Or. Choor Singh Sidhu Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guru Tegh Bahadur

Second Edition: Revised and updated with Gurbani of Guru Tegh Bahadur. GURU TEGH BAHADUR (1621-1675) The True Story Gurmukh Singh OBE (UK) Published by: Author’s note: This Digital Edition is available to Gurdwaras and Sikh organisations for publication with own cover design and introductory messages. Contact author for permission: Gurmukh Singh OBE E-mail: [email protected] Second edition © 2021 Gurmukh Singh © 2021 Gurmukh Singh All rights reserved by the author. Except for quotations with acknowledgement, no part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or medium without the specific written permission of the author or his legal representatives. The account which follows is that of Guru Tegh Bahadur, Nanak IX. His martyrdom was a momentous and unique event. Never in the annals of human history had the leader of one religion given his life for the religious freedom of others. Tegh Bahadur’s deed [martyrdom] was unique (Guru Gobind Singh, Bachittar Natak.) A martyrdom to stabilize the world (Bhai Gurdas Singh (II) Vaar 41 Pauri 23) ***** First edition: April 2017 Second edition: May 2021 Revised and updated with interpretation of the main themes of Guru Tegh Bahadur’s Gurbani. References to other religions in this book: Sikhi (Sikhism) respects all religious paths to the One Creator Being of all. Guru Nanak used the same lens of Truthful Conduct and egalitarian human values to judge all religions as practised while showing the right way to all in a spirit of Sarbatt da Bhala (wellbeing of all). His teachings were accepted by most good followers of the main religions of his time who understood the essence of religion, while others opposed. -

Development of Sikh Institutions from Guru Nanak Dev to Guru Gobind Singh

© 2018 JETIR July 2018, Volume 5, Issue 7 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Development of Sikh Institutions From Guru Nanak Dev to Guru Gobind Singh Dr. Sukhjeet Kaur Bhullar Talwandi Sabo assistant professor Guru Kashi University Talwandi Sabo Baldev Singh M.Phill Research Scholar Guru Nanak Dev established new institutions of Sangat and Pangat. Men and women of any caste could join the Sangat. The Sangat used to gather to listen to the teachings of Guru Nanak Dev. The Pangat meant taking food in a queue. Everybody was entitled to partake Langar without any discrimination of caste or satatus (high or low). Those two institutions proved revolutionary for the Hindu society. Langar system was introduced by Guru Nanak Dev and Guru Angad Dev expanded it. Guru Angad Dev organized the institution of Sangat more effectively founded by Guru Nanak Dev. The ‘Sangat’ means ‘sitting together collectively’. There was no restriction of any kind in joining the Sangat. All people could take part in it. The Sangat was considered to be a replica of God. The Sangat met every morning and evening to listen to the Bani of Guru Angad Dev. That institution not only brought the Sikhs under one banner but it also helped a lot in the success of Sikh missionary work. Thus, the contribution of the institution of Sangat to the development of Sikhism was extremely great. Guru Nanak Dev started the institution of Langar. Guru Amar Das Ji expanded it greatly. Guru Amar Das declared that no visitor could meet him unless he had taken the Langar. -

Life Stories of the Sikh Saints

LIFE STORIES OF THE SIKH SAINTS HARBANS SINGH DOABIA Singh Brothers Antrlt•ar brr All rights of all kinds, including the rights of translation are reserved by Mrs . Harbans Singh Doabia ISBN 81-7205-143-3 First Edition February 1995 Second Edition 1998 Third Edition January 2004 Price : Rs. 80-00 Publishers : Singh Brothers • Bazar Mai Sewan, Amritsar -143 006 • S.C.O. 223-24, City Centre, Amritsar - 143 001 E-mail : [email protected] Website: www.singhbrothers.com Printers: PRINTWELL, 146, INDUSTRIAL FOCAL POINT, AMRITSAR. CONTENTS 1. LIFE STORY OF BABA NANO SINGH JI 1. Birth and Early Years 9 2. Meetings with Baba Harnam Singh Ji 10 3. Realisation 11 4. Baba Harnam Singh Ji of Bhucho 12 5. The Nanaksar Thaath (Gurdwara) 15 6. Supernatural Powers Served Baba Nand Singh Ji 17 7. Maya (Mammon) 18 8. God sends Food, Parshad and all necessary Commodities 19 9. Amrit Parchar-Khande Da Amrit 20 10. Sukhmani Sahib 21 11. Utmost Respect should be shown to Sri Guru Granth Sahib 21 12. Guru's Langar 22 13. Mandates of Gurbani 23 14. Sit in the Lap of Guru Nanak Dev Ji 26 15. Society of the True Saints and the True Sikhs 26 16. The Naam 27 17. The Portrait of Guru Nanak Dev Ji 28 18. Rosary 29 19. Pooranmashi and Gurpurabs 30 20. Offering Parshad (Sacred Food) to the Guru 32 21. Hukam Naamaa 34 22. Village Jhoraran 35 23. At Delhi 40 24. Other Places Visited by Baba Ji 41 25. Baba Ji's Spiritualism and Personality 43 26. -

Guru Nanak and His Bani

The Sikh Bulletin cyq-vYswK 547 nwnkSwhI March-April 2015 ੴ ਸਤਿ ਨਾਮੁ ਕਰਿਾ ਪੁਰਖੁ ਤਨਰਭਉ ਤਨਰਵੈਰੁ ਅਕਾਲ ਮੂਰਤਿ ਅਜੂਨੀ ਸੈਭੰ ਗੁਰ ਪਰਸਾਤਿ ॥ Ik oaʼnkār saṯ nām karṯā purakẖ nirbẖa▫o nirvair akāl mūraṯ ajūnī saibẖaʼn gur parsāḏ. THE SIKH BULLETIN GURU NANAK AND HIS BANI cyq-vYswK 547 nwnkSwhI jyT-hwV 547 nwnkSwhI [email protected] Volume 17 Number 3&4 Published by: Hardev Singh Shergill, President, Khalsa Tricentennial Foundation of N.A. Inc; 3524 Rocky Ridge Way, El Dorado Hills, CA 95762, USA Fax (916) 933-5808 Khalsa Tricentennial Foundation of N.A. Inc. is a religious tax-exempt California Corporation. In This Issue/qqkrw I HAVE NO RELIGION My Journey of Finding Guru Nanak (1469-1539) I have no Religion…………………………….……1 The One and Only A Labour of Respect: Working with Peace on Earth will not prevail until all the manmade Religions and Devinder Singh Chahal Ph D………………….…..2 Gurbani, Logic and Science, their Gods are DEAD and mankind learns to live within Hukam. Prof. Devinder Singh Chahal………………………5 First time I said that was at age twelve. Fifty years later, when a Finding Guru Nanak (1469-1539) responsibility to operate a Gurdwara was thrust upon me, I tried my best to Hardev Singh Shergill…………………………….14 become a Gursikh; but eighteen years into that effort made me realize that Editorials on Guru Nanak a Gursikh has no place in Sikhism. That was a great disappointment but Hardev Singh Shergill………………………36 not for long because I soon discovered that I was in excellent company of Sikh Awareness Seminar, no other than Guru Nanak himself, the One and Only gift of the Creator to April 11, 2015, Calgary, Canada…………...71 mankind, and under whose name Sikhism as a religion is being touted. -

4 Comparative Law and Constitutional Interpretation in Singapore: Insights from Constitutional Theory 114 ARUN K THIRUVENGADAM

Evolution of a Revolution Between 1965 and 2005, changes to Singapore’s Constitution were so tremendous as to amount to a revolution. These developments are comprehensively discussed and critically examined for the first time in this edited volume. With its momentous secession from the Federation of Malaysia in 1965, Singapore had the perfect opportunity to craft a popularly-endorsed constitution. Instead, it retained the 1958 State Constitution and augmented it with provisions from the Malaysian Federal Constitution. The decision in favour of stability and gradual change belied the revolutionary changes to Singapore’s Constitution over the next 40 years, transforming its erstwhile Westminster-style constitution into something quite unique. The Government’s overriding concern with ensuring stability, public order, Asian values and communitarian politics, are not without their setbacks or critics. This collection strives to enrich our understanding of the historical antecedents of the current Constitution and offers a timely retrospective assessment of how history, politics and economics have shaped the Constitution. It is the first collaborative effort by a group of Singapore constitutional law scholars and will be of interest to students and academics from a range of disciplines, including comparative constitutional law, political science, government and Asian studies. Dr Li-ann Thio is Professor of Law at the National University of Singapore where she teaches public international law, constitutional law and human rights law. She is a Nominated Member of Parliament (11th Session). Dr Kevin YL Tan is Director of Equilibrium Consulting Pte Ltd and Adjunct Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore where he teaches public law and media law. -

Toba Tek Singh Short Stories (Ii) the Dog of Tithwal

Black Ice Software LLC Demo version WELCOME MESSAGE Welcome to PG English Semester IV! The basic objective of this course, that is, 415 is to familiarize the learners with literary achievements of some of the significant Indian Writers whose works are available in English Translation. The course acquaints you with modern movements in Indian thought to appreciate the treatment of different themes and styles in the genres of short story, fiction, poetry and drama as reflected in the prescribed translations. You are advised to consult the books in the library for preparation of Internal Assessment Assignments and preparation for semester end examination. Wish you good luck and success! Prof. Anupama Vohra PG English Coordinator 1 Black Ice Software LLC Demo version 2 Black Ice Software LLC Demo version SYLLABUS M.A. ENGLISH Course Code : ENG 415 Duration of Examination : 3 Hrs Title : Indian Writing in English Total Marks : 100 Translation Theory Examination : 80 Interal Assessment : 20 Objective : The basic objective of this course is to familiarize the students with literary achievement of some of the significant Indian Writers whose works are available in English Translation. The course acquaints the students with modern movements in Indian thought to compare the treatment of different themes and styles in the genres of short story, fiction, poetry and drama as reflected in the prescribed translations. UNIT - I Premchand Nirmala UNIT - II Saadat Hasan Manto, (i) Toba Tek Singh Short Stories (ii) The Dog of Tithwal (iii) The Price of Freedom UNIT III Amrita Pritam The Revenue Stamp: An Autobiography 3 Black Ice Software LLC Demo version UNIT IV Mohan Rakesh Half way House UNIT V Gulzar (i) Amaltas (ii) Distance (iii)Have You Seen The Soul (iv)Seasons (v) The Heart Seeks Mode of Examination The Paper will be divided into section A, B and C. -

NIE News September 2013.Pdf

An Institute of Distinction September 2013 No.85 ISSN 0218-4427 GROWING EXCELLENCE 3 CORPORATE DEVELOPMENT Latest campus news 14 SPECIAL FEATURE Teachers’ Investiture Ceremony July 2013 RESEARCH 20 Highlights on experts and projects A member of An Institute of INTERNATIONAL ALLIANCE of LEADING EDUCATION INSTITUTES Editorial Team: Associate Professor Jason Tan Eng Thye, Patricia Campbell, Monica Khoo, Julian Low NIE News is published quarterly by the Public International and Alumni Relations CONTENTS Department, National Institute of Education, CORPORATE DEVELOPMENT Staff Welfare Recreation Fund Singapore. Malay Values and Graces Camp 3 Committee Activities 19 Design by Graphic Masters & Advertising Asian Regional Association for Pte Ltd Home Economics Congress 2013 4 SPECIAL FEATURE NIE News is also available at: www.nie.edu.sg/nienews Learning Week for Staff 4 Teachers’ Investiture Ceremony July 2013 14 - 15 If you prefer to receive online versions English Language and Literature of NIE News, and/or wish to update your particulars please inform: Postgraduate Conference 2013 5 RESEARCH Arts Education Talk 5 The Editorial Team, NIE News C J Koh Professorial Lecture – 1 Nanyang Walk, Singapore 637616 NIE Art Collection Launch 6 Professor Linda Darling-Hammond 20 Tel: +65 6790 3034 Visual and Performing Arts Farewell Professor Fax: +65 6896 8874 Academic Group hosts A. Lin Goodwin 21 Email: [email protected] Hong Kong Institute of LSL academics and staff clinch Education visitors 7 more awards 22 Prominent Visitors 8 - 9 9th Asia-Pacific -

Dasvandh Network

Dasvandh To selflessly give time, resources, and money to support Panthic projects www.dvnetwork.org /dvnetwork @dvnetwork Building a Nation The Role of Dasvandh in the Formation of a Sikh culture and space Above: A painting depicting Darbar Sahib under construction, overlooked by Guru Arjan Sahib. www.dvnetwork.org /dvnetwork @dvnetwork Guru Nanak Sahib Ji Guru Nanak Sahib’s first lesson was an act of Dasvandh: when he taught us the true bargain: Sacha Sauda www.dvnetwork.org /dvnetwork @dvnetwork 3 Golden Rules The basis for Dasvandh are Guru Nanak Sahib’s key principles, which he put into practice in his own life Above: Guru Nanak Sahib working in his fields Left: Guru Nanak Sahib doing Langar seva www.dvnetwork.org /dvnetwork @dvnetwork Mata Khivi & Guru Angad Sahib Guru Angad Sahib ji and his wife, the greatly respected Mata Khivi, formalized the langar institution. In order to support this growing Panthic initiative, support from the Sangat was required. www.dvnetwork.org /dvnetwork @dvnetwork Community Building Guru Amar Das Sahib started construction on the Baoli Sahib at Goindval Sahib.This massive construction project brought together the Sikhs from across South Asia and was the first of many institution- building projects in the community. www.dvnetwork.org /dvnetwork @dvnetwork Guru RamDas Sahib Ji Besides creating the sarovar at Amritsar, Guru RamDas Sahib Ji designed and built the entire city of Amritsar www.dvnetwork.org /dvnetwork @dvnetwork Guru Arjan Sahib & Dasvandh It was the monumental task of building of Harmandir Sahib that allowed for the creation of the Dasvandh system by Guru Arjan Sahib ji. -

Kirpal-Singh-The-Jap-Ji.Pdf

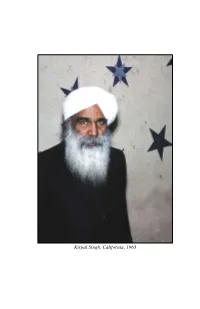

INTRODUCTION Kirpal Singh, California, 1963 THE JAP JI INTRODUCTION THE JAP JI By Krpal Sngh “Man’s only duty is to be ever grateful to God for His innumerable gifts and blessings.” THE JAP JI about the translator . Krpal Sngh, a modern Sant n the drect lne of Guru Nanak, was born n 1894 n the Punjab n Inda (now part of Pakstan). Hs long lfe, saturated wth love for God and humanity, brought peace and fulfillment to approximately 120,000 dscples, scattered all over the world. He taught the natural way to find God while living; and His life was the embodment of Hs teachngs. He made three world tours, was Presdent of the World Fellowshp of Relgons for four- teen years, and convened the World Conference on Unty of Man n February 1974, attended by relgous, socal and poltcal leaders from all over the world. He ded on August 21, 1974, in his eighty-first year, stepping out of his body in full consciousness; His last words were of love for His dis- cples. Hs lfe bears eloquent testmony that the age of the prophets is not over; that it is still possible for human beings to find God and reflect His will. v v INTRODUCTION THE JAP JI The Message of Guru Nanak Literal Translation from the Original Punjabi Text with Introduction, Commentary, Notes, and a Biographical Study of Guru Nanak By Krpal Sngh A RUHANI SATSANG® BOOK RUHANI SATSANG DIVINE SCIENCE OF THE SOUL v v THE JAP JI I have written books without any copyright—no rights reserved — because it is a Gift of God, given by God, as much as sunlight; other gifts of God are also free. -

Health Care Providers' Handbook on Hindu Patients

Queensland Health Health care providers’ handbook on Hindu patients © State of Queensland (Queensland Health) 2011. This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution, Non-Commercial, Share Alike 2.5 Australia licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/au/deed.en You are free to copy, communicate and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute Queensland Health and distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license. For permissions beyond the scope of this licence contact: Intellectual Property Officer Queensland Health GPO Box 48 Brisbane Queensland 4001 Email: [email protected] Phone +61 7 3234 1479 For further information contact: Queensland Health Multicultural Services Division of the Chief Health Officer Queensland Health PO Box 2368 Fortitude Valley BC Queensland 4006 Email: [email protected] Suggested citation: Queensland Health. Health Care Providers’ Handbook on Hindu Patients. Division of the Chief Health Officer, Queensland Health. Brisbane 2011. Photography: Nadine Shaw of Nadine Shaw Photography Health care providers’ handbook on Hindu patients Table of contents Preface .................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................ 5 Section one: Guidelines for health services . 6 1 Communication issues .................................... 7 2 Interpreter services ....................................... 7 3 Patient rights ........................................... -

![UZR W]Zvd $*# ^`Cv E` Wcvvu`^](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8533/uzr-w-zvd-cv-e-wcvvu-848533.webp)

UZR W]Zvd $*# ^`Cv E` Wcvvu`^

* + 7!4 8 5 ( 5 5 VRGR '%&((!1#VCEB R BP A"'!#$#1!$"$#$%T utqBVQWBuxy( (*+,(-'./ ,2,23 0,-1$( ,-./ 31<O62!12!&/$.& @ /< '% 261&$/$ 42/1$/%-; <3 .1<&/.1%.& 23&6 %2 /$!-< 26-$&/ 6& -1$6&$%6 -1& 4$&61 31&!$!12$6-624<@ &$6/$ 2!<12/$ 2>&-%&!$< $2</4.=?- 4216&4% 1=426&.&4>$'&=3&4& / - !$%&' (() *99 :& (2 & 0 1&0121'3'1& " # $ 2342/1$ 2342/1$ s the new I-T portal con- tepping up efforts to bring its Atinued to have glitches and Scitizens back home, India on remained unavailable for two Sunday airlifted 392 people, consecutive days, the Finance besides some Afghan politi- Ministry “summoned” Infosys cians, from Kabul to New Delhi. 2342/1$ MD and CEO Salil Parekh on They were evacuated in three Monday to explain to Finance different flights of the Indian mid the Afghanistan crisis Minister Nirmala Sitharaman Air Force (IAF) and Air India. Aand India’s ongoing evac- the reasons for the continued Some more flights are planned uation exercise following the snags even after over two in the days to come to safely Taliban takeover of the coun- months of the site’s launch. bring back stranded Indian cit- try, Union Housing and Urban However, just ahead of the izens from Afghanistan. Affairs Minister Hardeep Singh meeting with Sitharaman, A team of Indian officials Puri on Sunday cited the evac- Infosys late on Sunday night is now based in Kabul to assist uations from Afghanistan to said that emergency mainte- those Indians who want to back the controversial nance on the website had been return home. -

The Five Dacoits the Five Perversions of Mind from the Path of the Masters by Julian Johnson Sant Kirpal Singh Ji, Hazur Baba Sawan Singh Ji, and Others

The Five Dacoits The Five Perversions of Mind From The Path of the Masters by Julian Johnson Sant Kirpal Singh Ji, Hazur Baba Sawan Singh Ji, and others We are constantly beset by five foes - passion, anger, greed, worldly attachments, and vanity. All these must be mastered, brought under control. You can never do that entirely until you have the aid of the Guru and are in harmonic relations with the Sound Current. But you can begin now, and every effort will be a step on the way. (Baba Sawan Singh, Spiritual Gems, 339) Swami Ji has said that we should not hesitate to go all out to still the mind. We do not fully grasp that the mind takes everyone to his doom. It is like a thousand-faced snake, which is constantly with each being; it has a thousand different ways of destroying the person. The rich with riches, the poor with poverty, the orator with his fine speeches – it takes the weakness in each and plays upon it to destroy him. (Sant Kirpal Singh Ji) ruhanisatsangusa.org/serpent.htm Contents Page: 1. The Five Perversions of Mind, from The Path of the Masters, by Julian Johnson 2. Biography of Julian Johnson, from Wikipedia 3. Lust– Julian Johnson 5. The Case for Chastity, Parts 1 & 2 from Sat Sandesh 6. Sant Kirpal Singh Ji on Chastity 7. Hazur Baba Sawan Singh 8. Anger– Julian Johnson 10. Anger Quotes 11. Sant Kirpal Singh on Anger 12. Baba Sawan Singh, Jack Kornfield 13. Greed– Julian Johnson 14. Greed Quotes 15.