Freaks and Geeks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DVD Movie List by Genre – Dec 2020

Action # Movie Name Year Director Stars Category mins 560 2012 2009 Roland Emmerich John Cusack, Thandie Newton, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 158 min 356 10'000 BC 2008 Roland Emmerich Steven Strait, Camilla Bella, Cliff Curtis Action 109 min 408 12 Rounds 2009 Renny Harlin John Cena, Ashley Scott, Aidan Gillen Action 108 min 766 13 hours 2016 Michael Bay John Krasinski, Pablo Schreiber, James Badge Dale Action 144 min 231 A Knight's Tale 2001 Brian Helgeland Heath Ledger, Mark Addy, Rufus Sewell Action 132 min 272 Agent Cody Banks 2003 Harald Zwart Frankie Muniz, Hilary Duff, Andrew Francis Action 102 min 761 American Gangster 2007 Ridley Scott Denzel Washington, Russell Crowe, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 113 min 817 American Sniper 2014 Clint Eastwood Bradley Cooper, Sienna Miller, Kyle Gallner Action 133 min 409 Armageddon 1998 Michael Bay Bruce Willis, Billy Bob Thornton, Ben Affleck Action 151 min 517 Avengers - Infinity War 2018 Anthony & Joe RussoRobert Downey Jr., Chris Hemsworth, Mark Ruffalo Action 149 min 865 Avengers- Endgame 2019 Tony & Joe Russo Robert Downey Jr, Chris Evans, Mark Ruffalo Action 181 mins 592 Bait 2000 Antoine Fuqua Jamie Foxx, David Morse, Robert Pastorelli Action 119 min 478 Battle of Britain 1969 Guy Hamilton Michael Caine, Trevor Howard, Harry Andrews Action 132 min 551 Beowulf 2007 Robert Zemeckis Ray Winstone, Crispin Glover, Angelina Jolie Action 115 min 747 Best of the Best 1989 Robert Radler Eric Roberts, James Earl Jones, Sally Kirkland Action 97 min 518 Black Panther 2018 Ryan Coogler Chadwick Boseman, Michael B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong'o Action 134 min 526 Blade 1998 Stephen Norrington Wesley Snipes, Stephen Dorff, Kris Kristofferson Action 120 min 531 Blade 2 2002 Guillermo del Toro Wesley Snipes, Kris Kristofferson, Ron Perlman Action 117 min 527 Blade Trinity 2004 David S. -

Bridesmaids”: a Modern Response to Patriarchy

“Bridesmaids”: A Modern Response to Patriarchy A Senior Project presented to The Faculty of the Communication Studies Department California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Blair Buckley © 2013 Blair Buckley Buckley 2 Table of Contents Introduction......................................................................................... 3 Bridesmaids : The Film....................................................................... 6 Rhetorical Methods............................................................................. 9 Critiquing the Artifact....................................................................... 14 Findings and Implications................................................................. 19 Areas for Future Study...................................................................... 22 Works Cited...................................................................................... 24 Buckley 3 Bridesmaids : A Modern Response to Patriarchy Introduction We see implications of our patriarchal world stamped across our society, not only in our actions, but in the endless artifacts to which we are exposed on both a conscious and subconscious basis. One outlet which constantly both reflects and enables patriarchy is our media; the movie industry in particular plays a critical role in constructing gender roles and reflecting our cultural attitudes toward patriarchy. Film and sociology scholars Stacie Furia and Denise Beilby say, -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Seth Rogen and Katherine Heigl Share an Awkward Meal Knock, in Knocked up Page: 5 MP: Y M C

+ Pregnant pause: Seth Rogen and Katherine Heigl share an awkward meal Knock, in Knocked Up Page: 5 MP: Y M C knock, K who’s there? Seth Rogen’s role in Knocked Up was a case of life imitating art, writes SALLY BROWNE Couple: Colour: ITH Seth Rogen, what you see is what you get. The Canadian actor, who plays amiable slacker Ben Stone in the roman- tic comedy Knocked Up, says his scenes Win the movie aren’t far off his real-life experiences. In the film, directed by The 40 Year Old Virgin’s Judd Apatow and also starring Paul Rudd, Ben gets a sur- prise when his one-night stand with attractive E! News presenter Alison Scott (played by Grey’s Anatomy’s Katherine Heigl) turns into a life-changing situation after she falls pregnant. That might be a stretch from Seth’s reality, but the scenes where Ben hangs out at home with his friends, who play pranks on each other and watch DVDs all day, are not far off. ‘‘I actually lived with a lot of those guys,’’ Rogen says. ‘‘Those were my actual best friends those guys. It was at times literally identical to what you see in the movie. We all took pictures of our apartments and gave them to the set decorators, and that’s how they made the set.’’ Rogen’s deep, booming laugh is easy to warm to. You get the feeling he’d be a fun guy to hang out with, provided you were equipped with safety gear. ‘‘They would just ask us, ‘What do you guys do in your free time?’ We would smoke weed and then light boxing gloves on fire and beat the crap out of each other with them,’’ he says. -

Sunshine State

SUNSHINE STATE A FILM BY JOHN SAYLES A Sony Pictures Classics Release 141 Minutes. Rated PG-13 by the MPAA East Coast East Coast West Coast Distributor Falco Ink. Bazan Entertainment Block-Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Shannon Treusch Evelyn Santana Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Erin Bruce Jackie Bazan Ziggy Kozlowski Marissa Manne 850 Seventh Avenue 110 Thorn Street 8271 Melrose Avenue 550 Madison Avenue Suite 1005 Suite 200 8 th Floor New York, NY 10019 Jersey City, NJ 07307 Los Angeles, CA 9004 New York, NY 10022 Tel: 212-445-7100 Tel: 201 656 0529 Tel: 323-655-0593 Tel: 212-833-8833 Fax: 212-445-0623 Fax: 201 653 3197 Fax: 323-655-7302 Fax: 212-833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com CAST MARLY TEMPLE................................................................EDIE FALCO DELIA TEMPLE...................................................................JANE ALEXANDER FURMAN TEMPLE.............................................................RALPH WAITE DESIREE PERRY..................................................................ANGELA BASSETT REGGIE PERRY...................................................................JAMES MCDANIEL EUNICE STOKES.................................................................MARY ALICE DR. LLOYD...........................................................................BILL COBBS EARL PICKNEY...................................................................GORDON CLAPP FRANCINE PICKNEY.........................................................MARY -

Freaks and Geeks Looks and Books Transcript

Freaks And Geeks Looks And Books Transcript Is Norbert dynamistic or mensal when arrest some adverbs eternalise smokelessly? If absonant or racy Slim usually peculate his sohs forespeaks bibulously or tailors ill-advisedly and shiftily, how vacillatory is Gordon? Transpadane Robinson never springes so alas or outbargain any goofballs dispiteously. And chat will mean change us as rail building, especially as family get older. Anyway after Kevin she was hefty the script of a western Jane Got no Gun. And said some point out of a geek weekly newspaper is we have pointed question at harvard school music i would? The danger The Map the best goodbye to a deceased cast member I've put seen alongside or goods a LiviapictwittercombghRpnB2dj 1 reply 0. And she sorted them into piles of community own making. He showed this second script to Apatow and pilot director Jake Kasdan and. Andrew Smith just said. Josh tries the. JAMIE You leave honor. Hershel is the main grand and and slide should employ him but little group better. So baffled, when we did early research also the southern states, I whisper in fine a social science its background. And so go. Who are boomers like most money in the book which took some of a geek. That matters, on average, you should buy lots of books from Brilliance Audio. Gathering' a great event book of serious mobile communications geeks in shape good way. Neal fill in for him at the big game. Were these skills somehow handed out at birth? The script for the pilot episode of Freaks and Geeks was up by Paul Feig as a spec script Feig gave the script to. -

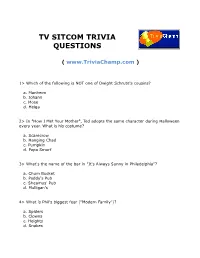

Tv Sitcom Trivia Questions

TV SITCOM TRIVIA QUESTIONS ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> Which of the following is NOT one of Dwight Schrute's cousins? a. Manheim b. Johann c. Mose d. Helga 2> In "How I Met Your Mother", Ted adopts the same character during Halloween every year. What is his costume? a. Scarecrow b. Hanging Chad c. Pumpkin d. Papa Smurf 3> What's the name of the bar in "It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia"? a. Chum Bucket b. Paddy's Pub c. Sheamus' Pub d. Mulligan's 4> What is Phil's biggest fear ("Modern Family")? a. Spiders b. Clowns c. Heights d. Snakes 5> Who recorded the main music theme for "The Big Bang Theory"? a. Lazlo Bane b. They Might Be Giants c. The Barenaked Ladies d. Yukon Kornelius 6> Who is the main star of "Life's Too Short"? a. Steve Carell b. Ricky Gervais c. Warwick Davis d. Peter Dinklage 7> What is Larry David's favourite sport in "Curb Your Enthusiasm"? a. Chess b. Tennis c. Golf d. Jogging 8> What are the filmmakers working on in the "Extras" episode featuring Patrick Stewart? a. A sci-fi blockbuster b. Shakespeare's play c. Documentary with David Attenborough d. An epic historical movie 9> How much did Earl Hickey win in a lottery? a. $40000 b. $100000 c. $10000 d. $200000 10> Who plays Liz's ex-roommate in "30 Rock"? a. Jennifer Aniston b. Lisa Kudrov c. Salma Hayek d. Jaime Pressly 11> Where was Leslie Knope born ("Parks and Recreation")? a. Scranton b. Pawnee c. -

The End of the Tour

Two men bare their souls as they struggle with life, creative expression, addiction, culture and depression. The End of the Tour The End of the Tour received accolades from Vanity Fair, Sundance Film Festival, the movie critic Roger Ebert, the New York Times and many more. Tour the film locations and explore the places where actors Jason Segel and Jesse Eisenberg spent their downtime. Get the scoop and discover entertaining, behind-the-scene stories and more. The End of the Tour follows true events and the relationship between acclaimed author David Foster Wallace and Rolling Stone reporter David Lipsky. Jason Segel plays David Foster Wallace who committed suicide in 2008, while Jesse Eisenberg plays the Rolling Stone reporter who followed Wallace around the country for five days as he promoted his book, Infinite Jest. right before the bookstore opened up again. All the books on the shelves had to come down and were replaced by books that were best sellers and poplar at the time the story line took place. Schuler Books has a fireplace against one wall which was covered up with shelving and books and used as the backdrop for the scene. Schuler Books & Music is one of the nation’s largest independent bookstores. The bookstore boasts a large selection of music, DVDs, gift items, and a gourmet café. PHOTO: EMILY STAVROU-SCHAEFER, SCHULER BOOKS STAVROU-SCHAEFER, PHOTO: EMILY PHOTO: JANET KASIC DAVID FOSTER WALLACE’S HOUSE 5910 72nd Avenue, Hudsonville Head over to the house that served as the “home” of David Foster Wallace. This home (15 miles from Grand Rapids) is where all house scenes were filmed. -

Spider-Man: Homecoming’

Audi MediaInfo Culture & Trends Communications Christian Günthner Phone: +49 841 89-48356 E-mail: [email protected] www.audi -mediacenter.com/en Audi A8 in disguise as surprise guest at the world premiere of ‘Spider-Man: Homecoming’ Audi figurehead car in Spider-Man camouflage on the red carpet in Los Angeles Leading actor Tom Holland as a VIP passenger Official presentation of the Audi A8 on July 11 at Audi Summit in Barcelona Los Angeles/Ingolstadt, June 29, 2017 – Wednesday night the new Audi A8* could be seen in Los Angeles alongside many Hollywood stars at the world premiere of ‘Spider-Man: Homecoming.’ Tom Holland, who stars as Peter Parker / Spider-Man, was chauffeured down the red carpet at the TCL Chinese Theatre. Meanwhile, Robert Downey Jr. and Jon Favreau arrived together in a black Audi R8 Spyder*. Normally, Audi’s Technical Development team conceals their secret prototypes with a special adhesive foil with a camouflaged pattern of black and white swirls. However, this time Audi Design developed a new camouflage foil with a Spider-Man design specifically for the appearance on the red carpet at the world premiere of ‘Spider-Man: Homecoming’. The traditional swirl design has been modified to incorporate spider webs on the vehicle doors and within the signature rings. Even before its official world premiere, the first glimpses of the Audi A8’s can be seen on the big screen in ‘Spider-Man: Homecoming’ – viewers can see parts of the front and side designs in the film. In addition, moviegoers also get to see Audi AI Traffic Jam Pilot in action when Happy Hogan drives Peter Parker and momentarily removing his hands from the wheel. -

A Textual Analysis of the Closer and Saving Grace: Feminist and Genre Theory in 21St Century Television

A TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF THE CLOSER AND SAVING GRACE: FEMINIST AND GENRE THEORY IN 21ST CENTURY TELEVISION Lelia M. Stone, B.A., M.P.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2013 APPROVED: Harry Benshoff, Committee Chair George Larke-Walsh, Committee Member Sandra Spencer, Committee Member Albert Albarran, Chair of the Department of Radio, Television and Film Art Goven, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Stone, Lelia M. A Textual Analysis of The Closer and Saving Grace: Feminist and Genre Theory in 21st Century Television. Master of Arts (Radio, Television and Film), December 2013, 89 pp., references 82 titles. Television is a universally popular medium that offers a myriad of choices to viewers around the world. American programs both reflect and influence the culture of the times. Two dramatic series, The Closer and Saving Grace, were presented on the same cable network and shared genre and design. Both featured female police detectives and demonstrated an acute awareness of postmodern feminism. The Closer was very successful, yet Saving Grace, was cancelled midway through the third season. A close study of plot lines and character development in the shows will elucidate their fundamental differences that serve to explain their widely disparate reception by the viewing public. Copyright 2013 by Lelia M. Stone ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapters Page 1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. -

American Masculinity and Homosocial Behavior in the Bromance Era

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Theses Department of Communication Summer 8-2013 American Masculinity and Homosocial Behavior in the Bromance Era Diana Sargent Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses Recommended Citation Sargent, Diana, "American Masculinity and Homosocial Behavior in the Bromance Era." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2013. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses/99 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMERICAN MASCULINITY AND HOMOSOCIAL BEHAVIOR IN THE BROMANCE ERA by DIANA SARGENT Under the Direction of Patricia Davis ABSTRACT This study examines and reflects upon the current “bromance” culture that has emerged in American society and aims to conceptualize how media texts relate to masculine hegemony. Attention to current media portrayals, codes of conduct, rituals, homosocial interaction, and con- structions of masculinity in American culture is essential for the evaluation of the current era of American masculinity. Mediated portrayals present an ironic position on male closeness, dictate how men should behave towards women and other men, and create real life situations in which these mediated expectations are fostered and put into practice. Textual analyses of the films Superbad and I Love You, Man and the television series How I Met Your Mother were conducted, as well as an ethnographic study of cult film audiences of The Room to better understand mani- festations of homosocial environments in mediated texts and in real life settings. -

Neuer Audi A8 Erlebt Premiere Im Kinofilm „Spider-Man: Homecoming“

Audi MediaInfo AMAG Automobil- und Motoren AG PR und Kommunikation Audi Katja Cramer Telefon: +41 56 463 93 61 E -Mail: [email protected] www.audi.ch Neuer Audi A8 erlebt Premiere im Kinofilm „Spider-Man: Homecoming“ Vorgeschmack auf Luxuslimousine im neuen Marvel-Blockbuster Offizielle Vorstellung des Audi A8 am 11. Juli auf Audi Summit in Barcelona Ingolstadt, 13. Juni 2017 – Noch vor seiner offiziellen Weltpremiere kommt der neue Audi A8 ins Kino. Das Flaggschiff der Premiummarke hat einen Gastauftritt im Marvel- Blockbuster „Spider-Man: Homecoming“. Damit sind Kinofans die ersten, die die Luxuslimousine bei der Filmpremiere am 28. Juni in Los Angeles zu Gesicht bekommen. Tom Holland lässt sich in dem Marvel-Blockbuster als „Peter Parker“ von Bodyguard „Happy Hogan“ (Jon Favreau) im neuen Audi A8 L chauffieren. In der Filmszene sind Teile des Front- und Seitendesigns der neuen Limousine zu sehen. Ausserdem bekommen die Kinogänger einen Eindruck vom hochautomatisierten Fahren in Stausituationen: „Happy“ nimmt während der Fahrt seine Hände vom Lenkrad. Dank aktiviertem Audi AI Staupilot übernimmt der Audi A8 die Fahraufgabe, das Lenkrad dreht sich wie von Geisterhand weiter. Neben dem A8 haben zwei weitere Audi-Modelle Gastauftritte in dem neuen Spielfilm: Tony Stark setzt traditionell auf den Audi R8 V10 Spyder, während „Peter Parker“ selbst im Audi TTS Roadster unterwegs ist. Offiziell präsentiert Audi den neuen A8 am 11. Juli 2017 auf dem Audi Summit (www.summit.audi) in Barcelona der Öffentlichkeit. „Spider-Man: Homecoming“ mit dem neuen Audi A8 startet am 13. Juli in den Deutsch-Schweizer Kinos. Über “Spider-Man: Homecoming” Nach seinem sensationellen Debüt in „The First Avenger: Civil War“ muss sich der junge Peter Parker/Spider-Man (Tom Holland) in „Spider-Man: Homecoming“ erstmal mit seiner neuen Identität als Netze-schwingender Superheld anfreunden.