Ethno-Religiosity in Orthodox Christianity: a Source of Solidarity & Multiculturalism in American Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Serbian Orthodox Church in the USA Church Assembly—Sabor 800 Years of Autocephaly of the Serbian Orthodox Church: “Endowed by God, Treasured by the People”

Serbian Orthodox Church in the USA Church Assembly—Sabor 800 Years of Autocephaly of the Serbian Orthodox Church: “Endowed by God, Treasured by the People” August 1, 2019 Holy Despot Stephen the Tall and Venerable Eugenia (Lazarevich) LIBERTYVILLE STATEMENT OF THE PRESIDENTS OF THE CHURCH ASSEMBLY-SABOR REGARDING THE CONSTITUTION AND RELATED GOVERNING DOCUMENTS To the Very Reverend and Reverend Priests and Deacons, Venerable Monastics, the Members and Parishioners of the Church-School Congregations and Mission Parishes of the Serbian Orthodox Dioceses in the United States of America Beloved Clerics, Brothers and Sisters in Christ, As we have received numerous questions and concerns regarding the updated combined version of the current Constitution, General Rules and Regulations and Uniform Rules and Regulations for Parishes and Church School Congregations of the Serbian Orthodox Dioceses in the United States of America, that was published and distributed to all attendees and received by such on July 16, 2019 during the 22nd Church Assembly-Sabor, we deemed it necessary and appropriate to provide answers to our broader community regarding what was updated and why. The newly printed white bound edition is a compilation of all three prior documents, inclusive of past amendments and updated decisions rendered by previous Church Assemblies and the Holy Assembly of Bishops of the Serbian Orthodox Church. This was done in accordance with the May 7/24, 2018, HAB No. 45/MIN.171 decision of the Holy Assembly of Bishops of our Mother Church, the Serbian Orthodox Church, to whom we are and shall forever remain faithful. In terms of updates, there are two main categories: 1) the name change (i.e. -

Fewer Americans Affiliate with Organized Religions, Belief and Practice Unchanged

Press summary March 2015 Fewer Americans Affiliate with Organized Religions, Belief and Practice Unchanged: Key Findings from the 2014 General Social Survey Michael Hout, New York University & NORC Tom W. Smith, NORC 10 March 2015 Fewer Americans Affiliate with Organized Religions, Belief and Practice Unchanged: Key Findings from the 2014 General Social Survey March 2015 Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Most Groups Less Religious ....................................................................................................................... 3 Changes among Denominations .................................................................................................................. 4 Conclusions and Future Work....................................................................................................................... 5 About the Data ............................................................................................................................................. 6 References ..................................................................................................................................................... 7 About the Authors ....................................................................................................................................... -

Russian Orthodoxy and Women's Spirituality In

RUSSIAN ORTHODOXY AND WOMEN’S SPIRITUALITY IN IMPERIAL RUSSIA* Christine D. Worobec On 8 November 1885, the feast day of Archangel Michael, the Abbess Taisiia had a mystical experience in the midst of a church service dedicated to the tonsuring of sisters at Leushino. The women’s religious community of Leushino had recently been ele vated to the status of a monastery.1 Conducting an all-women’s choir on that special day, the abbess became exhilarated by the beautiful refrain of the Cherubikon hymn, “Let us lay aside all earthly cares,” and envisioned Christ surrounded by angels above the iconostasis. She later wrote, “Something was happening, but what it was I am unable to tell, although I saw and heard every thing. It was not something of this world. From the beginning of the vision, I seemed to fall into ecstatic rapture Tears were stream ing down my face. I realized that everyone was looking at me in astonishment, and even fear....”2 Five years later, a newspaper columnistwitnessedasceneinachurch in the Smolensk village of Egor'-Bunakovo in which a woman began to scream in the midst of the singing of the Cherubikon. He described “a horrible in *This book chapter is dedicated to the memory of Brenda Meehan, who pioneered the study of Russian Orthodox women religious in the modern period. 1 The Russian language does not have a separate word such as “convent” or nunnery” to distinguish women’s from men’s monastic institutions. 2 Abbess Thaisia, 194; quoted in Meehan, Holy Women o f Russia, 126. Tapestry of Russian Christianity: Studies in History and Culture. -

Genetics of the Peloponnesean Populations and the Theory of Extinction of the Medieval Peloponnesean Greeks

European Journal of Human Genetics (2017) 25, 637–645 Official journal of The European Society of Human Genetics www.nature.com/ejhg ARTICLE Genetics of the peloponnesean populations and the theory of extinction of the medieval peloponnesean Greeks George Stamatoyannopoulos*,1, Aritra Bose2, Athanasios Teodosiadis3, Fotis Tsetsos2, Anna Plantinga4, Nikoletta Psatha5, Nikos Zogas6, Evangelia Yannaki6, Pierre Zalloua7, Kenneth K Kidd8, Brian L Browning4,9, John Stamatoyannopoulos3,10, Peristera Paschou11 and Petros Drineas2 Peloponnese has been one of the cradles of the Classical European civilization and an important contributor to the ancient European history. It has also been the subject of a controversy about the ancestry of its population. In a theory hotly debated by scholars for over 170 years, the German historian Jacob Philipp Fallmerayer proposed that the medieval Peloponneseans were totally extinguished by Slavic and Avar invaders and replaced by Slavic settlers during the 6th century CE. Here we use 2.5 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms to investigate the genetic structure of Peloponnesean populations in a sample of 241 individuals originating from all districts of the peninsula and to examine predictions of the theory of replacement of the medieval Peloponneseans by Slavs. We find considerable heterogeneity of Peloponnesean populations exemplified by genetically distinct subpopulations and by gene flow gradients within Peloponnese. By principal component analysis (PCA) and ADMIXTURE analysis the Peloponneseans are clearly distinguishable from the populations of the Slavic homeland and are very similar to Sicilians and Italians. Using a novel method of quantitative analysis of ADMIXTURE output we find that the Slavic ancestry of Peloponnesean subpopulations ranges from 0.2 to 14.4%. -

The Beginnings of the Romanian Autocephalous Orthodox Church

Proceedings of SOCIOINT 2019- 6th International Conference on Education, Social Sciences and Humanities 24-26 June 2019- Istanbul, Turkey THE BEGINNINGS OF THE ROMANIAN AUTOCEPHALOUS ORTHODOX CHURCH Horia Dumitrescu Pr. Assist. Professor PhD., University of Piteşti, Faculty of Theology, Letters, History and Arts/ Centre for Applied Theological Studies, ROMANIA, [email protected] Abstract The acknowledgment of autocephaly represents a historical moment for the Romanian Orthodox Church, it means full freedom in organizing and administering internal affairs, without any interference or control of any church authority from outside. This church act did not remove the Romanian Orthodox Church from the unity of ecumenical Orthodoxy, but, on the contrary, was such as to preserve and ensure good relations with the Ecumenical Patriarchate and all other Sister Orthodox Churches, and promote a dogmatic, cult, canonical and work unity. The Orthodox Church in the Romanian territories, organized by the foundation of the Metropolis of Ungro-Wallachia (1359) and the Metropolis of Moldavia and Suceava (1401), became one of the fundamental institutions of the state, supporting the strengthening of the ruling power, to which it conferred spiritual legitimacy. The action of formal recognition of autocephaly culminated in the Ad Hoc Divan Assembly’s 1857 vote of desiderata calling for “recognition of the independence of the Eastern Orthodox Church, from the United Principalities, of any Diocesan Bishop, but maintaining unity of faith with the Ecumenical Church of the East with regard to the dogmas”. The efforts of the Romanian Orthodox Church for autocephaly were long and difficult, knowing a new stage after the Unification of the Principalities in 1859 and the unification of their state life (1862), which made it necessary to organize the National Church. -

Relationships Between Religious Denomination, Quality of Life

Journal of Global Catholicism Volume 2 Article 3 Issue 1 African Catholicism: Retrospect and Prospect December 2017 Relationships Between Religious Denomination, Quality of Life, Motivation and Meaning in Abeokuta, Nigeria Mary Gloria Njoku Godfrey Okoye University, [email protected] Babajide Gideon Adeyinka ICT Polytechnic Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/jgc Part of the African Studies Commons, Anthropology Commons, Catholic Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Community Psychology Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Developmental Psychology Commons, Health Psychology Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, Multicultural Psychology Commons, Personality and Social Contexts Commons, Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Regional Sociology Commons, and the Transpersonal Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Njoku, Mary Gloria and Adeyinka, Babajide Gideon (2017) "Relationships Between Religious Denomination, Quality of Life, Motivation and Meaning in Abeokuta, Nigeria," Journal of Global Catholicism: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 3. p.24-51. DOI: 10.32436/2475-6423.1020 Available at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/jgc/vol2/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Global Catholicism by an authorized editor of CrossWorks. 34 MARY GLORIA C. NJOKU AND BABAJIDE GIDEON ADEYINKA Relationships Between Religious Denomination, Quality of Life, Motivation and Meaning in Abeokuta, Nigeria Mary Gloria C. Njoku holds a masters and Ph.D. in clinical psychology and an M.Ed. in information technology. She is a professor and the dean of the School of Postgraduate Studies and the coordinator of the Interdisciplinary Sustainable Development Research team at Godfrey Okoye University Enugu, Nigeria. -

1 ETHNICITY and JEWISH IDENTITY in JOSEPHUS by DAVID

ETHNICITY AND JEWISH IDENTITY IN JOSEPHUS By DAVID McCLISTER A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2008 David McClister 2 To the memory of my father, Dorval L. McClister, who instilled in me a love of learning; to the memory of Dr. Phil Roberts, my esteemed colleague; and to my wife, Lisa, without whose support this dissertation, or much else that I do, would not have been possible. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I gladly recognize my supervisory committee chair (Dr. Konstantinos Kapparis, Associate Professor in the Classics Department at the University of Florida). I also wish to thank the other supervisory commiteee members (Dr. Jennifer Rea, Dr. Gareth Schmeling, and Dr. Gwynn Kessler as a reader from the Religious Studies Department). It is an honor to have their contributions and to work under their guidance. I also wish to thank the library staff at the University of Florida and at Florida College (especially Ashley Barlar) who did their work so well and retrieved the research materials necessary for this project. I also wish to thank my family for their patient indulgence as I have robbed them of time to give attention to the work necessary to pursue my academic interests. BWGRKL [Greek] Postscript® Type 1 and TrueTypeT font Copyright © 1994-2006 BibleWorks, LLC. All rights reserved. These Biblical Greek and Hebrew fonts are used with permission and are from BibleWorks, software for Biblical -

Christianity Questions

Roman Catholics of the Middle Ages shared the belief that there was Name one God, and that he created the universe. They believed that God sent his son, Jesus, to Earth to save mankind. They believed that God wanted his people to meet for worship. They believed that it was their religious duty to convert others to Christianity. Christianity Roman Catholics believed in the Bible - both the Old Testament, By Sharon Fabian which dated back to the time before Jesus was born, and the New Testament, which contained Jesus' teachings as told by his apostles. When you look at a picture of a medieval town, what do you see at the town's center? Often, you Their beliefs led to several developments, which have become part of will see a Christian cathedral. With its tall spires the history of the Middle Ages. One was the building of magnificent reaching toward heaven, the cathedral cathedrals for worship. Another was the Crusades, military campaigns dominated the landscape in many small towns of to take back Palestine, the Christian "Holy Land," from the Muslims. the Middle Ages. This is not a surprise, since A third development was the creation of religious orders of monks Christianity was the dominant religion in Europe and nuns who made it their career to do the work of the Church. during that time. The Roman Catholic Church continued to dominate religious life in Christianity was not the only religion in Europe Europe throughout the Middle Ages, but as the Middle Ages declined, in the Middle Ages. There were Jews, Muslims, so did the power of the Church. -

Assumption Greek Orthodox Church 430 Sheep Pasture Road Port Jefferson, New York 11777

ASSUMPTION GREEK ORTHODOX CHURCH 430 SHEEP PASTURE ROAD PORT JEFFERSON, NEW YORK 11777 631-473-0894 430 SHEEP PASTURE ROAD PORT JEFFERSON, NEW YORK 11777 THE WORD "ICON" AS IT OCCURS IN THE SCRIPTURES CALL OUR OFFICE FOR DONATION TO SPONSOR THIS ICON Iconography (from Greek: εικoνογραφία) refers to the making and liturgical Saint John the Evangelist (Άγιος Ιωάννης ο Εύαγγελιστής) use of icons, pictorial representations of Biblical scenes from the life of Jesus Christ, historical events in the life of the Church, and portraits of the saints. Images have always been a vital part of the Church, but their place was the subject of the Iconoclast Controversy in the 8th and 9th centuries, especially in the East. The icons found in Orthodox Churches are a celebration of the fact that Jesus Christ is indeed the Word of God made flesh and that anyone who has seen Jesus has seen the Father (John 12:45 and 14:8-12). As the 7th Ecumenical Council held in the city of Nicea in 787 AD proclaimed, icons are in color what the Scriptures are in words: witnesses to the incarnation, the fact that God has come among us as a person whom we can see, touch and hear. In fact, in the traditional language of the Church, icons are not painted but written and an iconographer is literally "one who writes icons." "Written" or "Painted"? The most literal translation of the Greek word εικονογραφία (eikonographia) is "image writing," leading many English-speaking Orthodox Christians to insist that icons are not "painted" but rather "written." From there, further explanations are given that icons are to be understood in a manner similar to Holy Scripture—that is, they are not simply artistic compositions but rather are witnesses to the truth the way Scripture is. -

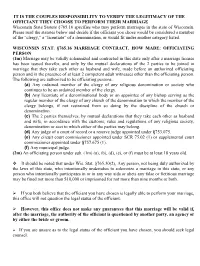

It Is the Couples Responsibility to Verify the Legitimacy Of

IT IS THE COUPLES RESPONSIBILITY TO VERIFY THE LEGITIMACY OF THE OFFICIANT THEY CHOOSE TO PERFORM THEIR MARRIAGE Wisconsin State Statute §765.16 specifies who may perform marriages in the state of Wisconsin. Please read the statutes below and decide if the officiant you chose would be considered a member of the “clergy,” a “licentiate” of a denomination, or would fit under another category listed. WISCONSIN STAT. §765.16 MARRIAGE CONTRACT, HOW MADE: OFFICIATING PERSON (1m) Marriage may be validly solemnized and contracted in this state only after a marriage license has been issued therefor, and only by the mutual declarations of the 2 parties to be joined in marriage that they take each other as husband and wife, made before an authorized officiating person and in the presence of at least 2 competent adult witnesses other than the officiating person. The following are authorized to be officiating persons: (a) Any ordained member of the clergy of any religious denomination or society who continues to be an ordained member of the clergy. (b) Any licentiate of a denominational body or an appointee of any bishop serving as the regular member of the clergy of any church of the denomination to which the member of the clergy belongs, if not restrained from so doing by the discipline of the church or denomination. (c) The 2 parties themselves, by mutual declarations that they take each other as husband and wife, in accordance with the customs, rules and regulations of any religious society, denomination or sect to which either of the parties may belong. -

Among the Religious Functions Social Is One of the Most Important One

Demuri Jalaghonia , (Georgia) PhD, Professor at Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Faculty of Humanities; Head of the Academic-Research Institute of Philosophy; Head of the Chair for Political Philosophy. GEORGIAN THEOLOGISTS ON THE INTITUTION OF MARRIAGE Among the religious functions social is one of the most important one. Religion actually influences the society, persons’ consolidations and individuals by means of belief, religious feelings and cult activities. Confessions, of course differ from each-other according to their aims and the means of implementation though each of them accomplish their specific social destination functions. Emil Durkheim points out that religion depicts not only the society structure but it supports to make it stable, religion has a uniting function as it concentrates men’s attention and inspires them with hope1. In traditional minor cultures, Durkheim proves, all the sides of life are precisely described by the religion. On the one part religious habits create new ideas and thinking categories, on the other part make the already established valuables steady. Religion is not only consecutive feelings and activities but it actually defines the rule of thinking of a man in traditional cultures2. As Michel Mill points out in spite of in what way the religious dimension will be displayed in social life we must always remember that the decrease of the religion political role do not at all mean an eradication of religious personal belief or social functions. Religious belief does not recently define functioning rules of states though it plays a vast role not only in personal but also in social lives. Very often theories of secularization meticulously define the place of religion in the present society and identify the weakening of traditional institution with the end of religion3. -

Byzantine Liturgical Hymnography: a Stumbling Stone for the Jewish-Orthodox Christian Dialogue? Alexandru Ioniță*

Byzantine Liturgical Hymnography: a Stumbling Stone for the Jewish-Orthodox Christian Dialogue? Alexandru Ioniță* This article discusses the role of Byzantine liturgical hymnography within the Jewish- Orthodox Christian dialogue. It seems that problematic anti-Jewish hymns of the Orthodox liturgy were often put forward by the Jewish side, but Orthodox theologians couldn’t offer a satisfactory answer, so that the dialogue itself profoundly suffered. The author of this study argues that liturgical hymnography cannot be a stumbling stone for the dialogue. Bringing new witnesses from several Orthodox theologians, the author underlines the need for a change of perspective. Then, beyond the intrinsic plea for the revision of the anti-Jewish texts, this article actually emphasizes the need to rediscover the Jewishness of the Byzantine liturgy and to approach the hymnography as an exegesis or even Midrash on the biblical texts and motives. As such, the anti-Jewish elements of the liturgy can be considered an impulse to a deeper analysis of Byzantine hymnography, which could be very fruitful for the Jewish-Christian Dialogue. Keywords: Jewish-Orthodox Christian Dialogue; Byzantine Hymnography; anti-Judaism; Orthodox Liturgy. Introduction The dialogue between Christian Orthodox theologians and Jewish repre- sentatives is by far one of the least documented and studied inter-religious interchanges. However, in recent years several general approaches to this topic have been issued1 and a complex study of it by Pier Giorgio Tane- burgo has even been published.2 Yet, because not all the reports presented at different Christian-Jewish joint meetings have been published and also, * Alexandru Ioniță, research fellow at the Institute for Ecumenical Research, Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu.