Tripwire12 Tripwire 12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Look at 'Fishy Drag' and Androgynous Fashion: Exploring the Border

This is a repository copy of A look at ‘fishy drag’ and androgynous fashion: Exploring the border spaces beyond gender-normative deviance for the straight, cisgendered woman. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/121041/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Willson, JM orcid.org/0000-0002-1988-1683 and McCartney, N (2017) A look at ‘fishy drag’ and androgynous fashion: Exploring the border spaces beyond gender-normative deviance for the straight, cisgendered woman. Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty, 8 (1). pp. 99-122. ISSN 2040-4417 https://doi.org/10.1386/csfb.8.1.99_1 (c) 2017, Intellect Ltd. This is an author produced version of a paper published in Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 JACKI WILLSON University of Leeds NICOLA McCARTNEY University of the Arts, London and University of London A look at ‘fishy drag’ and androgynous fashion: Exploring the border spaces beyond gender-normative deviance for the straight, cisgendered woman Abstract This article seeks to re-explore and critique the current trend of androgyny in fashion and popular culture and the potential it may hold for gender deviant dress and politics. -

Title of Dissertation

SETTING UP CAMP: IDENTIFYING CAMP THROUGH THEME AND STRUCTURE A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Michael T. Schuyler January, 2011 Examining Committee Members: Cornelius B. Pratt, Advisory Chair, Strategic Communication John A. Lent, Broadcasting, Telecommunications & Mass Media Paul Swann, Film & Media Arts Roberta Sloan, External Member, Theater i © Copyright 2010 by Michael T. Schuyler All Rights Reserved ii ABSTRACT Camp scholarship remains vague. While academics don’t shy away from writing about this form, most exemplify it more than define it. Some even refuse to define it altogether, arguing that any such attempt causes more problems than it solves. So, I ask the question, can we define camp via its structure, theme and character types? After all, we can do so for most other genres, such as the slasher film, the situation comedy or even the country song; therefore, if camp relies upon identifiable character types and proliferates the same theme repeatedly, then, it exists as a narrative system. In exploring this, I find that, as a narrative system, though, camp doesn’t add to the dominant discursive system. Rather, it exists in opposition to it, for camp disseminates the theme that those outside of heteronormativity and acceptability triumph not in spite of but because of what makes them “different,” “othered” or “marginalized.” Camp takes many forms. So, to demonstrate its reliance upon a certain structure, stock character types and a specific theme, I look at the overlaps between seemingly disperate examples of this phenomenon. -

Download PDF Datastream

Claiming History, Claiming Rights: Queer Discourses of History and Politics By Evangelia Mazaris B.A., Vassar College, 1998 A.M., Brown University, 2005 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of American Civilization at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Evangelia Mazaris This dissertation by Evangelia Mazaris is accepted in its present form by the Department of American Civilization as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date: ________________ ______________________________ Ralph E. Rodriguez, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date: ________________ ______________________________ Karen Krahulik, Reader Date: ________________ ______________________________ Steven Lubar, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date: ________________ ______________________________ Sheila Bonde, Dean of the Graduate School iii CURRICULUM VITAE Evangelia Mazaris was born in Wilmington, Delaware on September 21, 1976. She received her B.A. in English from Vassar College in 1998. Mazaris completed her A.M. in Museum Studies/American Civilization at Brown University in 2005. Mazaris was a Jacob Javits Fellow through the United States Department of Education (2004 – 2009). Mazaris is the author of “Public Transgressions: the Reverend Phebe Hanaford and the „Minister‟s Wife‟,” published in the anthology Tribades, Tommies and Transgressives: Lesbian Histories, Volume I (Cambridge Scholars Press, 2008). She also published the article “Evidence of Things Not Seen: Greater Light as Faith Manifested,” in Historic Nantucket (Winter 2001). She has presented her work at numerous professional conferences, including the American Studies Association (2008), the New England American Studies Association (2007), the National Council on Public History (2009), and the University College Dublin‟s Historicizing the Lesbian Conference (2006). -

Kiyan Williams Interviewer: Esperanza Santos Date

Queer Newark Oral History Project Interviewee: Kiyan Williams Interviewer: Esperanza Santos Date: October 11, 2019 Location: Via phone call from Rutgers-Newark and Richmond, Virginia Vetted by: Cristell Cedeno Date: November 24, 2019 Interviewer: Today is October 11th, 2019. My name is Esperanza Santos, and I'm interviewing Kiyan Williams at Newark—at Rutgers Newark while they are in Richmond, Virginia, for the Queer Newark Oral History Project. Hi Kiyan. Interviewee: Hello. Interviewer: Hi. Well, thank you so much for taking time out to be with me today. Interviewee: It's really a pleasure. I'm so excited that we found the time to connect. Interviewer: Right. We've been emailing back and forth for a minute, but we made it work. Interviewee: Totally. Interviewer: Tell me, just to start off the conversation, when and where were you born? Interviewee: I was born in Newark, New Jersey. Interviewer: Can you tell me your birthday if that's okay? Interviewee: Yeah, I was born on March 6th, 1991, at UMDNJ. Interviewer: Does that make you an Aquarius or an Aries? Interviewee: It makes me a Pisces. Interviewer: Oh, it makes you a Pisces. Okay. Who raised you when you were growing up? Interviewee: I was raised by—primarily by my mother and also by my grandmother. Interviewer: Okay. When your grandma and your mom were raising you, did you grow up in one place, or did y'all move around a lot? Interviewee: I mostly grew up in East Orange, in North New Jersey. I spent all of my childhood and my teenage years between Newark and East, which are adjacent cities that are right next to each other. -

Shame and the Narration of Subjectivity in Contemporary U.S.-Caribbean Fiction

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository BLUSHING TO BE: SHAME AND THE NARRATION OF SUBJECTIVITY IN CONTEMPORARY U.S.-CARIBBEAN FICTION María Celina Bortolotto A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: Professor María DeGuzmán Professor Tanya Shields Professor Alice Kuzniar Professor Rosa Perelmuter Professor Rebecka Rutledge-Fisher © 2008 María Celina Bortolotto ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT BLUSHING TO BE: Shame and the Narration of Subjectivity in Contemporary U.S.- Caribbean Fiction (Under the direction of Dr. María DeGuzmán and Dr. Tanya Shields) This study engages shame/affect (mostly psychoanalytical) theory in an interdisciplinary approach that traces narratives of resistance from “invisible” subjectivities within dominant U.S.- Caribbean discourses in contemporary fictional texts. It consists of an introduction, four chapters, and a conclusion. The introduction provides a precise theoretical background for the study. It defines key terms making a detailed reference to the prevailing discourses in the Caribbean and the U.S. The first chapter reveals examples in the fiction of the complex relationship between shame and visibility/invisibility as embodied in the figure of the secret/closet, in relation to prevailing identity discourses. The second chapter analyzes the relationship of shame with narcissistic and masochistic tendencies as presented in the fiction, evaluating the weight of narratives in the dynamics of such disorders. -

List of All Porno Film Studio in the Word

LIST OF ALL PORNO FILM STUDIO IN THE WORD 007 Erections 18videoz.com 2chickssametime.com 40inchplus.com 1 Distribution 18virginsex.com 2girls1camera.com 40ozbounce.com 1 Pass For All Sites 18WheelerFilms.com 2hotstuds Video 40somethingmag.com 10% Productions 18yearsold.com 2M Filmes 413 Productions 10/9 Productions 1by-day.com 3-Vision 42nd Street Pete VOD 100 Percent Freaky Amateurs 1R Media 3-wayporn.com 4NK8 Studios 1000 Productions 1st Choice 30minutesoftorment.com 4Reel Productions 1000facials.com 1st Showcase Studios 310 XXX 50plusmilfs.com 100livresmouillees.com 1st Strike 360solos.com 60plusmilfs.com 11EEE Productions 21 Naturals 3D Club 666 130 C Street Corporation 21 Sextury 3d Fantasy Film 6666 Productions 18 Carat 21 Sextury Boys 3dxstar.com 69 Distretto Italia 18 Magazine 21eroticanal.21naturals.com 3MD Productions 69 Entertainment 18 Today 21footart.com 3rd Degree 6969 Entertainment 18 West Studios 21naturals.com 3rd World Kink 7Days 1800DialADick.com 21roles.com 3X Film Production 7th Street Video 18AndUpStuds.com 21sextreme.com 3X Studios 80Gays 18eighteen.com 21sextury Network 4 Play Entertainment 818 XXX 18onlygirls.com 21sextury.com 4 You Only Entertainment 8cherry8girl8 18teen 247 Video Inc 4-Play Video 8Teen Boy 8Teen Plus Aardvark Video Absolute Gonzo Acerockwood.com 8teenboy.com Aaron Enterprises Absolute Jewel Acheron Video 8thstreetlatinas.com Aaron Lawrence Entertainment Absolute Video Acid Rain 9190 Xtreme Aaron Star Absolute XXX ACJC Video 97% Amateurs AB Film Abstract Random Productions Action Management 999 -

French Fliers Smash Long Distance Mark

•'* ■ J VOL. LIL, NO. 263. (tlaselfled AdwHstag on Paft 10) MANCHESTER, CONN., MONDAY, AUGUST 7,1983. TWELVE PAGES PRICE THREE CENTS A "Gripping** Moment STATE MILK BOARD 1 flOMDREDS PA Y FRENCH FLIERS SMASH IS ASKED TO RESIGN i LAST TRIBUTE TO C E . HOUSE LONG DISTANCE MARK ludepeodeiit Dealers of NINE MEET DEATH Center Chnrch b Crowded Rossi and Codos, Still Up Greater Hartford Says OVER THE WEEK-END Lonf Before Service for Miners Ignore Truce;. After Trarefing 5,340 Control Body is Trying to Fnneral of Dean of Town’s Refuse to go to Work M3es—Are Now Heidigg Wipe Ont Small Dealers. Shipwreck on Sonnd— Han Business Men. Kills and S e l f - Brownsville, Pa„ Aug. 7.—(A P)^ ’The strikers, who say they waht for Rayak, Spria— Had BULLETD^: —Ignoring a truco effected by more time in which to study terms Hartford, Aug. 7.—(AP)— Tbe townspeople of Manchester Piresldent Roosevelt, thousands of of the agreement, had their picket With tho threat of a milk strike Other Cases Reported. turaell out hundreds late (his ndnert In the vast coal fields of army in the field, but most ^cket Maeii Tronble WiA Leak- mutterliig In the background, afternoon to pay final homage to SoutL.western Pennsylvania refused lines dwindled after nc resumption developments In Ihe state's milk to go back to work today. wa< attempted. one of its outstanding and most re m g O B P ^ sitaation eonttnned rapidly this (By Associated Press) Hera ant. there, a mine re-opened The last mine operating in Fay m orning. -

Tideway's Public Art Strategy

PUBLIC ART STRATEGY ART ON THE TIDEWAY: TURNING TO FACE THE RIVER Contemporary Culture Liquid History | 1 Foreword In the mid-nineteenth century my great great grandfather, Joseph Bazalgette, devised London’s sewage and waste water system to tackle the cholera that was carried by a grossly polluted Thames. We affectionately call him ‘The Drain Brain’. His system’s success means it only now needs updating, 150 years on, when the city is four times the size. The need today may seem less obvious but without it our metropolis can’t continue to function as a safe, growing place to live and work. The Thames Tideway Tunnel is a grand, ambitious project. It will create new public amenities along the river. Challenging artists to bring all this to life celebrates the project while sharpening our sense of place. Just as the art, architecture and design of the Victorian Embankments and pumping stations expressed the spirit of that age. I am delighted that Tideway has launched a Public Art Strategy and Art Programme. The strong link between the Public Art and the Heritage Interpretation Strategies fuses the power of heritage and contemporary art. The artists will have rich themes to build on: the River Thames’s ecology, shared public space, our personal and community identities as well as a nod to the city’s changing fabric. Even during construction, hoardings created by artists and school children will challenge and delight. I’m a fervent believer in the power of arts and culture to improve our quality of life. This is what will happen here, both above and below ground. -

Toward a FIERCE Nomadology: Contesting Queer Geographies on the Christopher Street Pier1

Toward a FIERCE Nomadology: Contesting Queer Geographies on the Christopher Street Pier1 RACHEL LOEWEN WALKER Figure 1: Richard Renaldi (photographer), “Youth on the pier,” Pier 45-1, 2005.2 I. Introduction My intention has been to convey the unique character of this urban space as well as the faces which populate it: dog walkers and joggers, drag queens and dropouts, muscle boys on roller blades, homeless veterans, Stonewall survivors, elderly couples out for a Sunday stroll, sunbathers, and curious tourists – black and white, rich and poor, gay and straight, and every category in between (Richard Renaldi, regarding his photos of the community of the Christopher Street Pier, NYC). PhaenEx 6, no. 1 (spring/summer 2011): 90-120 © 2011 Rachel Loewen Walker - 91 - Rachel Loewen Walker As non-native of New York, I had heard about the Christopher Street Pier (Pier 45) by way of folklore and word-of-mouth, and though I knew little about its politics, it held an interest for me as an important part of New York‟s gay and lesbian rights movement. Along with the Pier, names such as the “Stonewall Inn,” “Christopher Street,” and “Greenwich Village” are all part of the cultural discourse that make up gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender histories in North America. However, as an unsuspecting tourist in June of 2006, I was surprised to find, in place of Pier 45, the pristine Hudson River Park with its manicured lawns, a concession booth, and a picture-perfect fountain—a glaring contradiction to what I expected from the site. Later, I had the opportunity to meet Rickke Mananzala, then co-director of FIERCE—Fabulous Independent Educated Radicals for Community Empowerment—who explained to me that Pier 45 had been redeveloped in 2003 in a municipal effort to revitalize the space as a city park for public use. -

United States Bankruptcy Court Southern District of Georgia

Case: 09-40805-LWD Doc#:162 Filed:07/06/09 Page:1 of 114 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA In re TITLEMAX HOLDINGS, LLC Debtor Case No. 09-40805 Chapter 11 SUMMARY OF SCHEDULES Indicate as to each schedule whether that schedule is attached and state the number of pages in each. Report the totals from Schedules A, B, D, E, F, I, and J in the boxes provided. Add the amounts from Schedules A and B to determine the total amount of the debtor's assets. Add the amounts from Schedules D, E, and F to determine the total amount of the debtor's liabilities. ATTACHED NAME OF SCHEDULE (YES/NO) NO. OF SHEETS ASSETS LIABILITIES OTHER A - Real Property Yes 1 B - Personal Property Yes 4 $10,127,693.67 C - Property Claimed No As Exempt D - Creditors Holding Yes 1 $164,000,000.00 Secured Claims E - Creditors Holding Unsecured Yes 3 Priority Claims F - Creditors Holding Unsecured Yes 1 $4,000,000.00 Nonpriority Claims G - Executory Contracts and Yes 100 Unexpired Leases H - Codebtors Yes 2 I - Current Income of Individual Debtor(s) No J - Current Expenditures of No Individual Debtor(s) TOTAL 112 $10,127,693.67 $168,000,000.00 Case: 09-40805-LWD Doc#:162 Filed:07/06/09 Page:2 of 114 In re TITLEMAX HOLDINGS, LLC Case No. 09-40805 Debtor (if known) SCHEDULE A - REAL PROPERTY Except as directed below, list all real property in which the debtor has any legal, equitable, or future interest, including all property owned as a cotenant, community property, or in which the debtor has a life estate. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Reading RuPaul's Drag Race: Queer Memory, Camp Capitalism, and RuPaul's Drag Empire Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0245q9h9 Author Schottmiller, Carl Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reading RuPaul’s Drag Race: Queer Memory, Camp Capitalism, and RuPaul’s Drag Empire A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Carl Douglas Schottmiller 2017 © Copyright by Carl Douglas Schottmiller 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Reading RuPaul’s Drag Race: Queer Memory, Camp Capitalism, and RuPaul’s Drag Empire by Carl Douglas Schottmiller Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor David H Gere, Chair This dissertation undertakes an interdisciplinary study of the competitive reality television show RuPaul’s Drag Race, drawing upon approaches and perspectives from LGBT Studies, Media Studies, Gender Studies, Cultural Studies, and Performance Studies. Hosted by veteran drag performer RuPaul, Drag Race features drag queen entertainers vying for the title of “America’s Next Drag Superstar.” Since premiering in 2009, the show has become a queer cultural phenomenon that successfully commodifies and markets Camp and drag performance to television audiences at heretofore unprecedented levels. Over its nine seasons, the show has provided more than 100 drag queen artists with a platform to showcase their talents, and the Drag Race franchise has expanded to include multiple television series and interactive live events. The RuPaul’s Drag Race phenomenon provides researchers with invaluable opportunities not only to consider the function of drag in the 21st Century, but also to explore the cultural and economic ramifications of this reality television franchise. -

View Entire Issue As

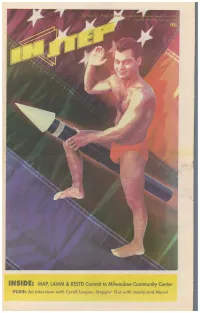

MINENNIMMIMMIN. Miler t•J:: e(Ild Filiri ii/111/C1/i r June 26, 1997 • Vd. k, I FREE INSIDE: MAP, LAMM & BESTD Commit to Milwaukee Community Center PLUS: An interview with Cyndi Lauper, Steppin' Out with Jamie and More! VOL. XIV, ISSUE XIII • JUNE 26, 1997 NEWS Community Center Gains Support 5 Religious Right Boycotts Disney 6 In Step Newsmagazine AIDS Debate Highlights Differences 7 1661 N. Water Street, Suite 411 Milwaukee, WI 53202 DEPARTMENTS (414) 278-7840 voice • (414) 278-5868 fax Group Notes 10 INSTEPWI@AOLCOM Opinion 14 Letters 15 ISSN# 1045-2435 The Arts 20 Ronald F. Geiman The Calendar 26 founder The Classies 31 The Guide 33 Jorge L. Cabal president William Attewell FEATURES editor-in-chief Cyndi Lauper Interview by Tim Nasson 15 New York, New York Travel Feature by Paul Hoffman 25 Jorge L.Cabal arts editor COLUMNS AND OPINION Manuel Kortright Tribal Talk by Ron Geiman 14 calendar editor Queer Science by Simon LeVey 27 John Quinlan Out of the Stars Horoscope by Charlene Lichtenstien 29 Madison Bureau Outings 30 Keepin' In Step by Jamie Taylor 30 Keith Clark, Ron Geiman, Ed Grover, Kevin Isom, Jamakaya, Owen Keehnen, Christopher Krimmer, Jim W. Lautenbach, Charlene Lichtenstein, Marvin Liebman, Cheryl Myers, Richard Mohr, Dale Reynolds, Shelly Roberts, Jamie Taylor, Rex Wockner, Arlene Zarembka, Yvonne Zipter contributing writers IN STEP MAGAZINE OFFICE HOURS: James Taylor Our offices are open to the public from photographer 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday through Friday at: Robert Arnold, Paul Berge cartoonists The Northern Lights Building 1661 North Water Street, Suite 411 Wells Ink art direction and ad design Milwaukee, WI 53202 Publication of the name, photograph or other likeness of any person or organization in In Step Newsmagazine is not to be construed as any indication of the sexual, religious or political orientation, practice or beliefs of such person or members of such organiza- tions.