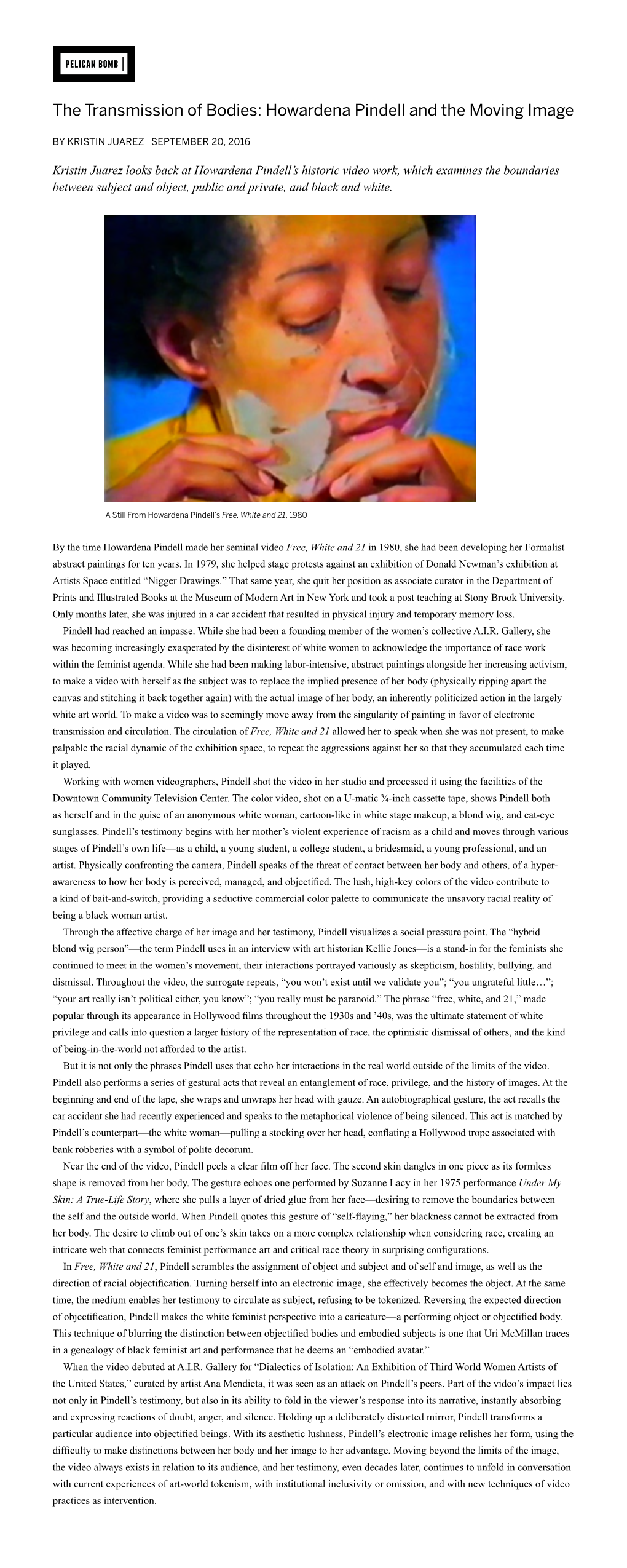

Howardena Pindell and the Moving Image

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with Howardena Pindell, 2012 Dec. 1-4

Oral history interview with Howardena Pindell, 2012 Dec. 1-4 Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a recorded interview with Howardena Pindell on December 1, 2012. The interview took place at the home of Howardena Pindell in New York City, and was conducted by Judith O. Richards for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Howardena Pindell has reviewed the transcript. Her corrections and emendations appear below in brackets with initials. This transcript has been lightly edited for readability by the Archives of American Art. The reader should bear in mind that they are reading a transcript of spoken, rather than written, prose. Interview JUDITH RICHARDS: This is Judith Richards, interviewing Howardena Pindell on December 1, 2012, at her home in New York City on Riverside Drive, for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, disk one. Howardena, as we've discussed, we're going to begin where a previous interview for the archives left off. That interview was on July 10, 1972. [Laughs.] So casting way back to 1972, I wanted to, first of all, ask some basic questions. HOWARDENA PINDELL: Mm-hmm [Affirmative.] JUDITH RICHARDS: Where were you living in 1972? Had you moved into Westbeth by then? HOWARDENA PINDELL: All right— JUDITH RICHARDS: Or were you living in— HOWARDENA PINDELL: —I was in Westbeth. JUDITH RICHARDS: And when did you move in there? Were you one of the first tenants? HOWARDENA PINDELL: One of the first tenants, yes. -

Feminist Artists' Book Projects of the 1980-90S

1 Bookworks as Networks: Feminist Artists’ Book Projects of the 1980-90s Caroline Fazzini Recent trends in contemporary exhibition, academic, and artistic practices in the U.S. illuminate a persistent concentration of efforts to present more complete versions of the past, specifically regarding issues of diversity and representation. Some museums and art historians have responded to the call for inclusivity by supporting exhibitions that focus on artists who have been marginalized. We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-1985, and Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985, which opened in 2017 at the Brooklyn Museum and the Hammer Museum, respectively, exemplify this corresponding surge of interest within the art and academic worlds of the Americas regarding women artists, and particularly women artists of color. My studies of these exhibitions, as well as my interest in artists’ books, led me to identify two collaborative artists’ book projects that emerged in the late 1980s, in the immediate aftermath of the time periods addressed in both We Wanted a Revolution and Radical Women. I aim to contribute to revisionist scholarly efforts by examining these two projects: Coast to Coast: A Women of Color National Artists’ Book Project (1987-1990) and Connections project/Conexus (1986-1989). Both were first and foremost, meant to initiate dialogues and relationships between women across borders through the making of art and artists’ books. While neither project has received scholarly attention to date, they are important examples of feminist collaborations between women artists. The projects, Connections project/Conexus (1986-1989), organized by Josely Carvalho and Sabra Moore, and Coast to Coast: A Women of Color National Artists’ Book Project (1987- 90), organized by Faith Ringgold and Clarissa Sligh, both took advantage of the accessibility of 2 artists’ books in an effort to include and encourage the participation of women artists. -

Digital Review Copy May Not Be Copied Or Reproduced Without Permission from the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago

DIGITAL REVIEW COPY MAY NOT BE COPIED OR REPRODUCED WITHOUT PERMISSION FROM THE MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART CHICAGO. HOWARDENA PINDELL WHAT REMAINS TO BE SEEN Published by the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago and DelMonico Books•Prestel NAOMI BECKWITH is Marilyn and Larry Fields Curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. VALERIE CASSEL OLIVER is Sydney and Frances Lewis Family Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. ON THE JACKET Front: Untitled #4D (detail), 2009. Mixed media on paper collage; 7 × 10 in. Back: Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, Howardena Pindell from the series Art World, 1980. Gelatin silver print, edition 2/2; 13 3/4 × 10 3/8 in. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Neil E. Kelley, 2006.867. © Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, All Rights Reserved. Courtesy of Hiram Butler Gallery. Printed in China HOWARDENA PINDELL WHAT REMAINS TO BE SEEN Edited by Naomi Beckwith and Valerie Cassel Oliver Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago DelMonico Books • Prestel Munich London New York CONTENTS 15 DIRECTOR’S FOREWORD Madeleine Grynsztejn 17 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Naomi Beckwith Valerie Cassel Oliver 21 OPENING THOUGHTS Naomi Beckwith Valerie Cassel Oliver 31 CLEARLY SEEN: A CHRONOLOGY Sarah Cowan 53 SYNTHESIS AND INTEGRATION IN THE WORK Lowery Stokes Sims OF HOWARDENA PINDELL, 1972–1992: A (RE) CONSIDERATION 87 BODY OPTICS, OR HOWARDENA PINDELL’S Naomi Beckwith WAYS OF SEEING 109 THE TAO OF ABSTRACTION: Valerie Cassel Oliver PINDELL’S MEDITATIONS ON DRAWING 137 HOWARDENA PINDELL: Charles -

Howardena Pindell

HOWARDENA PINDELL Born in 1943 in Philadelphia, USA Lives and works in New York, USA Education 1965-67 Yale University, New Haven, USA 1961-65 Boston University, Boston, USA Solo Exhibitions 2019 What Remains To Be Seen, Rose Art Museum Waltham, Massachusetts, USA 2018 Howardena Pindell, Document Gallery, Chicago, USA Howardena Pindell: What Remains to Be Seen, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond; Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts (2018-2019), USA 2017 Howardena Pindell: Recent Paintings, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York, USA 2015 Howardena Pindell, Honor Fraser, Los Angeles, USA Howardena Pindell, Spelman College Museum of Fine Art, Atlanta, USA 2014 Howardena Pindell: Paintings, 1974-1980, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York, USA 2013 Howardena Pindell: Video Drawings, 1973-2007, Howard Yezerski Gallery, Boston, USA 2009 Howardena Pindell: Autobiography: Strips, Dots, and Video, 1974-2009, Sandler Hudson Gallery, Atlanta, USA 2007 Howardena Pindell: Hidden Histories, Louisiana Art and Science Museum, Baton Rouge, USA 2006 Howardena Pindell: In My Lifetime, G.R. N’Namdi Gallery, New York, USA 2004 Howardena Pindell: Works on Paper, 1968-2004, Sragow Gallery, New York, USA Howardena Pindell: Visual Affinities, Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, NY, USA 2003 Howardena Pindell, G.R. N’Namdi Gallery, Detroit, USA 2002 Howardena Pindell, Diggs Gallery, Winston-Salem State University, North Carolina, USA 2001 Howardena Pindell: An Intimate Retrospective, Harriet Tubman Museum, Macon, Georgia, USA 2000 Howardena Pindell: Collages, G.R. N’Namdi Gallery, Birmingham, Michigan, USA Howardena Pindell: Recent Work, G.R. N’Namdi Gallery, Chicago, USA 1999 Witness to Our Time: A Decade of Work by Howardena Pindell, The Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, NY, USA 1996 Howardena Pindell: Mixed Media on Canvas, Johnson Gallery, Bethel University, St. -

Howardena Pindell: What Remains to Be Seen, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, No

ISSN: 2471-6839 Cite this article: Andrea Douglas, review of Howardena Pindell: What Remains to Be Seen, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 4, no. 2 (Fall 2018), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.1677. Howardena Pindell: What Remains To Be Seen Curated by: Naomi Beckwith and Valerie Cassel Oliver Exhibition schedule: Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, February 24–May 20, 2018; Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, August 25–November 25, 2018; and Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA, January 24–June 16, 2019 Exhibition catalogue: Naomi Beckwith and Valerie Cassel Oliver, Howardena Pindell: What Remains To Be Seen, exh. cat. Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago in association with Delmonico Books, Prestel, 2018. 288 pp.; 250 color illus. Hardcover $60.00 (ISBN: 9783791357379) Reviewed by: Andrea Douglas, Executive Director, Jefferson School African American Heritage Center; Researcher McIntire Department of Art, University of Virginia Fig. 1. Howardena Pindell, Autobiography: Air (CS560), 1988 (left). Acrylic, tempera, oil stick, blood, paper, polymer, photo transfer and vinyl on canvas, 86 x 84 in. Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society Purchase, W. Hawkins Ferry Fund with funds from Joan and Armando Ortiz Foundation, Friends of Modern Art, Avery K. Williams, Lynne Enweave, Ronald Maurice Ollie, and Kimberly Moore It is not faint praise to describe the fifty-year retrospective exhibition of multimedia artist Howardena Pindell as wholly satisfying. What has until now seemed an incomplete journalpanorama.org • [email protected] • ahaaonline.org Douglas, review of Howardena Pindell Page 2 assessment of the artist’s standing within the development of contemporary art has been synthesized into a presentation that neither privileges her role as artist activist nor her formalist experimentation but reveals the inextricable relationship between the artist’s biography and her studio practice. -

Biographical Description for the Historymakers® Video Oral History with Howardena Pindell

Biographical Description for The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History with Howardena Pindell PERSON Pindell, Howardena, 1943- Alternative Names: Howardena Pindell; Life Dates: April 14, 1943- Place of Birth: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA Residence: New York, NY Work: Stonybrook, NY Occupations: Collage Artist; Curator; Art Professor Biographical Note World renowned abstract artist Howardena Pindell was born on April 14, 1943, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Pindell became interested in art at an early age when she began taking art classes on Saturdays; she started out as a figurative painter. Pindell received her B.F.A. degree in painting from Boston University's School of Fine and Applied Arts in 1965, and her M.F.A. degree from Yale University's School of Art and Architecture in 1967. Pindell was also awarded two honorary in 1967. Pindell was also awarded two honorary doctorates: one from the Massachusetts College of Art, and one from Parson School of Design in New York. Pindell began her career in the art world as the first African American Associate Curator of Prints and Illustrated Books at the New York Museum of Modern Art, a position she held for twelve years. Pindell rose from Curatorial Assistant to Associate Curator during her time at the New York Museum of Modern Art.. In 1979, Pindell began a new career as Associate Professor of Students at State University of New York at Stony Brook. Pindell’s earliest drawings, composed of a patterned sequence of words and numbers on graph paper, suggest post minimalism as a major ingredient in her abstractions. In the 1970s, Pindell developed a collage technique using small circles hand punched from sheets of blank or printed paper. -

Howardena Pindell: Early Paintings

Garth Greenan Gallery 545 West 20th Street New York NY 10011 212 929 1351 www.garthgreenan.com Howardena Pindell: Early Paintings For the 2016 edition of Art Basel: Miami Beach, Survey, Garth Greenan Gallery presents a solo-exhibition of works by Howardena Pindell. The works included—three monumental paintings—provide an overview of the artist’s work from 1971–1973, an incredibly innovative and unique period for the artist. Among Pindell’s first forays into abstraction, on unprimed canvas, these works have the appearance of vast fields from which light emanates. They also convey the impression of pigment having been beaten into the surface rather than simply applied with a brush. In this, they recall the effect of African cloth made from pounded fiber and natural dyes. The relative darkness of her work at this time may be attributed to the fact that she painted mostly at night; her Untitled, 1972 days were spent working in various curatorial departments at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Increasingly, she favored the handmade, process-oriented, even craft- intensive approach to art that has proved her natural bent. Only one of the paintings – Untitled (1971) – has ever before been exhibited. The year that it was painted it appeared in Robert M. Doty’s landmark exhibition Contemporary Black Artists in America at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Untitled (1973) is the first painting onto which Pindell added her signature: hand- punched paper circles. Born in Philadelphia in 1943, Howardena Pindell studied painting at Boston University and Yale University. After graduating, she accepted a job in the Department of Prints and Illustrated Books at the Museum of Modern Art, where she remained for 12 years (1967–1979). -

Feminist Studies > Reclaiming Histories: Betye and Alison Saar, Feminism, and the Representation of Black Womanhood

Reclaiming Histories: Betye and Alison Saar, Feminism, and the Representation of Black Womanhood Jessica Dallow The feminist movement has given me more professional exposure. But I resist that now, just like I resist exhibiting in African Amer- ican artists' shows. I've always worked the same way, and haven't done anything I would consider "feminist art." –Betye Saar Yes, I am a feminist. I was involved with the Women's Space [Womanspace] here in Los Angeles. Feminism for me implies more like humanism, just accepting yourself and knowing that it's okay to be the way you are. For me the ultimate goal is to be a whole person and to accept the outcome. –Betye Saar People aren't really ready to deal with fierce female passion. –Alison Saar Betye Saar considers herself a feminist; however she resists designating her artwork as such. Similarly, Alison Saar, Betye's daughter, avoids labeling her own art as feminist.1 Yet, both artists have helped to shape a feminist consciousness in the arts since the early 1970s through their probing constructions of autobiography, self-identity, family, and the fe- male body: a consciousness circulating around the historical develop- ment of the African American female nude. Betye's early ideas of spiritu- ality and ethnicity, shaped in the early 1970s, have germinated within her daughter, evidenced by Alison's bust- and full-length nude, non- white female figures of the 1980s and 1990s. The Saars' intergenera- tional explorations of race, history, and the black female body represent a crucial step to reclaim the contentious history surrounding the visual representation of African American women. -

Painting While Black: Exploring Racial Identity Through Iconography

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2021 Painting While Black: Exploring Racial Identity Through Iconography Blake Morton Blake Morton Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses Part of the Painting Commons Recommended Citation Morton, Blake and Morton, Blake, "Painting While Black: Exploring Racial Identity Through Iconography" (2021). CMC Senior Theses. 2521. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/2521 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAINTING WHILE BLACK: EXPLORING RACIAL IDENTITY THROUGH ICONOGRAPHY By BLAKE DEREK MORTON SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR KASPER KOVITZ PROFESSOR TIA BLASSINGAME DECEMBER 4th, 2020 Morton 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 2 Introduction 3 Section 1 4 1. Historical Background 4 2. Post-Black Art 5 Section 2 6 1. Glenn Ligon 6 2. Kerry James Marshall 7 3. Kara Walker 8 Section 3 9 1. Production 9 2. Execution 10 3. Reflection 12 4. Bibliography 13 Morton 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly I’d like to express immense gratitude for Professor Tia Blassingame and her invaluable support throughout the semester, along with Professor Kasper Kovitz, Professor Nancy Macko, Professor Amy Santoferraro and the faculty of Scripps’s Art Department for their encouragement during his time at the Claremont Colleges. I’m indebted with innumerable amounts of appreciation for my community and family for supporting me unconditionally throughout these last four years at the Claremont Colleges. -

We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 This

We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 This exhibition presents the work of more than forty artists and activists who built their careers—and committed themselves to political change—during a time of social tumult in the United States. Beginning in the 1960s, a number of movements to combat social injustice emerged, with the Black Power, Civil Rights, and Women’s Movements chief among them. As active participants in the contemporary art world, the artists in this exhibition created their own radical feminist thinking—working broadly, on multiple fronts—to combat sexism, racism, homophobia, and classism in the art world and within their local communities. As the second-wave Feminist Movement gained strength in the 1970s, women of color found themselves working with, and at times in opposition to, the largely white, middle- class women primarily responsible for establishing the tone, priorities, and methods of the fight for gender equity in the United States. Whether the term feminism was used or not— and in communities of color, it often was not—black women envisioned a revolution against the systems of oppression they faced in the art world and the culture at large. The artists of We Wanted a Revolution employed the emerging methods of conceptual art, performance, film, and video, along with more traditional forms, including printmaking, photography, and painting. Whatever the medium, their innovative artmaking reflected their own aesthetic, cultural, and political priorities. Favoring radical transformation over reformist gestures, these activist artists wanted more than just recognition within the existing professional art world. Instead, their aim was to revolutionize the art world itself, making space for the many and varied communities of people it had largely ignored. -

The Shed Presents the Powerful Work of Howardena Pindell in a Solo Exhibition Examining Racism in America

THE SHED PRESENTS THE POWERFUL WORK OF HOWARDENA PINDELL IN A SOLO EXHIBITION EXAMINING RACISM IN AMERICA Featuring Pindell’s First Video Work in 25 Years, Commissioned by The Shed For more information, please contact: Howardena Pindell: Rope/Fire/Water On View October 16, 2020 – April 11, 2021 Christina Riley Publicist (646) 876-6865 [email protected] Howardena Pindell, Four Little Girls, 2020. Mixed media on canvas. 108 x 120 inches. Courtesy the artist and Garth Greenan Gallery, New York. NEW YORK, NY – September 21, 2020 – The Shed reopens October 16 with a solo exhibition, nearly four years in the making, featuring new work by Howardena Pindell that examines the violent, historical trauma of racism in America and the therapeutic power of art. With enhanced health and safety protocols, The Shed will welcome back visitors Thursdays through Sundays, with free admission to the exhibition through October 31. Howardena Pindell: Rope/Fire/Water, organized by Adeze Wilford, Assistant Curator at The Shed, is on view through April 11, 2021 and includes Pindell’s first video work in 25 years, as well as new large-scale paintings and several abstract paintings from earlier in her career. “Working on my commission for The Shed has been a very rewarding and healing experience,” said Howardena Pindell. “It allowed me to conceptualize an idea as a result of an experience I had as a child. I put it forth as a performance piece to a group of white women artists at the A.I.R. Gallery, where I was a founder in the early 1970s. -

Kerry James Marshall B

FLOOR 3 GRIEF AND GRIEVANCE Floor 3 Jean-Michel Basquiat b. 1960, Brooklyn, NY; d. 1988, New York, NY Procession, 1986 Acrylic on wood Private Collection Jean-Michel Basquiat was a self-taught artist who rose to rapid fame in the 1970s and ’80s. Known both for his graffiti work (signed as his alter ego, SAMO) as well as his immersion in hip-hop and new wave music scenes, Basquiat created vivid line drawings and paintings incorporating words, numbers, diagrams, logos, and accidental marks. In Basquiat’s work, both abstraction and figuration function as overt and coded social commentary, making use of bold formal gestures to address concepts of colonialism, class struggle, state authority, and police violence. Basquiat created several works reliant on the invocation of the grief caused by the historically disproportionate use of police force against Black communities, including the painting Untitled (1983), also widely known as The Death of Michael Stewart or Defacement. Stewart, a young Black artist, was attacked and murdered by police that year for allegedly tagging a wall of a downtown New York subway station. Distraught over Stewart’s death, Basquiat reflected: “It could have been me. It could have been me.” Basquiat’s reflection on mourning also extends to histories of the Black Atlantic. Procession (1986) depicts four Black silhouetted figures facing a figure painted in red, white, and blue and carrying a skull—a symbol repeated in many of his other works. Part of a body of work relating to the American South and the artist’s Haitian-Puerto Rican heritage, Procession calls to mind both the deep psychological pain of slavery in the region and the spiritual terrain of traditional jazz funerals, during which processions of mourners follow the remains of the deceased.