Alumni Edition Vii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Batman Takes Parade by Storm (Thesis by Jared Goodrich)

Jared Goodrich Batman Takes Parade By Storm (How Comic Book Culture Shaped a Small City’s Halloween parade) History Research Seminar Spring 2020 1 On Saturday, October 26th, 2019, the participants lined up to begin of the Rutland Halloween Parade. 10,000 people came to the small city of Rutland to view the famed Halloween parade for its 60th year. Over 72 floats had participated and 1700 people led by the Skelly Dancers. School floats with specific themes to the Star Wars non-profit organization the 501st Legion to droves and rows of different Batman themed floats marched throughout the city to celebrate this joyous occasion. There have been many narratives told about this historic Halloween parade. One specific example can be found on the Rutland Historical Society’s website, which is the documentary called Rutland Halloween Parade Hijinks and History by B. Burge. The standard narrative told is that on Halloween night in 1959, the Rutland area was host to its first Halloween parade, and it was a grand show in its first year. The story continues that a man by the name of Tom Fagan loved what he saw and went to his friend John Cioffredi, who was the superintendent of the Rutland Recreation Department, and offered to make the parade better the next year. When planning for the next year, Fagan suggested that Batman be a part of the parade. By Halloween of 1961, Batman was running the parade in Rutland, and this would be the start to exciting times for the Rutland Halloween parade.1 Five years into the parade, the parade was the most popular it had ever been, and by 1970 had been featured in Marvel comics Avengers Number 83, which would start a major event later in comic book history. -

Click Above for a Preview, Or Download

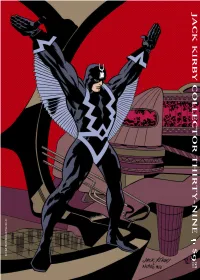

JACK KIRBY COLLECTOR THIRTY-NINE $9 95 IN THE US . c n I , s r e t c a r a h C l e v r a M 3 0 0 2 © & M T t l o B k c a l B FAN FAVORITES! THE NEW COPYRIGHTS: Angry Charlie, Batman, Ben Boxer, Big Barda, Darkseid, Dr. Fate, Green Lantern, RETROSPECTIVE . .68 Guardian, Joker, Justice League of America, Kalibak, Kamandi, Lightray, Losers, Manhunter, (the real Silver Surfer—Jack’s, that is) New Gods, Newsboy Legion, OMAC, Orion, Super Powers, Superman, True Divorce, Wonder Woman COLLECTOR COMMENTS . .78 TM & ©2003 DC Comics • 2001 characters, (some very artful letters on #37-38) Ardina, Blastaar, Bucky, Captain America, Dr. Doom, Fantastic Four (Mr. Fantastic, Human #39, FALL 2003 Collector PARTING SHOT . .80 Torch, Thing, Invisible Girl), Frightful Four (Medusa, Wizard, Sandman, Trapster), Galactus, (we’ve got a Thing for you) Gargoyle, hercules, Hulk, Ikaris, Inhumans (Black OPENING SHOT . .2 KIRBY OBSCURA . .21 Bolt, Crystal, Lockjaw, Gorgon, Medusa, Karnak, C Front cover inks: MIKE ALLRED (where the editor lists his favorite things) (Barry Forshaw has more rare Kirby stuff) Triton, Maximus), Iron Man, Leader, Loki, Machine Front cover colors: LAURA ALLRED Man, Nick Fury, Rawhide Kid, Rick Jones, o Sentinels, Sgt. Fury, Shalla Bal, Silver Surfer, Sub- UNDER THE COVERS . .3 GALLERY (GUEST EDITED!) . .22 Back cover inks: P. CRAIG RUSSELL Mariner, Thor, Two-Gun Kid, Tyrannus, Watcher, (Jerry Boyd asks nearly everyone what (congrats Chris Beneke!) Back cover colors: TOM ZIUKO Wyatt Wingfoot, X-Men (Angel, Cyclops, Beast, n their fave Kirby cover is) Iceman, Marvel Girl) TM & ©2003 Marvel Photocopies of Jack’s uninked pencils from Characters, Inc. -

Fantastic Four Compendium

MA4 6889 Advanced Game Official Accessory The FANTASTIC FOUR™ Compendium by David E. Martin All Marvel characters and the distinctive likenesses thereof The names of characters used herein are fictitious and do are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. not refer to any person living or dead. Any descriptions MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS including similarities to persons living or dead are merely co- are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. incidental. PRODUCTS OF YOUR IMAGINATION and the ©Copyright 1987 Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. All TSR logo are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. Game Design Rights Reserved. Printed in USA. PDF version 1.0, 2000. ©1987 TSR, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents Introduction . 2 A Brief History of the FANTASTIC FOUR . 2 The Fantastic Four . 3 Friends of the FF. 11 Races and Organizations . 25 Fiends and Foes . 38 Travel Guide . 76 Vehicles . 93 “From The Beginning Comes the End!” — A Fantastic Four Adventure . 96 Index. 102 This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or other unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written consent of TSR, Inc., and Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc., and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. All characters appearing in this gamebook and the distinctive likenesses thereof are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. -

The Portrayal of Women in American Superhero Comics By: Esmé Smith Junior Research Project Seminar

Hidden Heroines: The Portrayal of Women in American Superhero Comics By: Esmé Smith Junior Research Project Seminar Introduction The first comic books came out in the 1930s. Superhero comics quickly became one of the most popular genres. Today, they remain incredibly popular and influential. I have been interested in superhero comics for several years now, but one thing I often noticed was that women generally had much smaller roles than men and were also usually not as powerful. Female characters got significantly less time in the story devoted to them than men, and most superhero teams only had one woman, if they had any at all. Because there were so few female characters it was harder for me to find a way to relate to these stories and characters. If I wanted to read a comic that centered around a female hero I had to spend a lot more time looking for it than if I wanted to read about a male hero. Another thing that I noticed was that when people talk about the history of superhero comics, and the most important and influential superheroes, they almost only talk about male heroes. Wonder Woman was the only exception to this. This made me curious about other influential women in comics and their stories. Whenever I read about the history of comics I got plenty of information on how the portrayal of superheroes changed over time, but it always focused on male heroes, so I was interested in learning how women were portrayed in comics and how that has changed. -

Kirby: the Wonderthe Wonderyears Years Lee & Kirby: the Wonder Years (A.K.A

Kirby: The WonderThe WonderYears Years Lee & Kirby: The Wonder Years (a.k.a. Jack Kirby Collector #58) Written by Mark Alexander (1955-2011) Edited, designed, and proofread by John Morrow, publisher Softcover ISBN: 978-1-60549-038-0 First Printing • December 2011 • Printed in the USA The Jack Kirby Collector, Vol. 18, No. 58, Winter 2011 (hey, it’s Dec. 3 as I type this!). Published quarterly by and ©2011 TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614. 919-449-0344. John Morrow, Editor/Publisher. Four-issue subscriptions: $50 US, $65 Canada, $72 elsewhere. Editorial package ©2011 TwoMorrows Publishing, a division of TwoMorrows Inc. All characters are trademarks of their respective companies. All artwork is ©2011 Jack Kirby Estate unless otherwise noted. Editorial matter ©2011 the respective authors. ISSN 1932-6912 Visit us on the web at: www.twomorrows.com • e-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced in any manner without permission from the publisher. (above and title page) Kirby pencils from What If? #11 (Oct. 1978). (opposite) Original Kirby collage for Fantastic Four #51, page 14. Acknowledgements First and foremost, thanks to my Aunt June for buying my first Marvel comic, and for everything else. Next, big thanks to my son Nicholas for endless research. From the age of three, the kid had the good taste to request the Marvel Masterworks for bedtime stories over Mother Goose. He still holds the record as the youngest contributor to The Jack Kirby Collector (see issue #21). Shout-out to my partners in rock ’n’ roll, the incomparable Hitmen—the best band and best pals I’ve ever had. -

Read Book A-Force Vol. 1: Hypertime

A-FORCE VOL. 1: HYPERTIME PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jorge Molina,G. Willow Wilson | 144 pages | 28 Jul 2016 | Marvel Comics | 9780785196051 | English | New York, United States A-Force Vol. 1: Hypertime PDF Book Related Products. The main story is lots of fun -- Singularity comes to the newly established "normal" whatever that means at this point universe from the Battleworlds one, and is incredibly cute. Before she is brought to justice, she asks She-Hulk to tell Nico how much she loved her, and that she is going to see America again. Yay, superhero ladies! Good art, neat characters. You stay far away from this book , and Laura Martin's colours are gorgeous, especially her star-fields inside Singularity and Antimatter. This time around, the A-Force team is actually just the core members from the last volume so no one feels sidelined. Young Adult. Sort order. These are good stories; just as good is the reprint, included here, of Avengers 83, which I bought from the newsstand in October, , featuring the introduction of The Valkyrie and the Lady Liberators! Submit Review. This is a gorgeous volume of sequential art in trade paperback format. For the best experience on our site, be sure to turn on Javascript in your browser. Forgot Password. She's more than just a magic user. The artwork is gorgeous, and the story is focused on just a few of the heavy hitters. This story is a reprint of the comic A-Force Vol 2 2. With a new Thor in town it has very close ties to one of the team members, and realm-crossing dragons, Volume 2 should be a blast. -

The Phoenix/Jean Grey Across Time and Media Lenise Prater Films

Gender and Power: The Phoenix/Jean Grey across Time and Media Lenise Prater Films based on comic books have been box-office successes in recent years, particularly the X-Men franchise, which is comprised of a trilogy and two prequels,1 and the X-Men trilogy. Through the characters of Jean Grey and Rogue these films represent women as largely unable to control their powers, and subsequently as significantly dangerous to men.2 Unfortunate- ly, these problematic representations of women are often explained, or even justified, by audience members who tacitly assume, given these films are based on comics of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, that these films will feature more conservative representations of gender. Even bloggers and journalists familiar with comic books offhandedly argue that the sexism in the movies is based on the sexism in the original comics. Journalist Jeff Al- exander, for example, argues that the inclusion of strong women in comic book movies is “an uphill battle,” because “so much of the original comic- book source material is inherently sexist and objectifying to begin with.”3 Similarly, blogger Wraith24, in a discussion of promotional poster for The Avengers, concludes “that even in 2012, the influences of old sexist comics is still quite prevalent.”4 Indeed, it would not, for example, be readily ac- ceptable to name a group of men and women “X-Men” in the year 2001, as is the case with the first movie, because using “man” to describe a group that is partly comprised of women does not make sense as it did in the COLLOQUY text theory critique 24 (2012). -

Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2013 Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics Kristen Coppess Race Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Repository Citation Race, Kristen Coppess, "Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics" (2013). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 793. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/793 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BATWOMAN AND CATWOMAN: TREATMENT OF WOMEN IN DC COMICS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By KRISTEN COPPESS RACE B.A., Wright State University, 2004 M.Ed., Xavier University, 2007 2013 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Date: June 4, 2013 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Kristen Coppess Race ENTITLED Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics . BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. _____________________________ Kelli Zaytoun, Ph.D. Thesis Director _____________________________ Carol Loranger, Ph.D. Chair, Department of English Language and Literature Committee on Final Examination _____________________________ Kelli Zaytoun, Ph.D. _____________________________ Carol Mejia-LaPerle, Ph.D. _____________________________ Crystal Lake, Ph.D. _____________________________ R. William Ayres, Ph.D. -

Charles Soule Jay Leisten Steve Mcniven Sunny Gho Vc's Clayton Cowles

Thousands of years ago aliens experimented on cave men, super-charging their evolution, and then mysteriously left their experiments behind. These men and women built the City of Attilan and discovered a chemical called Terrigen that unlocked secret super powers in their modifi ed DNA, making them… MEDUSA KANG BLACK BOLT Queen Medusa took sole control over the Inhumans when her ex-husband King Black Bolt HUMAN TORCH released enormous clouds of Terrigen Mist into TRITON the atmosphere, transforming many who had no idea they were secretly Inhuman. This cost Black Bolt his throne and led him to give his and Medusa’s son Ahura into the care of the BEAST time-traveling madman Kang the Conqueror. READER A failed mission to take Ahura back has led Black Bolt back to New Attilan to seek the help of Medusa; instead he has found her in ISO the arms of her new fl ame… AHURA CHARLES STEVE JAY SUNNY VC’S CLAYTON SOULE MCNIVEN LEISTEN GHO COWLES WRITER PENCILER INKER COLORIST LETTERER STEVE McNIVEN, JAY LEISTEN, JIM CHEUNG AND JUSTIN PONSOR; CHARLES NICK AND JUSTIN PONSOR MAHMUD ASRAR AND NOLAN WOODARD BEACHAM LOWE COVER ARTISTS VARIANT COVER ARTISTS ASST. EDITOR EDITOR AXEL ALONSO JOE QUESADA DAN BUCKLEY ALAN FINE EDITOR IN CHIEF CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER PUBLISHER EXEC. PRODUCER INHUMANS CREATED BY STAN LEE & JACK KIRBY UNCANNY INHUMANS No. 2, January 2016. Published Monthly by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC. OFFICE OF PUBLICATION: 135 West 50th Street, New York, NY 10020. BULK MAIL POSTAGE PAID AT NEW YORK, NY AND AT ADDITIONAL MAILING OFFICES. -

Inhumans: Attilan Rising Free

FREE INHUMANS: ATTILAN RISING PDF Charles Soule,John Timms | 112 pages | 11 Feb 2016 | Marvel Comics | 9780785198758 | English | New York, United States Inhumans: Attilan Rising Vol 1 1 | Marvel Database | Fandom Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Inhumans: Attilan Rising for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Inhumans by Charles Soule. John Timms Illustrator. There is a rebellion brewing on Battleworld and it stretches far and wide into every domain. Medusa, ruler of Attilan, is tasked with uncovering the leader of this uprising, and scuttling it with extreme prejudice. When she discovers the leader of this rebellion is Black Bolt, however, things get complicated. Collecting : Attilan Rising Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Original Title. Other Editions 1. Friend Reviews. To see Inhumans: Attilan Rising your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To Inhumans: Attilan Rising other readers questions about Inhumansplease sign up. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 3. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Start your review of Inhumans: Attilan Rising. Dec 19, Anne rated it liked it Shelves: comicsmarvel-unlimitedgraphic-novelskindleread-in For what it was, it wasn't bad. However, part of the problem a large part with the Secret Wars tie-in stuff is that nothing that happens here will ultimately matter. And we all know it. I think I enjoyed this one as much as I did, because I looked at it strictly from a What If standpoint, and didn't try to make it anything more. -

Marvel Dice Masters: Uncanny Inhumans Monthly OP Instruction Sheet

Licensed Product: Marvel Dice Masters: Uncanny Inhumans Monthly OP Kit Release Date: Please check with your distributor for the official release date. Additional Authorized Uses (If any): In-store Organized Play events; duplication of Instruction Sheet is authorized. Marvel Dice Masters: Uncanny Inhumans Monthly OP Instruction Sheet Organized Play (OP) Kit Contents: • Twenty (20) Black Bolt: … Participation Prize Cards • Five (5) Lockjaw: LJ Limited Edition Prize Cards • Five (5) Medusa: Devoted Wife Limited Edition Prize Cards • Instruction Sheet Directions: • Schedule your Marvel Dice Masters: Uncanny Inhumans Monthly OP events in the WizKids Info Network (WIN) located at http://win.wizkids.com/. • The suggested format for Marvel Dice Masters: Uncanny Inhumans Monthly OP events is Rainbow Draft. If you’re unsure what this format is, please check www.dicemasters.com for more information and for additional formats such as constructed. • Rainbow Draft is a draft format unique to Dice Masters which allows players to use Basic Action Cards they already own along with dice from 12 foil packs of Dice Masters to build a team. Complete details on Rainbow Draft can be found at: http://dicemasters.com/rainbowdraft.pdf • Players then play a Swiss style tournament. Each round is a single game match with a 30-minute time limit plus 5 extra turns. • The Black Bolt Character Card is a Participation Prize to be awarded upon completion of the event to each player. There are 20 Cards to be handed out to players. If there are less than 20 people in the event, the Judge should be given a Black Bolt Character Card. -

Comic Books Vs. Greek Mythology: the Ultimate Crossover for the Classical Scholar Andrew S

University of Texas at Tyler Scholar Works at UT Tyler English Department Theses Literature and Languages Spring 4-30-2012 Comic Books vs. Greek Mythology: the Ultimate Crossover for the Classical Scholar Andrew S. Latham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uttyler.edu/english_grad Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Latham, Andrew S., "Comic Books vs. Greek Mythology: the Ultimate Crossover for the Classical Scholar" (2012). English Department Theses. Paper 1. http://hdl.handle.net/10950/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Literature and Languages at Scholar Works at UT Tyler. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Department Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Works at UT Tyler. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMIC BOOKS VS. GREEK MYTHOLOGY: THE ULTIMATE CROSSOVER FOR THE CLASSICAL SCHOLAR by ANDREW S. LATHAM A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Department of Literature and Languages Paul Streufert, Ph.D., Committee Chair College of Arts and Sciences The University of Texas at Tyler May 2012 Acknowledgements There are entirely too many people I have to thank for the successful completion of this thesis, and I cannot stress enough how thankful I am that these people are in my life. In no particular order, I would like to dedicate this thesis to the following people… This thesis is dedicated to my mother and father, Mark and Seba, who always believe in me, despite all evidence to the contrary.