Trashy Tendencies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Are We There Yet?

ARE WE THERE YET? Study Room Guide on Live Art and Feminism Live Art Development Agency INDEX 1. Introduction 2. Lois interviews Lois 3. Why Bodies? 4. How We Did It 5. Mapping Feminism 6. Resources 7. Acknowledgements INTRODUCTION Welcome to this Study Guide on Live Art and Feminism curated by Lois Weaver in collaboration with PhD candidate Eleanor Roberts and the Live Art Development Agency. Existing both in printed form and as an online resource, this multi-layered, multi-voiced Guide is a key component of LADA’s Restock Rethink Reflect project on Live Art and Feminism. Restock, Rethink, Reflect is an ongoing series of initiatives for, and about, artists who working with issues of identity politics and cultural difference in radical ways, and which aims to map and mark the impact of art to these issues, whilst supporting future generations of artists through specialized professional development, resources, events and publications. Following the first two Restock, Rethink, Reflect projects on Race (2006-08) and Disability (2009- 12), Restock, Rethink, Reflect Three (2013-15) is on Feminism – on the role of performance in feminist histories and the contribution of artists to discourses around contemporary gender politics. Restock, Rethink, Reflect Three has involved collaborations with UK and European partners on programming, publishing and archival projects, including a LADA curated programme, Just Like a Woman, for City of Women Festival, Slovenia in 2013, the co-publication of re.act.feminism – a performing archive in 2014, and the Fem Fresh platform for emerging feminist practices with Queen Mary University of London. Central to Restock, Rethink, Reflect Three has been a research, dialogue and mapping project led by Lois Weaver and supported by a CreativeWorks grant. -

Not Another Trash Tournament Written by Eliza Grames, Melanie Keating, Virginia Ruiz, Joe Nutter, and Rhea Nelson

Not Another Trash Tournament Written by Eliza Grames, Melanie Keating, Virginia Ruiz, Joe Nutter, and Rhea Nelson PACKET ONE 1. This character’s coach says that although it “takes all kinds to build a freeway” he is not equipped for this character’s kind of weirdness close the playoffs. This character lost his virginity to the homecoming queen and the prom queen at the same time and says he’ll be(*) “scoring more than baskets” at an away game and ends up in a teacher’s room wearing a thong which inspires the entire basketball team to start wearing them at practice. When Carrie brags about dating this character, Heather, played by Ashanti, hits her in the back of the head with a volleyball before Brittany Snow’s character breaks up the fight. Four girls team up to get back at this high school basketball star for dating all of them at once. For 10 points, name this character who “must die.” ANSWER: John Tucker [accept either] 2. The hosts of this series that premiered in 2003 once crafted a combat robot named Blendo, and one of those men served as a guest judge on the 2016 season of BattleBots. After accidentally shooting a penny into a fluorescent light on one episode of this show, its cast had to be evacuated due to mercury vapor. On a “Viewers’ Special” episode of this show, its hosts(*) attempted to sneeze with their eyes open, before firing cigarette butts from a rifle. This show’s hosts produced the short-lived series Unchained Reaction, which also aired on the Discovery Channel. -

Unobtainium-Vol-1.Pdf

Unobtainium [noun] - that which cannot be obtained through the usual channels of commerce Boo-Hooray is proud to present Unobtainium, Vol. 1. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We invite you to our space in Manhattan’s Chinatown, where we encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections by appointment or chance. Please direct all inquiries to Daylon ([email protected]). Terms: Usual. Not onerous. All items subject to prior sale. Payment may be made via check, credit card, wire transfer or PayPal. Institutions may be billed accordingly. Shipping is additional and will be billed at cost. Returns will be accepted for any reason within a week of receipt. Please provide advance notice of the return. Please contact us for complete inventories for any and all collections. The Flash, 5 Issues Charles Gatewood, ed. New York and Woodstock: The Flash, 1976-1979. Sizes vary slightly, all at or under 11 ¼ x 16 in. folio. Unpaginated. Each issue in very good condition, minor edgewear. Issues include Vol. 1 no. 1 [not numbered], Vol. 1 no. 4 [not numbered], Vol. 1 Issue 5, Vol. 2 no. 1. and Vol. 2 no. 2. Five issues of underground photographer and artist Charles Gatewood’s irregularly published photography paper. Issues feature work by the Lower East Side counterculture crowd Gatewood associated with, including George W. Gardner, Elaine Mayes, Ramon Muxter, Marcia Resnick, Toby Old, tattooist Spider Webb, author Marco Vassi, and more. -

OTHER CAMP: RETHINKING CAMP, the 1990S, and the POLITICS of VISIBILITY

OTHER CAMP: RETHINKING CAMP, THE 1990s, AND THE POLITICS OF VISIBILITY By Sarah Margaret Panuska A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of English—Doctor of Philosophy 2019 ABSTRACT Other Camp: Rethinking Camp, the 1990s, and the Politics of Visibility By Sarah Margaret Panuska Other Camp pairs 1990s experimental media produced by lesbian, bi, and queer women with queer theory to rethink the boundaries of one of cinema’s most beloved and despised genres, camp. I argue that camp is a creative and political practice that helps communities of women reckon with representational voids. This project shows how primarily-lesbian communities, whether black or white, working in the 1990s employed appropriation and practices of curation in their camp projects to represent their identities and communities, where camp is the effect of juxtaposition, incongruity, and the friction between an object’s original and appropriated contexts. Central to Other Camp are the curation-centered approaches to camp in the art of LGBTQ women in the 1990s. I argue that curation— producing art through an assembly of different objects, texts, or artifacts and letting the resonances and tensions between them foster camp effects—is a practice that not only has roots within experimental approaches camp but deep roots in camp scholarship. Relationality is vital to the work that curation does as an artistic practice. I link the relationality in the practice of camp curation to the relation-based approaches of queer theory, Black Studies, and Decolonial theory. My work cultivates the curational roots at the heart of camp and different theoretical approaches to relationality in order to foreground the emergence of curational camp methodologies and approaches to art as they manifest in the work of Sadie Benning, G.B Jones, Kaucyila Brooke and Jane Cottis, Cheryl Dunye, and Vaginal Davis. -

Dissertation

DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation “We’re Punk as Fuck and Fuck like Punks:”* Queer-Feminist Counter-Cultures, Punk Music and the Anti-Social Turn in Queer Theory Verfasserin Mag.a Phil. Maria Katharina Wiedlack angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. Phil.) Wien, Jänner 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 092 343 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Anglistik und Amerikanistik Betreuerin / Betreuer: Univ. Prof.in Dr.in Astrid Fellner Earlier versions and parts of chapters One, Two, Three and Six have been published in the peer-reviewed online journal Transposition: the journal 3 (Musique et théorie queer) (2013), as well as in the anthologies Queering Paradigms III ed. by Liz Morrish and Kathleen O’Mara (2013); and Queering Paradigms II ed. by Mathew Ball and Burkard Scherer (2012); * The title “We’re punk as fuck and fuck like punks” is a line from the song Burn your Rainbow by the Canadian queer-feminist punk band the Skinjobs on their 2003 album with the same name (released by Agitprop Records). Content 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 2. “To Sir With Hate:” A Liminal History of Queer-Feminist Punk Rock ….………………………..…… 21 3. “We’re punk as fuck and fuck like punks:” Punk Rock, Queerness, and the Death Drive ………………………….………….. 69 4. “Challenge the System and Challenge Yourself:” Queer-Feminist Punk Rock’s Intersectional Politics and Anarchism……...……… 119 5. “There’s a Dyke in the Pit:” The Feminist Politics of Queer-Feminist Punk Rock……………..…………….. 157 6. “A Race Riot Did Happen!:” Queer Punks of Color Raising Their Voices ..……………..………… ………….. 207 7. “WE R LA FUCKEN RAZA SO DON’T EVEN FUCKEN DARE:” Anger, and the Politics of Jouissance ……….………………………….…………. -

PDF Portfolio

2 Clunbury Str, London N1 6TT waterside [email protected] contemporary waterside-contemporary.com tel +44 2034170159 Oreet Ashery waterside contemporary Reactivating The Clean and The Unclean, the protagonists of Vladimir Mayakovsky’s revolutionary 1921 play Mystery-Bouffe, Ashery collaboratively produced a collection of ponchos and headgear. These humble forms of dress made from ubiquitous cleaning materials - dish cloths, wipes, dusters – are the uniforms of speculative purists and partisans, exploited labourers and heroes. Adorned with this couture collection, the cast expose themselves to the inevitable risk of becoming objectified fashion icons. Oreet Ashery The Un/Clean (mermaid) 2014 sculpture textile, paper, tape, metal, plaster installation view at waterside contemporary photo: Jack Woodhouse ASH106 waterside contemporary Reactivating The Clean and The Unclean, the protagonists of Vladimir Mayakovsky’s revolutionary 1921 play Mystery-Bouffe, Ashery collaboratively produced a collection of ponchos and headgear. These humble forms of dress made from ubiquitous cleaning materials - dish cloths, wipes, dusters – are the uniforms of speculative purists and partisans, exploited labourers and heroes. Adorned with this couture collection, the cast expose themselves to the inevitable risk of becoming objectified fashion icons. Oreet Ashery The Un/Clean (the world doesn't have to be as you want it to be/ pizza head) 2014 sculpture textile, paper, tape, metal, plaster installation view at waterside contemporary photo: Jack Woodhouse ASH099 waterside contemporary Reactivating The Clean and The Unclean, the protagonists of Vladimir Mayakovsky’s revolutionary 1921 play Mystery-Bouffe, Ashery collaboratively produced a collection of ponchos and headgear. These humble forms of dress made from ubiquitous cleaning materials - dish cloths, wipes, dusters – are the uniforms of speculative purists and partisans, exploited labourers and heroes. -

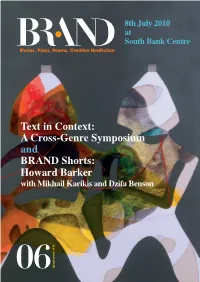

Howard Barker with Mikhail Karikis and Dzifa Benson

8th July 2010 at South Bank Centre Stories, Plays, Poems, Creative NonFiction Text in Context: A Cross-Genre Symposium and BRAND Shorts: Howard Barker with Mikhail Karikis and Dzifa Benson 06 Spring/Summer 2010 Text in Context: A Cross-Genre Symposium July 8th, Function Room, Level 5, Royal Festival Hall, 11am-5pm Programme Events are compered by Cherry Smyth Session 1 11am-12noon Sounding Stories: Anjan Saha, Jay Bernard & William Fontaine Chaired by: Anthony Joseph In the Frame and tablapoetry by Anjan Saha 01 Anjan Saha’s work In the Frame looks at diaspora identities and his tablapoetry brings ancient Indian rhythmic philosophy into present day focus. Poetry & comics by Jay Bernard 02 Jay Bernard will be reading three short poems, about pregnancy, childhood and pre-sexual desire, from two different books: - Your Sign is Cuckoo, Girl (“Kites” & “Eight”) - City State (“A Milken Bud”); accompanied by projections of comic strips. Diary of the Out: spoken word, sound work and 03 music by William Fontaine William Fontaine has crafted Diary of the Out, specially for this symposium, using his knowledge and synthesis of word, music, architecture and the esoteric. It is a short text (which will be expanded as a larger body of work) and soundwork, combining magical realism, non & science fi ction. Session 2 12-1pm Texted Image: Margareta Kern, Uriel Orlow, Oreet Ashery Chaired by: Cherry Smyth On being a guest by Margareta Kern 01 Kern will be discussing her current project ‘Guests’, based on the mass labour migration from the socialist Yugoslavia to West Germany in the late 1960’s. -

A Look at 'Fishy Drag' and Androgynous Fashion: Exploring the Border

This is a repository copy of A look at ‘fishy drag’ and androgynous fashion: Exploring the border spaces beyond gender-normative deviance for the straight, cisgendered woman. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/121041/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Willson, JM orcid.org/0000-0002-1988-1683 and McCartney, N (2017) A look at ‘fishy drag’ and androgynous fashion: Exploring the border spaces beyond gender-normative deviance for the straight, cisgendered woman. Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty, 8 (1). pp. 99-122. ISSN 2040-4417 https://doi.org/10.1386/csfb.8.1.99_1 (c) 2017, Intellect Ltd. This is an author produced version of a paper published in Critical Studies in Fashion and Beauty. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 JACKI WILLSON University of Leeds NICOLA McCARTNEY University of the Arts, London and University of London A look at ‘fishy drag’ and androgynous fashion: Exploring the border spaces beyond gender-normative deviance for the straight, cisgendered woman Abstract This article seeks to re-explore and critique the current trend of androgyny in fashion and popular culture and the potential it may hold for gender deviant dress and politics. -

Империя Jay Z: Как Парень С Улицы Попал В Список Forbes Zack O'malley Greenburg Empire State of Mind: How Jay Z Went from Street Corner to Corner Office

Зак Гринберг Империя Jay Z: Как парень с улицы попал в список Forbes Zack O'Malley Greenburg Empire State of Mind: How Jay Z Went from Street Corner to Corner Office Copyright © 2011, 2012, 2015 by Zack O’Malley Greenburg All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. This edition published by arrangement with Portfolio, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC © Гусева А., перевод, 2017 © Оформление. ООО «Издательство «Эксмо», 2017 * * * Введение Четвертого октября 1969 года в 00 часов 10 минут по верхнему уровню Мертл- авеню в последний раз прогрохотал поезд наземки, навсегда скрывшись в ночи[1]. Два месяца спустя Шон Кори Картер, более известный как Jay Z, появился на свет и обрел свой первый дом в расположенном поблизости Марси Хаузес. Сейчас этот раскинувшийся на значительной территории комплекс однообразных шестиэтажных кирпичных зданий отделен пятью жилыми блоками от призрачных руин линии Мертл- авеню, вытянутой полой конструкции, которую никто так и не потрудился снести. В годы формирования личности Jay Z остальная территория Бедфорд-Стайвесант подобным же образом игнорировалась властями. В 1980-е, с расцветом наркоторговли, уроки спроса и предложения можно было получить за каждым углом. Прошлое Марси до сих пор дает о себе знать: железные ворота с внушительными замками, охраняющие парковочные места; номера квартир, белой краской выписанные по трафарету под каждым окном, выходящим на улицу, призванные помочь полиции в поисках скрывающихся преступников; и, конечно, скелет железной дороги над Мертл-авеню, буквально в нескольких шагах от современной станции, на которой теперь останавливаются поезда маршрутов J и Z. На этих страницах вы найдете подробную историю пути Jay Z от безрадостных улиц Бруклина к высотам мира бизнеса. -

Oreet Ashery's Party for Freedom

Oreet Ashery Party for Freedom 07.09. - 27.10.2013 Oreet Ashery: Party for Freedom | An Audiovisual Album: Geert Wilders Triptych, 2013, video still The Unfinished Revolution: Oreet Ashery’s Party for Freedom By TJ Demos In ”Geert Wilders Triptych”, track 8 of Oreet extreme-right Partij voor de Vrijheid (Party Ashery’s hour-long video Party for Freedom for Freedom). As such, her moving-image | An Audiovisual Album (2013), a man is work, constituting ten interconnected tracks, shown chasing a woman around the grass, reveals what Fredric Jameson would call the grunting “Geert” as they go. Both are naked “political unconscious” of rightwing political and on all fours. Tracking his female prey in discourse, exposing its underlying “proble- this bizarre tale of sexual experimentation matics of ideology, of the unconscious and and political theatre – “Geert” references of desire, of representation, of history, and Dutch rightwing politician Geert Wilders – of cultural production.”1 the man kicks like a donkey, and eventually succeeds in grabbing her leg and bringing Coming after two years of research, As- her down face-first on the ground, as a dog hery’s video interweaves complex elements looks on and appears miffed by the curio- of experimental performance, nude theatre us display. Reminiscent of the scene of the and political satire, punk music and trash nude chase in The Idiots, Lars von Trier’s aesthetics, in order to deconstruct, via cut- 1998 comedy-drama film in which characters ting parody, the paradoxical ideology that attempt to get in touch with their inner-idiot joins the freedoms of sexual transgression to in a related critical acting-out of European the xenophobic and murderous intolerance libertarianism-become-libertinage, Ashery’s of outsiders. -

A Study in Scarlet 17

Press kit A Study in Scarlet 17. 05–22. 07.2018 Press visit, Wednesday 16th May, at 9.30am Grand opening, Wednesday 16th May, from 6pm to 9pm With Ethan Assouline, Beau Geste Press, Lynda Benglis, Kévin Blinderman : masternantes, Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz, Jean-Louis Brau & Claude Palmer, Monte Cazazza, Chris & Cosey, COUM Transmissions, Vaginal Davis, Brice Dellsperger, Casey Jane Ellison, Harun Farocki, Karen Finley, Brion Gysin, Hendrik Hegray, Her Noise Archive, Robert Morris, Ebecho Muslimova, Meret Oppenheim, Pedro, Muriel & Esther, Lili Reynaud-Dewar, Christophe de Rohan Chabot, Louise Sartor, Throbbing Gristle, Cosey Fanni Tutti, Amalia Ulman and Les Vagues. Exhibition curator : Gallien Déjean Action Jusqu’à la Balle Crystal, 9e Biennale de Paris, 1975 © Courtesy Cosey Fanni Tutti et Cabinet, Londres Contacts : Isabelle Fabre, Communication Manager > +33 1 76 21 13 26 > [email protected] Lorraine Hussenot, Press Officer > +33 1 48 78 92 20 > [email protected] +33 6 74 53 74 17 Le frac île-de-France- reçoit le soutien du le plateau, paris Conseil régional d’Île-de-France, du ministère 22, rue des Alouettes de la Culture – Direction Régionale des Affaires 75 019 Paris, France Culturelles d’Île-de-France et de la Mairie de Paris. T +33 (0)1 76 21 13 20 Membre du réseau Tram, de Platform, fraciledefrance.com regroupement des FRAC et du Grand Belleville 1 Press kit Contents 1. Press release —A Study in Scarlet /p. 3-4 2. Cosey Fanni Tutti, Art Sex Music —Extracts /p. 5 3. Notices /p. 6-16 4. Images available /p. 17-19 5. -

MA-2013 07 the New Yorker

Allen, Emma. “The Rapper is Present,” The New Yorker, July 11, 2013 JULY 11, 2013 THE RAPPER IS PRESENT POSTED BY EMMA ALLEN Three years ago, when the performance artist Marina Abramović sat in the atrium of the Museum of Modern Art for seven hundred and fifty hours, many of the people who had waited in long lines to sit across from her melted down in her presence. Abramović remained silent and still, enduring thirst, hunger, and back pain (and speculation as to how, exactly, she was or was not peeing), while visitors, confronted with her placid gaze, variously wept, vomited, stripped naked, and proposed marriage. But the other day, at the Pace Gallery in Chelsea, where Jay-Z was presenting his own take on Abramović’s piece—rapping for six hours in front of a rotating cast of art-world V.I.P.s—viewers’ primary response was to get up and dance. Jay-Z (or Shawn Carter, or Hova, as he’s alternately known) was continuously performing “Picasso Baby,” the second song on his new album, “Magna Carta… Holy Grail,” to a succession of visual artists, museum directors, gallerists, Hollywood folk, and Pablo’s granddaughter Diana Widmaier Picasso. These guests took turns on or near a wooden bench positioned across from a low platform on which the rapper stood, except when he was prowling around. A crowd of less famous art-world denizens and cool-looking people (some of whom had been specially cast) loitered along the walls of the gallery, except when they were invited to scurry right up to Jay-Z.