P5537b-5544A Hon Aaron Stonehouse; Hon Pierre Yang; Hon Martin Pritchard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Add Your Voice If You Want a Choice

Who Are We Mr Nick GOIRAN PERTH UPPER Unit 2, 714 Ranford Road, Go Gentle Go Gentle Australia, founded by Andrew Denton, is an SOUTHERN RIVER WA 6110 Australia expert advisory and health promotion charity for a better HOUSE MEMBERS Ph: (08) 9398 3800 Mr Simon O’BRIEN conversation around death, dying and end of life choices. North Metropolitan 904 Canning Highway, Our campaigning efforts in Victoria in 2017 provided Mr Peter COLLIER CANNING BRIDGE WA 6153, or Shop 23A, Warwick Grove Corner Beach PO Box 919, CANNING BRIDGE WA 6153 IF YOU WANT critical assistance to those in the Victorian parliament Road and Erindale Road, WARWICK WA E: [email protected] who fought for and ultimately succeeded in the historic 6024, or PO Box 2606, WARWICK WA 6024 Ph: (08) 9364 4277 E: [email protected] passing of Voluntary Assisted Dying legislation. Mr Aaron STONEHOUSE A CHOICE, Ph: (08) 9203 9588 Level 1, Sterling House, In Western Australia, we are supporting a campaign to Ms Alannah MacTIERNAN 8 Parliament Place, Unit 1, 386 Wanneroo Road, WEST PERTH WA 6005 see parliament pass a Voluntary Assisted Dying law WESTMINSTER WA 6061 E: [email protected] ADD YOUR VOICE similar to Victoria’s. E: [email protected] Ph: (08) 9226 3550 Ph: (08) 6552 6200 Mr Pierre YANG Please help us to be heard Mr Michael MISCHIN Unit 1, 273 South Street, HILTON WA TELL YOUR MPs YOU WANT THEM TO SUPPORT Unit 2, 5 Davidson Terrace, 6163 or PO Box 8166, Hilton WA 6163 THE VOLUNTARY ASSISTED DYING BILL. -

Hon Daniel James Caddy, MLC (Member for North Metropolitan)

PARLIAMENT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA INAUGURAL SPEECH Hon Daniel James Caddy, MLC (Member for North Metropolitan) Legislative Council Address-in-Reply Tuesday, 25 May 2021 Reprinted from Hansard Legislative Council Tuesday, 25 May 2021 ____________ ADDRESS-IN-REPLY Motion Resumed from 13 May on the following motion moved by Hon Pierre Yang — That the following address be presented to His Excellency the Honourable Kim Beazley, Companion of the Order of Australia, Governor in and over the state of Western Australia and its dependencies in the Commonwealth of Australia — May it please Your Excellency: We, the members of the Legislative Council of the Parliament of Western Australia in Parliament assembled, beg to express our loyalty to our most gracious sovereign and thank Your Excellency for the speech you have been pleased to deliver to Parliament. HON DAN CADDY (North Metropolitan) [5.03 pm]: It is important to me that the first words I utter in this place are to acknowledge the traditional owners of the land on which this place stands, the Whadjuk people of the proud Noongar nation. I pay my respects to their elders past, present and emerging. This land is Whadjuk boodja—always was and always will be. I shared a flight to Canberra with the Governor nearly 15 years ago. We sat, just the two of us, at a table on the government jet. It was an incredible conversation. Then later that year, I was dropping something off at his office at Parliament House in Canberra and I asked him a simple question about his time in politics. -

P6057d-6069A Hon Martin Pritchard; Hon Helen Morton; Hon Alanna Clohesy; Hon Phil Edman; Hon Darren West; Hon Adele Farina; Hon Sue Ellery

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Thursday, 10 September 2015] p6057d-6069a Hon Martin Pritchard; Hon Helen Morton; Hon Alanna Clohesy; Hon Phil Edman; Hon Darren West; Hon Adele Farina; Hon Sue Ellery METHAMPHETAMINE USE Motion HON MARTIN PRITCHARD (North Metropolitan) [10.05 am] — without notice: I move the motion that has been distributed in my name — That this house — (a) notes that, after seven years of a Liberal–National government, Western Australia now has the highest rate of methamphetamine use in the country; and (b) calls on the government to work collaboratively with the opposition and all stakeholders to develop a holistic approach that gives equal weight to — (i) reducing the demand for methamphetamine; (ii) reducing the harm caused by methamphetamine; and (iii) reducing the supply of methamphetamine. I move this motion in the hope of trying to raise awareness of the damage that methamphetamine, particularly in the form of ice, is doing to our communities, our families and the poor devils who are trapped in the cycle of dependence on this substance. The facts are that a conservative determination of the use of methamphetamine, mostly in the form of ice, in Western Australia is about 3.8 per cent. That figure nationally is 2.1 per cent. The problem here is some 80 per cent worse than the national average. I have not raised this matter as a point-scoring exercise, as it is too important an issue for partisan politics, but that is not to say that there will not be any criticism of the government in my speech. -

Pdf (572.33Kb)

Dear Mr McCusker, Please find attached Enhancing Democracy in Western Australia, my submission to the review of the Western Australian Legislative Council electoral system. I am happy for it to be made public. Yours sincerely, Chris Curtis Enhancing Democracy in Western Australia Chris Curtis May 2021 The manufactured hysteria that greeted Ricky Muir’s election to the Senate and that ultimately led to the Turnbull government’s rigging the Senate voting system to favour the Greens over the micro-parties is getting an encore performance with the election of Wilson Tucker in Western Australia, despite the unremarked-upon election in both jurisdictions of many more candidates of major parties from even lower primary votes and with the added twist that most members of the panel established to investigate the matter have already endorsed, even promoted, the hysteria (https://insidestory.org.au/an-affront-to-anyone-who- believes-in-democracy/). While it is clear from this fact that submissions in support of logic and democracy have already been ruled out of consideration, it is worthwhile putting them on the public record for future historians to refer to and so that more reasonable politicians can revisit the issue if the hysteria dies down. Enhancing Democracy in Western Australia 2 Contents Purpose - - - - - - - - - - 3 Summary - - - - - - - - - - 3 1. Principles - - - - - - - - - - 5 2. The Single Transferable Vote - - - - - - - 6 3. The Irrational Complaints - - - - - - - 11 4. Party Preferences - - - - - - - - - 15 5. Imposing a Party List System - - - - - - - 17 6. The Value of Group Voting Tickets - - - - - - 18 7. The Real Issue and the Solution - - - - - - - 20 8. Personal How-to-Vote Website - - - - - - - 22 9. -

Parliamentary Debates (HANSARD)

Parliamentary Debates (HANSARD) FORTY-FIRST PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION 2021 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Tuesday, 3 August 2021 Legislative Council Tuesday, 3 August 2021 THE PRESIDENT (Hon Alanna Clohesy) took the chair at 2.00 pm, read prayers and acknowledged country. SPRING SITTINGS Statement by President THE PRESIDENT (Hon Alanna Clohesy) [2.03 pm]: Welcome back, members. I hope you have had an opportunity to refresh and I wish you all a productive next few months. BILLS Assent Message from the Governor received and read notifying assent to the following bills — 1. Building and Construction Industry (Security of Payment) Bill 2021. 2. Supply Bill 2021. 3. Sunday Entertainments Repeal Bill 2021. 4. Corruption, Crime and Misconduct Amendment Bill 2021. FRANK WISE INSTITUTE OF TROPICAL AGRICULTURE Statement by Minister for Agriculture and Food HON ALANNAH MacTIERNAN (South West — Minister for Agriculture and Food) [2.05 pm]: Members, 10 days ago we gathered at the Frank Wise Institute of Tropical Agriculture in Kununurra to celebrate three-quarters of a century of agricultural research in the East Kimberley—a significant milestone for agricultural research and development, and for development in the Ord. Descendants of those who were central to the establishment of the research centre, including former Premier Frank Wise and the Durack family, as well as farmers and civic leaders, paid testimony to the vision and fortitude of those who helped to realise the potential of the fertile landscape. The Kimberley Research Station was established in 1946 as a joint state and commonwealth initiative, staffed by the CSIRO and the Western Australian Department of Agriculture. -

P323b-330A Hon Pierre Yang; Hon Alannah Mactiernan; Hon Robin Scott; Hon Martin Pritchard; Hon Tim Clifford; Hon Peter Collier; Hon Laurie Graham

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Thursday, 14 February 2019] p323b-330a Hon Pierre Yang; Hon Alannah MacTiernan; Hon Robin Scott; Hon Martin Pritchard; Hon Tim Clifford; Hon Peter Collier; Hon Laurie Graham FUTURE BATTERY INDUSTRY STRATEGY Motion HON PIERRE YANG (South Metropolitan) [11.34 am] — without notice: I move — That the house commend the McGowan government for launching its “Future Battery Industry Strategy Western Australia” and its focus to diversify the Western Australian economy and create jobs. It gives me great pleasure to move this motion. Western Australia is blessed with a strong mining and resources sector that centres around iron ore, gold and petroleum. In fact, Western Australia contributes about half of Australia’s overall exports in this sector. It is a privileged position for us to be in. The mining and resources sector contributes enormously to the Western Australian economy, and thanks should be given to the hardworking men and women in that industry. At the same time, we should not forget or ignore the fact that the mining and resources sector is cyclical in nature. For instance, iron ore is the single largest contributor to our exports, accounting for $61.7 billion in the 2017–18 financial year. That represents 54 per cent of our overall sales of mineral commodities. When the price of iron ore was skyrocketing—it was at historic highs in 2007, 2008, 2010, 2011 and 2013, during the time of the Barnett government—we were doing really well as a state, because the price was soaring towards $US200 a dry metric tonne. However, when the price collapsed to just over $US40 a tonne, to say that we were struggling as a state is an understatement. -

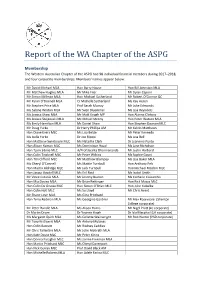

Report of the WA Chapter of the ASPG

Report of the WA Chapter of the ASPG Membership The Western Australian Chapter of the ASPG had 98 individual financial members during 2017–2018, and four corporate memberships. Members’ names appear below: Mr David Michael MLA Hon Barry House Hon Bill Johnston MLA Mr Matthew Hughes MLA Mr Mike Filer Mr Dylan Caporn Mr Simon Millman MLA Hon Michael Sutherland Mr Robert O’Connor QC Mr Kyran O’Donnell MLA Cr Michelle Sutherland Ms Kay Heron Mr Stephen Price MLA Prof Sarah Murray Mr Luke Edmonds Ms Sabine Winton MLA Mr Sven Bluemmel Ms Lisa Reynders Ms Jessica Shaw MLA Mr Matt Keogh MP Hon Alanna Clohesy Ms Jessica Stojkovski MLA Mc Mihael McCoy Hon Peter Watson MLA Ms Emily Hamilton MLA Mr Daniel Shaw Hon Stephen Dawson MLC Mr Doug Yorke Dr Harry Phillips AM Mr Kelvin Matthews Hon Diane Evers MLC Ms Lisa Belde Mr Peter Kennedy Ms Izella Yorke Dr Joe Ripepi Ms Lisa Bell Hon Matthew Swinbourn MLC Ms Natasha Clark Dr Jeannine Purdy Hon Alison Xamon MLC Ms Dominique Hoad Ms Jane Nicholson Hon Tjorn Sibma MLC A/Prof Jacinta Dharmananda Mr Justin Harbord Hon Colin Tincknell MLC Mr Peter Wilkins Ms Sophie Gaunt Hon Tim Clifford MLC Mr Matthew Blampey Ms Lisa Baker MLA Ms Cheryl O’Connell Ms Mattie Turnbull Hon Anthony Fels Hon Martin Aldridge MLC Mr Jack Turnbull Hon Michael Mischin MLC Hon Jacqui Boydell MLC Ms Eril Reid Ms Isabel Smith Mr Vince Catania MLA Mr Jeremy Buxton Ms Catharin Cassarchis Hon Mia Davies MLA Mr Brian Rettinger Hon Rick Mazza MLC Hon Colin De Grussa MLC Hon Simon O’Brien MLC Hon John Kobelke Hon Colin Holt MLC Ms Su Lloyd -

P4947d-4962A Hon Liz Behjat; Hon Martin Pritchard ESTIMATES OF

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Tuesday, 11 August 2015] p4947d-4962a Hon Liz Behjat; Hon Martin Pritchard ESTIMATES OF REVENUE AND EXPENDITURE Consideration of Tabled Papers Resumed from an earlier stage of the sitting. HON LIZ BEHJAT (North Metropolitan) [5.10 pm]: I was earlier setting the scene for my contribution to this budget debate, and I had said that I wanted to concentrate on science, technology, engineering and mathematics and outline their importance. I will continue with the background to the important role science plays in everything we do and how we sometimes do not think about things as being science. Human beings, as we know, are very curious creatures who seek out explanations based on how and why things function the way they do. This predisposition is not a new phenomenon; indeed, it is as ancient as our species itself. When our primeval human ancestors felt the need to explain why thunder, sea storms, fire and wind happened, they ascribed these natural phenomena, as we know them today, to a special deity. There was a god of thunder or a goddess of fire; they were really not across what those issues were. Today, as we know, we reject these explanations as being just that—primeval. But the point we miss is that the invention of these deities by our pre- modern ancestors was the result of the same scientific curiosity that took Neil Armstrong to the moon in 1969. I do not know whether any members saw last night’s edition of Q&A, but Colonel Chris Hadfield was one of the guests and spoke about his time on the space station. -

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL WEDNESDAY, 2 JUNE 2021 1.00Pm

12 Business Program LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL WEDNESDAY, 2 JUNE 2021 1.00pm Prayers Acknowledgement of Country ORDER OF BUSINESS Condolence Motions Petitions Statements by Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries Minister for Agriculture and Food Papers for Tabling President Notice of Questions Notices of Motions to Introduce Bills Notices of Motions for Disallowance Notices of Motions Hon Tjorn Sibma Hon Dr Sally Talbot Hon Dan Caddy Motions without Notice Leader of the House 1.15pm Motions on Notice 3.15pm Committee Reports 4.30pm Questions without Notice 5.00pm Orders of the Day 6.20pm Members’ Statements 7.00pm House adjourns The business listed for today’s sitting and sequence in which it is to be considered may be altered by the House without notice. To see what is currently being debated in the course of today’s sitting please see the electronic Business Program at: www.parliament.wa.gov.au/WebCMS/WebCMS.nsf/content/legislative-council-live-broadcast-lc 2 MOTIONS ON NOTICE 1. Statutory Powers of the Attorney General (Notice given 27 May 2021) Hon Nick Goiran: To move — That this House — (a) expresses its deep regret at the deaths of Aishwarya Aswath and Cohen Fink and tenders its profound sympathy to members of their respective families in their bereavement; (b) notes that section 22(1)(d) of the Coroners Act 1996 empowers the Attorney General to direct the coroner, that holds jurisdiction to investigate a death, to hold an inquest if the death appears to be a Western Australian death; (c) further notes that the Attorney General has declined to exercise this power of direction; and (d) calls on the Attorney General to: (i) urgently reconsider his decision not to direct that inquests occur in these two cases; and (ii) outline the criteria by which he determines when and for whom he will utilise this statutory power. -

P264b-285A Hon Martin Pritchard; Hon Diane Evers; Hon Colin Holt; Hon Simon O'brien

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL — Thursday, 6 May 2021] p264b-285a Hon Martin Pritchard; Hon Diane Evers; Hon Colin Holt; Hon Simon O'Brien ADDRESS-IN-REPLY Motion Resumed from 5 May on the following motion moved by Hon Pierre Yang — That the following address be presented to His Excellency the Honourable Kim Beazley, Companion of the Order of Australia, Governor in and over the state of Western Australia and its dependencies in the Commonwealth of Australia — May it please Your Excellency: We, the members of the Legislative Council of the Parliament of Western Australia in Parliament assembled, beg to express our loyalty to our most gracious sovereign and thank Your Excellency for the speech you have been pleased to deliver to Parliament. HON MARTIN PRITCHARD (North Metropolitan) [12.35 pm]: I seek to adjourn my contribution to the Address-In-Reply and continue my remarks at a later stage of today’s sitting. [Leave granted for the member’s speech to be continued at a later stage of the sitting.] HON DIANE EVERS (South West) [12.36 pm]: Four years ago, at the 2017 election, I was given the opportunity to make some positive change. I took the role seriously, learnt quickly and did my best to do some good. I listened to people, travelled throughout the south west and found the issues people felt were not being heard or were being ignored. I also found issues that were so big that people felt powerless to even speak out. I soon realised that my role was not just to speak in Parliament on behalf of the people who are not being listened to, but also for those who had not found their voice and those who did not have a voice. -

Hon Martin Pritchard, MLC (Member for North Metropolitan Region)

PARLIAMENT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA INAUGURAL SPEECH Hon Martin Pritchard, MLC (Member for North Metropolitan Region) Legislative Council Loan Bill 2015 Tuesday, 19 May 2015 Reprinted from Hansard Legislative Council Tuesday, 19 May 2015 ____________ LOAN BILL 2015 Second Reading HON MARTIN PRITCHARD (North Metropolitan) [5.08 pm]: Thank you, Madam Deputy President. Firstly, I would like to take the opportunity to acknowledge and recognise the traditional owners and custodians of the land on which we meet. It is with great humility that I rise to speak today, this being my first real contribution to this place. May I start by expressing my gratitude to the President, to the Clerks, and to all the parliamentary staff, for their assistance and for making me feel so welcome since my swearing-in. First and foremost, I would like to thank the electors of North Metropolitan Region for their continuing support of the Labor Party, and, in this particular instance, of me personally. I will work hard to try and justify the trust that they have placed in me. Before I speak a bit about myself and the aspirations that I hold, I would like to acknowledge the work of those who have recently held this position before me. I have had the pleasure of knowing and collaborating with Hon Edmund Dermer and Hon Ljiljanna Ravlich for nearly 20 years. During that time, I have seen the tremendous contributions that both of these fine individuals made to the lives of all Western Australians through their work in this place. I can only hope that I can emulate their drive and commitment in the years to come. -

Western Australian State Election 2013

WESTERN AUSTRALIAN STATE ELECTION 2013 ANALYSIS OF RESULTS by Antony Green for the Western Australian Parliamentary Library and Information Services Election Papers Series No. 1/2013 2013 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent from the Librarian, Western Australian Parliamentary Library, other than by Members of the Western Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Western Australian Parliamentary Library. Western Australian Parliamentary Library Parliament House Harvest Terrace Perth WA 6000 ISBN 978-0-9875969-0-1 May 2013 Related Publications 2011 Redistribution Western Australia – Analysis of Final Electoral Boundaries by Antony Green. Election paper series 1/2011. Western Australian State Election 2008 Analysis of Results by Antony Green. Election paper series 1/2009. 2007 Electoral Distribution Western Australia: Analysis of Final Boundaries Election papers series 2/2007 Western Australian State Election 2005 - Analysis of Results by Antony Green. Election papers series 2/2005. 2003 Electoral Distribution Western Australia: Analysis of Final Boundaries Election papers series 2/2003. Western Australian State Elections 2001 by Antony Green. Election papers series 2/2001. Western Australian State Elections