Why India Could Do with One More Time Zone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberation War of Bangladesh

Bangladesh Liberation War, 1971 By: Alburuj Razzaq Rahman 9th Grade, Metro High School, Columbus, Ohio The Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971 was for independence from Pakistan. India and Pakistan got independence from the British rule in 1947. Pakistan was formed for the Muslims and India had a majority of Hindus. Pakistan had two parts, East and West, which were separated by about 1,000 miles. East Pakistan was mainly the eastern part of the province of Bengal. The capital of Pakistan was Karachi in West Pakistan and was moved to Islamabad in 1958. However, due to discrimination in economy and ruling powers against them, the East Pakistanis vigorously protested and declared independence on March 26, 1971 under the leadership of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. But during the year prior to that, to suppress the unrest in East Pakistan, the Pakistani government sent troops to East Pakistan and unleashed a massacre. And thus, the war for liberation commenced. The Reasons for war Both East and West Pakistan remained united because of their religion, Islam. West Pakistan had 97% Muslims and East Pakistanis had 85% Muslims. However, there were several significant reasons that caused the East Pakistani people to fight for their independence. West Pakistan had four provinces: Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan, and the North-West Frontier. The fifth province was East Pakistan. Having control over the provinces, the West used up more resources than the East. Between 1948 and 1960, East Pakistan made 70% of all of Pakistan's exports, while it only received 25% of imported money. In 1948, East Pakistan had 11 fabric mills while the West had nine. -

Help Is Just a Phone Call Away Help Is Just A

extras 1 NOW! extrasextrasTHE NOW! SPECIAL 8-PAGE PULL-OUT Yana ko HELPHELP ISIS dekhne yahan JUSTJUST AA aana PHONEPHONE CALLCALL AWAYAWAY SamSamSam RaiRaiRai andandand hishishis fourfourfour friendsfriendsfriends areareare notnotnot ininin governmentgovernmentgovernment service,service,service, THE butbutbut theytheythey areareare definitelydefinitelydefinitely FACTOR intointointo publicpublicpublic service...service...service... PROFILE ON pg 3 THE MIRACLE MUSHROOM EATERS CONGREGATE LOAN TURN TO pg 4 FOR DETAILS MELA’S LOST ALL ITS OM THE SIKKIM JOINS HANDS TO MANTRA FOR MAZAA BRING SUNSHINE TO THE ON pg 3 AUTUMNAL YEARS WEEKEND - TURN TO pg 4 FOR DETAILS - BLUES LIVE IN CONCERT! 6 & 7 MAY 2003 ORGANISED BY THE RANIPOOL YOUTH 7 extras 2 Panorama presents extraneous Color Lab THE GANGTOK STATE OF MIND GOOD AFTERNOON, GANGTOK BAZAAR Buzz pic KARCHOONG DIYALI . VOICE MAIL? vidently this Bazaar ‘Booze’ E(phonetic for Buzz)column now seems kind of incomplete without the mobile service run- ning on 22 lakhs handsets in India. Billing and charges for FREE SMS aside, has anyone used the VMS service promised on the numerous hoardings around town? A friend tried and Service? Dhundte reh jaoge!! a NOW! pic. he’s still trying. Why won’t he get the message that M is for expected over the coming minimize risks. The State gov- Mute NOT Mail in the VMS. months, some guidelines have to ernment here needs to take Information age indeed. How be set. A meeting has been called quick and preventive action be- about a night of heavy rain and for health workers and others on fore we face an epidemic we phone numbers get inter- the 1st May. -

Class-6 Chapter-13 (Geography) a Globe, Latitudes and Longitudes I

CLASS-6 CHAPTER-13 (GEOGRAPHY) A GLOBE, LATITUDES AND LONGITUDES I. Tick the correct option. 1. The Earth’s axis is: (a). an imaginary line that horizontally divides the Earth (b). an angular line that runs across the Tropic of Cancer (c). an imaginary line on which the Earth rotates Ans: (c) 2. The Torrid Zone lies between the: (a) Arctic Circle and Antarctic Circle (b) Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn (c). North Pole and South Pole Ans: (b) 3. The total number of meridians is (a) 340 (b) 360 (c) 180 Ans: (b) 4. The Equator is also known as the (a) Great Circle (b) Meridian (c) Ante meridian Ans: (a) 5. The longitude that determines the Indian Standard Time is (a) 00 (b) 1800 (c) 820 30’E Ans: (a) II. State whether the following statements are true or false and rewrite the incorrect statements to correct them. 1. All lines of longitude are circles. True 2. The temperate Zone is the hottest zone. False Ans: The Torrid Zone is the hottest zone. 3. ‘Geod’ is the term used to describe the shape of the Earth. True 4. The world is divided into 28 time zones. False Ans: The world is divided into 24 time zone. 5. The Antarctic Circle lies in the Southern Hemisphere. True III. Answer the following in one sentence. 1. What is a globe? Ans: A globe is a round model of the Earth that shows its shapes, landforms and directions as they truly relate to one another. 2. Name the heat zone in which the Equator is located? Ans: Torrid Zone in which the Equator is located. -

Earthquake in Sikkim, India

EHA, WHO, SEARO Situation Report (SR-1) 19 September 2011 Emergency and Humanitarian Action (EHA) Unit World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for South East Asia (SEARO) Earthquake in Sikkim, India Highlights • At least 21 people have been killed, 16 in India, and 5 in Nepal and over 100 are injured after an earthquake measuring 6.8 on the Ric hter Scale shook Sikkim on Sunday e vening, 18 September 2011. • Strong tremors were a lso felt in parts of North and East India and parts of Bangladesh and Nepal, causing widespread panic. The epicenter of the quake is said to be just 64 kilometer North-West of Gangtok. • Government organizations are trying their best to carry out rescue and relief operations and are conducting rapid damage assessments in remote areas. • WHO SEARO and Country Offices are in close contact with concerned ministries, monitoring the situation and standby to support emergency supplies and teams as needed. Earthquake Report Major Earthquake Time: 6.10 pm; Indian Standard Time; (12 :40 GMT) Richter Scale: 6.8 (USGS) Epicenter: 64 Kilometers North-West of Gangtok Depth: 20+ Kilometers below earth surface After Shocks Three after shocks measuring 5.7, 5.1 and 4.6 Richter Scale were felt after the major Earthquake. Page 1 of 5 EHA, WHO, SEARO Situation Report (SR-1) 19 September 2011 Incident sit mapping Caption: Map showing the epicenter of the major earthquake Situation Analysis India India was worst affected with at least 16 people killed. Seven people were reportedly killed in Sikkim, out of which two a t Singtham, one at Dikchu in Ea st Sikkim district and another a t Mangan. -

Potential Saving in Lighting Energy Due to Advancement In

Proceedings of Building Simulation 2011: 12th Conference of International Building Performance Simulation Association, Sydney, 14-16 November. POTENTIAL SAVINGS IN LIGHTING ENERGY DUE TO ADVANCEMENT IN INDIAN STANDARD TIME: AN ENQUIRY IN CONTEXT OF COMMERCIAL OFFICE SPACES IN INDIA. Padmini Rajaram1, Prof. Rajan Rawal1, 1Faculty of Design, CEPT University, Ahmedabad, India. October. This suggested savings in lighting energy ABSTRACT consumption by 0.7 %( Karasu, 2010). Similarly, The study aims at quantifying the savings in lighting evaluating DST for Jordan, (Momani et al.,2008) energy consumption for office buildings in India due studied on electricity consumption in two methods. to the permanent advancement of Indian standard First, a survey was done for residential and time from +0530 to +0600 GMT. The study initiates commercial sectors, and then overall energy by walk through energy audit to evaluate lighting generation was determined by monitoring daily load load and occupancy details for Ahmedabad and curves during DST. This suggested that there would Kolkata. This data is used to develop reference be savings if DST is implemented from April to models for simulations and determine lighting energy August with 30 minute permanent shift’. consumption. The time advancement is analyzed by shifting occupancy schedules for office spaces, hence However, analysing the impact of daylighting on parametric combinations of occupancy schedules peak electrical demand,(Selkowitz et al., 1983) with different floor plate sizes, aspect ratios, window analysed fenestrations, building envelop and lighting wall ratio with lighting controls are analyzed. Results controls in which hourly analysis was done for all from these models show 6.29% savings in the perimeter and core zones, It resulted that lighting lighting energy consumption. -

Energy Savings by Modification of Indian Standard Time

International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT) ISSN: 2278-0181 Vol. 4 Issue 02, February-2015 Energy Savings by Modification of Indian Standard Time Shriniket Patil Vijay Saraf Electrical Engineering Department, Electrical Engineering Department, Sardar Patel College of Engineering, Sardar Patel College of Engineering, Mumbai - 400058 Mumbai - 400058 Abstract — India currently faces a large energy deficit. This is consumption. Section V explains the energy savings that primarily associated with the evening peak load demands stems from using the method. Section VI lists the other which are not met. The major challenge for us is to meet those benefits that accrue from the approach. demands in a viable and economical manner. The insufficiencies should be fulfilled in the shortest period II. REVIEW OF AVAILABLE OPTIONS possible. Along with searching for new resources, we should also manage the existing ones. Many developed countries are In this section we review the rationales for introducing employing strategies for this based on modifications of their multiple time zones and daylight saving time (DST) and for standard time. This paper identifies the economically rejecting both . In the northern hemisphere, DST involves reasonable solution of advancing Indian Standard Time (IST) setting clocks ahead by an hour in spring and setting them by half an hour to combat the challenge of energy deficit that back by an hour in the fall. In the southern hemisphere, the India faces. Advancing the Indian Standard Time (IST) by two adjustments are reversed. We review an alternative, in half an hour will provide us with more daylight. In this paper, we propose to advance the IST by half an hour and bring it effect a year-long DST, which avoids the risks associated six hours ahead of Universal Coordinated Time. -

Eastern Time

2 OakridgeMUN II - Official Worldwide Schedule Booklet Worldwide Schedules UTC-08:00 / Pacific Time UTC-05:00 / Eastern Time UTC+01:00 / Central European Time UTC+05:30 / Indian Standard Time UTC+08:00 / Central Indonesian Time Other Time Zones For time zones not listed here, please click on the following links. When you arrive on the webpage, adjust the time zone to yours by clicking “Change your Location” under “Converted Time”. DAY 1 Opening Ceremonies Committee Session 1 Committee Session 2 Committee Session 3 Delegate Social DAY 2 Committee Session 4 Committee Session 5 Committee Session 6 Closing Ceremonies 3 OakridgeMUN II - Official Worldwide Schedule Booklet Pacific Time PLEASE NOTE: On Sunday, March 14th at 2:00AM PST, the time will shift forward one hour due to Daylight Savings Time. Therefore, on March 14th, the time zone would no longer be in Pacific Standard Time (PST; UTC-08:00); it would be in Pacific Daylight Time (PDT; UTC-07:00). Principle Cities: Vancouver, Seattle, Los Angeles, Tijuana Day 1 - Saturday, March 13th, 2021 Pacific Standard Time (PST), UTC-08:00 Time Activity 8:00 AM - 9:00 AM Opening Ceremonies - Opening Remarks - The Values of Oakridge - Keynote Speaker - Housekeeping Rules 9:00 AM - 11:00 AM Committee Session I - Committee, Staff and Delegate introductions - Choosing between the topics - Start of first chosen debate topic 11:00 AM - 12:00 PM Lunch Break 12:00 PM - 2:00 PM Committee Session II - Continued debate of first chosen debate topic - Brainstorming + Drafting Resolution Paper 2:00 PM - 2:45 -

2 Time Zones in India

2 Time Zones in India drishtiias.com/printpdf/2-time-zones-in-india Why in News? Recently Council of Scientific & Industrial Research’s National Physical Laboratory (CSIR-NPL), which maintains Indian Standard Time (IST), published a research article describing the necessity of two time zones. Suggesting two time zones and two ISTs in India: IST-I for most of India and IST- II for the Northeastern region – separated by difference of one hour IST-I, covering the regions falling between longitudes 68°7′E and 89°52′E and IST-II covering the regions between 89°52′E and 97°25′E. Who is Demanding? Northeast have long complained about the effect of a single time zone on their lives and their economies. In 2006, India’s federal planning commission recommended the division of the country into two time zones. National Physical Laboratory (NPL) - India’s official timekeeper - has supported a long standing demand for a separate time zone for eastern states Time zone Scottish-born Canadian Sir Sandford Fleming proposed a worldwide system of time zones in 1879. Eventually in 1884 International meridian conference adopted a 24 hour day. Countries across the world keep different times because of Earth’s rotation and revolution around the Sun. As Earth turns by 15° around its axis, time changes by one hour; a 360º-degree rotation yields 24 hours. As a result, the world is divided into 24 time zones shifted by one hour each. Indian Standard Time 1/4 IST is based on longitude 82.5°, which passes through Mirzapur, near Allahabad in Uttar Pradesh. -

Should India Adopt Two Time Zones? | 1

Should India adopt two time zones? | 1 Table of Contents 1 Theme: 2 In Favor – India should adopt two time zones: 3 Against – India should not adopt two time zones: 4 Facts: 5 International Scenario: 6 Conclusion: 7 Get updates from GD Ideas 8 New Topic suggestions Theme: Time Zone refers to the local time of a region or a country. Indian Standard Time (IST) is the time observed throughout India, with a time offset of +05:30. India has considered multiple time zones a few times but didn’t make a final decision yet. In Favor – India should adopt two time zones: Eastside of India is facing problems with IST. India Stretches for about 3000km from west to east which shows India should have two to three time zones ideally. The Time difference between the westernmost and easternmost part of India is approximately two hours and as a result, Sunrises as well as sets early in the east than in the rest of the country. In the North-East, the sun rises at approx. four in the morning and sets at about four in the evening in the winter. By the time that people start their work, half of the daylight is already wasted. In winter, this thing becomes even more problematic and results in more electricity consumption and lag in economic development in comparison to other states. Many activists, industrialists, and common people have complained about the effect of IST on their normal daily life. Eastern India is blessed with an abundance of minerals, but still, itlags in the economic development from the rest of the country because of the less working hours. -

Necessity of 'Two Time Zones: IST-I (UTC + 5:30 H) and IST-II (UTC + 6:30 H)' in India and Its Implementation

GENERAL ARTICLES Necessity of ‘two time zones: IST-I (UTC + 5 : 30 h) and IST-II (UTC + 6 : 30 h)’ in India and its implementation Lakhi Sharma, S. De, P. Kandpal, M. P. Olaniya, S. Yadav, T. Bhardwaj, P. Thorat, S. Panja, P. Arora, N. Sharma, A. Agarwal, T. D. Senguttuvan, V. N. Ojha and D. K. Aswal* A strong demand of a separate time zone by northeast populace has been a matter of great debate for a very long period. However, no implementable solution to this genuine problem has yet been proposed. The CSIR-National Physical Laboratory, CSIR-NPL (the National Measurement Insti- tute, NMI, of India and custodian of Indian Standard Time, IST) proposes an implementable solu- tion that puts the country in two time zones: (i) IST-I (UTC + 5 : 30 h, represented by longitude passing through 82°33′E) covering the regions falling between longitude 68°7′E and 89°52′E and (ii) IST-II (UTC + 6 : 30 h, represented by longitude passing through 97°30′E) encompassing the regions between 89°52′E and 97°25′E. The proposed demarcation line between IST-I and IST-II, falling at longitude 89°52′E, is derived from analyses of synchronizing the circadian clocks to normal office hours (9 : 00 a.m. to 5 : 30 p.m.). This demarcation line passes through the border of West Bengal and Assam and has a narrow spatial extension, which makes it easier to implement from the railways point of view. Once approved, the implementation would require establishment of a laboratory for ‘Primary Time Ensemble – II’ generating IST-II in any of the north-eastern states, which would be equivalent to the existing ‘Primary Time Ensemble-I’ at CSIR-NPL, New Delhi. -

Moca 001421.Pdf

Ministry of Civil Aviation Compendium of Central Government Services and Regulations for Greenfield Airport December 2011 Compendium of Central Government Services and Regulations for Greenfield Airport Abbreviations ACRONYM Definition AAI Airports Authority of India AERA Airports Economic Regulatory Authority AFRRO Assistant Foreign Regional Registration Offices AFS Aeronautical Fixed Services AIS Aeronautical Information Service AGA Aerodrome and Ground Aids AIU Air Intelligence Unit AMO Aeronautical meteorological offices AMS Aeronautical Meteorological Stations AMSL Above Mean Sea Level APHO Airport Health Organization APIS Advanced Passenger Information System ASC Airport Security Committee ASDA Accelerate-Stop Distance Available ASG Assistant Secretary General ASP Airport Security Program ATC Air Traffic Controller ATM Air Traffic Management ATR Avions de Transport Regional ATS Air Traffic Services AVSEC Aviation Security BCAS Bureau of Civil Aviation Security CAR Civil Aviation Requirements CASO Civil Aviation Safety Officer [2] Compendium of Central Government Services and Regulations for Greenfield Airport ACRONYM Definition CBEC Central Board of Excise and Customs CCTV Closed Circuit Television Surveillance CISF Central Industrial Security Force CNS Communication Navigation Surveillance COSCA Commissioner of Security CPWD Central Public Works Department DADF Department of Animal Husbandry, Dairying and Fisheries DDO District Development Officer DGCA Directorate General of Civil Aviation DGHS Directorate General Health Services -

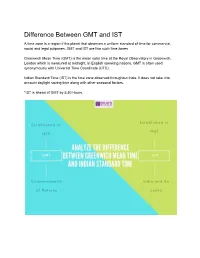

Difference Between GMT and IST

Difference Between GMT and IST A time zone is a region if the planet that observes a uniform standard of time for commercial, social and legal purposes. GMT and IST are two such time zones Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) is the mean solar time at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London which is measured at midnight. In English speaking nations, GMT is often used synonymously with Universal Time Coordinate (UTC). Indian Standard Time (IST) is the time zone observed throughout India. It does not take into account daylight saving time along with other seasonal factors. *IST is ahead of GMT by 5:30 Hours. In this article, we will examine the differences between the GMT (Greenwich Mean Time) and IST (Indian Standard Time). They both are recurring terms under the Geography segment of the IAS Exam. Differences between GMT and IST GMT (Greenwich Mean Time) IST (Indian Standard Time) The Greenwich Mean Time was The Indian Standard Time was established by the Royal Observatory in established as the official time zone 1675 with the purpose of assisting of India upon its independence on navigators at sea. August 15th, 1947 When calculating GMT it is considered The IST is calculated on the basis of equivalent to UT1 (the modern form of a clock tower in Mirzapur (with mean solar time at 0° longitude), but this coordinates 25.15° North Latitude meaning can differ from UTC by up to 0.9 and 82.58° East longitude). seconds. Because of Earth's uneven angular Official time signals are generated by velocity in its elliptical orbit, GMT is rarely the Time and Frequency Standards the exact moment the Sun crosses the Laboratory at the National Physical Greenwich meridian Laboratory in New Delhi, for both commercial and official use.