Working Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

00 Stage 1 Final Report

Action Plan for Heritage Conservation and Environment Improvement of Erangal Precinct INCEPTION REPORT May 2010 Submitted to Mumbai Metropolitan Region – Heritage Conservation Society (MMR-HCS) MMRDA, Bandra Kurla Complex, Bandra (East), Mumbai 400 051 Prepared by HCP Design and Project Management Pvt. Ltd. Paritosh, Usmanpura, Ahmedabad- 380 013 Action Plan for Erangal Precinct PROJECT TEAM Project Director Shirley Ballaney, Architect – Urban and Regional Planner Project Leader Bindu Nair, Geographer – Urban and Regional Planner The Team Sonal Shah, Architect – Urban Planner Archana Kothari, Architect – Urban Planner Krupa Bhardwaj, Architect – Urban Planner Rashmita Jadav, Architect Atul Patel, CAD Specialist Suresh Patel, CAD Technician Action Plan for Erangal Precinct CONTENTS 1 Background to the Project 1.1 Significance of the Project 1.2 Objectives of the Project 1.3 Scope of Work (TOR) 1.4 Outputs and Schedule 2 Detailed SOW and Road Map 2.1 Detailed SOW and Methodology 2.2 Work Plan 2.3 Changed Focus of the Project 3 Base Map 4 Introduction 4.1 Location and Connectivity 4.2 Regional Context 4.3 History and Growth of Erangal 5 Preliminary Assessments 5.1 Development Plan Proposals 5.2 Built Fabric and Settlement Structure/Pattern 5.3 Access and Road Networks 5.4 Land Use 5.5 Intensity of development/FSI utilization 5.6 Land Ownership Pattern 5.7 Landmarks and public spaces 5.8 Community Pattern 5.9 Occupational Pattern 5.10 Typology of Structures 5.11 Cultural Practices 5.12 Sewerage 5.13 Solid Waste Management 5.14 Social Amenities 6 Review of the Precinct Boundary 6.1 Rational for Revising the Precinct Boundary 6.2 Details of the Revised Precinct Boundary and the Buffer Zone Appendices Appendix 1: Review of some of the Material Appendix 2: Questionnaire Action Plan for Erangal Precinct LIST OF MAPS Map No. -

Draft Report on the Study of Lakes on Mumbai

Draft report on the Study of Lakes on Mumbai. 22nd March, 2009 Project team Dr. Goldin Quadros Ms. Gauri Gurav Field Team Mr. Vishal Rasal Mr. Dilip Shenai Mr. Kaustubh Bhagat. World Wide Fund for Nature – India, Maharashtra State Office 204 National Insurance Building, Dr. D.N. Road, Fort Mumbai 400 001. Introduction It is well known that Mumbai city is comprised of seven islands till 1857. Gradually with invasion the islands were merged by the invaders and now the entire city is one big island. The island city has a rich heritage of natural resources like the forests, lakes mangroves, etc. The city in the past was self sufficient in terms of the basic amenities like housing, food, water, electricity it provided to its inhabitants. However with growing population and pollution the city is now adding to the pressure on the adjacent districts for its water and electricity requirements. It is common knowledge that Mumbai has three lakes i.e. Tulsi, Powai and Vihar that used to provide water to Mumbai residents. Very few actually know that the city is blessed with many more in its BMC jurisdiction. These lakes are either polluted by human sewage or industrial effluents and have remained neglected with increasing urbanization. With depleting forests and water resources it is about time that the existing lakes are given a chance to serve the society again. How do we define lakes? There is considerable uncertainty about defining the difference between lakes and ponds. For example, limnologists have defined lakes as waterbodies which are simply a larger version of a pond or which have wave action on the shoreline, or where wind induced turbulence plays a major role in mixing the water column. -

Study of Housing Typologies in Mumbai

HOUSING TYPOLOGIES IN MUMBAI CRIT May 2007 HOUSING TYPOLOGIES IN MUMBAI CRIT May 2007 1 Research Team Prasad Shetty Rupali Gupte Ritesh Patil Aparna Parikh Neha Sabnis Benita Menezes CRIT would like to thank the Urban Age Programme, London School of Economics for providing financial support for this project. CRIT would also like to thank Yogita Lokhande, Chitra Venkatramani and Ubaid Ansari for their contributions in this project. Front Cover: Street in Fanaswadi, Inner City Area of Mumbai 2 Study of House Types in Mumbai As any other urban area with a dense history, Mumbai has several kinds of house types developed over various stages of its history. However, unlike in the case of many other cities all over the world, each one of its residences is invariably occupied by the city dwellers of this metropolis. Nothing is wasted or abandoned as old, unfitting, or dilapidated in this colossal economy. The housing condition of today’s Mumbai can be discussed through its various kinds of housing types, which form a bulk of the city’s lived spaces This study is intended towards making a compilation of house types in (and wherever relevant; around) Mumbai. House Type here means a generic representative form that helps in conceptualising all the houses that such a form represents. It is not a specific design executed by any important architect, which would be a-typical or unique. It is a form that is generated in a specific cultural epoch/condition. This generic ‘type’ can further have several variations and could be interestingly designed /interpreted / transformed by architects. -

Section 4 Manuals As Per Provision of RTI Act 2005 of P/NORTH Ward

BRIHANMUMBAI MAHANAGARPALIKA Section 4 Manuals as per provision of RTI Act 2005 of P/NORTH Ward ASSTT. ENGINEER (MAINT.) DEPARTMENT Address - Office of Asstt. Engineer (Maint), Gr.Floor, P/North Ward Building, Liberty Garden, Mamletdarwadi Road, Malad (West), Mumbai- 400064 INDEX Section 4 (1) B © Description of the Chapter’s Contents Page No. Sub Clauses Introduction 3-4 1 4 (1) (b) (i) Particulars of Organization, Function and Duties 5-19 2 4 (1) (b) (ii) Powers and Duties of Officers and Employees 20-45 Procedure followed in Decision Making Process 3 4 (1) (b) (iii) 46-54 including Channels of supervision and accountability 4 4 (1) (b) (iv) Norms set for discharge of its functions 55 The rules, regulation, instruction, manuals and 5 4 (1) (b) (v) records, held by it or under its control or used by the 56 employees for discharging department functions Statement of categories of documents that are held 6 4 (1) (b) (vi) and under the control of the office of Asstt. Engineer 57-58 (M & R) Particulars of any arrangement that exists for consultation with the members of the public in 7 4 (1) (b) (vii) 59 relation to the formulation of the department’s policy and implementation thereof. A Statement of the boards, councils, committees and other bodies consisting of two or more persons constituted as its part or far the purpose of its advice, 8 4 (1) (b) (viii) and as to whether meetings of those boards, 60 councils, committees and other bodies are open to the public or the minutes of such meetings are accessible for public. -

ANSWERED ON:27.07.2017 Inland Waterways Kirtikar Shri Gajanan Chandrakant;S.R

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA SHIPPING LOK SABHA STARRED QUESTION NO:161 ANSWERED ON:27.07.2017 Inland Waterways Kirtikar Shri Gajanan Chandrakant;S.R. Shri Vijay Kumar Will the Minister of SHIPPING be pleased to state: (a) the details and the present implementation status of the Inland Vessels (Prevention and Control of Pollution and Protection of Inland Water) Rules, 2016 in the country; (b) the details of the projects under execution for expeditious transportation of cargo and passengers and development of tourism through inland waterways across the country; (c) whether the Government has worked out a plan to encourage the use of waterways for being more economical, customer friendly and smooth movement of goods and passengers and if so, the details thereof; (d) the steps proposed to be taken by the Government to boost shipping tourism in the country particularly from Mumbai to Elephanta Cave, Kolkata to Ganga Sagar and Dwarka Section; and (e) the steps taken/proposed to be taken by the Government for modernization of major Ports for easy and smooth movement of goods? Answer MINISTER OF SHIPPING (SHRI NITIN GADKARI) (a)to(e): A Statement is laid on the table of the House. Statement referred to in reply to parts (a) to (e) of LokSabha Starred Question no.161 for 27.07.2017 raised by Shri S. R. Vijayakumar& Shri GajananKirtikar, M.Ps on "Inland Waterways" (a): Under the Inland Vessels Act, 1917, the Inland Vessels (Prevention and Control of Pollution of Inland Water) Rules, 2016 were notified in July, 2016 and laid on the table of both the houses of Parliament. -

Mumbai North District – Maharashtra

Mumbai North District – Maharashtra Sl. Name of the Complete postal E-mail No. Sub-Division address of ACP/Dy. Telephone Numbers along with STD and Police SP/SDPO office and Code Station Police Station along with PIN Code Office Residence Fax 1. Assistant Teen Dongari Police --- --- 28724376 --- Commissioner Quarters, E Bldg., of Police, Ground Floor, Goregaon Goregaon (West), Division Mumbai-400062, Maharashtra 2. Assistant Marve Road, Opp. --- --- 28820497 --- Commissioner Green Village, of Police, Division-Malvani Malvani Church, Malad Division (West), Mumbai- 400095, Maharashtra 3. Assistant Opp. Borivali --- --- 28901639 --- Commissioner Station, Borivali of Police, Polie Station Borivali Compound, 1st floor, Division S.V.Road, Borivali (West), Mumbai- 400092, Maharashtra 4. Assistant Vrindavan Bldg., --- --- 28752181 --- Commissioner Room No.210, 202 of Police, 2nd floor, S.V.Road, Dindoshi Western Express Division Highway, Dindoshi Malad (East), Mumbai-400097, Maharashtra 5. Assistant Samata Nagar Police --- --- 28877624 --- Commissioner Station Compound, of Police, Western Express Samata Nagar Highway, Kandivali Division (East), Mumbai- 400101, Maharashtra 6. Assistant Near Rajashri --- --- 28281069 --- Commissioner Theatre, Dahisar of Police, Police Station Dahisar Division Compound, 1st Floor, S.V. Road, Dahisar (East), Mumbai- 400068, Maharashtra 7. Aarey Police Near Chota Kashmir, --- --- 26858485 --- Station Dinkar Desai Marg, Goregaon (East), Mumbai-400065, Maharashtra 8. Goregaon Police Near Cinemax --- --- 28722495 --- Station Theatre, S.V.Road, Goregaon (West), Mumbai-400062, Maharashtra 9. Malad Police Near Somvar Bazar, --- --- 28821482 --- Station Underai Road, Malad (West), Mumbai- 400064, Maharashtra 10. Kandivali Police Near Kandivali --- --- 28056603 --- Station Telephone Exchange, S.V. Road, Kandivali (West), Mumbai- 400067, Maharashtra 11. Borivali Police Opp. Borivali --- --- 28092331 --- Station Railway Station, S.V. Road, Borivali (West), Mumbai- 400092, Maharashtra 12. -

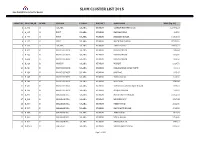

List of Slum Cluster 2015

SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. M.) 1 A_001 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GANESH MURTHI NAGAR 120771.23 2 A_005 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI BANGALIPURA 318.50 3 A_006 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI NARIMAN NAGAR 14315.98 4 A_007 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI MACHIMAR NAGAR 37181.09 5 A_009 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GEETA NAGAR 26501.21 6 B_021 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 939.53 7 B_022 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 1292.90 8 B_023 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 318.67 9 B_029 B MANDVI COLABA MUMBAI MANDVI 1324.71 10 B_034 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI NALABANDAR JOPAD PATTI 600.14 11 B_039 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI JHOPDAS 908.47 12 B_045 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI INDRA NAGAR 1026.09 13 B_046 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MAZGAON 1541.46 14 B_047 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI SUBHASHCHANDRA BOSE NAGAR 848.16 15 B_049 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MASJID BANDAR 277.27 16 D_001 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI MATA PARVATI NAGAR 21352.02 17 D_003 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI BRANHDHARY 1597.88 18 D_006 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI PREM NAGAR 3211.09 19 D_007 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI NAVSHANTI NAGAR 4013.82 20 D_008 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI ASHA NAGAR 1899.04 21 D_009 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SIMLA NAGAR 9706.69 22 D_010 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SHIVAJI NAGAR 1841.12 23 D_015A D GIRGAUM COLABA MUMBAI SIDHDHARTH NAGAR 2189.50 Page 1 of 101 SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. -

Total List of MCGM and Private Facilities.Xlsx

MUNICIPAL CORPORATION OF GREATER MUMBAI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARIES SR SR WARD NAME OF THE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY ADDRESS NO NO 1 1 COLABA MUNICIPALMUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 1ST FLOOR, COLOBA MARKET, LALA NIGAM ROAD, COLABA MUMBAI 400 005 SABOO SIDIQUE RD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY ( 2 2 SABU SIDDIQ ROAD, MUMBAI (UPGRADED) PALTAN RD.) 3 3 MARUTI LANE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY MARUTI LANE,MUMBAI A 4 4 S B S ROAD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 308, SHAHID BHAGATSINGH MARG, FORT, MUMBAI - 1. 5 5 HEAD OFFICE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY HEAD OFFICE BUILDING, 2ND FLOOR, ANNEX BUILDING, MUMBAI - 1, 6 6 HEAD OFFICE AYURVEDIC MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY HEAD OFFICE BUILDING, 2ND FLOOR, ANNEX BUILDING, MUMBAI - 1, 7 1 SVP RD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 259, SARDAR VALLABBHAI PATEL MARG, QUARTERS, A BLOCK, MAUJI RATHOD RD, NOOR BAUG, DONGRI, MUMBAI 400 8 2 WALPAKHADI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 009 9B 3 JAIL RD. UNANI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 259, SARDAR VALLABBHAI PATEL MARG, 10 4 KOLSA MOHALLA MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 20, KOLSA STREET, KOLSA MOHALLA UNANI , PAYDHUNI 11 5 JAIL RD MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 20, KOLSA STREET, KOLSA MOHALLA UNANI , PAYDHUNI CHANDANWADI SCHOOL, GR.FLOOR,CHANDANWADI,76-SHRIKANT PALEKAR 12 1 CHANDAN WADI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY MARG,MARINELINES,MUM-002 13 2 THAKURDWAR MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY THAKURDWAR NAKA,MARINELINES,MUM-002 C PANJRAPOLE HEALTH POST, RAMA GALLI,2ND CROSS LANE,DUNCAN ROAD 14 3 PANJRAPOLE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY MUMBAI - 400004 15 4 DUNCAN RD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY DUNCAN ROAD, 2ND CROSS GULLY 16 5 GHOGARI MOHALLA MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY HAJI HASAN AHMED BAZAR MARG, GOGRI MOHOLLA 17 1 NANA CHOWK MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY NANA CHOWK, FIRE BRIGADE COMPOUND, BYCULLA 18 2 R. S. NIMKAR MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY R.S NIMKAR MARG, FORAS ROAD, 19 3 R. -

Characteristics of Diatom Communities Epiphytic on Brown Algae Padinagymnospora (Kutzing) Sonder, from Central West Coast of India

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 ResearchGate Impact Factor (2018): 0.28 | SJIF (2018): 7.426 Characteristics of Diatom Communities Epiphytic on Brown Algae Padinagymnospora (Kutzing) Sonder, from Central West Coast of India Vikrant A. Kulkarni1, Dr. Sandesh P. Jagdale2 1Department of Botany, Dapoli Urban Bank Senior Science College, Dapoli, Maharashtra, 415 712, India Email: kulkarnivikrant6[at]gmail.com 2The Principal, Dapoli Urban Bank Senior Science College, Dapoli, Maharashtra, 415 712, India Email: spjagdale[at]gmail.com Abstract: Epiphytic diatoms among marine microalgae are of special interest for their environmental, biochemical and biotechnological applications. However, seaweeds particularly from the tropics have remained unexplored for their epiphytic flora. Diatom floras associated with Padinagymnospora were evaluated for their community structure. Diatom communities were highly diversified and were represented by 53 species, observing dominant genera Navicula, Rhizosolenia, Nitzschia, Grammatophora and Caloneis from relatively less or non-polluted localities. Composition from polluted areas typically supported one community hypothesis, with dominance of Biddulphia and Licmophora. Species diversity was found to be inversely related with nutrient concentrations in ambient waters. The present study proved that epiphytic diatoms on seaweeds could serve as reliable ecological indicators. Keywords: Epiphytic Diatoms, Seaweeds, Padinagymnospora, Ecology, Bioindicators 1. Introduction Padinagymnospora, one of the predominant Phaeophyta species from the tropics, is particularly dominant along Seaweeds form a major source of organic matter in near Indian coast and has an extended growing season of about shore waters, and harbor various kinds of associated and 7 – 8 months (Dhargalkar et al., 2001). It is generally epiphytic biota (Chemello and Milazzo, 2002; Ranjitham found in mid-intertidal zones, along rocky shores and rock et al., 2008). -

Geochemical Assessment of Metal Concentrations in Mangrove Sediments Along Mumbai Coast, India

World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Geological and Environmental Engineering Vol:6, No:1, 2012 Geochemical Assessment of Metal Concentrations in Mangrove Sediments along Mumbai Coast, India Lina Fernandes, G. N. Nayak and D. Ilangovan Abstract—Two short sediment cores collected from mangrove Maharashtra, one of the important coastal states of India, is areas of Manori and Thane creeks along Mumbai coast were analysed endowed with unique mangrove diversity spread all along its for sediment composition and metals (Fe, Mn, Cu, Pb, Co, Ni, Zn, Cr 720 km coastline, distributed in about 55 estuaries in five and V). The statistical analysis of Pearson correlation matrix proved districts. Rapid developments like housing, industrialization that there is a significant relationship between metal concentration and finer grain size in Manori creek while poor correlation was and increasing population in and around Mumbai have observed in Thane creek. Based on the enrichment factor, the present resulted into degradation of most of the mangroves. In the metal to background metal ratios clearly reflected maximum present study, an attempt has been made to investigate the enrichment of Cu and Pb in Manori creek and Mn in Thane creek. mangrove sediments of Manori and Thane creek with an aim Geoaccumulation index calculated indicate that the study area is to determine the concentration as well as the vertical unpolluted with respect to Fe, Mn, Co, Ni, Zn and Cr in both the distribution pattern of selected metals in sediment and, to cores while moderately polluted with Cu and Pb in Manori creek. Based on contamination degree, both the core sediments were found understand the degree of anthropogenic influence on metal to be considerably contaminated with metals. -

Fare for Auto Rickshaws Plying Under “ Share an Autorickshaw Scheme ’’ R.T

PDFaid.Com #1 Pdf Solutions FARE FOR AUTO RICKSHAWS PLYING UNDER “ SHARE AN AUTORICKSHAW SCHEME ’’ R.T. O. Mumbai ( West Zone) Revised Fare w.e.f. 11 OCTOBER 2012 Sr. Share Autorickshaw Routes Distance Fare Payable Addl. Total Fare payable by No. ( K.M.) 33 % Fare each Passanger BANDRA 1 Bandra Rly. Stn. (W) to Hill Rd/Mount Mary 2.60 26.00 8.58 34.58 12.00. 2 Bandra Rly. Stn. (W) to Band Stand 3.60 36.00 11.88 47.88 16.00. 3 Bandra Rly. Stn. (E) to New English School, 3.80 38.00 12.54 50.54 17.00 Resolution No 10/2007 dt 21/02/2007 & revised vide Resolution No 24/2011 dt 12/05/2011 4 Bandra Rly. Stn. (E) to Government Colony, 3.20 32.00 10.56 42.56 14.00 Resolutiona No 10/2007 dt 21/02/2007 & revised vide Resolution No 24/2011 dt 12/05/2011 5 Bandra Rly. Stn. (E) to G.N. Colony, 2.20 22.00 7.26 29.26 10.00 Resolutiona No 10/2007 dt 21/02/2007 & revised vide Resolution No 24/2011 dt 12/05/2011 6 Bandra Rly. Stn. (E) to ICICI Bank Bldg, 4.00 39.00 12.87 51.87 17.00 Resolution No 57/2010 Dt 13/10/2010 7 Bandra Rly. Stn. (E) to Family Court, Resolution No 2.00 20.00 6.66 26.66 9.00 57/2010 dt 13/10/2010 8 Bandra Rly. Stn. (W) to 100 feet before, Steps 2.40 24.00 7.92 31.92 11.00 of Mount Mary Church , Resolution No 11 / 2012 Dt 20/09/2012 9 Bandra Rly.