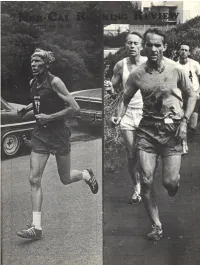

Just Joe Joe Henderson’S Career Has Helped Define the Sport

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Event Winners

Meet History -- NCAA Division I Outdoor Championships Event Winners as of 6/17/2017 4:40:39 PM Men's 100m/100yd Dash 100 Meters 100 Meters 1992 Olapade ADENIKEN SR 22y 292d 10.09 (2.0) +0.09 2017 Christian COLEMAN JR 21y 95.7653 10.04 (-2.1) +0.08 UTEP {3} Austin, Texas Tennessee {6} Eugene, Ore. 1991 Frank FREDERICKS SR 23y 243d 10.03w (5.3) +0.00 2016 Jarrion LAWSON SR 22y 36.7652 10.22 (-2.3) +0.01 BYU Eugene, Ore. Arkansas Eugene, Ore. 1990 Leroy BURRELL SR 23y 102d 9.94w (2.2) +0.25 2015 Andre DE GRASSE JR 20y 215d 9.75w (2.7) +0.13 Houston {4} Durham, N.C. Southern California {8} Eugene, Ore. 1989 Raymond STEWART** SR 24y 78d 9.97w (2.4) +0.12 2014 Trayvon BROMELL FR 18y 339d 9.97 (1.8) +0.05 TCU {2} Provo, Utah Baylor WJR, AJR Eugene, Ore. 1988 Joe DELOACH JR 20y 366d 10.03 (0.4) +0.07 2013 Charles SILMON SR 21y 339d 9.89w (3.2) +0.02 Houston {3} Eugene, Ore. TCU {3} Eugene, Ore. 1987 Raymond STEWART SO 22y 80d 10.14 (0.8) +0.07 2012 Andrew RILEY SR 23y 276d 10.28 (-2.3) +0.00 TCU Baton Rouge, La. Illinois {5} Des Moines, Iowa 1986 Lee MCRAE SO 20y 136d 10.11 (1.4) +0.03 2011 Ngoni MAKUSHA SR 24y 92d 9.89 (1.3) +0.08 Pittsburgh Indianapolis, Ind. Florida State {3} Des Moines, Iowa 1985 Terry SCOTT JR 20y 344d 10.02w (2.9) +0.02 2010 Jeff DEMPS SO 20y 155d 9.96w (2.5) +0.13 Tennessee {3} Austin, Texas Florida {2} Eugene, Ore. -

Ebook Duel in the Sun: Alberto Salazar, Dick Beardsley, And

Ebook Duel In The Sun: Alberto Salazar, Dick Beardsley, And America's Greatest Marathon Freeware The 1982 Boston Marathon was great theater: Two American runners, Alberto Salazar, a celebrated champion, and Dick Beardsley, a gutsy underdog, going at each other for just under 2 hours and 9 minutes. Neither man broke. The race merely came to a thrilling, shattering end, exacting such an enormous toll that neither man ever ran as well again. Beardsley, the most innocent of men, descended into felony drug addiction, and Salazar, the toughest of men, fell prey to depression. Exquisitely written and rich with human drama, John Brant's Duel in the Sun brilliantly captures the mythic character of the most thrilling American marathon ever run―and the powerful forces of fate that drove these two athletes in the years afterward. Paperback: 256 pages Publisher: Rodale Books (March 6, 2007) Language: English ISBN-10: 1594866287 ISBN-13: 978-1594866289 Product Dimensions: 6.1 x 0.4 inches Shipping Weight: 9.6 ounces (View shipping rates and policies) Average Customer Review: 4.3 out of 5 stars 65 customer reviews Best Sellers Rank: #222,752 in Books (See Top 100 in Books) #80 in Books > Sports & Outdoors > Other Team Sports > Track & Field #344 in Books > Sports & Outdoors > Miscellaneous > History of Sports #370 in Books > Health, Fitness & Dieting > Exercise & Fitness > Running & Jogging In 1982, Alberto Salazar and Dick Beardsley ran the entire 26.2 miles of the Boston Marathon neck and neck, finishing within two seconds of each other. For both, it was the pinnacle of a running career cut short, for Salazar because of a mysterious malaise, and for Beardsley because of a drug addiction that developed after a farm accident. -

This Entire Document

THE TURKEY SAYS: HAVE WE GOT A CHRISTMAS PACKAGE FOR YOU! With the holiday season fast approaching, it is that time of the year to start thinking about Christmas gifts. The Athletic Department would like to help you out by offering a package deal of running shoes and warm-up suits. For $39.99 you can get the NIKE nylon cortez (regular $24.95) and a 100% nylon Add-In Warm- Up Suit (regular $24.95). A savings of $9.91. A nice gift might be a 100% cot ton Rugby Shirt: -- Long Sleeve $14.95 or Short Sleeve $12.95. Remember, we have gift certificates tool STORE HOURS: Mon-Fri (10-6); Sat (10-5) the athletic department 2114 ADDISON STREET, BERKELEY, CA 94704 — PH. (415) 843-7767 CALIFORNIA TRACE NEWS A PUBLICATION DEVOTED TO CALIFORNIA TRACK PUBLISHED BIMONTHLY MASTERS GIRLS--WOMEN RESULTS PICTURES RANKINGS PROFILES SCHEDULES MORE 12 WEST 25th AVE. HOURS: M-TH (10-7) SAN MATEO, CA. 94403 FRI (10-8) PH. (415) 349-6904 SAT (10-6) ON THE COVEN Two National A.A.U. Masters Champions: (Left) Jim Shettler (WVJS) grabbed the 25 Kilo in 1:27:48 at Golden Gate Park, San Francisco. /Dermis O'Rorke/ (Right) Ray Menzie (WVTC) annexed the marathon title with a sparkling 2:36:40 in Ore gon. Menzie then led an all-star PA Masters team to victory at the Masters X-Country Championships in New York in mid-November. /Jim Engle/ Staff & Rates CONTENTS EDITOR: Jack Leydig ADVERTISING: Bill Clark THIS & THAT 3 SPECIAL ARTICLE 13 PUBLISHER: Frank Cunningham RESULTS: Penny DeMoss LONG DISTANCE RATINGS 5 MEDICAL ADVICE COLUMN 14 MEDICAL ADVICE: Harry Hlavac, DPM CIRCULATION: David Shrock CLUB NEWS 6 NUTRITION CORNER 15 ARTIST: Penny DeMoss PHOTO EDITOR: John Marconi CLASSIFIED ADS 7 SCHEDULING 18 CARTOONIST: David Brown PROD. -

December 1980 $1.00

National 'Masters Newsletter . 28th Issue December 1980 $1.00 The only national publication devoted exclusively to track & field and long distance running for men and women over age 30 KeUey Steals Show * Highlights *- Robinson, Rapp, Win Second Brooks • Results of: Master Run National 10K Brooks 15K WASHINGTON, D.C., October 19. National 10K XC The top. American master runners New York Marathon probably will be happy to see -Roger Masters Sports X-C Robinson (visiting the United States on Diet-Pepsi Nationals a six-week lecture tour) return to New Zealand. They will'not need to face him Eastern X-C again for at least several months and Throw-a-thon then only if they travel to his country Pentathlons for the World Veteran Games. • New Marks set Robinson, an English professor who by: lectures abou,t Shakespeare, among Higdon, O'Neil, Chisholm, other subjects, had taken the measure Sipprelle, Dick,d'Elia, of the best masters the Midwest had to Bowers, McKenzie offer two weeks ~arlier in Chesterton, Indiana in the first Brooks Master Run. • e Mu ual, Nike to hold On this Sunday he dispatched the East Series of Masters Races Coast's best in the -second such affair, running 47:23 for 15 kilometers over a -- National 10K X-C scenic but bumpy course along the C&O Canal towpath in Washington, D.C. But Robinson was not the only star performer in the second Brooks Master Run held urider mostly overcast skies and with temperatures around 60 de Bowers Breaks grees. Main speaker at the Saturday night banquet at the Rosslyn Westpark Marathon Mark Roger Robinson, 41, of New Zealand, one of the top masters distance runners In Hotel was John A. -

From Whence We Came

From Whence We Came _________________________________________________________________________________________ The marathon took its inspiration from one of the greatest athletic feats in history. And the Christchurch Airport Marathon took its inspiration from one of the greatest marathons in history. ________________________________________________________________________________________ Marathon running, as we know it, hails back to Athens ______________________________________________ in 1896 and the first modern Olympiad. But the The first “City of Christchurch International Marathon” inspiration for this most classic of challenges hails back to a mythical Greek messenger named Pheidippides. Depending on which of history’s great bards you believe, Pheidippides ran 24 miles between Marathon and Athens to announce an Athenian victory in the Battle of Marathon. Upon delivering the message he dropped down dead, and so was born the great nobility of long distance running and the challenge they eventually dubbed “the marathon.” It was that great tale that inspired the first Olympic marathon and a quarter of a century later a similarly inspiring race took place right here in Christchurch. Like the marathon itself, the Christchurch Marathon ______________________________________________ was inspired by one of the greatest races in history; n With so many world class runners in the marathon field the 1974 Christchurch Commonwealth Games, on the the pace was always going to be fast. After looking same basic route that our race used until the 2010 over the flat course and fast line-up Derek Clayton said earthquakes, Great Britain’s Ian Thompson ran what he wouldn’t be surprised if the world record was was then the second fastest marathon of all time. broken. With Hill and Clayton both merciless front- runners the early pace did indeed go out at world It was one of history’s greatest marathon races. -

Updated 2019 Completemedia

April 15, 2019 Dear Members of the Media, On behalf of the Boston Athletic Association, principal sponsor John Hancock, and all of our sponsors and supporters, we welcome you to the City of Boston and the 123rd running of the Boston Marathon. As the oldest annually contested marathon in the world, the Boston Marathon represents more than a 26.2-mile footrace. The roads from Hopkinton to Boston have served as a beacon for well over a century, bringing those from all backgrounds together to celebrate the pursuit of athletic excellence. From our early beginnings in 1897 through this year’s 123rd running, the Boston Marathon has been an annual tradition that is on full display every April near and far. We hope that all will be able to savor the spirit of the Boston Marathon, regardless whether you are an athlete or volunteer, spectator or member of the media. Race week will surely not disappoint. The race towards Boylston Street will continue to showcase some of the world’s best athletes. Fronting the charge on Marathon Monday will be a quartet of defending champions who persevered through some of the harshest weather conditions in race history twelve months ago. Desiree Linden, the determined and resilient American who snapped a 33-year USA winless streak in the women’s open division, returns with hopes of keeping her crown. Linden has said that last year’s race was the culmination of more than a decade of trying to tame the beast of Boston – a race course that rewards those who are both patient and daring. -

The History of the Pan American Games

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1964 The iH story of the Pan American Games. Curtis Ray Emery Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Emery, Curtis Ray, "The iH story of the Pan American Games." (1964). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 977. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/977 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been 65—3376 microfilmed exactly as received EMERY, Curtis Ray, 1917- THE HISTORY OF THE PAN AMERICAN GAMES. Louisiana State University, Ed.D., 1964 Education, physical University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE HISTORY OF THE PAN AMERICAN GAMES A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education m The Department of Health, Physical, and Recreation Education by Curtis Ray Emery B. S. , Kansas State Teachers College, 1947 M. S ., Louisiana State University, 1948 M. Ed. , University of Arkansas, 1962 August, 1964 PLEASE NOTE: Illustrations are not original copy. These pages tend to "curl". Filmed in the best possible way. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS, INC. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study could not have been completed without the close co operation and assistance of many individuals who gave freely of their time. -

PRESS RELEASE 2017 Napa Valley Marathon

From: Mark Winitz Subject: PRESS RELEASE: 2017 Napa Valley Marathon Announces Elite Field Date: February 24, 2017 at 2:32 PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release Contact: Mark Winitz (email) Win-It!z Sports Public Relations Tel: (650) 948-0618 THREE-TIME NAPA VALLEY MARATHON CHAMPION CHRIS MOCKO HIGHLIGHTS 2017 ELITE FIELD 39th Annual Race Will Also Honor Past Standout Dick Beardsley NAPA, Calif. — February 24, 2017 —The Kaiser Permanente Napa Valley Marathon (NVM) announced today that three-time men’s champion Chris Mocko (Mill Valley, Calif.) will return to world-renowned Napa Valley and anchor a small, but talented, elite field on Sunday, March 5, 2017. Mocko, age 30, has competed five previous times on the race’s fast point-to-point 26.2-mile course. He won NVM in 2011, 2012, and 2015 and placed second in 2014. In 2013 he placed 10th. Only one athlete to date has won NVM four times: Mary Coordt (Elk Grove, Calif.) who ran away with women’s victories in 1997, 2005, 2009, and 2010. Today, Coordt serves as NVM’s Elite Athlete Recruiter and Coordinator. “The Napa Valley Marathon is near and dear to me,” Mocko said. “I can’t think of a better combination of a challenging, but fast, course. The race offers beautiful scenery, great event organization, and the best prize for winners under the sun. And, the timing of the race has always fit well into my training schedule.” NVM rewards the male and female overall winners with their weight in premium Napa Valley wine. Open and masters winners also win specially etched bottles of Napa Valley wine as trophies to commemorate their status as Road Runners Club of America Western Regional Marathon champions. -

Formation of the Sport of Athletics in Rotorua

Lake City Athletic Club Inc A History by Pam Kenny Three clubs joined together in April 1991, to form the current Lake City Athletic Club Inc. A short history of the earlier clubs is shown first. Rotorua Amateur Athletic & Cycling Club / Rotorua Athletic Club 1931-1991 On the 13 November 1931 a meeting was convened at Brent’s Bathgate House to establish an athletic and cycling club in Rotorua. Thirty people were in attendance and the Rotorua Amateur Athletic and Cycling Club was formed, with the club achieving incorporated society status in 1938. Blue and gold were the club colours - blue singlet/blouse and shorts with gold “R” on the top. Weekly competitions were held at the Rotorua Boys High on a Friday evening, with the customary track and field events for the runners, with cyclists contesting both track and road races. Val Robinson winning an early ladies’ athletics meeting in the late 1940's The club went into recess during the Second World War, with activities resuming October 1944. Venues utilized between 1944 and 1960 were Harriers in the late 1940's - L to R; John Wild, Alex Kuirau Park, the old A&P Showgrounds near Uta Millar, Keith French, Harry Findon Street, Arawa Park, Pererika Street, and again Kuirau Park. 1961 saw the Club at Smallbone Park, its home until the 1983/84 season, when a move was made to the new International Stadium, though the inadequacy of the track led to a return to Smallbone Park for a season. 1986 it was back to the Stadium until sand carpeting of the ground prevented permanent lane markings and children being able to run barefooted. -

October 1982

m ^HtGHLIGHTS^ •RESULTS OF 11 TRACK & FIELD MEETS •RESULTS OF 42 DISTANCE RUNS -World Decathlon -No. California •America's Finest City -Nike Marathon -Pan-American -Empire State -Midwest Masters 25K -San Francisco Marathon -Rocky Mountain .gt Louis -Nike Grand Prix lOK -World Veterans Marathon & lOK ;Europea„Championships -Pikes Peak Marathon -And 28 More -Indiana -Columbus -7 Pepsi Challenges • 1981 HALF-MARATHON RANKINGS ^ National Masters News "5 Theonlynationalpublication devoted exclusively to track &field and longdistance running for menand women over age 30 50th Issue October, 1982 $1.25 Binder Sets Mark in Nike Marathon RECORDS FALL 2:13:41 For Villanueva AT FIRST WAVA EUGENE, Oregon, Sept. 12. Mex-' DECATHLON ico's 42-year-old running sensation Antonio Villanueva became the second by ED OLEATA fastest veteran marathoner in history Never mind that the meet was billed as today by blazing to a 2:13:41 in the . a world championship and only two Nike/Oregon Track Club marathon. foreigners showed up (five others were His stunning effort is surpassed only entered), the first World Veteran by New Zealander Jack Foster's Decathlon Championship held in San 2:ll:19 on the all-time over-age-40 Diego on August 28th and 29th was charts. simply the best masters decathlon meet ever held. Eleven new decathlon world Just three weeks ago, Villanueva had records were set for total points and set a world veterans half-marathon world records were set in at least two record of 1:05:20 in San Diego. His individual events. performance today moved Runner's World's Marty Post to describe A number ofAmerican athletes skip Villanueva as "probably the top ped the USA championships and masters runner in the woiid light pointed for this meet. -

USATF Cross Country Championships Media Handbook

TABLE OF CONTENTS NATIONAL CHAMPIONS LIST..................................................................................................................... 2 NCAA DIVISION I CHAMPIONS LIST .......................................................................................................... 7 U.S. INTERNATIONAL CROSS COUNTRY TRIALS ........................................................................................ 9 HISTORY OF INTERNATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS ........................................................................................ 20 APPENDIX A – 2009 USATF CROSS COUNTRY CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS ............................................... 62 APPENDIX B –2009 USATF CLUB NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS .................................................. 70 USATF MISSION STATEMENT The mission of USATF is to foster sustained competitive excellence, interest, and participation in the sports of track & field, long distance running, and race walking CREDITS The 30th annual U.S. Cross Country Handbook is an official publication of USA Track & Field. ©2011 USA Track & Field, 132 E. Washington St., Suite 800, Indianapolis, IN 46204 317-261-0500; www.usatf.org 2011 U.S. Cross Country Handbook • 1 HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS USA Track & Field MEN: Year Champion Team Champion-score 1954 Gordon McKenzie New York AC-45 1890 William Day Prospect Harriers-41 1955 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-28 1891 M. Kennedy Prospect Harriers-21 1956 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-46 1892 Edward Carter Suburban Harriers-41 1957 John Macy New York AC-45 1893-96 Not Contested 1958 John Macy New York AC-28 1897 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-31 1959 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-30 1898 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-42 1960 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-33 1899-1900 Not Contested 1961 Bruce Kidd Houston TFC-35 1901 Jerry Pierce Pastime AC-20 1962 Pete McArdle Los Angeles TC-40 1902 Not Contested 1963 Bruce Kidd Los Angeles TC-47 1903 John Joyce New York AC-21 1964 Dave Ellis Los Angeles TC-29 1904 Not Contested 1965 Ron Larrieu Toronto Olympic Club-40 1905 W.J. -

March/April 2019 43 Years of Running Vol

March/April 2019 43 Years of Running Vol. 45 No. 2 www.jtcrunning.com ISSUE #433 NEWSLETTER TRACK SEASON BEGINS The Starting Line LETTER FROM THE EDITOR JTC Running’s gala event of the year, the Gate River picked off by Jay, Rodney and anyone else who was in Run, is now behind us, and what a race it was. It couldn’t the mood. I think Jay must have been the person who have gone any smoother and the weather could hardly coined the famous phrase “even pace wins the race.” Jay have been finer. I shouldn’t really call it just a race for was a human metronome. it is far more than that. Even the word event seems Curiously, when Rodney and I jogged we left Jay behind, inadequate. It is a massive gathering, a party, an expo, but every time we took walking “breaks” we found Jay a celebration and, oh yes, five quite different races. way out in front of us disappearing into the crowd. Jay’s Accolades and thanks must go to race director, Doug walking pace seemed faster than his running speed and Alred, and his efficient staff. Jane Alred organized a we couldn’t keep up. I suggested a new athletic career for perfect expo, as usual. Jay in race walking. He could do it. Now in his 70s, he We must never forget all our wonderful volunteers who still runs 50 miles a week. I was astonished, even if he made the GRR what it was. They do so year after year did add: “Some of it is walking.” The man is unstoppable.