAILEY ALEXANDER, ROBERT (77-78-79-80) Los Angeles Rams (NFL) 1981-83 Los Angeles Express (USFL) 1985 ANDERSON, WILLIAM (43) Boston Yanks (NFL) 1945 ATTY, ALEXANDER (36-37-38) New York Giants (NFL) 1948 AUSTIN, TAVON (2009-10-11-12) St. Louis Rams (NFL) 2013 BAILEY, RUSSELL (15-16-17-19) Akron Pros (APFA) 1920-21 BAILEY, STEDMAN (10-11-12) St. Louis Rams (NFL) 2013 BAISI, ALBERT (37-38-39) Chicago Bears (NFL) 1940-41,46 Philadelphia Eagles (NFL) 1947 BAKER, MIKE (90-91-93) St. Louis Stampede (AFL) 1996 Albany Firebirds (AFL) 1997 Name (Years Lettered at WVU) Name (Years Lettered at WVU) Grand Rapids Rampage (AFL) 1998-2002 Team/League Years Team/League Years BARBER, KANTROY (94-95) BRAXTON, JIM (68-69-70) CAMPBELL, TODD (79-80-81-82) New England Patriots (NFL) 1996 Buffalo Bills (NFL) 1971-78 Arizona Wranglers (USFL) 1983 Carolina Panthers (NFL) 1997 Miami Dolphins (NFL) 1978 Miami Dolphins (NFL) 1998-99 CAPERS, SELVISH (2005-06-07-08) BREWSTER, WALTER (27-28) New York Giants (NFL) 2012 BARCLAY, DON (2008-09-10-11C) Buffalo Bisons (NFL) 1929 Green Bay Packers 2012-13 CARLISS, JOHN (38-39-40) BRIGGS, TOM (91-92) Richmond Rebels (DFL) 1941 BARNUM, PETE (22-23-25-26) Anaheim Piranhas (AFL) 1997 Columbus Tigers (NFL) 1926 CLARKE, HARRY (37-38-39) Portland Forest Dragons (AFL) 1997-99 Chicago Bears (NFL) 1940-43 BARROWS, SCOTT (82-83-84) Oklahoma Wranglers (AFL) 2000-01 San Diego Bombers (PCFL) 1945 Detroit Lions (NFL) 1986-87 Dallas Desperados (AFL) 2002-03 Los -

Franco Harris President, Super Bakery Former Steeler & Pro Football Hall

Franco Harris President, Super Bakery Former Steeler & Pro Football Hall of Famer Franco Harris is well known for his outstanding career in the National Football League, one so productive that it earned him a 1990 induction into The Pro Football Hall of Fame. He also was inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame in 2011. During his years with the Pittsburgh Steelers, Harris set the standard for NFL running backs - big, fast and agile with explosive cutback ability. He established many team and league records, played in nine Pro Bowls, and led the Steelers’ charge to four Super Bowl victories. Franco was named MVP of Super Bowl IX. His “Immaculate Reception” in the final seconds of the 1972 AFC playoff game against the Oakland Raiders is considered to be the greatest individual play in NFL history. After football, Harris applied himself to his college degree in Food Service and Administration. He started out in the early 1980’s with a small distribution company called Franco’s All Naturèl, focusing on high quality, natural products. This is where and how Harris learned the business, driving thousands of miles, meeting with potential customers, c-store chains and distributors. He warehoused, sold, promoted and sometimes even delivered Franco’s FROZEFRUIT and his other all-natural products. In 1990 Harris established Super Bakery with the goal of making it The Leader in Bakery Nutrition. Super Donuts and Super Buns are made with no artificial flavors, colors, or preservatives and are fortified with NutriDough, a special dough of Minerals, Vitamins and Protein. Super Donuts and Super Buns are sold to school systems across America, providing MVP Nutrition! to millions of students each year. -

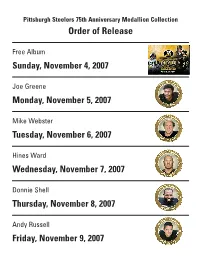

PSL Medallion Release Order.V1

Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Free Album Sunday, November 4, 2007 Joe Greene Monday, November 5, 2007 Mike Webster Tuesday, November 6, 2007 Hines Ward Wednesday, November 7, 2007 Donnie Shell Thursday, November 8, 2007 Andy Russell Friday, November 9, 2007 Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Carnell Lake Saturday, November 10, 2007 Terry Bradshaw Sunday, November 11, 2007 Casey Hampton Monday, November 12, 2007 Rocky Bleier Tuesday, November 13, 2007 Greg Lloyd Wednesday, November 14, 2007 Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Elbie Nickel Thursday, November 15, 2007 Rod Woodson Friday, November 16, 2007 Larry Brown Saturday, November 17, 2007 Lynn Swann Sunday, November 18, 2007 Dermontti Dawson Monday, November 19, 2007 Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Bobby Walden Tuesday, November 20, 2007 Joey Porter Wednesday, November 21, 2007 Jack Ham Thursday, November 22, 2007 Tunch Ilkin Friday, November 23, 2007 Gary Anderson Saturday, November 24, 2007 Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Franco Harris Sunday, November 25, 2007 Commemorative Medallion Monday, November 26, 2007 L.C. Greenwood Tuesday, November 27, 2007 Jack Butler Wednesday, November 28, 2007 Jon Kolb Thursday, November 29, 2007 Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Dwight White Friday, November 30, 2007 Ernie Stautner Saturday, December 1, 2007 Jerome Bettis Sunday, December 2, 2007 Alan Faneca Monday, December 3, 2007 Bennie Cunningham Tuesday, December 4, 2007 Pittsburgh Steelers 75th Anniversary Medallion Collection Order of Release Troy Polamalu Wednesday, December 5, 2007 Mel Blount Thursday, December 6, 2007 John Stallworth Friday, December 7, 2007 Bonus Coupon Saturday, December 8, 2007 BONUS COUPON for any previously released medallion Here is a chance to collect any medallion you may have missed so far. -

Photo Courtesy of the Pittsburgh Steelers

Photo Courtesy of the Pittsburgh Steelers 1 IMCD is a global leader in the sales, marketing and distribution of specialty chemicals and ingredients for the Industrial and Life Science markets, delivering innovative solutions that exceed customer expectations. Representing market leading global chemical companies enables us to offer a comprehensive and complementary product portfolio. We bring added value and growth to both our customers and principal partners across the world through our technical, marketing and supply chain expertise. With over 1800 high-caliber professionals in more than 40 countries on 6 continents, IMCD offers a unique combination of local understanding backed by an impressive International infrastructure. To find out how our expertise can bring value to your business, please visit www.imcdus.com 2 Welcome to Pittsburgh Chemical Day 2 017 On behalf of the Joint Chemical Group of Pittsburgh and our volunteer planning committee, we welcome you to the 50th annual Pittsburgh Chemical Day conference. This year we are celebrating 50 years of coming together to network, learn, and grow in an ever-changing Chemical Industry. We have designed our program to highlight the past while IMCD is a global leader in the sales, marketing and distribution looking towards the future markets, trends, and regulations that of specialty chemicals and ingredients for the Industrial and Life will impact us in the years to come. Science markets, delivering innovative solutions that exceed customer expectations. Representing market leading global Our goal is to utilize our new venue, Heinz Field, to help chemical companies enables us to offer a comprehensive and celebrate our incredible history and city, while providing you an complementary product portfolio. -

1963 San Diego Chargers

The Professional Football Researchers Association The AFL’s First Super Team Pro Football Insiders Debate Whether the AFL Champion San Diego Chargers Could Have Beaten the Bears in a 1963 Super Bowl By Ed Gruver It's an impossible question, but one that continues to intrigue until January 12, 1969, when Joe Namath quarterbacked the members of the 1963 AFL champion San Diego Chargers. upstart New York Jets to a stunning 16-7 victory over the heavily- favored Baltimore Colts in Super Bowl III, that the AFL earned its If the Super Bowl had started with the 1963 season instead of first championship game win over the NFL. Even so, it wasn't until 1966, could the Chargers have beaten the NFL champion Chicago Len Dawson led the Kansas City Chiefs to a similar win one year Bears? later over the Minnesota Vikings in the fourth and final Super Bowl between the AFL and NFL that the AFL finally got its share of "I've argued that for years and years," says Sid Gillman, who respect from both the NFL and football fans. coached the 1963 Chargers. "We had one of the great teams in pro football history, and I think we would have matched up pretty well Those who know the AFL however, believe that the 163 Chargers, with the NFL. We had great speed and talent, and I think at that rather than the '68 Jets, might have gone down in history as the time, the NFL really underestimated the talent we had." first AFL team to win a Super Bowl. -

17 Finalists for Hall of Fame Election

For Immediate Release For More Information, Contact: January 10, 2007 Joe Horrigan at (330) 456-8207 17 FINALISTS FOR HALL OF FAME ELECTION Paul Tagliabue, Thurman Thomas, Michael Irvin, and Bruce Matthews are among the 17 finalists that will be considered for election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame when the Hall’s Board of Selectors meets in Miami, Florida on Saturday, February 3, 2007. Joining these four finalists, are 11 other modern-era players and two players nominated earlier by the Hall of Fame’s Senior Committee. The Senior Committee nominees, announced in August 2006, are former Cleveland Browns guard Gene Hickerson and Detroit Lions tight end Charlie Sanders. The other modern-era player finalists include defensive ends Fred Dean and Richard Dent; guards Russ Grimm and Bob Kuechenberg; punter Ray Guy; wide receivers Art Monk and Andre Reed; linebackers Derrick Thomas and Andre Tippett; cornerback Roger Wehrli; and tackle Gary Zimmerman. To be elected, a finalist must receive a minimum positive vote of 80 percent. Listed alphabetically, the 17 finalists with their positions, teams, and years active follow: Fred Dean – Defensive End – 1975-1981 San Diego Chargers, 1981- 1985 San Francisco 49ers Richard Dent – Defensive End – 1983-1993, 1995 Chicago Bears, 1994 San Francisco 49ers, 1996 Indianapolis Colts, 1997 Philadelphia Eagles Russ Grimm – Guard – 1981-1991 Washington Redskins Ray Guy – Punter – 1973-1986 Oakland/Los Angeles Raiders Gene Hickerson – Guard – 1958-1973 Cleveland Browns Michael Irvin – Wide Receiver – 1988-1999 -

1.) What Was the Original Name of the Pittsburgh Steelers? B. the Pirates

1.) What was the original name of the Pittsburgh Steelers? B. The Pirates The Pittsburgh football franchise was founded by Art Rooney on July 7, 1933. When he chose the name for his team, he followed the customary practice around the National Football League of naming the football team the same as the baseball team if there was already a baseball team established in the city. So the professional football team was originally called the Pittsburgh Pirates. 2.) How many Pittsburgh Steelers have had their picture on a Wheaties Box? C. 13 Since Wheaties boxes have started featuring professional athletes and other famous people, 13 Steelers have had their pictures on the box. These players are Kevin Greene, Greg Lloyd, Neil O'Donnell, Yancey Thigpen, Bam Morris, Franco Harris, Joe Greene, Terry Bradshaw, Barry Foster, Merril Hoge, Carnell Lake, Bobby Layne, and Rod Woodson. 3.) How did sportscaster Curt Gowdy refer to the Immaculate Reception, which happened two days before Christmas? Watch video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GMuUBZ_DAeM A. The Miracle of All Miracles “You talk about Christmas miracles. Here's the miracle of all miracles. Watch this one now. Bradshaw is lucky to even get rid of the ball! He shoots it out. Jack Tatum deflects it right into the hands of Harris. And he sets off. And the big 230-pound rookie slipped away from Warren and scored.” —Sportscaster Curt Gowdy, describing an instant replay of the play on NBC 4.) URA Acting Executive Director Robert Rubinstein holds what football record at Churchill Area High School? B. -

Pioneer Las Vegas Bowl Sees Its Allotment of Public Tickets Gone Nearly a Month Earlier Than the Previous Record Set in 2006 to Mark a Third-Straight Sellout

LAS VEGAS BOWL 2016 MEDIA GUIDE A UNIQUE BLEND OF EXCITEMENT ian attraction at Bellagio. The world-famous Fountains of Bellagio will speak to your heart as opera, classical and whimsical musical selections are carefully choreo- graphed with the movements of more than 1,000 water- emitting devices. Next stop: Paris. Take an elevator ride to the observation deck atop the 50-story replica of the Eiffel Tower at Paris Las Vegas for a panoramic view of the Las Vegas Valley. For decades, Las Vegas has occupied a singular place in America’s cultural spectrum. Showgirls and neon lights are some of the most familiar emblems of Las Vegas’ culture, but they are only part of the story. In recent years, Las Vegas has secured its place on the cultural map. Visitors can immerse themselves in the cultural offerings that are unique to the destination, de- livering a well-rounded dose of art and culture. Swiss artist Ugo Rondinone’s colorful, public artwork Seven Magic Mountains is a two-year exhibition located in the desert outside of Las Vegas, which features seven towering dayglow totems comprised of painted, locally- sourced boulders. Each “mountain” is over 30 feet high to exhibit the presence of color and expression in the There are countless “excuses” for making a trip to Las feet, 2-story welcome center features indoor and out- Vegas, from the amazing entertainment, to the world- door observation decks, meetings and event space and desert of the Ivanpah Valley. class dining, shopping and golf, to the sizzling nightlife much more. Creating a city-wide art gallery, artists from around that only Vegas delivers.