The University of Tennessee Knoxville an Interview With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 Non Blondes What's up Abba Medley Mama

4 Non Blondes What's Up Abba Medley Mama Mia, Waterloo Abba Does Your Mother Know Adam Lambert Soaked Adam Lambert What Do You Want From Me Adele Million Years Ago Adele Someone Like You Adele Skyfall Adele Turning Tables Adele Love Song Adele Make You Feel My Love Aladdin A Whole New World Alan Silvestri Forrest Gump Alanis Morissette Ironic Alex Clare I won't Let You Down Alice Cooper Poison Amy MacDonald This Is The Life Amy Winehouse Valerie Andreas Bourani Auf Uns Andreas Gabalier Amoi seng ma uns wieder AnnenMayKantenreit Barfuß am Klavier AnnenMayKantenreit Oft Gefragt Audrey Hepburn Moonriver Avicii Addicted To You Avicii The Nights Axwell Ingrosso More Than You Know Barry Manilow When Will I Hold You Again Bastille Pompeii Bastille Weight Of Living Pt2 BeeGees How Deep Is Your Love Beatles Lady Madonna Beatles Something Beatles Michelle Beatles Blackbird Beatles All My Loving Beatles Can't Buy Me Love Beatles Hey Jude Beatles Yesterday Beatles And I Love Her Beatles Help Beatles Let It Be Beatles You've Got To Hide Your Love Away Ben E King Stand By Me Bill Withers Just The Two Of Us Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine Billy Joel Piano Man Billy Joel Honesty Billy Joel Souvenier Billy Joel She's Always A Woman Billy Joel She's Got a Way Billy Joel Captain Jack Billy Joel Vienna Billy Joel My Life Billy Joel Only The Good Die Young Billy Joel Just The Way You Are Billy Joel New York State Of Mind Birdy Skinny Love Birdy People Help The People Birdy Words as a Weapon Bob Marley Redemption Song Bob Dylan Knocking On Heaven's Door Bodo -

Sam Smith Og John Legend Med Ny Versjon Av Lay Me Down

09-03-2015 17:29 CET Sam Smith og John Legend med ny versjon av Lay Me Down I morgen slippes en ny og nydelig versjon av Lay Me Down hvor Sam Smith har med seg John Legend. Versjonen slippes i forbindelse med Comic Relief og deres Red Nose Day. Sangen er originalt fra Sam Smiths multiplatinumselgende debutalbum In The Lonely Hour, hvor denne nye versjonen blir sluppet til inntekt for Comic Relief. Førstkommende fredag gjester også Sam Smith Skavlan. Les full pressemelding her og hør den nye versjonen av Lay Me Down her: Se video på YouTube her FULL PRESSEMELDING: SAM SMITH AND JOHN LEGEND TO RELEASE OFFICIAL RED NOSE DAY SINGLE The multi award winning transatlantic megastars collaborate for Comic Relief Today (9th March 2015) Comic Relief is delighted to announce that Brit and Grammy award winning superstar Sam Smith will be collaborating with Oscar winner John Legend to record a very special version of Sam’s song Lay Me Down, making it the official single for Red Nose Day. The original song is from Sam’s multi-platinum debut album In the Lonely Hour and this new version is being re-released as a one off single to raise money for Comic Relief. The track is available from today to download on iTunes and the single is available to buy exclusively in Sainsbury’s. UK born Sam Smith and American born John Legend will perform the ballad together for the first and only time on Comic Relief – Face the Funny on Friday 13th March on BBC One, where their special one off performance will be broadcast live from the London Palladium. -

Avid Congratulates Its Many Customers Nominated for the 57Th Annual GRAMMY(R) Awards

December 10, 2014 Avid Congratulates Its Many Customers Nominated for the 57th Annual GRAMMY(R) Awards Award Nominees Created With the Company's Industry-Leading Music Solutions Include Beyonce's Beyonce, Ed Sheeran's X, and Pharrell Williams' Girl BURLINGTON, Mass., Dec. 10, 2014 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- Avid® (Nasdaq:AVID) today congratulated its many customers recognized as award nominees for the 57th Annual GRAMMY® Awards for their outstanding achievements in the recording arts. The world's most prestigious ceremony for music excellence will honor numerous artists, producers and engineers who have embraced Avid EverywhereTM, using the Avid MediaCentral Platform and Avid Artist Suite creative tools for music production. The ceremony will take place on February 8, 2015 at the Staples Center in Los Angeles, California. Avid audio professionals created Record of the Year and Song of the Year nominees Stay With Me (Darkchild Version) by Sam Smith, Shake It Off by Taylor Swift, and All About That Bass by Meghan Trainor; and Album of the Year nominees Morning Phase by Beck, Beyoncé by Beyoncé, X by Ed Sheeran, In The Lonely Hour by Sam Smith, and Girl by Pharrell Williams. Producer Noah "40" Shebib scored three nominations: Album of the Year and Best Urban Contemporary Album for Beyoncé by Beyoncé, and Best Rap Song for 0 To 100 / The Catch Up by Drake. "This is my first nod for Album Of The Year, and I'm really proud to be among such elite company," he said. "I collaborated with Beyoncé at Jungle City Studios where we created her track Mine using their S5 Fusion. -

Drama Recommended Monologues

Bachelor of Creative Arts (Drama) Recommended Monologues 1 AUDITION PIECES – FEMALE THREE SISTERS by Anton Chekhov IRINA: Tell me, why is it I’m so happy today? Just as if I were sailing along in a boat with big white sails, and above me the wide, blue sky and in the sky great white birds floating around? You know, when I woke up this morning, and after I’d got up and washed, I suddenly felt as if everything in the world had become clear to me, and I knew the way I ought to live. I know it all now, my dear Ivan Romanych. Man must work by the sweat of his brow whatever his class, and that should make up the whole meaning and purpose of his life and happiness and contentment. Oh, how good it must be to be a workman, getting up with the sun and breaking stones by the roadside – or a shepherd – or a school-master teaching the children – or an engine-driver on the railway. Good Heavens! It’s better to be a mere ox or horse, and work, than the sort of young woman who wakes up at twelve, and drinks her coffee in bed, and then takes two hours dressing…How dreadful! You know how you long for a cool drink in hot weather? Well, that’s the way I long for work. And if I don’t get up early from now on and really work, you can refuse to be friends with me any more, Ivan Romanych. 2 HONOUR BY JOANNA MURRAY-SMITH SOPHIE: I wish—I wish I was more… Like you. -

Host's Master Artist List

Host's Master Artist List You can play the list in the order shown here, or any order you prefer. Tick the boxes as you play the songs. Basement Jaxx1 Aaliyah Scissor Sisters Meat Loaf Black Eyed Peas Cndigans Biffy Clyro Jess Glynne Sam Smith Lewis Capaldi Rag N Bone Man Demi Lovato Limp Bizkit Soul II Soul Black Grape Elbow Culture Club Sugababes Another Level David Bowie Years & Years McFly Akon Miley Cyrus Phil Collins Bastille Prince Shawn Mendes Kings Of Leon JLS Stevie Wonder Rod Stewart Nelly Furtado Frankie Goes To Hollywood Ashanti Spandau Ballet Mary J Blige Dua Lipa Atomic Kitten Drake Anne-Marie Backstreet Boys Eminem Kooks Amy Winehouse Westlife Oasis Corona Shakira Corrs Copyright QOD Page 1/51 Team/Player Sheet 1 Good Luck! Aaliyah Spandau Ballet Cndigans Phil Collins Basement Jaxx1 Amy Winehouse Black Grape Limp Bizkit Years & Years Black Eyed Peas Kings Of Leon Atomic Kitten Biffy Clyro Corrs David Bowie Eminem Soul II Soul Nelly Furtado Miley Cyrus Dua Lipa Copyright QOD Page 2/51 Team/Player Sheet 2 Good Luck! Sugababes Meat Loaf Bastille Shakira Cndigans Prince Soul II Soul Dua Lipa Rod Stewart Kooks Ashanti Aaliyah Black Eyed Peas Drake Nelly Furtado Corrs JLS Jess Glynne Sam Smith Limp Bizkit Copyright QOD Page 3/51 Team/Player Sheet 3 Good Luck! Sam Smith Years & Years Bastille Kooks Kings Of Leon Cndigans Akon Ashanti Dua Lipa Black Grape Frankie Goes To Phil Collins Rod Stewart Nelly Furtado Mary J Blige Hollywood Amy Winehouse Meat Loaf Elbow Shawn Mendes Shakira Copyright QOD Page 4/51 Team/Player Sheet 4 Good -

Case 2:21-Cv-11039-BAF-APP ECF No. 6, Pageid

Case 2:21-cv-11039-BAF-APP ECF No. 6, PageID.<pageID> Filed 05/27/21 Page 1 of 4 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN SOUTHERN DIVISION SAM SMITH, #241580, Plaintiff, Civil Action No. 21-CV-11039 vs. HON. BERNARD A. FRIEDMAN N. MALOUF, et al., Defendants. _________________/ OPINION AND ORDER DISMISSING PLAINTIFF’S COMPLAINT Plaintiff, a state inmate at the Macomb Correctional Facility, has filed the instant civil rights complaint pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1983 against four state parole agents and supervisors. Plaintiff claims that defendants unconstitutionally revoked his parole. For the following reasons, the Court shall dismiss the complaint. Plaintiff alleges that in 2018, while he was on parole for an unspecified offense, his parole agent, defendant Malouf, told plaintiff that he would find a way to send plaintiff back to prison in retaliation for plaintiff’s complaints about Malouf. See Compl. at PageID.6. Plaintiff admits that in February 2020, he absconded from parole and was captured in July 2020. See id. at PageID.7. He asserts that there were lesser sanctions that could have been imposed, but because of defendants’ pre-existing desire to send him back to prison, they overcharged him with an unconstitutional Sex Offender Registration Act (“SORA”) violation and otherwise lied during parole revocation proceedings to ensure his reincarceration. See id. at PageID.8. Plaintiff seeks reinstatement of his parole, departmental discipline for defendants, $3 million in damages, and a cessation of retaliatory conduct. See id. Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 8(a) requires that a complaint set forth “a short and Case 2:21-cv-11039-BAF-APP ECF No. -

Andrew Dow James C

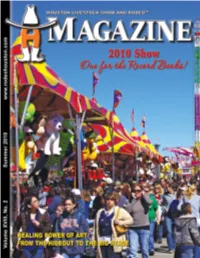

MAGAZINE COMMITTEE OFFICER IN CHARGE Pam Springer CHAIRMAN Gina Steere VICE CHAIRMEN Copy Editor Samantha Fewox Assignments Editor Ken Scott EDITORIAL BOARD Katie Lyons Melissa Manning Kenneth C. Moursund Jr. Tracy L. Ruffeno Marshall R. Smith III Breaking Barriers and Blasting Kristi Van Aken Past the 2 Million Mark ... 2 Todd Zucker PHOTOGRAPHERS Debbie Porter Lisa Van Etta REPORTERS Sonya Aston Stephanie Earthman Baird Scott Bumgardner 20102 Auction Buyers ... 5 Brandy Divin Generous buyers contribute to the future of Texas youth. Denise Doyle Kate Gunn Terrie James Sarah Langlois Brad Levy Lawrence S Levy Becky Lowicki Elizabeth Martin Gigi Mayorga-Wark Nan McCreary Crystal McKeon OutgoingO ti Vice ViP Presidents idt ... 10 Rochelle McNutt Lisa Norwood Six offi cers step down in 2010 with lasting memories of their tenure. Sandra Hollingsworth Smith Jodi Sohl OutgoingO Committee Chairmen ... 14 Emily Wilkinson Committee leadership changes hands. HOUSTON LIVESTOCK SHOW AND RODEO HealingH Power of Art ... 16 MAGAZINE COORDINATION Collaboration between Texas MARKETING & PUBLIC RELATIONS DIVISION Children’s Hospital and School MANAGING DIRECTOR, Art Committee honors special COMMUNICATIONS young artists. Clint Saunders COORDINATOR, COMMUNICATIONS Lauren Rouse DESIGN / LAYOUT FromF The Hideout Amy Noorian tot the Big Stage ... 18 STAFF PHOTOGRAPHERS The Eli Young Band credits the Francis M. Martin, D.V. M. RODEOHOUSTONTM performance as one Dave Clements of its biggest career performances. TheT Cover TheT total attendancea record Summer, Volume XVIII, No. 2, wasw set with is published quarterly by the 2,144,0772 visitors Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo. Committee Spotlights Copyright © 2010 Events & Functions ... tot the Houston Letters and comments should be sent to: LivestockL Show Marketing & Public Relations Division 20 TM Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo anda Rodeo in P. -

Sean Paul Step up Give It up to Me Mp3 Download

Sean paul step up give it up to me mp3 download Sean Paul Give It Up To Me () - file type: mp3 - download - bitrate: kbps. Sean Paul Ft Keyshia Cole Give It Up To Me. Now Playing. When You Gonna (give It Up To Me) (ft. Keyshia Cole). Artist: Sean Paul. MB. Convert Youtube Sean Paul Step Up Give It Up To Me to MP3 instantly. Free song download Sean Paul Give It Up To Me Feat Keyshia Cole Mp3. To start this download Keyshia Cole) (Disney Version for the film Step Up).mp3. 3gp & mp4. List download link Lagu MP3 SEAN PAUL FT KEYSHIA COLE GIVE IT UP TO ME ( Sean Paul Give It Up To Me Step Up Movie Chan. Вы можете бесплатно скачать mp3 Sean Paul Feat. Keyshia Cole – Give It Up To Me в высоком качестве kbit используйте кнопку скачать mp3. Free Sean Paul Give It Up To Me Feat Keyshia Cole Disney Version For The Film Step 3. Play & Download Size MB ~ ~ kbps. Download and Convert sean paul give it up to me to MP3 or MP4 for free! Paul - Give It Up To Me (Feat. Keyshia Cole) (Disney Version for the film Step Up). Sean Paul ft Keyshia Cole "Give It Up To Me" Remade by MD Basseliner on Reason Genre: Instrumental Hip Hop, MD Basseliner. times, 0 Play. WMG Give It Up To Me (Disney Version) Feat. Keyshia Cole Subscribe to Sean Paul's Channel Here. Buy Give It Up To Me: Read 2 Digital Music Reviews - На этой странице вы можете слушать Sean Paul Give It Up To Me Feat Keyshia Cole и скачивать бесплатно в формате mp3. -

Fat Chance, Charlie Vega / Crystal Maldonado

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 Fat Chance, 11 12 13 Charlie Vega 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 S31 N32 Maldonado_i-vi_1-346-r0mb.indd i 7/30/20 6:49:31 PM 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 Fat Chance, 15 16 17 18 Charlie Vega 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 S31 N32 Maldonado_i-vi_1-346-r0mb.indd iii 7/30/20 6:49:31 PM 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 Copyright © 2021 by Crystal Maldonado All Rights Reserved 09 HOLIDAY HOUSE is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. 10 Printed and bound in TK at TK. www.holidayhouse.com 11 First Edition 12 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 13 Library of Congress Cataloging‑in‑Publication Data 14 Names: Maldonado, Crystal, author. 15 Title: Fat chance, Charlie Vega / Crystal Maldonado. 16 Description: First edition. | New York : Holiday House, [2021] | Audience: Ages 14 and up. | Audience: Grades 10‑12. | Summary: Overweight 17 sixteen‑ year‑ old Charlie yearned for her first kiss while her perfect 18 best friend, Amelia, fell in love, so when she finally starts dating and learns the boy asked Amelia out first, she is devastated. 19 Identifiers: LCCN 2020015942 (print) | LCCN 2020015943 (ebook) | ISBN 20 9780823447176 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780823448906 (ebook) Subjects: CYAC: Self‑ esteem— Fiction. | Best friends— Fiction. | 21 Friendship— Fiction. | Overweight persons— Fiction. | Dating (Social 22 customs)— Fiction. -

In the United States District Court for the Middle District of Tennessee Nashville Division

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE NASHVILLE DIVISION MARK HALPER, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Case No. 3:16-cv-00567 ) Judge Steeh / Frensley SONY/ATV MUSIC PUBLISHING, LLC, ) et al., ) ) Defendants. ) REPORT AND RECOMMENDATION I. Introduction and Background This matter is before the Court upon a Motion to Dismiss and Incorporated Memorandum of Law filed pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6) by Defendants Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC, EMI April Music Inc., Gone Gator Music, Universal-Polygram International Tunes, Inc., Sony/ATV Songs LLC, and UMG Recordings, Inc. Docket No. 25. In support of their Motion, Defendants have contemporaneously filed the Declaration of Elizabeth Gonser with attached Exhibit. Docket No. 26. Plaintiff has filed a Response in Opposition to Defendants’ Motion. Docket No. 28. With leave of Court (Docket No. 31), Defendants have filed a Reply (Docket No. 29-1). Also with leave of Court (Docket Nos. 40, 43), Plaintiff has filed a Sur-Reply (Docket No. 44). Plaintiff, pro se, filed this copyright infringement action alleging that “Sam Smith, Capitol Recording artist, used and replicated phraseology and significant phrase ‘stay with me’ eight (8) times in the body of his mega hit song ‘Stay with Me’ thereby copying and infringing Case 3:16-cv-00567 Document 97 Filed 11/15/17 Page 1 of 18 PageID #: <pageID> upon the original musical production of Plaintiff Mark Halper whose original song ‘Don’t Throw Our Love Away’ written in April 1984 and musically recorded as a demo in a Nashville studio in February 1986 and a second demo musically recorded in 2013 that began in line 1 with the phraseology and significant phrase ‘stay with me’ and continued in line 2 with the phraseology ‘lay with me.’” Docket No. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home