Interview - by Victor L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

Mayodan High School Yearbook, "The Anchor"

» :-.i.jV Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/anchor1958mayo ^he eAncko ,,: ^ . 1958 CHARLOTTE GANN - Editor-in-Chief SHIRLEY EASTER Assistant Editor MILDRED WHITE Sales Manager BETTY S. WILKINS Advertising MONTSIE ALLRED Class Editor FRANKIE CARLTON Picture Editor ROGER TAYLOR Art Editor UDELL WESTON Sports Editor JIMMY GROGAN Feature Editor foreword The Senior Class of '58 presents this ANCHOR as a token of our appreciation to all who have helped us progress through the past years, especially our parents, teach- ers, fellow students, and Mr. Duncan. success, It is our sincere hope that your lives may be filled with happiness and and that you will continue to manifest a spirit of loyalty to Mayodan High School. SHIRLEY EASTER CHARLOTTE GANN ^Dedication To our parents, who, in the process of rearing us, have picked us up when we have fallen, pushed us when we needed pushing, and have tried to understand o u r problems when on one else would listen to us! Because of their faithfulness, understanding, and undying love, for which we feel so deeply grateful, we dedicate to them our annual, the ANCHOR of 1958. The Seniors ^iicfk Oc/tocl faculty Not Pictured HATTIE RUTH HYDER ELLIOTT F. DUNCAN VIOLET B. SULEY B. S., A. S. T. C. A. B., U. N. C. A. B., Wisconsin University Home Economics Principal Biology Not Pictured OTIS J. STULTZ IRMA S. CREWS HENRY C. M. WHITAKER B. A., Elon College B. A., Winthrop College A. B., High Point College Business Administration A. B., High Point College Spanish, Social Studies, Band Mathematics, English MAUD G. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER , President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 4, 2016, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters GARY BURTON WENDY OXENHORN PHAROAH SANDERS ARCHIE SHEPP Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center’s Artistic Director for Jazz. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 2 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, pianist and Kennedy Center artistic director for jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, chairman of the NEA DEBORAH F. RUTTER, president of the Kennedy Center THE 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS Performances by NEA JAZZ MASTERS: CHICK COREA, piano JIMMY HEATH, saxophone RANDY WESTON, piano SPECIAL GUESTS AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE, trumpeter LAKECIA BENJAMIN, saxophonist BILLY HARPER, saxophonist STEFON HARRIS, vibraphonist JUSTIN KAUFLIN, pianist RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA, saxophonist PEDRITO MARTINEZ, percussionist JASON MORAN, pianist DAVID MURRAY, saxophonist LINDA OH, bassist KARRIEM RIGGINS, drummer and DJ ROSWELL RUDD, trombonist CATHERINE RUSSELL, vocalist 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS -

Johnny O'neal

OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BOBDOROUGH from bebop to schoolhouse VOCALS ISSUE JOHNNY JEN RUTH BETTY O’NEAL SHYU PRICE ROCHÉ Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East OCTOBER 2017—ISSUE 186 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JOHNNY O’NEAL 6 by alex henderson [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JEN SHYU 7 by suzanne lorge General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : BOB DOROUGH 8 by marilyn lester Advertising: [email protected] Encore : ruth price by andy vélez Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : betty rochÉ 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : southport by alex henderson US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Fred Bouchard, Festival Report Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, 13 Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, special feature 14 by andrey henkin Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, CD ReviewS 16 Suzanne Lorge, Mark Keresman, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, Miscellany 41 John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Event Calendar Contributing Writers 42 Brian Charette, Ori Dagan, George Kanzler, Jim Motavalli “Think before you speak.” It’s something we teach to our children early on, a most basic lesson for living in a society. -

The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBoRAh F. RUTTER, President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 16, 2018, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2018 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters TODD BARKAN JOANNE BRACKEEN PAT METHENY DIANNE REEVES Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz. This performance will be livestreamed online, and will be broadcast on Sirius XM Satellite Radio and WPFW 89.3 FM. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 10:33 AM Page 2 THE 2018 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, Kennedy Center Artistic Director for Jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, Chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts DEBORAH F. RUTTER, President of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts The 2018 NEA JAzz MASTERS Performances by NEA Jazz Master Eddie Palmieri and the Eddie Palmieri Sextet John Benitez Camilo Molina-Gaetán Jonathan Powell Ivan Renta Vicente “Little Johnny” Rivero Terri Lyne Carrington Nir Felder Sullivan Fortner James Francies Pasquale Grasso Gilad Hekselman Angélique Kidjo Christian McBride Camila Meza Cécile McLorin Salvant Antonio Sanchez Helen Sung Dan Wilson 4-16 JAZZ NEA Jazz.qxp_WPAS 4/6/18 -

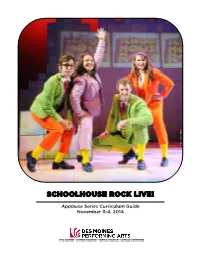

Schoolhouse Rock Live!

Tim Trumble Photo Photo Trumble Tim SCHOOLHOUSE ROCK LIVE! Applause Series Curriculum Guide November 3-4, 2014 Dear Teachers, Thank you for joining us for the Applause Series presentation of GUIDE CONTENTS Schoolhouse Rock Live! We are thrilled to present this popular Childsplay production for the first time in Des Moines. This high-energy show, packed with catchy, memorable songs, may About Des Moines have you remembering your childhood and watching the original Performing Arts Schoolhouse Rock cartoons that aired on Saturday mornings. Page 3 This time, these songs explode onto the stage for a whole new generation, creating excitement for a variety of academic Going to the Theater and subjects. Theater Etiquette Page 4 We thank you for sharing this very special experience Civic Center Field Trip with your students and Information for Teachers hope this study guide Page 5 helps to connect the performance to your Vocabulary in-classroom Pages 6-7 curriculum in ways that you find valuable. In the About the Performance following pages, you will Pages 8-9 find contextual information about the performance and About Childsplay and the related subjects, as well as a variety of discussion Creative Team questions and assessment activities. Some pages are Page 10 appropriate to reproduce for your students; others are designed more specifically with you, their teacher, in mind. As such, we About Schoolhouse Rock hope that you are able to “pick and choose” material and ideas Page 11 from the study guide to meet your class’s unique needs. Pre-Show -

Saxophone Colossus”—Sonny Rollins (1956) Added to the National Registry: 2016 Essay by Hugh Wyatt (Guest Essay)*

“Saxophone Colossus”—Sonny Rollins (1956) Added to the National Registry: 2016 Essay by Hugh Wyatt (guest essay)* Album cover Original album Rollins, c. 1956 The moniker “Saxophone Colossus” aptly describes the magnitude of the man and his music. Walter Theodore Rollins is better known worldwide as the jazz giant Sonny Rollins, but in addition to Saxophone Colossus, he has also been given other nicknames, most notably “Newk” because of his resemblance to baseball legend Don Newcombe. To use a cliché, Saxophone Colossus best describes Sonny because he is bigger than life. He is an African American of mammoth importance not only because he is the last major remaining jazz trailblazer, but also because he helped to inspire millions of fans and others to explore the religions and cultures of the East. A former heroin addict, the tenor saxophone icon proved that it was possible to kick the drug habit at a time in the 1950s when thousands of fellow musicians abused heroin and other narcotics. His success is testimony to his strength of character and powerful spirituality, the latter of which helped him overcome what musicians called “the stick” (heroin). Sonny may be the most popular jazz pioneer who is still alive after nearly seven decades of playing bebop, hard bop, and other styles of jazz with the likes of other stalwart trailblazers such as Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Clifford Brown, Max Roach, and Miles Davis. He follows a tradition begun by Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Charlie Parker. Eight months after overcoming his habit at a drug rehabilitation facility called “the farm” in Lexington, Kentucky, Sonny made what the jazz cognoscenti rightly contend is his greatest recording ever—ironically entitled “Saxophone Colossus”—which was recorded on June 22, 1956. -

Media Contact: Casey Blake 480-644-6620 [email protected] Ali Jackson Trio Performing Live at Mesa Arts Center

Media Contact: Casey Blake 480-644-6620 [email protected] Ali Jackson Trio Performing Live at Mesa Arts Center Saturday, Oct. 18 For immediate release: Sept. 17, 2014 Mesa, AZ – World renowned jazz drummer and member of the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, Ali Jackson, and two other talented jazz musicians, forming the Ali Jackson Trio, will be performing at Mesa Arts Center’s Piper Repertory Theater on Oct. 18 at 7:30 p.m. Tickets are available at mesaartscenter.com or by calling 480-644-6500. Ali Jackson is a world renowned modernist jazz drummer. He takes the principle of drumming and creates an irresistible beat. Jackson’s skill and concentration is unmatched, creating distinct rhythms and using abstract methods in a classic style. Currently, he is the principle drummer in the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis and is in his 7th season. Growing up in New York City and Detroit in an open music environment, Jackson took in all that he could from music. By the age of 8, he was playing on the streets of Detroit with his father, famed bassist Ali Jackson Sr. and getting insight on his talents from Donald Byrd, Betty Carter and Aretha Franklin. As a strong advocate for arts education, he has given numerous lectures at schools, such as New York University, Stanford University, Eastman College of Music, Columbia University, and West Virginia University, just to name a few. Jackson’s passion for musical outreach is incredible, touring continents and teaching others about the power of music. Jackson is currently touring with Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra in Western Europe. -

On Her New Album, Jazzmeia Horn Wants to Embolden Listeners to “Do Something About It”

On Her New Album, Jazzmeia Horn Wants to Embolden Listeners to “Do Something About It” The Dallas native’s jazz statement ’Love and Liberation’ is a call to action. BY TAYLOR CRUMPTON DATE AUG 28, 2019 SHARE NOTES 0 COMMENTS Emmanuel Afolabi azzmeia Horn’s preternatural musical talents emerged early on in her hometown of Dallas, first in her grandfather’s Southern Baptist choir and later at Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts. Horn, 28, has since J grown into one of contemporary jazz’s young icons, thanks to her inimitable vocal approach and command of generational techniques. After graduating from The New School’s renowned Jazz and Contemporary Music program, Horn delved into New York City’s jazz scene, performing at the likes of the Apollo. In 2015, she won the Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition, the genre’s elite tournament aimed at finding the next generation of jazz experts. Two years later, she released her debut album, A Social Call, which earned her a Grammy nomination. Horn released her second album, Love and Liberation, on Friday. It’s a meld of original compositions rooted in community and lived experiences. The standout cover “Green Eyes” is an ode to her fellow Dallas sister Erykah Badu, and “No More” is Horn’s testimonial about embracing her beauty as a Black woman. “I remember every time I would walk out of my house in Texas when I was a little girl to catch the bus to school, and my mom or grandmother would have to walk me to the bus stop to make sure the white children didn’t pick on me,” she’s said of the song. -

Full Biography

FULL BIO For forty years, pianist/composer and Fulbright Scholar ARMEN DONELIAN has distinguished himself in 25 countries as a performer, recording artist, master class leader and with his published writings. Donelian’s music is a distinctive blend of 20 influences including his Armenian origin, his Classical technique, and his association with some of the biggest names in Jazz. And, according to Metronom Magazine (1986), he achieves this fusion In such a natural way that one can tell it’s a master’s work. “The best time to learn music,” says Davis and John Coltrane. “Folk, Rock, Dixieland, Jazz, Church, Show and Society music – I played pianist Armen Donelian, “is when you’re them all while growing up,” says Donelian. young, while the brain synapses are still open and fresh. I started playing by ear “In college, I made money by accompanying when I was 5 or 6, and started classical theater and dance classes, providing cocktail music piano lessons when I was about 7 at the at a restaurant on campus and playing and Westchester Conservatory of Music. I arranging for an 8-piece Jazz/Rock band. After was lucky to have parents who supported graduation, I had no gigs, no direction, and lived at my musical aspiration.” home for a few months. My ex-girlfriend’s mother told me, ‘Armen, nothing is going to happen unless As a child, Armen absorbed the sound of you make it happen.’ Armenian, Turkish, Greek and Middle Eastern music at social gatherings and “So, after graduating from Columbia University in from records his father played at home. -

View 2012 Program

INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR IMPROVISED MUSIC SIXTH FESTIVAL/CONFERENCE Improvisation · Self · Community·World February 16-19, 2012 William Paterson University Wayne, New Jersey, USA Keynote artists and performers: Pyeng Threadgill & trio Ikue Mori, Sylvie Courvoisier & Jim Black Mulgrew Miller WyldLyfe Robert Dick & Tom Buckner Karl Berger with the University of Michigan Creative Arts Orchestra And over 50 other artists presenting concerts, panels, talks and workshops! ISIM President’s Welcome ISIM President’s Welcome On behalf of the Board of Directors of the International Society for Improvised Music, I extend to all of you a hearty welcome to the sixth ISIM Festival/Conference. Nothing is more gratifying than gatherings of improvising musicians as our common process, regardless of surface differences in our creative expressions, unites us in ways that are truly unique. As the conference theme suggests, by going deep within our reservoir of creativity, we access subtle dimensions of self—or consciousness—that are the source of connections with not only our immediate communities but the world at large. It is dificult to imagine a moment in history when the need for this improvisation-driven, creativity revolution is greater on individual and collective scales than the present. Please join me in thanking the many individuals, far too many to list, who have been instrumental in making this event happen. Headliners Ikue Mori, Pyeng Threadgill, Wyldlife, Karl Berger, the University of Michigan Creative Arts Orchestra, the William Paterson University jazz group, Mulgrew Miller, Robert Dick, and Thomas Buckner—we could not have asked for a more varied and exciting line-up. ISIM Board members Stephen Nachmanovitch and Bill Johnson have provided invaluable assistance, with Steve working his usual heroics with the ISIM website in between, and sometimes during, his performing and speaking tours.