Group Lab: Configuring and Compiling the Linux Kernel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

At—At, Batch—Execute Commands at a Later Time

at—at, batch—execute commands at a later time at [–csm] [–f script] [–qqueue] time [date] [+ increment] at –l [ job...] at –r job... batch at and batch read commands from standard input to be executed at a later time. at allows you to specify when the commands should be executed, while jobs queued with batch will execute when system load level permits. Executes commands read from stdin or a file at some later time. Unless redirected, the output is mailed to the user. Example A.1 1 at 6:30am Dec 12 < program 2 at noon tomorrow < program 3 at 1945 pm August 9 < program 4 at now + 3 hours < program 5 at 8:30am Jan 4 < program 6 at -r 83883555320.a EXPLANATION 1. At 6:30 in the morning on December 12th, start the job. 2. At noon tomorrow start the job. 3. At 7:45 in the evening on August 9th, start the job. 4. In three hours start the job. 5. At 8:30 in the morning of January 4th, start the job. 6. Removes previously scheduled job 83883555320.a. awk—pattern scanning and processing language awk [ –fprogram–file ] [ –Fc ] [ prog ] [ parameters ] [ filename...] awk scans each input filename for lines that match any of a set of patterns specified in prog. Example A.2 1 awk '{print $1, $2}' file 2 awk '/John/{print $3, $4}' file 3 awk -F: '{print $3}' /etc/passwd 4 date | awk '{print $6}' EXPLANATION 1. Prints the first two fields of file where fields are separated by whitespace. 2. Prints fields 3 and 4 if the pattern John is found. -

DC Console Using DC Console Application Design Software

DC Console Using DC Console Application Design Software DC Console is easy-to-use, application design software developed specifically to work in conjunction with AML’s DC Suite. Create. Distribute. Collect. Every LDX10 handheld computer comes with DC Suite, which includes seven (7) pre-developed applications for common data collection tasks. Now LDX10 users can use DC Console to modify these applications, or create their own from scratch. AML 800.648.4452 Made in USA www.amltd.com Introduction This document briefly covers how to use DC Console and the features and settings. Be sure to read this document in its entirety before attempting to use AML’s DC Console with a DC Suite compatible device. What is the difference between an “App” and a “Suite”? “Apps” are single applications running on the device used to collect and store data. In most cases, multiple apps would be utilized to handle various operations. For example, the ‘Item_Quantity’ app is one of the most widely used apps and the most direct means to take a basic inventory count, it produces a data file showing what items are in stock, the relative quantities, and requires minimal input from the mobile worker(s). Other operations will require additional input, for example, if you also need to know the specific location for each item in inventory, the ‘Item_Lot_Quantity’ app would be a better fit. Apps can be used in a variety of ways and provide the LDX10 the flexibility to handle virtually any data collection operation. “Suite” files are simply collections of individual apps. Suite files allow you to easily manage and edit multiple apps from within a single ‘store-house’ file and provide an effortless means for device deployment. -

The Ifplatform Package

The ifplatform package Original code by Johannes Große Package by Will Robertson http://github.com/wspr/ifplatform v0.4a∗ 2017/10/13 1 Main features and usage This package provides the three following conditionals to test which operating system is being used to run TEX: \ifwindows \iflinux \ifmacosx \ifcygwin If you only wish to detect \ifwindows, then it does not matter how you load this package. Note then that use of (Linux or Mac OS X or Cygwin) can then be detected with \ifwindows\else. If you also wish to determine the difference between which Unix-variant you are using (i.e., also detect \iflinux, \ifmacosx, and \ifcygwin) then shell escape must be enabled. This is achieved by using the -shell-escape command line option when executing LATEX. If shell escape is not enabled, \iflinux, \ifmacosx, and \ifcygwin will all return false. A warning will be printed in the console output to remind you in this case. ∗Thanks to Ken Brown, Joseph Wright, Zebb Prime, and others for testing this package. 1 2 Auxiliary features \ifshellescape is provided as a conditional to test whether shell escape is active or not. (Note: new versions of pdfTEX allow you to query shell escape with \ifnum\pdfshellescape>0 , and the pdftexcmds package provides the wrapper \pdf@shellescape which works with X TE EX, pdfTEX, and LuaTEX.) Also, the \platformname command is defined to expand to a macro that represents the operating system. Default definitions are (respectively): \windowsname ! ‘Windows’ \notwindowsname ! ‘*NIX’ (when shell escape is disabled) \linuxname ! ‘Linux’ \macosxname ! ‘Mac OS X’ \cygwinname ! ‘Cygwin’ \unknownplatform ! whatever is returned by uname E.g., if \ifwindows is true then \platformname expands to \windowsname, which expands to ‘Windows’. -

Unix/Linux Command Reference

Unix/Linux Command Reference .com File Commands System Info ls – directory listing date – show the current date and time ls -al – formatted listing with hidden files cal – show this month's calendar cd dir - change directory to dir uptime – show current uptime cd – change to home w – display who is online pwd – show current directory whoami – who you are logged in as mkdir dir – create a directory dir finger user – display information about user rm file – delete file uname -a – show kernel information rm -r dir – delete directory dir cat /proc/cpuinfo – cpu information rm -f file – force remove file cat /proc/meminfo – memory information rm -rf dir – force remove directory dir * man command – show the manual for command cp file1 file2 – copy file1 to file2 df – show disk usage cp -r dir1 dir2 – copy dir1 to dir2; create dir2 if it du – show directory space usage doesn't exist free – show memory and swap usage mv file1 file2 – rename or move file1 to file2 whereis app – show possible locations of app if file2 is an existing directory, moves file1 into which app – show which app will be run by default directory file2 ln -s file link – create symbolic link link to file Compression touch file – create or update file tar cf file.tar files – create a tar named cat > file – places standard input into file file.tar containing files more file – output the contents of file tar xf file.tar – extract the files from file.tar head file – output the first 10 lines of file tar czf file.tar.gz files – create a tar with tail file – output the last 10 lines -

A First Course to Openfoam

Basic Shell Scripting Slides from Wei Feinstein HPC User Services LSU HPC & LON [email protected] September 2018 Outline • Introduction to Linux Shell • Shell Scripting Basics • Variables/Special Characters • Arithmetic Operations • Arrays • Beyond Basic Shell Scripting – Flow Control – Functions • Advanced Text Processing Commands (grep, sed, awk) Basic Shell Scripting 2 Linux System Architecture Basic Shell Scripting 3 Linux Shell What is a Shell ▪ An application running on top of the kernel and provides a command line interface to the system ▪ Process user’s commands, gather input from user and execute programs ▪ Types of shell with varied features o sh o csh o ksh o bash o tcsh Basic Shell Scripting 4 Shell Comparison Software sh csh ksh bash tcsh Programming language y y y y y Shell variables y y y y y Command alias n y y y y Command history n y y y y Filename autocompletion n y* y* y y Command line editing n n y* y y Job control n y y y y *: not by default http://www.cis.rit.edu/class/simg211/unixintro/Shell.html Basic Shell Scripting 5 What can you do with a shell? ▪ Check the current shell ▪ echo $SHELL ▪ List available shells on the system ▪ cat /etc/shells ▪ Change to another shell ▪ csh ▪ Date ▪ date ▪ wget: get online files ▪ wget https://ftp.gnu.org/gnu/gcc/gcc-7.1.0/gcc-7.1.0.tar.gz ▪ Compile and run applications ▪ gcc hello.c –o hello ▪ ./hello ▪ What we need to learn today? o Automation of an entire script of commands! o Use the shell script to run jobs – Write job scripts Basic Shell Scripting 6 Shell Scripting ▪ Script: a program written for a software environment to automate execution of tasks ▪ A series of shell commands put together in a file ▪ When the script is executed, those commands will be executed one line at a time automatically ▪ Shell script is interpreted, not compiled. -

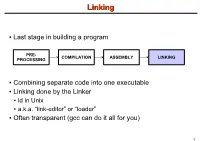

Linking + Libraries

LinkingLinking ● Last stage in building a program PRE- COMPILATION ASSEMBLY LINKING PROCESSING ● Combining separate code into one executable ● Linking done by the Linker ● ld in Unix ● a.k.a. “link-editor” or “loader” ● Often transparent (gcc can do it all for you) 1 LinkingLinking involves...involves... ● Combining several object modules (the .o files corresponding to .c files) into one file ● Resolving external references to variables and functions ● Producing an executable file (if no errors) file1.c file1.o file2.c gcc file2.o Linker Executable fileN.c fileN.o Header files External references 2 LinkingLinking withwith ExternalExternal ReferencesReferences file1.c file2.c int count; #include <stdio.h> void display(void); Compiler extern int count; int main(void) void display(void) { file1.o file2.o { count = 10; with placeholders printf(“%d”,count); display(); } return 0; Linker } ● file1.o has placeholder for display() ● file2.o has placeholder for count ● object modules are relocatable ● addresses are relative offsets from top of file 3 LibrariesLibraries ● Definition: ● a file containing functions that can be referenced externally by a C program ● Purpose: ● easy access to functions used repeatedly ● promote code modularity and re-use ● reduce source and executable file size 4 LibrariesLibraries ● Static (Archive) ● libname.a on Unix; name.lib on DOS/Windows ● Only modules with referenced code linked when compiling ● unlike .o files ● Linker copies function from library into executable file ● Update to library requires recompiling program 5 LibrariesLibraries ● Dynamic (Shared Object or Dynamic Link Library) ● libname.so on Unix; name.dll on DOS/Windows ● Referenced code not copied into executable ● Loaded in memory at run time ● Smaller executable size ● Can update library without recompiling program ● Drawback: slightly slower program startup 6 LibrariesLibraries ● Linking a static library libpepsi.a /* crave source file */ … gcc .. -

Unix/Linux Command Reference

Unix/Linux Command Reference .com File Commands System Info ls – directory listing date – show the current date and time ls -al – formatted listing with hidden files cal – show this month's calendar cd dir - change directory to dir uptime – show current uptime cd – change to home w – display who is online pwd – show current directory whoami – who you are logged in as mkdir dir – create a directory dir finger user – display information about user rm file – delete file uname -a – show kernel information rm -r dir – delete directory dir cat /proc/cpuinfo – cpu information rm -f file – force remove file cat /proc/meminfo – memory information rm -rf dir – force remove directory dir * man command – show the manual for command cp file1 file2 – copy file1 to file2 df – show disk usage cp -r dir1 dir2 – copy dir1 to dir2; create dir2 if it du – show directory space usage doesn't exist free – show memory and swap usage mv file1 file2 – rename or move file1 to file2 whereis app – show possible locations of app if file2 is an existing directory, moves file1 into which app – show which app will be run by default directory file2 ln -s file link – create symbolic link link to file Compression touch file – create or update file tar cf file.tar files – create a tar named cat > file – places standard input into file file.tar containing files more file – output the contents of file tar xf file.tar – extract the files from file.tar head file – output the first 10 lines of file tar czf file.tar.gz files – create a tar with tail file – output the last 10 lines -

“Log” File in Stata

Updated July 2018 Creating a “Log” File in Stata This set of notes describes how to create a log file within the computer program Stata. It assumes that you have set Stata up on your computer (see the “Getting Started with Stata” handout), and that you have read in the set of data that you want to analyze (see the “Reading in Stata Format (.dta) Data Files” handout). A log file records all your Stata commands and output in a given session, with the exception of graphs. It is usually wise to retain a copy of the work that you’ve done on a given project, to refer to while you are writing up your findings, or later on when you are revising a paper. A log file is a separate file that has either a “.log” or “.smcl” extension. Saving the log as a .smcl file (“Stata Markup and Control Language file”) keeps the formatting from the Results window. It is recommended to save the log as a .log file. Although saving it as a .log file removes the formatting and saves the output in plain text format, it can be opened in most text editing programs. A .smcl file can only be opened in Stata. To create a log file: You may create a log file by typing log using ”filepath & filename” in the Stata Command box. On a PC: If one wanted to save a log file (.log) for a set of analyses on hard disk C:, in the folder “LOGS”, one would type log using "C:\LOGS\analysis_log.log" On a Mac: If one wanted to save a log file (.log) for a set of analyses in user1’s folder on the hard drive, in the folder “logs”, one would type log using "/Users/user1/logs/analysis_log.log" If you would like to replace an existing log file with a newer version add “replace” after the file name (Note: PC file path) log using "C:\LOGS\analysis_log.log", replace Alternately, you can use the menu: click on File, then on Log, then on Begin. -

21Files2.Pdf

Here is a portion of a Unix directory tree. The ovals represent files, the rectangles represent directories (which are really just special cases of files). A simple implementation of a directory consists of an array of pairs of component name and inode number, where the latter identifies the target file’s inode to the operating system (an inode is data structure maintained by the operating system that represents a file). Note that every directory contains two special entries, “.” and “..”. The former refers to the directory itself, the latter to the directory’s parent (in the case of the slide, the directory is the root directory and has no parent, thus its “..” entry is a special case that refers to the directory itself). While this implementation of a directory was used in early file systems for Unix, it suffers from a number of practical problems (for example, it doesn’t scale well for large directories). It provides a good model for the semantics of directory operations, but directory implementations on modern systems are more complicated than this (and are beyond the scope of this course). Here are two directory entries referring to the same file. This is done, via the shell, through the ln command which creates a (hard) link to its first argument, giving it the name specified by its second argument. The shell’s “ln” command is implemented using the link system call. Here are the (abbreviated) contents of both the root (/) and /etc directories, showing how /unix and /etc/image are the same file. Note that if the directory entry /unix is deleted (via the shell’s “rm” command), the file (represented by inode 117) continues to exist, since there is still a directory entry referring to it. -

The AWK Programming Language

The Programming ~" ·. Language PolyAWK- The Toolbox Language· Auru:o V. AHo BRIAN W.I<ERNIGHAN PETER J. WEINBERGER TheAWK4 Programming~ Language TheAWI(. Programming~ Language ALFRED V. AHo BRIAN w. KERNIGHAN PETER J. WEINBERGER AT& T Bell Laboratories Murray Hill, New Jersey A ADDISON-WESLEY•• PUBLISHING COMPANY Reading, Massachusetts • Menlo Park, California • New York Don Mills, Ontario • Wokingham, England • Amsterdam • Bonn Sydney • Singapore • Tokyo • Madrid • Bogota Santiago • San Juan This book is in the Addison-Wesley Series in Computer Science Michael A. Harrison Consulting Editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Aho, Alfred V. The AWK programming language. Includes index. I. AWK (Computer program language) I. Kernighan, Brian W. II. Weinberger, Peter J. III. Title. QA76.73.A95A35 1988 005.13'3 87-17566 ISBN 0-201-07981-X This book was typeset in Times Roman and Courier by the authors, using an Autologic APS-5 phototypesetter and a DEC VAX 8550 running the 9th Edition of the UNIX~ operating system. -~- ATs.T Copyright c 1988 by Bell Telephone Laboratories, Incorporated. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy ing, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Published simultaneously in Canada. UNIX is a registered trademark of AT&T. DEFGHIJ-AL-898 PREFACE Computer users spend a lot of time doing simple, mechanical data manipula tion - changing the format of data, checking its validity, finding items with some property, adding up numbers, printing reports, and the like. -

Linux Shell Script to Find Kernel Version from Multiple Servers Linux Shell Script That Will Login to Server Via Ssh and Get Kernel Version Via Uname -R Command

Linux Shell Script To Find Kernel Version From Multiple Servers Linux shell script that will login to server via ssh and get kernel version via uname -r command. List of all the servers are in server_list.txt file, script will take name by name and try to ssh with the root user and run uname -r command. Output will be written to variable and after into file with servername. This script helps system administrator who manage large linux servers , to take reports of what linux versions running. Here I have used uname -r but you can edit and use your own command as per your requirements. Source : http://linoxide.com/linux-shell-script/kernel-version-multiple/ Linux Shell Script #!/bin/bash #we user variable serverlist to keep there path to file with server names serverlist=’server_list.txt’ #we write in variable all server list servers=`cat $serverlist` #we use variable result to keep there path to file with result result=’result.txt’ #this print header to file with resilt using \t\t to add 2 tab symbols echo -e “Servername \t\t kernel version”> $result #this get each line of serverlist one by one and write to server variable for server in $servers do #this login to server by ssh and get uname -r kernel=`ssh root@${server} “uname -r”` #this write server name and kernel version separated by 2 tab to result file echo -e “$server \t\t $kernel” >> $result #end of for loop. done server_list.txt file # cat server_list.txt dev Linux Shell Script To Find Kernel Version From Multiple Servers 1 www.linoxide.com web1 svn Shell Script Output ./kernel_version.sh centos_node1@bobbin:~/Documents/Work/Bobbin$ cat result.txt Servername kernel version dev 3.3.8-gentoo web1 3.2.12-gentoo svn 3.2.12-gentoo Linux Shell Script To Find Kernel Version From Multiple Servers 2 www.linoxide.com. -

Compiling a Language

Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais – Department of Computer Science – Programming Languages Laboratory COMPILING A LANGUAGE DCC 888 Dealing with Programming Languages • LLVM gives developers many tools to interpret or compile a language: – The intermediate representaon – Lots of analyses and opDmiEaons Fhen is it worth designing a new • Fe can work on a language that already languageM exists, e.g., C, CKKI Lava, etc • Fe can design our own language. We need a front Machine independent Machine dependent end to convert optimizations, such as optimizations, such programs in the constant propagation as register allocation source language 2344555 to LLVM IR *+,-), 1#% ((0 !"#$%&'() '()./0 '()./0 '().- The Simple Calculator • To illustrate this capacity of LLAM, le2Ns design a very simple programming language: – A program is a funcDon applicaon – A funcDon contains only one argument x – Only the integer type exists – The funcDon body contains only addiDons, mulDplicaons, references to x, and integer constants in polish notaon: 1) Can you understand why we got each of these valuesM SR How is the grammar of our languageM The Architecture of Our Compiler !"#"$ %&$'"$ 2$34"$ (#)$ !!*05136' 1) Can you guess the meaning of the *&$(#)$ 0,1(#)$ diUerent arrowsM SR Can you guess the +,-(#)$ .//(#)$ role of each classM 3) Fhat would be a good execuDon mode for our systemM The Execuon Engine Our execuDon engine parses the expression, $> ./driver 4! converts it to a funcDon wriSen in LLAM IR, LIT * x x! Result: 16! compiles this funcDon, and runs it with the argument passed to the program in command $> ./driver 4! line. + x * x 2! Result: 12! Le2Ns start with our lexer.