"Sowing Seeds in Lines"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fressingfield Neighbourhood Development Plan Consultation Statement July 2019

Consultation Statement July 2019 Fressingfield Neighbourhood Development Plan Consultation Statement July 2019 Fressingfield Neighbourhood Development Plan Reg 16 Submission Version Consultation Statement July 2019 Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. Context for this Neighbourhood Development Plan 6 3. Designation of the Neighbourhood Area 8 4. Community Engagement Stages 8 5. Communication 24 6. Conclusion 25 Appendices: 26 Appendix A – Neighbourhood Plan Steering Group Terms of Reference Appendix B – Community Engagement and Consultation Plan Appendix C - Application for Neighbourhood Plan Area Designation Appendix D- Decision Notice for Neighbourhood Plan Area Designation Appendix E - Write-up of ‘Refreshing Fressingfield’ Questionnaire Appendix F- Write-up of Steering Group Initial Scoping Workshop Appendix G - Write-up of Group Consultations Appendix H – Write-up of Stradbroke High School Youth Event Appendix I – Write-up from Year 6 Fressingfield Primary School Appendix J – Write-up from Policy Ideas Exhibitions 2 Consultation Statement July 2019 Appendix K – On-line survey results Appendix L – Write-up from Landowner Session, March 2019 Appendix M – Consultation Publicity Appendix N - List of consultees for Pre-Submission (REG14) Consultation Appendix O – Notification emails: • Owners of Non-Designated Heritage Assets • Owners of Local Green Spaces • Consultees Appendix P – FNDP REG14 – Response table Appendix Q – Letter to owners of Angel Cottages – Proposed NDH 3 Consultation Statement July 2019 1. Introduction 1.1 The Fressingfield Neighbourhood Development Plan is a community--‐led document for guiding the future development of the parish. It is the first of its kind for Fressingfield and a part of the Government’s current approach to planning. It has been undertaken with extensive community engagement, consultation and communication. -

Notice of Poll and Situation of Polling Stations

NOTICE OF POLL AND SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS Suffolk County Council Election of a County Councillor for the Bosmere Division Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a County Councillor for Bosmere will be held on Thursday 4 May 2017, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of County Councillors to be elected is one. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Assentors CARTER Danescroft, Ipswich The Green Party Thomas W F Coomber Amy J L Coomber (++) Terence S Road, Needham (+) Ruth Coomber Market, Ipswich, Gregory D E Coomber Dorothy B Granville Suffolk, IP6 8EG Bistra C Carter Geoffrey M Turner Judith C Turner John E Matthissen Nicola B Gouldsmith ELLIOTT 3 Old Rectory Close, Labour Party William J Marsburg (+) Hayley J Marsburg (++) Tony Barham, IP6 0PY Brenda Smith William E Smith Gladys M Hiskey Clive I Hiskey Frances J Brace Kester T Hawkins Emma L Evans Paul J Marsburg PHILLIPS 46 Crowley Road, Liberal Democrat Wendy Marchant (+) Michael G Norris (++) Steve Needham Market, David J Poulson Graham T Berry IP6 8BJ Margaret A Phillips Lynn Gayle Anna L Salisbury Robert A Luff Peggy E Mayhew Peter Thorpe WHYBROW The Old Rectory, The Conservative Party Claire E Welham (+) Roger E Walker (++) Anne Elizabeth Jane Stowmarket Road, Candidate John M Stratton Carole J Stratton Ringshall, Stowmarket, Michael J Brega Claire V Walker Suffolk, IP14 2HZ Julia B Stephens-Row David E Stephens-Row Stuart J Groves David S Whybrow 4. -

Childcare Sufficiency Assessment (CSA) December 2019 – December 2020

Childcare Sufficiency Assessment (CSA) December 2019 – December 2020 Suffolk County Council Early Years and Childcare Service December 2019 Page 2 of 89 CONTENTS Table of Contents COVID – 19 5 1. Overall assessment and summary 5 England picture compared to Suffolk 6 Suffolk contextual information 6 Overall sufficiency in Suffolk 7 Deprivation 7 How Suffolk ranks across the different deprivation indices 8 2. Demand for childcare 14 Population of early years children 14 Population of school age children 14 3. Parent and carer consultation on childcare 15 4. Provision for children with special educational needs and disabilities 18 Number of children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) 18 5. Supply of childcare, Suffolk picture 20 Number of Early Years Providers 20 All Providers in Suffolk - LOP and Non LOP 20 Number of school age providers and places 21 6. Funded early education 22 Introduction to funded early education 22 Proportion of two year old children entitled to funded early education 22 Take up of funded early education 22 Comparison of take up of funded early education 2016 -2019 23 7. Three and four-year-old funded entitlement – 30hrs 24 30 hr codes used in Suffolk 25 Table 8 25 8. Providers offering funded early education places and places available. 26 Funded early education places available 26 Early education places at cluster level 28 9. Hourly rates 31 Hourly rate paid by Suffolk County Council 31 Hourly rate charged by providers 31 Mean hourly fee band for Suffolk 31 December 2019 Page 3 of 89 10. Quality of childcare 32 Ofsted inspection grades 32 11. -

Babergh District Council Work Completed Since April

WORK COMPLETED SINCE APRIL 2015 BABERGH DISTRICT COUNCIL Exchange Area Locality Served Total Postcodes Fibre Origin Suffolk Electoral SCC Councillor MP Premises Served Division Bildeston Chelsworth Rd Area, Bildeston 336 IP7 7 Ipswich Cosford Jenny Antill James Cartlidge Boxford Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 185 CO10 5 Sudbury Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Bures Church Area, Bures 349 CO8 5 Sudbury Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Clare Stoke Road Area 202 CO10 8 Haverhill Clare Mary Evans James Cartlidge Glemsford Cavendish 300 CO10 8 Sudbury Clare Mary Evans James Cartlidge Hadleigh Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 255 IP7 5 Ipswich Hadleigh Brian Riley James Cartlidge Hadleigh Brett Mill Area, Hadleigh 195 IP7 5 Ipswich Samford Gordon Jones James Cartlidge Hartest Lawshall 291 IP29 4 Bury St Edmunds Melford Richard Kemp James Cartlidge Hartest Hartest 148 IP29 4 Bury St Edmunds Melford Richard Kemp James Cartlidge Hintlesham Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 136 IP8 3 Ipswich Belstead Brook David Busby James Cartlidge Nayland High Road Area, Nayland 228 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Maple Way Area, Nayland 151 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Church St Area, Nayland Road 408 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Bear St Area, Nayland 201 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 271 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Shotley Shotley Gate 201 IP9 1 Ipswich -

Wills of Section 3

PREFACE. The following contents are transcriptions of the works and notes made by JAMES ARTHUR MINGAY (1855 - 1917) on the "History & Origins of the family name MINGAY". The original work is handwritten and was deposited in 1915 at the NORFOLK RECORD OFFICE under the reference number MS 4410 57X5. In transcribing this work every endeavour has been made to avoid errors but due to human frailty some may have created, if any have occurred, all due apologies are offered in advance. Also the transciber has made every effort to keep to the actual words & phrasing used by the Author, any doubt being indicated by the usual query mark. Some of the compilation is itself a transcription by persons usually honoured in the Preface of the main body of the work. The Original was generally written on one face of double Foolscap, hence whilst the originals' page numbering has been maintained only those pages on which notes were made have been recorded but not necessarily on on single pages due to the difference between the spacing of 'handwritten' and 'typewritten' letters/words. Within the original are many beautifully drawn (some in colour) Heraldary devices, which the transcriber has not be able to recreate in the same fashion. In order to broaden the interest, two more indexes have been added, viz:- Index of Beneficiaries & Witnesses and Index of Locations mentioned in the Wills of Section 3. A short biography of the Author of the original manuscript is as follows:- 'JAMES ARTHUR MINGAY was the sixth son of GEORGE WILLIAM MINGAY and his first wife CELIA neé ROPE being born on the 10th December 1855 at Valley Farm House, Middleton, Norfolk and baptised in North Runcton Church. -

Fressingfield 2008

conservation area appraisal © Crown copyright All rights reserved Mid Suffolk D C Licence no 100017810 2006 Introduction The conservation area in Fressingfield was originally designated by East Suffolk County Council in 1973, and inherited by Mid Suffolk District Council at its inception in 1974. The Council has a duty to review its conservation area designations from time to time, and this appraisal examines Fressingfield under a number of different headings as set out in English Heritage’s new ‘Guidance on Conservation Area Appraisals’ (2006). As such it is a straightforward appraisal of Fressingfield’s built environment in conservation terms and is essentially an update on a draft document produced back in 2000. This document is neither prescriptive nor overly descriptive, but more a demonstration of ‘quality of place’, sufficient for the briefing of the Planning Officer when assessing proposed works in the area. The photographs and maps are thus intended to contribute as much as the text itself. As the English Heritage guidelines point out, the appraisal is to be read as a general overview, rather than as a comprehensive listing, and the omission of any particular building, feature or space does not imply that it is of no interest in conservation terms. Text, photographs and map overlays by Patrick Taylor, Conservation Architect, Mid Suffolk District Council 2008. © Crown copyright All rights reserved Mid Suffolk D C Licence no 100017810 2006 Topographical Framework Fressingfield is a small village in north Suffolk. It is situated on the south- western bank of a tributary that runs three miles further north-westwards before joining the river Waveney, which here forms the boundary with Norfolk. -

All Notices Gazette

ALL NOTICES GAZETTE CONTAINING ALL NOTICES PUBLISHED ONLINE ON 25 JUNE 2014 PRINTED ON 26 JUNE 2014 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY | ESTABLISHED 1665 WWW.THEGAZETTE.CO.UK Contents State/2* Royal family/ Parliament & Assemblies/ Church/2* Companies/2* People/66* Money/ Environment & infrastructure/92* Health & medicine/ Other Notices/97* Terms & Conditions/98* * Containing all notices published online on 25 June 2014 STATE STATE COMPANIES Departments of State Corporate insolvency CROWN OFFICE NOTICES OF DIVIDENDS 2152057The Queen has been pleased by Letters Patent under the Great Seal 2152083In the Birmingham District Registry of the Realm dated 23 June 2014, to nominate the Reverend Canon No 6584 of 2013 John Bromilow Thomson, M.A., Ph.D., Director of Ministry in the ADVANTAGE TECHNOLOGY SERVICES LIMITED Diocese of Sheffield to be Bishop Suffragan of Selby and the 05963123 Venerable Paul John Ferguson, M.A., Archdeacon of Cleveland, to be Registered office: C/o Spearing Insolvency, 15 Highfield Road, Hall Bishop Suffragan of Whitby – both in the Diocese of York. Green, Birmingham B28 0EL C I P Denyer (2152057) Principal Trading Address: Eden House, Hartlebury Trading Estate, Hartlebury, Worcestershire DY10 4JB Notice is hereby given pursuant to Rule 11.2(1) of the Insolvency HONOURS & AWARDS Rules 1986, that I, Nigel Alexander Spearing, the Liquidator of the above-named Company, intend paying a First and Final dividend to 2152056BUCKINGHAM PALACE Creditors within two months of the last date for proving specified 25 June 2014 herein. Creditors who have not already proved are required on or THE QUEEN has been graciously pleased to give orders for the before 5 August 2014, to send in their names and addresses, with following Honorary appointments in Her Majesty’s Armed Forces:— particulars of their debts or claims, to the undersigned, Nigel Michael Cecil, Admiral the Lord BOYCE, KG, GCB, OBE, DL, as Alexander Spearing, of Spearing Insolvency, 15 Highfield Road, Hall Admiral of the Fleet. -

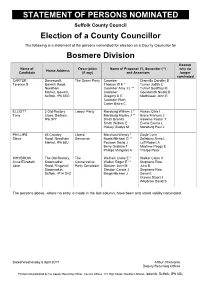

Statement of Persons Nominated

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED Suffolk County Council Election of a County Councillor The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a County Councillor for Bosmere Division Reason Name of Description Name of Proposer (*), Seconder (**) why no Home Address Candidate (if any) and Assentors longer nominated CARTER Danescroft, The Green Party Coomber Granville Dorothy B Terence S Ipswich Road, Thomas W F * Turner Judith C Needham Coomber Amy J L ** Turner Geoffrey M Market, Ipswich, Coomber Gouldsmith Nicola B Suffolk, IP6 8EG Gregory D E Matthissen John E Coomber Ruth Carter Bistra C ELLIOTT 3 Old Rectory Labour Party Marsburg William J * Hiskey Clive I Tony Close, Barham, Marsburg Hayley J ** Brace Frances J IP6 0PY Smith Brenda Hawkins Kester T Smith William E Evans Emma L Hiskey Gladys M Marsburg Paul J PHILLIPS 46 Crowley Liberal Marchant Wendy * Gayle Lynn Steve Road, Needham Democrat Norris Michael G ** Salisbury Anna L Market, IP6 8BJ Poulson David J Luff Robert A Berry Graham T Mayhew Peggy E Phillips Margaret A Thorpe Peter WHYBROW The Old Rectory, The Welham Claire E * Walker Claire V Anne Elizabeth Stowmarket Conservative Walker Roger E ** Stephens-Row Jane Road, Ringshall, Party Candidate Stratton John M Julia B Stowmarket, Stratton Carole J Stephens-Row Suffolk, IP14 2HZ Brega Michael J David E Groves Stuart J Whybrow David S The persons above, where no entry is made in the last column, have been and stand validly nominated. Dated Wednesday 5 April 2017 Arthur Charvonia Deputy Returning Officer Printed -

STATEMENT of PERSONS NOMINATED Election of a District

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED Mid Suffolk District Council Election of a District Councillor The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a District Councillor for Bacton Ward Reason why Name of Description Name of Proposer (*), Seconder (**) Home Address no longer Candidate (if any) and Assentors nominated* MELLEN 20 South View, Green Party Mellen Caleb * Stringer Sarah K Andy Westhorpe Road, Bean John H ** Stringer Andrew G Wyverstone, Chambers David Doherty Ann Stowmarket, IP14 John Doherty John 4SP Peacock Geoffrey Fearn Judy Mark Mellen Elizabeth H WILSHAW Guildhall Place, The Horn Glen * Flynn Keith Jill Rosemary The Street, Conservative Parnum Kate ** Jeffries Philip R Wyverstone, Party Candidate Bennett Sam Black A M Stowmarket, IP14 Bentley G Barker D E 4SJ Todd A I Bentley A M The persons above, where no entry is made in the last column, have been and stand validly nominated. Dated Thursday 4 April 2019 Arthur Charvonia Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Endeavour House, 8 Russell Road, Ipswich, Suffolk, IP1 2BX STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED Mid Suffolk District Council Election of a District Councillor The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a District Councillor for Battisford & Ringshall Ward Reason why Name of Description Name of Proposer (*), Seconder (**) Home Address no longer Candidate (if any) and Assentors nominated* OAKES 89 Stowmarket The Ford Nigel * Fellowes Thomas Kay Maxine Road, Needham Conservative Ford Marina ** Shilson Robert Market, Ipswich, Party Candidate Nunn Helen Phoenix James IP6 8ED Nunn Geoff Cochrane Rosemary Fellowes Rosamund Cochrane Shaun PRATT The Old Post Green Party Chapman P T * Sims P C Daniel Robert Office, Castle Chapman W A ** Bjornson F Road, Offton, Grimwood K E Bjornson A Ipswich, Suffolk, Finbow M Partridge S IP8 4RG Durrant S L Bjornson L C The persons above, where no entry is made in the last column, have been and stand validly nominated. -

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 DRIVERS JONAS and COMPANY {CHARTERED SURVEYORS}

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 DRIVERS JONAS AND COMPANY {CHARTERED SURVEYORS} LMA/4673 Reference Description Dates CORPORATE ARTICLES OF APPRENTICESHIP, CLERKSHIP AND PARTNERSHIP LMA/4673/A/01/001 Articles of Apprenticeship for five years as a 1832 Feb Land Surveyor Charles Burrell Driver and son Robert Collier Driver with James Marmont, Land Surveyor of Bristol. Robert Collier Driver is bound as apprentice to James Marmont. Copy 1 document Former Reference: DJ11 Envelope 4 LMA/4673/A/01/002 Articles of Clerkship 1860 May 2 Samuel Jonas and Henry Jonas with Charles Frederick Adams, Agent and Surveyor of Barkway, Hertfordshire. Henry Jonas is bound to Charles Frederick Adams for three years to practice as Land Agent and Surveyor. Signed 1 document Former Reference: DJ11 Envelope 7 LMA/4673/A/01/003 Articles of Partnership 1895 Between Charles William Driver, Henry Jonas and Robert Manning Driver. Unsigned draft 1 document of 7 pages Former Reference: DJ11 Envelope 10 LMA/4673/A/01/004 Deed of Apprenticeship 1895 Jan 30 Henry Jonas, Arthur Charles Driver and Charles William Driver. Arthur Charles Driver apprenticed to Henry Jonas for one year. Signed 1 document Former Reference: DJ11 Envelope 10 LMA/4673/A/01/005 Articles of Partnership 1905 - 1920 Between Henry Jonas, Robert Manning Driver, Arthur Charles Driver and Harold Driver Jonas (1905 Apr 27). Indenture added 1907 states that Robert Collier Jonas will become a partner. The retirement of Robert Manning Driver is noted as 31 Dec 1905. Memorandum added 22 June 1920 on retirement of Robert Collier Jonas and new proportions for profits and liabilities. -

Fressingfield | Suffolk | IP21 5PE

‘Village Life’ Fressingfield | Suffolk | IP21 5PE Step inside Set back from the road in the centre of the She had the french doors installed in order to sought after village of Fressingfield, this charming appreciate the beautiful views out over the semi-detached home is part of a converted courtyard and the churchyard beyond and to stable block and has a light and spacious living keep the room full of light. area and two good sized bedrooms with The doors open up directly onto the courtyard character features. The courtyard garden offers garden with its plentiful colourful planting and in a peaceful spot looking out over the village the summer months the free flow between churchyard. house and garden really brings the outside in. The decoration is neutral with light coloured • Charming Semi-Detached Village Home walls and carpets and the clever inbuilt storage • Great Lock Up and Go solution under the stairs makes excellent use of • Lovely Sitting Room the space available. The exposed brickwork • Spacious Kitchen Breakfast Room feature wall is a delightful historical feature that • Two Comfortable Bedrooms brings a unique style to the living area. • Study/Bedroom Three • Off Road Parking The kitchen/dining room has plenty of inbuilt • Pretty Courtyard Garden Overlooking storage and space for appliances. The room is Church Yard open plan with a spacious dining area and plenty • No Onward Chain of room for a dining table and seating. Making the Most of the Space Converted more than 30 years ago from a Upstairs there are two good sized bedrooms stable block that was used by the nearby pub, and a third room which is currently used as a The Swan, this property has provided easy and study. -

Alled the Iceni Or Cenomanni, Descended from the Cenomanni of Gaul

SUFFOL . THis is a maritime county, bounded on the north by Norfolk, from which it is separated by the Little Ouse and the Waveney livers; on the south by Essex, the liver Stour forming the divtsion; on the east by th~ German ocean, and on the west by Cambridgeshire. Its figure is an irregular oblong-from Aldborou~h, o~ the east, to Newmarket, on the borders of Cambridgeshire, on the west, about forty-seven miles ir. length; and from north to south the extent is about twenty-seven miles: its circumference has been estimated at one hundred and furty-four miles, and its area to comprise 1,512 square miles, or 967,680 statute acres. In size it ranks as the eleventh county in England, and in population as the seventeenth. NAME and ANCIENT HISTORY .-In the time of the Romans the inhabitants of this part of the country were called the Iceni or Cenomanni, descended from the Cenomanni of Gaul. Under the Roman dominion it was included in the province of Flama Cmsariensis. Under the Saxons it formed a part of the kingdom of East Anglia, and was designated Suffolk from Sud-folk literally 'southem folk' or 'people.' The whole of this and some of the adjacent counties experienced little respite from foreign and domestic depredators till !lome time after the death of Edward the Confessor: this county, in particular, suffered much from Sweyne, King of Denmark, who spared neither churches nor towns, unless redeemed by the people with lru·ge sums of money; though, to compensate in some measure for this cruelty, Canute, his son and successor, shewed it particular kindness.