Pdf/Estonia Code of Criminal Procedure.Pdf 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7 Political Corruption in Ukraine

NATIONAL SECURITY & DEFENCE π 7 (111) CONTENTS POLITICAL CORRUPTION IN UKRAINE: ACTORS, MANIFESTATIONS, 2009 PROBLEMS OF COUNTERING (Analytical Report) ................................................................................................... 2 Founded and published by: SECTION 1. POLITICAL CORRUPTION AS A PHENOMENON: APPROACHES TO DEFINITION ..................................................................3 SECTION 2. POLITICAL CORRUPTION IN UKRAINE: POTENTIAL ACTORS, AREAS, MANIFESTATIONS, TRENDS ...................................................................8 SECTION 3. FACTORS INFLUENCING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF COUNTERING UKRAINIAN CENTRE FOR ECONOMIC & POLITICAL STUDIES POLITICAL CORRUPTION ......................................................................33 NAMED AFTER OLEXANDER RAZUMKOV SECTION 4. CONCLUSIONS AND PROPOSALS ......................................................... 40 ANNEX 1 FOREIGN ASSESSMENTS OF THE POLITICAL CORRUPTION Director General Anatoliy Rachok LEVEL IN UKRAINE (INTERNATIONAL CORRUPTION RATINGS) ............43 Editor-in-Chief Yevhen Shulha ANNEX 2 POLITICAL CORRUPTION: SPECIFICITY, SCALE AND WAYS Layout and design Oleksandr Shaptala OF COUNTERING IN EXPERT ASSESSMENTS ......................................44 Technical & computer support Volodymyr Kekuh ANNEX 3 POLITICAL CORRUPTION: SCALE AND WAYS OF COUNTERING IN PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS AND ASSESSMENTS ...................................49 This magazine is registered with the State Committee ARTICLE of Ukraine for Information Policy, POLITICAL -

UKRAINE: Gongadze Convictions Are Selective Justice

UKRAINE: Gongadze convictions are selective justice Tuesday, March 25 2008 EVENT: The Gongadze file is not closed until the instigators of his murder have been held to account, Council of Europe rapporteur Sabine Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger said on March 19. SIGNIFICANCE: The three-year trial of three former policemen accused of killing journalist Georgii Gongadze has ended in jail terms of 12-13 years, but inside and outside Ukraine there have been calls for the investigation to move onto those behind the murder. One of the main factors why former supporters are so disillusioned with President Viktor Yushchenko -- who now has approval ratings of just 10% -- rests on his poor handling of the investigation of a murder that he promised as a matter of honour to resolve. ANALYSIS: The origins of the November-December 2004 wave of protests against election fraud that became known as the Orange Revolution lie in the 'Kuchmagate' crisis of four years earlier. In November 2000, Socialist Party leader Oleksandr Moroz, an opponent of President Leonid Kuchma while Moroz was parliamentary speaker in 1994-98, revealed to parliament tapes made in the president's office. They were part of hundreds of hours recorded by a Security Service (SBU) officer in the presidential guard, Mykola Melnychenko, in 1999-2000. Melnychenko was working for former SBU Chairman Yevhen Marchuk, who had a poor relationship with the then SBU head, Leonid Derkach. Marchuk accused Derkach and the SBU of involvement in Ukraine's illegal arms trade, and campaigned in the 1999 elections on an anti-Kuchma platform. The compromising intelligence on the tapes could have been used to force Kuchma to step down early and appoint a strongman, such as Marchuk, just as power was transferred in Russia from President Boris Yeltsin to Vladimir Putin in 1999-2000. -

Forcible Return/Torture, Lema Susarov

PUBLIC AI Index: EUR 50/007/2008 12 June 2008 Further Information on UA 207/07 (EUR 50/003/2007, 9 August 2007) and follow-ups (EUR 50/004/2007, 4 October 2007; EUR 50/004/2008, 7 March 2008) - Forcible return/torture UKRAINE Lema Susarov (m), ethnic Chechen The hearings of Lema Susarov's appeal against the Ukrainian authorities' rejection of his application for refugee status, and against the order to extradite him to the Russian federation, began on 9 and 10 June respectively. The prosecutor at the 10 June extradition hearing said that information on the risks Lema Susarov would face if sent to the Russian Federation (provided in a submission by AI Ukraine) was "not relevant," and that Lema Susarov could not be considered a refugee, because the Ukrainian authorities had rejected his application for refugee status. The next hearings will be on 23 June, with the extradition hearing in the morning and the refugee status hearing in the afternoon. The prosecutor also claimed on 10 June that Ukraine's obligations under the Minsk Convention (which governs judicial cooperation between members of the Commonwealth of Independent States) requires Ukraine to extradite those wanted by the requesting side, where there is reason to believe that they have committed grave crimes on the territory of the government making the request. This implies that the Minsk Convention overrides Ukraine's commitments under various UN treaties, notably the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment, which expressly prohibits the return of anyone to a country where they would be at risk of torture, as Lema Susarov would be if returned to the Russian Federation. -

Ukraine Page 1 of 32

Country Report on Human Rights Practices in Ukraine Page 1 of 32 Ukraine Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2007 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 11, 2008 Ukraine, which has a population of slightly less than 47 million, is a republic with a mixed presidential and parliamentary system, governed by a directly elected president and a unicameral Verkhovna Rada (parliament) that selects a prime minister. Preterm Verkhovna Rada elections were held on September 30. According to international observers, fundamental civil and political rights were respected during the campaign, enabling voters to freely express their opinions. Although the Party of Regions won a plurality of the vote, President Viktor Yushchenko's Our Ukraine-People's Self Defense Bloc and former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko's Bloc formed a coalition, and established a government with Tymoshenko as the prime minister. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control of the security forces. Problems with the police and the penal system remained some of the most serious human rights concerns. Problems included torture in pretrial detention facilities; harsh conditions in prisons and pretrial detention facilities; and arbitrary and lengthy pretrial detention. There was also continued violent hazing of military conscripts and government monitoring of private communications without judicial oversight. Slow restitution of religious property continued. There was societal violence against Jews and increased violence against persons of non-Slavic appearance. Anti-Semitic publications continued to be a problem. Serious corruption in all branches of government and the military services also continued. The judiciary lacked independence. Violence and discrimination against children and women, including domestic violence, sexual harassment in the workplace, and child labor, remained concerns. -

Constitutional Stage of the Judicial Reform in Ukraine

NATIONAL SECURITY & DEFENCE CONTENT π 2-3 (139-140) JUDICIAL REFORM IN UKRAINE: CURRENT RESULTS, PROSPECTS AND RISKS OF THE CONSTITUTIONAL STAGE 2013 (The Razumkov Centre’s Аnalytycal Report) ......................................................... 2 Founded and published by: 1. COURT WITHIN THE SYSTEM OF STATE GOVERNANCE: INTERNATIONAL NORMS AND STANDARDS .......................................................... 3 INTERNATIONAL NORMS ENSURING THE HUMAN RIGHT TO A FAIR TRIAL AS WELL AS THE INDEPENDENCE OF THE JUDICIARY AS AN IMPORTANT CONDITION FOR ITS IMPLEMENTATION (Annex) .................................................... 9 UKRAINIAN CENTRE FOR ECONOMIC & POLITICAL STUDIES 2. THE 2010 JUDICIAL REFORM: GOALS AND PROGRESS ...........................................15 NAMED AFTER OLEXANDER RAZUMKOV SEQUENCE OF EVENTS THAT PRECEDED THE JUDICIAL REFORM OF 2010 (Annex)... 29 Director General Anatoliy Rachok 3. SECOND (CONSTITUTIONAL) STAGE OF THE JUDICIAL REFORM: Editor Valeriya Klymenko PROSPECTS AND RISKS ..................................................................................... 35 Layout and design Oleksandr Shaptala 4. CONCLUSIONS AND PROPOSALS ........................................................................ 56 Technical support Volodymyr Kekukh EXPERT ASSESSMENTS THE JUDICIAL REFORM AND STATE OF THE JUDICIARY IN UKRAINE ......................... 62 This journal is registered with the State Committee NATIONWIDE SURVEY of Ukraine for Information Policy, COURTS AND JUDICIAL REFORM IN UKRAINE: PUBLIC OPINION .............................. -

RFERL Organised Crime

RADIO FREE EUROPE/RADIO LIBERTY, PRAGUE, CZECH REPUBLIC ________________________________________________________ RFE/RL Organized Crime and Terrorism Watch Vol. 3, No. 33, 19 September 2003 Reporting on Crime, Corruption, and Terrorism in the former USSR , Eastern Europe, and the Middle East END NOTE NEW EVIDENCE POINTS TO HIGH-LEVEL INVOLVEMENT IN POLITICAL MURDERS IN UKRAINE By Taras Kuzio Since the murder of opposition journalist Heorhiy Gongadze in fall 2000 the Ukrainian authorities have been incompetent in their handling of this case or have been unable to resolve it (or a mixture of the two). This is surprising because of the degree to which the Gongadze case has negatively affected both President Leonid Kuchma and Ukraine's domestic and international standing. From November 2000 to April 2002, one factor why the Gongadze case was not resolved was the role of then Prosecutor Mykhailo Potebenko, who shielded Kuchma from accusations that he was directly involved in the crime. Potebenko, his staf f, his successor Sviatoslav Piskun, as well as Ministry of Interior (MVS) chief Yuriy Smirnov have all arrived at contradictory and often bizarre explanations for Gongadze's murder. Yet, there are four facts that have been known for a long time which have been again authenticated by MVS sources. Firstly, it has now been admitted by the authorities that Gongadze was being followed prior to his death by the MVS. According to the 9-15 August edition of the respected weekly "Zerkalo nedeli" the documents pertaining to this were subsequently destroyed after the removal of MVS chief Yuriy Kravchenko in February 2001. Second, Kuchma was allegedly recorded by security guard Mykola Melnychenko as demanding that Gongadze be dealt with. -

Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych Introduces New Ukrainian Cabinet

INSIDE:• U.S. State Department releases human rights report — page 3. • Glaucoma center celebrates inaugural year in California — page 9. • Interview: Ukrainian scholars comment on Ukraine’s 15th anniversary — 11. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXXIV HE KRAINIANNo. 33 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, AUGUST 13, 2006 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine New government announces measures PrimeT Minister UViktor Yanukovych W to improve relations with Russia introduces new Ukrainian cabinet by Zenon Zawada by Zenon Zawada ing situations which emerged with Russia Kyiv Press Bureau Kyiv Press Bureau in the last year-and-a-half. We will exam- ine to what extent these things are well- KYIV – Prime Minister Viktor KYIV – Pro-Russian politicians took grounded and how much they impede our Yanukovych introduced his Cabinet of control of Ukraine’s key government relations in general,” he said. Ministers on August 4, just minutes after posts and announced measures to As his symbolic first foreign trip, Mr. the Verkhovna Rada affirmed his nomi- improve ties with the Russian Federation Yanukovych announced on August 10 nation. after the Verkhovna Rada voted August 4 that he will travel to Moscow between Of its 24 members, at least nine to affirm Viktor Yanukovych as August 15 and August 17 to visit Russian belong to the Party of the Regions, at Ukraine’s prime minister. Federation President Vladimir Putin. least five belong to the Our Ukraine fac- While Ukrainian President Viktor Mr. Putin called Mr. Yushchenko, and tion and two represent the Socialist Party Yushchenko has portrayed the new gov- then later Mr. -

Ukraine's Other War: the Rule of Law and Siloviky After the Euromaidan

The Journal of Slavic Military Studies ISSN: 1351-8046 (Print) 1556-3006 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fslv20 Ukraine’s Other War: The Rule of Law and Siloviky After the Euromaidan Revolution Taras Kuzio To cite this article: Taras Kuzio (2016) Ukraine’s Other War: The Rule of Law and Siloviky After the Euromaidan Revolution, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies, 29:4, 681-706, DOI: 10.1080/13518046.2016.1232556 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13518046.2016.1232556 Published online: 14 Oct 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 44 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=fslv20 Download by: [FU Berlin] Date: 04 November 2016, At: 12:07 JOURNAL OF SLAVIC MILITARY STUDIES 2016, VOL. 29, NO. 4, 681–706 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13518046.2016.1232556 Ukraine’s Other War: The Rule of Law and Siloviky After the Euromaidan Revolution Taras Kuzio University of Alberta ABSTRACT Ukraine underwent a second democratic revolution in 2013–2014, which led to the overthrow of President Viktor Yanukovych. The article analyzes the sources of the failure since the Euromaidan Revolution of Dignity to reform the rule of law, reduce high-level corruption, and apply justice to Yanukovych and his entourage for massive corruption that bankrupted Ukraine, murder of protestors, and treason. Introduction What the fuck are you doing? Getting ready, right. You are meeting with politicians, not with gangsters! Aren’t they the same thing, boss? (Drug trafficker Pablo Escobar talking to his henchmen1) The origins of Ukraine’s Revolution of Dignity, or what is more commonly known as the Euromaidan revolution,2 and how it culminated in repression, violence, and murder are well known.3 Pre-term elections, rather than removing President Viktor Yanukovych, were the goal of the revolution; his fleeing from Kyiv was unexpected. -

Enduring Crisis in Ukraine a Test Case for European Neighborhood Policy

Introduction Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Enduring Crisis in Ukraine A Test Case for European Neighborhood Policy Rainer Lindner SWP Comments As negotiations over an “enhanced agreement” begin between the European Union and Ukraine, the EU’s neighbor is again embroiled in a stubborn internal conflict over power and resources that will lead to early parliamentary elections and possibly to a premature presidential election too. Although the economy is stable and the country has good prospects of joining the WTO in fall 2007, Ukraine is currently politically paralyzed. The conservative left alliance of Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych and the quarreling democratic nationalist forces around President Viktor Yushchenko and former Prime Minister Yulia Timoshenko continue to face off irreconcilably. The Ukrainian parliament that was elected in free and fair elections just one year ago is on the point of being dissolved. The EU is regarded as a mediator, and it should adopt this role as part of its neighborhood policy. Three processes are currently under way elections of 2004 (presidency) and 2006 in Ukraine: Firstly, a two-party system is (parliament) in fact mirrors the state of the forming, with a left conservative party transformation process after fifteen years of labor and industry (Party of Regions, of independence. After making important Socialists, Communists) and a democratic steps toward democracy and the free nationalist camp (“Our Ukraine,” “Yulia market Ukraine is currently suffering a Timoshenko Bloc,” “Self-Defense Party,” constitutional and parliamentary crisis, “Forward Ukraine”); secondly, the power and foreign policy disorientation. struggle between president and prime minister is currently mushrooming into a broader conflict over power and resources Constitutional Crisis between the two camps of parties and The constitutional reform of early 2006 oligarchs; and thirdly, the left conservative shattered Ukraine’s already fragile political block is currently—at the beginning of equilibrium. -

Semi-Presidentialism and Inclusive Governance in Ukraine Reflections for Constitutional Reform Semi-Presidentialism and Inclusive Governance in Ukraine

Semi-presidentialism and Inclusive Governance in Ukraine Reflections for Constitutional Reform Semi-presidentialism and Inclusive Governance in Ukraine Reflections for Constitutional Reform Sujit Choudhry, Thomas Sedelius and Julia Kyrychenko © 2018 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance © 2018 Centre of Policy and Legal Reform International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. References to the names of countries and regions in this publication do not represent the official position of International IDEA regarding the legal status or policy of the entities mentioned. The electronic version of this publication is available under a Creative Commons Attribute- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) licence. You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the publication as well as to remix and adapt it, provided it is only for non-commercial purposes, that you appropriately attribute the publication, and that you distribute it under an identical licence. For more information visit the Creative Commons website: <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/>. International IDEA Strömsborg SE–103 34 Stockholm, Sweden Email: [email protected] Website: <http://www.idea.int> Centre of Policy and Legal Reform 4 Khreshchatyk St., of. 13 Kyiv, Ukraine, 01001 Email: [email protected] Website: <http://pravo.org.ua> Design and layout: International IDEA Cover image: Teteria Sonnna/Flickr (CC BY 2.0) ISBN: 978-91-7671-154-5 Created with Booktype: <https://www.booktype.pro> International IDEA | Centre of Policy and Legal Reform Contents About this report ....................................................................................................... -

For Free Distribution

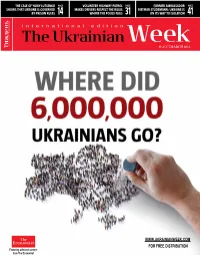

THE CASE OF YURIY LUTSENKO PAGE VOLUNTEER HIGHWAY PATROL PAGE FORMER AMBASSADOR PAGE SHOWS THAT UKRAINE IS GOVERNED MAKES DRIVERS RESPECT THE RULES DIETMAR STÜDEMANN: UKRAINE IS BY PRISON RULES 14 WHERE THE POLICE FAILS 31 ON ITS WAY TO ISOLATION 41 № 4 (27) MARCH 2012 WWW.UKRAINIANWEEK.COM FOR FREE DISTRIBUTION Featuring selected content from The Economist |CONTENTS BRIEFING FOCUS Carte Blanche Where did We Were Iryna Kurylo for the Empire: 6 million talks about A guideline Ukrainians Ukraine’s key to winning a disappear demographic presidential election to? problems and in Russia from 52 what causes Mr. Putin 4 6 them 8 Million POLITICS Demographics The Nation Concrete Justice: Paradoxes: Why Needs Ukraine is governed Western Ukraine Astronauts: by prison rules is in a far better Let’s make position than love! eastern oblasts 10 12 14 NEIGHBOURS Elite-less: A Trade and Demographic New appointments Donor for Russia? Russia’s in the government are more accession to the WTO signals like window-dressing than a renewed effort to draw an overhaul of the elite Ukraine into a Eurasian union 18 24 ECONOMICS SOCIETY Ready, Set, Go! Ukraine Too Many Cars, Too I Park Like an Idiot: is experiencing an Few Buyers: Luxury Volunteer highway automotive boom cars are speeding patrol make drivers even as the world car ahead; lesser respect the rules industry struggles brands are stalled where the police 26 28 fails 31 HISTORY Church Opposition: Privatization Targets Unknown Eastern Metropolitan Sofroniy Culture: The party Ukraine: What Dmytruk talks about -

Ukraine Page 1 of 44

2008 Human Rights Reports: Ukraine Page 1 of 44 2008 Human Rights Reports: Ukraine BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR 2008 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices February 25, 2009 Ukraine, population 46 million, is a republic with a mixed presidential and parliamentary system, governed by a directly elected president and a unicameral parliament (the Verkhovna Rada) that selects a prime minister. Parliamentary elections were held in September 2007; according to international observers, fundamental civil and political rights were respected during the campaign, enabling voters to express their opinions freely. Five political parties and blocs held seats in the 450 member parliament. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control of the security forces. The police and penal systems continued to be sources of some of the most serious human rights concerns. They included instances of torture by law enforcement personnel, harsh conditions in prisons and detention facilities, and arbitrary and lengthy pretrial detention. The judiciary lacked independence and suffered from corruption. The government continued to be slow to return religious property. Societal violence against Jews continued to be a problem, as did anti Semitic publications, although their number and circulation declined during the year. Serious corruption persisted in all branches of the government. Societal problems included violence and discrimination against women, including domestic violence and sexual harassment in the workplace, and against children, as well as increased violence against persons of non Slavic appearance. Discrimination against Roma continued. Trafficking in persons continued to be a serious problem. Workers continued to face limitations on their ability to form and join unions of their choice and to bargain collectively.