Launch of Peter Coleman's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Introduction to the Life and Work of Amy Witting

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship... 'GOLD OUT OF STRAW': AN INTRODUCTION TO THE LIFE AND WORK OF AMY WITTING Yvo nne Miels - Flin ders University It is rather unusual for anyone to be in their early seventies before being recognised as a writer of merit. In this respect Amy Wining must surely be unique amongst Australian writers. Although she has been writing all her life, she was 71 when her powerful novel I for Isabel was published, in late 1989. This novel attracted considerable critical attention, and since then most of the backlog of stories and poetry written over a lifetime have been published. The 1993 Patrick White Award followed and she became known to a wider readership. The quality and sophistication of her work, first observed over fifty years ago, has now been generally acknowledged. Whilst Witting has been known to members of the literary community in New South Wales for many years, her life and work have generally been something of a literary mystery. Like her fictional character Fitzallan, the ·undiscovered poet' in her first novel Th e Visit ( 1977). her early publications were few, and scattered in Australian literary journals and short-story collections such as Coast to Coast. While Fitzallan's poetry was 'discovered' forty years after his death, Witting's poetry has been discovered and published, but curiously, it is absent from anthologies. For me, the 'mystery' of Amy Witting deepened when the cataloguing in-publication details in a rare hard-back copy of Th e Visit revealed the author as being one Joan Levick. -

Dilemmas of Defending Dissent: the Dismissal of Ted Steele from the University of Wollongong

AUSTRALIAN UNIVERSITIES REVIEW Dilemmas of Defending Dissent: The Dismissal of Ted Steele from the University of Wollongong BRIAN MARTIN When the University of Wollongong decided to sack a self-styled whistleblower, some colleagues and unionists had mixed emotions. Brian Martin explains the difficult processes that followed. On 26 February 2001, Ted Steele was summarily dismissed demic freedom, most parties to the conflict were more con- from his tenured post of Associate Professor in the Department cerned with winning specific battles. The Steele case shows of Biological Sciences at the University of Wollongong, fol- how difficult it is to operationalise global concepts of justice lowing his contentious public comments about ‘soft marking,’ and freedom. namely lower standards especially for full-fee-paying foreign I describe the Australian and Wollongong context of the dis- students. The dismissal sparked a huge outcry in academic cir- missal, then look at Steele’s actions and their interpretations cles and beyond, where it was widely seen as an attack on aca- and finally assess the strategies adopted by the key players demic freedom. The case soon became the most prominent of from the point of view of defending dissent. its sort in Australia since the dismissal of Professor Sydney Orr from the University of Tasmania in 1956, itself a landmark in DISSENT IN AUSTRALIAN UNIVERSITIES the history of Australian higher education. What is the state of dissent in Australian universities? This Few cases are as simple as they appear on the surface. The question is surprisingly difficult to answer. There is quite a lot Steele dismissal can be approached from a bewildering range of dissent expressed in both professional and public fora, with of perspectives, including Steele’s personality and history, no difficulties anticipated or encountered; at the same time, the accuracy and legitimacy of Steele’s public statements, there is quite a lot of suppression and inhibition of dissent. -

Mongrel Media Presents a Film by Adam Elliot

Mongrel Media Presents A Film by Adam Elliot (92 min., Australia, 2009) Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html Synopsis The opening night selection of the 2009 Sundance Film Festival and in competition at the 2009 Berlin Generation 14plus, MARY AND MAX is a clayography feature film from Academy Award® winning writer/director Adam Elliot and producer Melanie Coombs, featuring the voice talents of Toni Collette, Phillip Seymour Hoffman, Barry Humphries and Eric Bana. Spanning 20 years and 2 continents, MARY AND MAX tells of a pen-pal relationship between two very different people: Mary Dinkle (Collette), a chubby, lonely 8-year-old living in the suburbs of Melbourne, Australia; and Max Horovitz (Hoffman), a severely obese, 44-year-old Jewish man with Asperger’s Syndrome living in the chaos of New York City. As MARY AND MAX chronicles Mary’s trip from adolescence to adulthood, and Max’s passage from middle to old age, it explores a bond that survives much more than the average friendship’s ups-and-downs. Like Elliot and Coombs’ Oscar® winning animated short HARVIE KRUMPET, MARY AND MAX is both hilarious and poignant as it takes us on a journey that explores friendship, autism, taxidermy, psychiatry, alcoholism, where babies come from, obesity, kleptomania, sexual differences, trust, copulating dogs, religious differences, agoraphobia and many more of life’s surprises. -

Samuel Griffith Society Proceedings Vol 2

Proceedings of the Second Conference of The Samuel Griffith Society Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Two The Windsor Hotel, Melbourne; 30 July - 1 August 1993 Copyright 1993 by The Samuel Griffith Society. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Foreword (P4) John Stone Foreword Dinner Address (P5) The Hon. Jeff Kennett, MLA; Premier of Victoria The Crown and the States Introductory Remarks (P14) John Stone Introductory Chapter One (P15) Dr Frank Knopfelmacher The Crown in a Culturally Diverse Australia Chapter Two (P18) John Hirst The Republic and our British Heritage Chapter Three (P23) Jack Waterford Australia's Aborigines and Australian Civilization: Cultural Relativism in the 21st Century Chapter Four (P34) The Hon. Bill Hassell Mabo and Federalism: The Prospect of an Indigenous People's Treaty Chapter Five (P47) The Hon. Peter Connolly, CBE, QC Should Courts Determine Social Policy? Chapter Six (P58) S E K Hulme, AM, QC The High Court in Mabo Chapter Seven (P79) Professor Wolfgang Kasper Making Federalism Flourish Chapter Eight (P84) The Rt. Hon. Sir Harry Gibbs, GCMG, AC, KBE The Threat to Federalism Chapter Nine (P88) Dr Colin Howard Australia's Diminishing Sovereignty Chapter Ten (P94) The Hon. Peter Durack, QC What is to be Done? Chapter Eleven (P99) John Paul The 1944 Referendum Appendix I (P113) Contributors Appendix II (P116) The Society's Statement of Purposes Published 1993 by The Samuel Griffith Society P O Box 178, East Melbourne Victoria 3002 Printed by: McPherson's Printing Pty Ltd 5 Dunlop Rd, Mulgrave, Vic 3170 National Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data: Proceedings of The Samuel Griffith Society Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume Two ISBN 0 646 15439 7 Foreword John Stone Copyright 1993 by The Samuel Griffith Society. -

Friends Newsletter

FRIENDS OF THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA INC. WINTER 2016 Meet the Volunteer MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR Dear Friends Thank you to the many Friends who responded with sustained support to the sad news that June 2016 sees the final print issue of the National Library of Australia Magazine. Your decision to remain Friends is both heartening and encouraging. We continue to support the Library as it maintains its essential contribution to the vitality of Australian culture and heritage under increasingly Roger, how long have you been a volunteer at the Library? tight fiscal constraints. I joined the Library as a volunteer 15 years ago, beginning I was recently in the Treasures Gallery and fell into when the blockbuster exhibition, Treasures from the World’s conversation with a gentleman who had travelled from Great Libraries, was launched. Canada just to see items in the collection. He was more Tell us about your career prior to joining the Library’s than excited to be there; although he uses Trove and other Volunteer Program. NLA digital records back in Nova Scotia, the opportunity Part of my early career was spent in Tanzania, with the Australian to see the tangible historical documents was inspiring for Volunteers Abroad scheme. I taught economics and also him. Australians cherish their trips to foreign museums and assisted with adult education. When I moved to Canberra in galleries, and this conversation reminded me that we have 1970, I soon joined the newly created Department of Aboriginal much of inestimable cultural and historical value right here Affairs. For much of the two decades that followed, I was a policy at the NLA. -

Academic Freedom and Institutional Autonomy in American and Australian Universities: a Twenty-First Century Dialogue and a Call to Leaders

ACADEMIC FREEDOM AND INSTITUTIONAL AUTONOMY IN AMERICAN AND AUSTRALIAN UNIVERSITIES: A TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY DIALOGUE AND A CALL TO LEADERS PATRICK D. PAUKEN† BOWLING GREEN STATE UNIVERSITY, USA Within the context of academic freedom and institutional autonomy, and ultimately with respect to the important roles played by university leaders, this article explores the current dialogue among American and Australian university players, both individual and institutional, as those players search for, develop, define, modify, and proclaim their respective voices and messages, particularly in a world where the role and position of universities are changing. I INTRODUCTION In 1964, Marvin L. Pickering, a public school teacher in Illinois, wrote a letter to the editor of a local newspaper criticising his board of education for the board’s appropriation of funds and its handling of two failed tax levy campaigns. The board countered with accusations that the statements in the letter were false and had a negative impact on the efficient operation of the schools. The board of education then fired Pickering.1 Meanwhile, in Australia, administrators at the University of Sydney vetoed the appointment of philosophy professor Frank Knopfelmacher after he exposed Communist infiltration in some of the academic units at the University of Melbourne.2 Fast forward to 2005. Ward Churchill, faculty member in the University of Colorado’s ethnic studies department, came under significant fire on campus and throughout the United States for his written and spoken arguments that, among other comments, the victims of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, were ‘little Eichmanns’ and presumably deserved their fate. -

With the End of the Cold War, the Demise of the Communist Party Of

A Double Agent Down Under: Australian Security and the Infiltration of the Left This is the Published version of the following publication Deery, Phillip (2007) A Double Agent Down Under: Australian Security and the Infiltration of the Left. Intelligence and National Security, 22 (3). pp. 346-366. ISSN 0268-4527 (Print); 1743-9019 (Online) The publisher’s official version can be found at Note that access to this version may require subscription. Downloaded from VU Research Repository https://vuir.vu.edu.au/15470/ A Double Agent Down Under: Australian Security and the Infiltration of the Left PHILLIP DEERY Because of its clandestine character, the world of the undercover agent has remained murky. This article attempts to illuminate this shadowy feature of intelligence operations. It examines the activities of one double agent, the Czech-born Maximilian Wechsler, who successfully infiltrated two socialist organizations, in the early 1970s. Wechsler was engaged by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation. However, he was ‘unreliable’: he came in from the cold and went public. The article uses his exposés to recreate his undercover role. It seeks to throw some light on the recruitment methods of ASIO, on the techniques of infiltration, on the relationship between ASIO and the Liberal Party during a period of political volatility in Australia, and on the contradictory position of the Labor Government towards the security services. In the post-Cold War period the role of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) no longer arouses the visceral hostility it once did from the Left. The collapse of communism found ASIO in search of a new raison d’étre. -

Theatre Australia Historical & Cultural Collections

University of Wollongong Research Online Theatre Australia Historical & Cultural Collections 11-1977 Theatre Australia: Australia's magazine of the performing arts 2(6) November 1977 Robert Page Editor Lucy Wagner Editor Bruce Knappett Associate Editor Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theatreaustralia Recommended Citation Page, Robert; Wagner, Lucy; and Knappett, Bruce, (1977), Theatre Australia: Australia's magazine of the performing arts 2(6) November 1977, Theatre Publications Ltd., New Lambton Heights, 66p. https://ro.uow.edu.au/theatreaustralia/14 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Theatre Australia: Australia's magazine of the performing arts 2(6) November 1977 Description Contents: Departments 2 Comments 4 Quotes and Queries 5 Letters 6 Whispers, Rumours and Facts 62 Guide, Theatre, Opera, Dance 3 Spotlight Peter Hemmings Features 7 Tracks and Ways - Robin Ramsay talks to Theatre Australia 16 The Edgleys: A Theatre Family Raymond Stanley 22 Sydney’s Theatre - the Theatre Royal Ross Thorne 14 The Role of the Critic - Frances Kelly and Robert Page Playscript 41 Jack by Jim O’Neill Studyguide 10 Louis Esson Jess Wilkins Regional Theatre 12 The Armidale Experience Ray Omodei and Diana Sharpe Opera 53 Sydney Comes Second best David Gyger 18 The Two Macbeths David Gyger Ballet 58 Two Conservative Managements William Shoubridge Theatre Reviews 25 Western Australia King Edward the Second Long Day’s Journey into Night Of Mice and Men 28 South Australia Annie Get Your Gun HMS Pinafore City Sugar 31 A.C.T. -

Origins of the Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security

Origins of the Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security CJ Coventry LLB BA A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Research) School of Humanities and Social Sciences UNSW Canberra at ADFA 2018 i Table of Contents Acknowledgements iii Introduction & Methodology 1 Part I: ASIO before Whitlam 9 Chapter One: The creation of ASIO 9 Chapter Two: Bipartisan anti-communism 23 Chapter Three: ASIO’s anti-radicalism, 1950-1972 44 Part II: Perspectives on the Royal Commission 73 Chapter Four: Scholarly perspectives on the Royal Commission 73 Chapter Five: Contemporary perspectives on ASIO and an inquiry 90 Part III: The decision to reform 118 Chapter Six: Labor and terrorism 118 Chapter Seven: The decision and announcement 154 Part IV: The Royal Commission 170 Chapter Eight: Findings and recommendations 170 Conclusion 188 Bibliography 193 ii Acknowledgements & Dedication I dedicate this thesis to Rebecca and our burgeoning menagerie. Most prominently of all I wish to thank Rebecca Coventry who has been integral to the writing of this thesis. Together we seek knowledge, not assumption, challenge, not complacency. For their help in entering academia I thank Yunari Heinz, Anne-Marie Elijah, Paul Babie, the ANU Careers advisors, Clinton Fernandes and Nick Xenophon. While writing this thesis I received help from a number of people. I acknowledge the help of Lindy Edwards, Toni Erskine, Clinton Fernandes, Ned Dobos, Ruhul Sarkar, Laura Poole-Warren, Kylie Madden, Julia Lines, Craig Stockings, Deane-Peter -

Chapter 11 the Sydney Disturbances

Chapter 11 The Sydney Disturbances URING the twenty years from 1965, the philosophy depart- ment at Sydney University was rent by a series of bitter left- Dright disputes. Such fights — or rather, the same fight in many instantiations — were common enough in humanities depart- ments in the period. The unique virulence of the one at Sydney, which eventually led to a split into two departments, was due not only to the strength of the left, which was a frequent occurrence elsewhere, but to the determination not to give way of the leading figures of the right, David Armstrong and David Stove. Armstrong and Stove, as we saw in chapter 2, were students of John Anderson in the late 1940s, and ones of unusually independent mind. Armstrong had early success. He went for postgraduate work to Oxford, where the linguistic philosophy then current made only a limited impression on his Andersonian interest in the substantial questions of classical philosophy. He recalled attending a seminar by the leading linguistic philosophers Strawson and Grice. Grice, I think it was, read very fast a long paper which was completely unintelligible to me. Perhaps others were having difficulty also because when the paper finished there was a long, almost religious, hush in the room. Then O.P. Wood raised what seemed to be a very minute point even by Oxford standards. A quick dismissive remark by Grice and the room settled down to its devotions again. At this point a Canadian sitting next to me turned and said, ‘Say, what is going on here?’ I said, ‘I’m new round here, and I don’t know the rules of this game. -

Collection Name

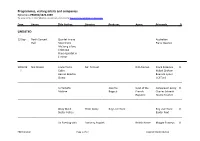

Programmes, visiting artists and companies Ephemera PR8492/1870-1899 To view items in the Ephemera collection, contact the State Library of Western Australia Date Venue Title Author Director Producer Agent Principals D UNDATED 23 Sep Perth Concert Quartet in one Australian Hall Movement Piano Quartet My Song is love Unknown Piano Quartet in C minor 1890-95 Not Stated Uncle Tom's Mr. Trimnel N.D.Aikman Frank Bateman 0 ? Cabin. Mabel Graham Harriet Beecher Beatrice Lyster Stowe J.Clifford ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Le Tartuffe Jean De Govt of the Genevieve Leomy 0 Moliere Regault French Charles Schmitt Republic Giselle Tourtet ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Betty Blokk- Peter Batey Reg Livermore Reg Livermore 0 Buster Follies Baxter Funt ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ An Evening with Anthony Asquith British Home Margot Fonteyn 0 PR8492/UND Page 1 of 19 Copyright SLWA ©2011 Programmes, visiting artists and companies Ephemera PR8492/1870-1899 To view items in the Ephemera collection, contact the State Library of Western Australia Date Venue Title Author Director Producer Agent Principals D the Royal Ballet Entertainment Rudolf Nureyev Ltd ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Fabian Lee Gordon Lee Gordon -

On STAGE WA MARITIME MUSEUM FREMANTLE 16.02.2019—09.06.2019 CONTENTS

LEARNING RESOURCE KIT WA MARITIME MUSEUM presents A TOURING EXHIBITION BY ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE AND THE AUSTRALIAN MUSIC VAULT on STAGE WA MARITIME MUSEUM FREMANTLE 16.02.2019—09.06.2019 CONTENTS: Welcome How to use this Resource Section 1 - What is an Exhibition? 1.1. Activity Introduction 1.2. Prezi – What is an Exhibition? 1.3. Types of Exhibition Spaces 1.4. The ACM Collection 1.5. Acquiring Artefacts and Artworks 1.6. Conservation of Artworks and Artefacts 1.7. ACM on Display 1.8. Activity – Who works in the team? 1.9. The Collections Team 1.10. Activity – The Exhibition of Me Section 2 – All Things Kylie 2.1. Introduction 2.2. Prezi – Kylie Career Overview 2.3. Video – Kylie – the curator’s insight 2.4. Activity – Visiting the Kylie on Stage Exhibition live or online Section 3 – Designing an Icon 3.1. What makes an Icon? 3.2. Interpreting a Song 3.3. Activity – Interpreting a Song 3.4. Garment Design Elements and Principles 3.5. Activity – Design Elements and Principles 3.6. Activity – Design Analysis Activity 3.7. Activity – Mood Board Activity 3.8. Activity – Designing a Costume 3.9. Activity – Making a Costume Appendix A – Offer of Donation Form Appendix B – Condition Report - Kylie Costume Appendix C – ACM Exhibitions Appendix D – Catalogue Worksheet Appendix E – Condition Report – Blank Appendix F – Elements and Principles Template Novice Appendix G – Elements and Principles Template Advanced Appendix H – Croquis Templates Curriculum Links Credits WELCOME Thank-you for downloading the Kylie on Stage Learning Resources. We hope you and your students enjoy learning about collections, exhibitions, music and costumes and of course Kylie Minogue as much as us! Kylie on Stage is a major free exhibition celebrating magical moments from Kylie’s highly successful concert tours around Australia.