06 the State of Philippine Democracy 1987.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emindanao Library an Annotated Bibliography (Preliminary Edition)

eMindanao Library An Annotated Bibliography (Preliminary Edition) Published online by Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Honolulu, Hawaii July 25, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iii I. Articles/Books 1 II. Bibliographies 236 III. Videos/Images 240 IV. Websites 242 V. Others (Interviews/biographies/dictionaries) 248 PREFACE This project is part of eMindanao Library, an electronic, digitized collection of materials being established by the Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. At present, this annotated bibliography is a work in progress envisioned to be published online in full, with its own internal search mechanism. The list is drawn from web-based resources, mostly articles and a few books that are available or published on the internet. Some of them are born-digital with no known analog equivalent. Later, the bibliography will include printed materials such as books and journal articles, and other textual materials, images and audio-visual items. eMindanao will play host as a depository of such materials in digital form in a dedicated website. Please note that some resources listed here may have links that are “broken” at the time users search for them online. They may have been discontinued for some reason, hence are not accessible any longer. Materials are broadly categorized into the following: Articles/Books Bibliographies Videos/Images Websites, and Others (Interviews/ Biographies/ Dictionaries) Updated: July 25, 2014 Notes: This annotated bibliography has been originally published at http://www.hawaii.edu/cps/emindanao.html, and re-posted at http://www.emindanao.com. All Rights Reserved. For comments and feedbacks, write to: Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa 1890 East-West Road, Moore 416 Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Email: [email protected] Phone: (808) 956-6086 Fax: (808) 956-2682 Suggested format for citation of this resource: Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. -

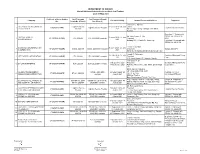

DEPARTMENT of ENERGY List of Valid and Subsisting Accredited Coal Traders As of 31 May 2021

DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY List of Valid and Subsisting Accredited Coal Traders as of 31 May 2021 Certificate of Accreditation Coal Transport Coal Transport Permit Company Period of Validity Contact Person and Address Supplier/s No. Permit No. (Form 1) No. (Form 2) Catherine C. Martinez DEUS-BENEDICAT CARRIERS Logistics Service 02 June 2020 - 01 June Owner 1 CT-2020-06-0442 Logistics Service Provider Logistics Service Provider ENTERPRISES Provider 2021 Km 37 Brgy. Pulong Buhangin, Sta. Maria, Bulacan Marcelino G. Temario with Mr. Jake Vincent S. Villa SSCMP No. VFO-2019- LAVYNJEX MINES 25 June 2020 - 24 June 2 CT-2020-06-0443(R) LMI-2020-06 LMI-2020-0001 onwards President 002® INCORPORATED 2021 Building 119 T. Padilla St., Cebu City Florentino C. Llorando with SSCMP No. 2018-001 Elenita B. Gumban SURIGAO COAL MARKETING 26 June 2020 - 25 June 3 CT-2020-06-0444(R) SCMC-2020-06 SCMC-2020-0001 onwards Chairman Surigao SSCMPs COOPERATIVE 2021 Murio St., Mangagoy, Bislig City Surigao del Sur Joseph C. Dyhengco 16 July 2020 - 15 July Semirara Mining and Power 4 JET POWER CORPORATION CT-2020-07-0445(R) JPC-2020-07 JPC-2020-0001 onwards President 2021 Corp. 808 Reina Regente St. Binondo, Manila John Louie N. Sy 19 September 2020 - Proprietor Semirara Mining and Power 5 SY LINK MARKETING CT-2020-09-0446(R) SLM-2020-09 SLM-2020-0001 onwards 18 September 2021 #20 Gov. Ramos Ave., Sta. Maria, Zamboanga Corporation City Maria Anna M. Agbunag VP - MIS, MMD, FMD, COT GLOBAL TRADE ENERGY GTrade-2020-0001 29 August 2020 - 28 Coaltrade Services 6 CT-2020-08-0447® GTrade-2020-08 Noel A. -

Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014

This event is dedicated to the Filipino People on the occasion of the five- day pastoral and state visit of Pope Francis here in the Philippines on October 23 to 27, 2014 part of 22- day Asian and Oceanian tour from October 22 to November 13, 2014. Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 ―Mercy and Compassion‖ a Papal Visit Philippines 2014 and 2015 2014 Contents About the project ............................................................................................... 2 About the Theme of the Apostolic Visit: ‗Mercy and Compassion‘.................................. 4 History of Jesus is Lord Church Worldwide.............................................................................. 6 Executive Branch of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines ....................................................................... 15 Vice Presidents of the Republic of the Philippines .............................................................. 16 Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines ............................................ 16 Presidents of the Senate of the Philippines .......................................................................... 17 Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the Philippines ...................................................... 17 Leaders of the Roman Catholic Church ................................................................ 18 Pope (Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome and Worldwide Leader of Roman -

Stories Captured by Word of Mouth Cultural Heritage Building Through Oral History

STORIES CAPTURED BY WORD OF MOUTH CULTURAL HERITAGE BUILDING THROUGH ORAL HISTORY Christine M. Abrigo Karen Cecille V. Natividad De La Salle University Libraries Oral History, still relevant? (Santiago, 2017) • Addresses limitations of documents • Gathers insights and sentiments • More personal approach to recording history Oral History in the Philippines (Foronda, 1978) There is a scarcity of studies and literatures on the status and beginning of oral history in the country. DLSU Libraries as repository of institutional and national memory Collects archival materials and special collections as they are vital sources of information and carry pertinent evidences of culture and history. Oral history is one of these archival materials. Purpose of this paper This paper intends to document the oral history archival collection of the De La Salle University (DLSU) Libraries; its initiatives to capture, preserve and promote intangible cultural heritage and collective memory to its users through this collection, and the planned initiatives to further build the collection as a significant contribution to Philippine society. ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION (OHC) OF THE DLSU LIBRARIES Provenance The core OHC came from the family of Dr. Marcelino A. Foronda, Jr., a notable Filipino historian and from the Center for Oral and Local History of the university, which was later named in his honor, hence, the Marcelino A. Foronda Jr. Center for Local and Oral History (MAFCLOH). Collection Profile FORMAT Print transcript Audio cassette tape Collection Source (in -

Martial Law and the Realignment of Political Parties in the Philippines (September 1972-February 1986): with a Case in the Province of Batangas

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 29, No.2, September 1991 Martial Law and the Realignment of Political Parties in the Philippines (September 1972-February 1986): With a Case in the Province of Batangas Masataka KIMURA* The imposition of martial lawS) by President Marcos In September 1972 I Introduction shattered Philippine democracy. The Since its independence, the Philippines country was placed under Marcos' au had been called the showcase of democracy thoritarian control until the revolution of in Asia, having acquired American political February 1986 which restored democracy. institutions. Similar to the United States, At the same time, the two-party system it had a two-party system. The two collapsed. The traditional political forces major parties, namely, the N acionalista lay dormant in the early years of martial Party (NP) and the Liberal Party (LP),1) rule when no elections were held. When had alternately captured state power elections were resumed in 1978, a single through elections, while other political dominant party called Kilusang Bagong parties had hardly played significant roles Lipunan (KBL) emerged as an admin in shaping the political course of the istration party under Marcos, while the country. 2) traditional opposition was fragmented which saw the proliferation of regional parties. * *MI§;q:, Asian Center, University of the Meantime, different non-traditional forces Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, Metro Manila, such as those that operated underground the Philippines 1) The leadership of the two parties was composed and those that joined the protest movement, mainly of wealthy politicians from traditional which later snowballed after the Aquino elite families that had been entrenched in assassination in August 1983, emerged as provinces. -

Covers Republic Act Numbers 11167-11372

Senate of the Philippines Linkages Update Volume 12 No. 3 17th Congress Series of 2019 This Linkages Update aims to provide information on legislations approved and enacted into law, bills passed on third reading by the Senate, outputs of Forums conducted by ILS, and other concerns of national importance. Presented in this issue are the Laws Passed during the Seventeenth Congress covering the period January 2019 to June 2019. This publication is a project of the Institutional Linkages Service (ILS) under the External Affairs and Relations Office. Contents Covers Republic Act Nos. 11167-11372 Researched and Encoded by : Ma. Teresa A. Castillo Reviewed and Administrative Supervision by : Dir. Julieta J. Cervo, CPA, DPA Note: The contents of this publication are those that are considered Important by the author/researcher and do not necessarily reflect those of the Senate, of its leadership or of its individual members. The Institutional Linkages Service is under the External Affairs and Relations headed by Deputy Secretary Enrique Luis D. Papa and Executive Director Diana Lynn Le-Cruz. Covers Republic Act Numbers 11167-11372 Provided below are the laws passed and approved by the President of the Philippines during the 3rd Regular Session of the 17th Congress: REPUBLIC ACT NO. 11167 “AN ACT INCREASING THE BED CAPACITY OF THE BILIRAN PROVINCIAL HOSPITAL IN ITS PROPOSED RELOCATION SITE IN BARANGAY LARRAZABAL, MUNICIPALITY OF NAVAL, PROVINCE OF BILIRAN, FROM SEVENTY-FIVE (75) TO TWO HUNDRED (200) BEDS, AND APPROPRIATING FUNDS THEREFOR” APPROVED INTO LAW ON JANUARY 3, 2019 REPUBLIC ACT NO. 11168 “AN ACT ALLOWING HOME ECONOMICS GRADUATES TO TEACH HOME ECONOMICS SUBJECTS AND HOME ECONOMICS-RELATED TECHNICAL-VOCATIONAL SUBJECTS IN ALL PUBLIC AND PRIVATE ELEMENTARY AND SECONDARY EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS, RESPECTIVELY, CONSISTENT WITH SECTION 8 OF REPUBLIC ACT NO. -

Women and Politics

WOMEN AND POLITICS Speech of former Senator Leticia Ramos Shahani at the Eminent Women in Politics Lecture Series of Miriam College Women and Gender Institute, Claro M. Recto Hall, Philippine Senate, Thursday, 26 April 2007 I should like to thank the Women and Gender Institute of Miriam College for inviting me to open this series of lectures entitled “Eminent Women in Politics”. The College, true to its pioneering tradition, is to be congratulated for daring to enter a controversial and complicated field of endeavor for women. It is certainly an honor to share the podium today with one of our respected Senators of the land – Senate President Manuel Villar – who is a shining example of what we expect our Senators to be – honest, experienced, dedicated to the progress of our people and country and it should be mentioned, a gender advocate. But Senator Villar does not really need this election plug from me since it looks certain that, with three weeks away from voting time, he will be one of the topnotchers in the coming election for Senators. It is also fitting that Miriam College uses this occasion to commemorate the 70 th anniversary of the Filipino women’s right to vote and be voted upon, a victory of those dynamic and patriotic women of the suffragette movement who enabled Filipino women to enter the mainstream of our nation’s political life not only to cast their vote but to stand for elective office. I do not forget that it is they who enabled me to run for public office when my own time came. -

April 2, 2016 Hawaii Filipino Chronicle 1

ApriL 2, 2016 hAwAii FiLipino ChroniCLe 1 ♦ APRIL 2, 2016 ♦ LEGAL NOTES Q & A TAX TIME F-1 STem Ayonon To LeAd KAuAi one Thing STudenTS CAn now FiLipino ChAmber oF iS CerTAin - STAy Longer CommerCe TAxeS PRESORTED HAWAII FILIPINO CHRONICLE STANDARD 94-356 WAIPAHU DEPOT RD., 2ND FLR. U.S. POSTAGE WAIPAHU, HI 96797 PAID HONOLULU, HI PERMIT NO. 9661 2 hAwAii FiLipino ChroniCLe ApriL 2, 2016 EDITORIALS FROM THE PUBLISHER Publisher & Executive Editor re you living on the financial Charlie Y. Sonido, M.D. Pinoy Cinema on edge? According to a recent poll Publisher & Managing Editor conducted by the Hawaii Apple- Chona A. Montesines-Sonido Display at Filipino seed Center for Law and Eco- Associate Editors Dennis Galolo | Edwin Quinabo nomic Justice, nearly half of A Contributing Editor Film Fest Hawaii residents are living pay- Belinda Aquino, Ph.D. veryone loves a good movie, whether it is science check to paycheck. What is alarming is that Creative Designer fiction, an action-packed thriller or romantic com- when broken down by ethnicity, the poll Junggoi Peralta shows that Filipinos comprise a whopping 78 percent of those Photography edy. Simply kill the lights, snuggle up next to your Tim Llena favorite person or persons, grab a bag of popcorn who live month to month! It just shows how financially pre- Administrative Assistant E and blissfully enjoy the next few hours. carious it is to live in Hawaii, especially when large unexpected Shalimar Pagulayan For those movie goers who prefer a night out, expenses hit. Columnists Carlota Hufana Ader attending a local film festival is a good venue to see a range of On a more positive note, Kauai residents are celebrating Emil Guillermo different movies with a certain theme. -

Title Martial Law and Realignment of Political Parties in the Philippines

Martial Law and Realignment of Political Parties in the Title Philippines(September 1972-February 1986): With a Case in the Province of Batangas Author(s) Kimura, Masataka Citation 東南アジア研究 (1991), 29(2): 205-226 Issue Date 1991-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/56443 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 29, No.2, September 1991 Martial Law and the Realignment of Political Parties in the Philippines (September 1972-February 1986): With a Case in the Province of Batangas Masataka KIMURA* The imposition of martial lawS) by President Marcos In September 1972 I Introduction shattered Philippine democracy. The Since its independence, the Philippines country was placed under Marcos' au had been called the showcase of democracy thoritarian control until the revolution of in Asia, having acquired American political February 1986 which restored democracy. institutions. Similar to the United States, At the same time, the two-party system it had a two-party system. The two collapsed. The traditional political forces major parties, namely, the N acionalista lay dormant in the early years of martial Party (NP) and the Liberal Party (LP),1) rule when no elections were held. When had alternately captured state power elections were resumed in 1978, a single through elections, while other political dominant party called Kilusang Bagong parties had hardly played significant roles Lipunan (KBL) emerged as an admin in shaping the political course of the istration party under Marcos, -

Jose Wright Diokno

Written by: NACIONAL, KATHERINE E. MANALO, RUBY THEZ D. TABILOG, LEX D. 3-H JOSE WRIGHT DIOKNO “Do not forget: We Filipinos are the first Asian people who revolted against a western imperial power, Spain; the first who adopted a democratic republican constitution in Asia, the Malolos Constitution; the first to fight the first major war of the twentieth century against another western imperial power, the United States of America. There is no insurmountable barrier that could stop us from becoming what we want to be.” Jose W. Diokno Jose “Pepe” Diokno was one of the advocates of human rights, Philippine sovereignty and nationalism together with some of the well-known battle-scarred fighters for freedom like Ninoy Aquino, Gasty Ortigas, Chino Roces, Tanny Tañada, Jovy Salonga, and few more. His life was that of a lover of books, education, and legal philosophy. He never refused to march on streets nor ague in courts. He never showcases his principles to get attention except when he intends to pursue or prove a point. He is fluent in several languages, and used some when arguing in courts, including English and Spanish. He became a Secretary of Justice when appointed by then President Diosdado Macapagal, and he was elected as a Senator of the Republic, who won the elections by campaigning alone. And during his entire political life, he never travelled with bodyguards nor kept a gun or used one. By the time he died, he was with his family, one of the things he held precious to his heart. FAMILY BACKGROUD The grandfather of Jose was Ananias Diokno, a general of the Philippine Revolutionary Army who served under Emilio Aguinaldo and who was later on imprisoned by American military forces in Fort Santiago together with Servillano Aquino, another Filipino General. -

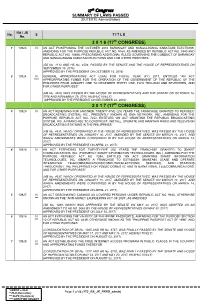

17Th Congress SUMMARY of LAWS PASSED (DUTERTE Administration)

17th Congress SUMMARY OF LAWS PASSED (DUTERTE Administration) RA / JR No. S T I T L E No. 2 0 1 6 (17th CONGRESS) 1 10923 N AN ACT POSTPONING THE OCTOBER 2016 BARANGAY AND SANGGUNIANG KABATAAN ELECTIONS, AMENDING FOR THE PURPOSE REPUBLIC ACT NO. 9164, AS AMENDED BY REPUBLIC ACT NO. 9340 AND REPUBLIC ACT NO. 10656, PRESCRIBING ADDITIONAL RULES GOVERNING THE CONDUCT OF BARANGAY AND SANGGUNIANG KABATAAN ELECTIONS AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES (SB No. 1112 AND HB No. 3504, PASSED BY THE SENATE AND THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ON SEPTEMBER 13, 2016) (APPROVED BY THE PRESIDENT ON OCTOBER 15, 2016) 2 10924 N GENERAL APPROPRIATIONS ACT (GAA) FOR FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2017, ENTITLED “AN ACT **** APPRORPRIATING FUNDS FOR THE OPERATION OF THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPINES FROM JANUARY ONE TO DECEMBER THIRTY ONE, TWO THOUAND AND SEVENTEEN, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES” (HB No. 3408, WAS PASSED BY THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES AND THE SENATE ON OCTOBER 19, 2016 AND NOVEMBER 28, 2016, RESPECTIVELY) (APPROVED BY THE PRESIDENT ON DECEMBER 22, 2016) 2 0 1 7 (17th CONGRESS) 3 10925 N AN ACT RENEWING FOR ANOTHER TWENTY-FIVE (25) YEARS THE FRANCHISE GRANTED TO REPUBLIC BROADCASTING SYSTEM, INC., PRESENTLY KNOWN AS GMA NETWORK, INC., AMENDING FOR THE PURPOSE REPUBLIC ACT NO. 7252, ENTITLED “AN ACT GRANTING THE REPUBLIC BROADCASTING SYSTEM, INC. A FRANCHISE TO CONSTRUCT, INSTALL, OPERATE AND MAINTAIN RADIO AND TELEVISION BROADCASTING STATIONS IN THE PHILIPPINES” (HB No. 4631, WHICH ORIGINATED IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, WAS PASSED BY THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ON JANUARY 16, 2017, AMENDED BY THE SENATE ON MARCH 13, 2017, AND WHICH AMENDMENTS WERE CONCURRED IN BY THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ON MARCH 14, 2017) (APPROVED BY THE PRESIDENT ON APRIL 21, 2017) 4 10926 N AN ACT EXTENDING FOR TWENTY-FIVE (25) YEARS THE FRANCHISE GRANTED TO SMART COMMUNICATIONS, INC. -

Portcalls; July 5 2021

2 • PortCalls JULY 5 ISSUE INDUSTRYNEWS MONDAY July 5, 2021 North Port operator INTERNATIONALINTERNATIONAL eyes 15.33% hike in ACESTAR SERVICESERVICE CORPORATIONCORPORATION cargo handling tariff SEA && AIRAIR • Manila North Harbour Port, MANILA TO [OSAKA • KOBE] via ONE MANILAMANILA TOTO SHANGHAISHANGHAI VESSEL VOY. LCT@12PM ETD ETAETA OSAOSA ETAETA UKBUKB VESSELVESSEL VOY.VOY. LCTLCT @12PM @12PM ETDETD ETAETA SHA SHA Inc. is seeking a 15.33% in- BALSA 114N 06/30 07/0307/03 07/0907/09 07/1507/15 ASAS ROMINAROMINA 0KD0SE0KD0SE 07/0107/01 07/0407/04 07/0907/09 crease in cargo-handling tariff MOL SUCCESS 125N 07/07 07/10 07/16 07/2207/22 OLYMPIAOLYMPIA 0KD0WE0KD0WE 07/0807/08 07/1107/11 07/1607/16 and passenger terminal fee in CALLAO BRIDGE 195N 07/14 07/17 07/2307/23 07/2907/29 MOUNTMOUNT BUTLERBUTLER 0KD10E0KD10E 07/1507/15 07/1807/18 07/2307/23 North Port, the domestic ter- BALSA 115N 07/21 07/2407/24 07/3007/30 08/0508/05 HANSAHANSA FRESENBURGFRESENBURG 21009E21009E 07/2207/22 07/2507/25 07/3007/30 minal in Manila North Harbor, MANILA TO SINGAPORE MANILAMANILA TOTO BUSANBUSAN VESSELVESSEL VOY.VOY. LCT@12PMLCT@12PM ETDETD ETAETA BUS BUS covering the period 2015 to 2020 VESSEL VOY. LCT@5PM ETDETD ETAETA SINSIN ALS FAUNA 102S 07/01 07/0807/08 07/1407/14 KMTCKMTC SHANGHAISHANGHAI 2108S2108S 06/2506/25 07/0307/03 07/1807/18 • The Supply Chain Management SEASPAN NEW YORK 024S024S 07/0807/08 07/1407/14 07/2007/20 HANSAHANSA FALKENBURGFALKENBURG 2110S2110S 07/0207/02 07/0707/07 07/2107/21 Association of the Philippines ALS FAUNA 103S 07/15 07/2307/23 07/2907/29 HYUNDAIHYUNDAI GRACEGRACE 0113N0113N 07/0707/07 07/1007/10 07/1907/19 and the Philippine Exporters SEASPAN NEW YORK 025S025S 07/2207/22 07/2907/29 08/0408/04 KMTCKMTC GWANGYANGGWANGYANG 2108S2108S 07/0907/09 07/1507/15 08/0108/01 Confederation, Inc.