Edited by Lisa Nandy Mp Published by Labourlist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Red Book

The For this agenda-setting collection, the leading civil society umbrella groups ACEVO and CAF worked with Lisa Nandy MP to showcase some of Red Book Labour’s key thinkers about the party’s future relationship with charities The and social enterprises. The accompanying ‘Blue Book’ and ‘Yellow Book’ feature similar essays from the Conservative and Liberal Democrat Parties. ‘This collection of essays shows the depth and vibrancy of thinking across the Labour movement on this important issue and makes a vital the Voluntary of Sector Red Book contribution to the debate in the run-up to the next election.’ Rt Hon Ed Miliband MP, Leader of the Labour Party of the ‘I hope this collection will be a provocation to further dialogue with Labour and with all the major political parties. It demonstrates a willingness to listen … that our sector should be grateful for.’ Voluntary Sector Sir Stephen Bubb, Chief Executive, ACEVO ‘The contributions in this collection show that the Labour Party possesses exciting ideas and innovations designed to strengthen Britain’s charities, Civil Society and the Labour Party and many of the concepts explored will be of interest to whichever party (or parties) are successful at the next election.’ after the 2015 election Dr John Low CBE, Chief Executive, Charities Aid Foundation With a foreword by the Rt Hon Ed Miliband MP £20 ISBN 978-1-900685-70-2 9 781900 685702 acevo-red-book-cover-centred-spine-text.indd All Pages 05/09/2014 15:40:12 The Red Book of the Voluntary Sector Civil Society and the Labour Party after -

Television Dramas Have Increasingly Reinforced a Picture of British Politics As ‘Sleazy’

Television dramas have increasingly reinforced a picture of British politics as ‘sleazy’ blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/new-labour-sleaze-and-tv-drama/ 4/22/2014 There were 24 TV dramas produced about New Labour and all made a unique contribution to public perceptions of politics. These dramas increasingly reinforced a picture of British politics as ‘sleazy’ and were apt to be believed by many already cynical viewers as representing the truth. Steven Fielding argues that political scientists need to look more closely at how culture is shaping the public’s view of party politics. On the evening of 28th February 2007, 4.5 million ITV viewers saw Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott receive a blowjob. Thankfully, they did not see the real Prescott on the screen but instead actor John Henshaw who played him in Confessions of a Diary Secretary. Moreover, the scene was executed with some discretion: shot from behind a sofa all viewers saw was the back of the Deputy Prime Minister’s head. Prescott’s two-year adulterous affair with civil servant Tracey Temple had been splashed across the tabloids the year before and ITV had seen fit to turn this private matter into a broad comedy, one which mixed known fact with dramatic invention. Confessions of a Diary Secretary is just one of twenty-four television dramas produced about New Labour which I discuss in my new article in the British Journal of Politics and International Relations. Some of these dramas were based on real events, others elliptically referenced the government and its personnel; but all made, I argue, a unique contribution to public perceptions of politics. -

National Policy Forum (NPF) Report 2018

REPORT 2018 @LabPolicyForum #NPFConsultation2018 National Policy Forum Report 2018 XX National Policy Forum Report 2018 Contents NPF Elected Officers ....................................................................................................................4 Foreword ........................................................................................................................................5 About this document ...................................................................................................................6 Policy Commission Annual Reports Early Years, Education and Skills ............................................................................................7 Economy, Business and Trade ............................................................................................. 25 Environment, Energy and Culture ....................................................................................... 39 Health and Social Care ........................................................................................................... 55 Housing, Local Government and Transport ..................................................................... 71 International ............................................................................................................................. 83 Justice and Home Affairs ....................................................................................................... 99 Work, Pensions and Equality ..............................................................................................119 -

Lisa Nandy MP, Shadow Foreign Secretary

1 ANDREW MARR SHOW, 21ST MARCH, 2021 - LISA NANDY, MP ANDREW MARR SHOW, 21ST MARCH, 2021 LISA NANDY, MP SHADOW FOREIGN SECRETARY (Please check against delivery (uncorrected copies)) AM Lisa Nandy, it’s clear that the EU threat to block vaccines coming into the UK is still live. If that happens, how should the UK respond? LN: Well, I think the President of the European Commission’s comments were deeply, deeply unhelpful. I think that it was right listening to the Commissioner just now that we should try to calm down these tensions. We’ve seen throughout this process that we do better when we work together, that if we don’t defeat the virus everywhere we’re not going to defeat it anywhere, and there are new strains of the virus that are currently emerging. The South African variant which scientists are particularly worried about that is starting to gain traction in France that we need to be very mindful of. We may not be out of the woods with Covid yet and so we’ve got to work together. That means we need to calm these tensions; blockades are really unhelpful. I would urge the European Commission to calm down the language, cool the rhetoric and let’s try and work together to get through this crisis. AM: One of the crucial components of the Pfizer vaccine is made in Cheshire. If the EU banned the export of vaccines into the UK would the UK be justified in banning the exports of components back into the EU? LN: Well look, this is precisely the tit for tat we don’t want to get into. -

Coventry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Coventry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is the national record of people who have shaped British history, worldwide, from the Romans to the 21st century. The Oxford DNB (ODNB) currently includes the life stories of over 60,000 men and women who died in or before 2017. Over 1,300 of those lives contain references to Coventry, whether of events, offices, institutions, people, places, or sources preserved there. Of these, over 160 men and women in ODNB were either born, baptized, educated, died, or buried there. Many more, of course, spent periods of their life in Coventry and left their mark on the city’s history and its built environment. This survey brings together over 300 lives in ODNB connected with Coventry, ranging over ten centuries, extracted using the advanced search ‘life event’ and ‘full text’ features on the online site (www.oxforddnb.com). The same search functions can be used to explore the biographical histories of other places in the Coventry region: Kenilworth produces references in 229 articles, including 44 key life events; Leamington, 235 and 95; and Nuneaton, 69 and 17, for example. Most public libraries across the UK subscribe to ODNB, which means that the complete dictionary can be accessed for free via a local library. Libraries also offer 'remote access' which makes it possible to log in at any time at home (or anywhere that has internet access). Elsewhere, the ODNB is available online in schools, colleges, universities, and other institutions worldwide. Early benefactors: Godgifu [Godiva] and Leofric The benefactors of Coventry before the Norman conquest, Godgifu [Godiva] (d. -

View Early Day Motions PDF File 0.12 MB

Published: Tuesday 26 January 2021 Early Day Motions tabled on Monday 25 January 2021 Early Day Motions (EDMs) are motions for which no days have been fixed. The number of signatories includes all members who have added their names in support of the Early Day Motion (EDM), including the Member in charge of the Motion. EDMs and added names are also published on the EDM database at www.parliament.uk/edm [R] Indicates that a relevant interest has been declared. New EDMs 1389 Support for British Gas workers Tabled: 25/01/21 Signatories: 1 Nadia Whittome That this House condemns the actions of British Gas in pursuing fire and re-hire tactics with loyal and hard-working staff; expresses support and solidarity with British Gas workers who have been forced to strike following British Gas pushing ahead with plans that have been rejected by 86 per cent of GMB members working as engineers; notes that the proposed changes will mean that a number of workers will be expected to work approximately 150 hours extra per year for no guarantee of extra pay; expresses regret that a once respected and trusted brand is doing damage to its reputation by pursuing fire and re-hire tactics; urges British Gas to recognise that the only way to end the disruption is to take fire and rehire pay cuts off the table; notes with alarm the growing number of employers who are making employees redundant before re-employing them on less-favourable terms and conditions; believes that these employers should instead be focused on supporting their employees through the covid-19 outbreak; and calls on the Government to take urgent action to stop the growing number of firms taking part in this unethical and unjust practice, for example by amending the Employment Rights Act 1996 to automatically categorise such redundancies as unfair dismissals. -

347 Tuesday 11 June 2013 CONSIDERATION of BILL

347 House of Commons Tuesday 11 June 2013 CONSIDERATION OF BILL CHILDREN AND FAMILIES BILL, AS AMENDED NEW CLAUSES Transfer of EHC plans Secretary Michael Gove NC9 To move the following Clause:— ‘(1) Regulations may make provision for an EHC plan maintained for a child or young person by one local authority to be transferred to another local authority in England, where the other authority becomes responsible for the child or young person. (2) The regulations may in particular— (a) impose a duty on the other authority to maintain the plan; (b) treat the plan as if originally prepared by the other authority; (c) treat things done by the transferring authority in relation to the plan as done by the other authority.’. Childcare costs scheme: preparatory expenditure Secretary Michael Gove NC10 To move the following Clause:— ‘The Commissioners for Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs may incur expenditure in preparing for the introduction of a scheme for providing assistance in respect of the costs of childcare.’. 348 Consideration of Bill: 11 June 2013 Children and Families Bill, continued Regulation of child performance Tim Loughton Meg Munn NC3 To move the following Clause:— ‘(1) In section 37 of the Children and Young Persons Act 1963 (Restriction on persons under 16 taking part in public performances, etc.) the words “under the compulsory school leaving age” shall be inserted after the word “child” in subsection (1). (2) After subsection (2) there shall be inserted— “(2A) In this section, “Performance” means the planned participation by a -

NEW SHADOW CABINET 2020 Who’S In, Who’S Out?

NEW SHADOW CABINET 2020 Who’s In, Who’s Out? BRIEFING PAPER blackcountrychamber.co.uk Who’s in and Who’s out? Sir Keir Starmer, newly elected Leader of the UK Labour Party, set about building his first Shadow Cabinet, following his election win in the Labour Party leadership contest. In our parliamentary system, a cabinet reshuffle or shuffle is an informal term for an event that occurs when the head of a government or party rotates or changes the composition of ministers in their cabinet. The Shadow Cabinet is a function of the Westminster system consisting of a senior group of opposition spokespeople. It is the Shadow Cabinet’s responsibility to scrutinise the policies and actions of the government, as well as to offer alternative policies. Position Former Post Holder Result of New Post Holder Reshuffle Leader of the Opposition The Rt Hon Jeremy Resigned The Rt Hon Sir Keir Starmer and Leader of the Labour Corbyn MP KCB QC MP Party Deputy Leader and Chair of Tom Watson Resigned Angela Raynor MP the Labour Party Shadow Chancellor of the The Rt Hon John Resigned Anneliese Dodds MP Exchequer McDonnell MP Shadow Foreign Secretary The Rt Hon Emily Moved to Lisa Nandy MP Thornberry MP International Trade Shadow Home Secretary The Rt Hon Diane Resigned Nick Thomas-Symonds MP Abbott MP Shadow Chancellor of the Rachel Reeves MP Duchy of Lancaster Shadow Justice Secretary Richard Burgon MP Left position The Rt Hon David Lammy MP Shadow Defence Secretary Nia Griffith MP Moved to Wales The Rt Hon John Healey MP Office Shadow Business, Energy Rebecca -

Westminster Hall Tuesday 13 October 2020

Issued on: 12 October at 7.05pm Call lists for Westminster Hall Tuesday 13 October 2020 A list of Members physically present to participate in Westminster Hall debates. For 60-minute and 90-minute debates, only Members who are on the call list are permitted to attend. Mem- bers are not permitted to attend only to intervene. For 30-minute debates, there will not be a call list. Members wishing to contribute should follow existing conventions about contacting the Member in charge of the debate, the Speaker’s Office and the Minister. If sittings are suspended for divisions in the House, additional time is added. Call lists are compiled and published incrementally as information becomes available. For the most up-to- date information see the parliament website: https:// commonsbusiness.parliament.uk/ 2 Call lists for Westminster Hall Tuesday 13 October 2020 CONTENTS 1. Introduction of a universal basic income 3 2. The future of the RNLI and independent life- boats after the covid-19 outbreak 4 3. Chinese and East Asian communities’ experience of racism during the covid-19 pandemic 5 Call lists for Westminster Hall Tuesday 13 October 2020 3 INTRODUCTION OF A UNIVERSAL BASIC INCOME 9.30am to 11.00am Member Party Ronnie Cowan (Inverclyde) SNP Member in charge Christine Jardine (Edinburgh West) LD Rachael Maskell (York Central) Labour Lloyd Russell-Moyle (Brighton, Labour Kemptown) Wendy Chamberlain (North East LD Fife) Jim Shannon (Strangford) DUP Chris Stephens (Glasgow South SNP SNP Spokes- West) person Ms Karen Buck (Westminster North) Labour -

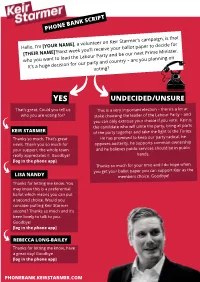

Script Flow Chart

PHONE BANK SCRIPT at ’s campaign, is th r on Keir Starmer AME], a voluntee de for ello, I’m [YOUR N llot paper to deci H ’ll receive your ba E]?Next week you e Minister. [THEIR NAM d be our next Prim e Labour Party an u want to lead th u planning on who yo d country – are yo n for our party an It’s a huge decisio voting? YES UNDECIDED/UNSURE That’s great. Could you tell us This is a very important election – there’s a lot at who you are voting for? stake choosing the leader of the Labour Party – and you can only exercise your choice if you vote. Keir is the candidate who will unite the party, bring all parts KEIR STARMER of the party together and take the fight to the Tories. cal, he Thanks so much. That’s great He has promised to keep our party radi wnership news. Thank you so much for opposes austerity, he supports common o in public your support, the whole team and he believes public services should be really appreciates it. Goodbye! hands. [log in the phone app] Thanks so much for your time and I do hope when you get your ballot paper you can support Keir as the LISA NANDY members choice. Goodbye! Thanks for letting me know. You may know this is a preferential ballot which means you can put a second choice. Would you consider putting Keir Starmer second? Thanks so much and it’s been lovely to talk to you. -

Beyond Factionalism to Unity: Labour Under Starmer

Beyond factionalism to unity: Labour under Starmer Article (Accepted Version) Martell, Luke (2020) Beyond factionalism to unity: Labour under Starmer. Renewal: A journal of social democracy, 28 (4). pp. 67-75. ISSN 0968-252X This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/95933/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk Beyond Factionalism to Unity: Labour under Starmer Luke Martell Accepted version. Final article published in Renewal 28, 4, 2020. The Labour leader has so far pursued a deliberately ambiguous approach to both party management and policy formation. -

Labour Loses out to Lara As Britain's Youth Fails to Spot the Cabinet

Labour Loses out to Lara as Britain's Youth Fails to Spot the Cabinet August 1, 2000 It 's Pokemon vs. the Politicians! 1 August 2000, London: Video games characters are more recognisable to Britain's youth than the country's most powerful politicians, including Tony Blair. That is the shock result of a new survey of 16-21 year olds released today by Amazon.co.uk, Britain's leading online retailer, which commissioned the research as part of the launch of its new PC and Video Games store. When asked to identify photographs, 96% correctly named Super Mario and 93% the Pokemon character Pikachu, whereas the Prime Minister was correctly identified by only 91%. Lara Croft, pin-up heroine of the Tomb Raider games, was identified by 80% of respondents. However, Tony Blair has a far higher profile than his cabinet colleagues. Less than one in four (24%) of 16-21 year olds recognised Chancellor of the Exchequer Gordon Brown, Home Secretary Jack Straw was correctly identified by just 33%, and Foreign Secretary Robin Cook by 42%. Other members of the cabinet fared even less well - Mo Mowlam was correctly identified by only 37% of respondents and Peter Mandelson by a meagre 18%, despite their recent high media profile. Donkey Kong, the gorilla hero of video games since the 1980s, was the least recognisable video games character at 67%, but still polled 25% higher than any cabinet member except for the Prime Minister himself. When asked how important a role the politicians and video games characters played in their lives, despite the politicians polling higher than the video games characters, nearly one in three (29%) said that Tony Blair was either not very important or not all important to their lives.