Final Report 29 March 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May 2016 Suzanne Burgess

May 2016 Suzanne Burgess Saving the small things that run the planet Summary The John Muir Way, opened in 2014, stretches 134 miles through nine local authority areas including West Lothian. This B-lines project, the first in Scotland, has identified new opportunities for grassland habitat creation, enhancement and management along the route of the John Muir Way as it passes through the north of West Lothian as well as 1.86 miles either side of this. Through this mapping exercise a number of sites have been identified including 7 schools and nurseries; 3 care homes; 8 places of worship and cemeteries; 2 historic landmarks and buildings; and 1 train station. Additionally, 3 golf courses (73.8 ha), 9 public parks and play spaces (267.81 ha) and 1 country park (369 ha) were identified. There are a number of sites within this project that have nature conservation designations, including 23 Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (496.37 ha) and 5 Sites of Special Scientific Interest (84.13 ha). A further 2 sites have previously been identified as having an Open Mosaic of Habitat on Previously Developed Land with a total of 34.7 ha. By mapping new opportunities this will aid in the future development of projects that will provide real benefits to our declining populations of pollinating insects of bees, wasps, hoverflies and butterflies as well as other wildlife that these habitats support. 1 Contents Page Page Number 1. Introduction 3 1.1 B-lines 3 2. Method 4 3. Results 4 4. Discussion 8 4.1 Schools 8 4.2 Care Homes 9 4.3 Places of Worship and Cemeteries 9 4.4 Historic Landmarks and Buildings 10 4.5 Train Stations 10 4.6 Golf Courses 10 4.7 Public Parks and Play Spaces 11 4.8 Country Parks 12 4.9 Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation 12 4.10 Sites of Special Scientific Interest 12 4.11 Open Mosaic Habitat on Previously Developed Land 13 4.12 Other Opportunities 13 5. -

Dear Fiona I Am Writing to Object to the Proposed Use of the Vacant Land

From: XXXXXXXX Sent: 07 June 2011 01:33 To: McBrierty, Fiona Subject: Planning Brief Consultation Dear Fiona I am writing to object to the proposed use of the vacant land next to the Almondvale Roundabout (Junction with Alderstone Road and Charlesfield Road). At present this piece of land is a green area full of wildlife. • We need to preserve these conservation greenbelt linking areas within the town boundary. • The amenity of an open environment gives added value to the community and a sense of wellbeing. • The wooded areas are full of wild life mainly because they are undisturbed. This will not be the case if more housing is added. • The cemetery in Adambrae is quiet and serene. I am sure the residents of the town, and of the surrounding area, would like it to remain so. The site area of the cemetery will grow over the years to come and it would seem sensible if ground was available for that purpose. • 1 in 5 houses in Ireland are lying vacant due to the economic downturn caused by overproduction of housing. We do not want that to be the case here. There are plans for a considerable number of additional housing developments throughout West Lothian and this small area should be excluded. • The wildlife corridor must be preserved and should not be concreted over, when there are many other, non-wildlife sites, available. • The traffic is bad enough at the Almondvale roundabout without the addition of another arm. • Adambrae and Livingston village communities are quite respected small communities and the addition of extra housing could reduce their value. -

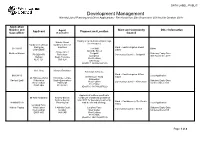

Development Management List of Delegated Decisions - 30Th November 2018

DATA LABEL: OFFICIAL Development Management List of Delegated Decisions - 30th November 2018 The following decisions will be issued under delegated powers unless any Member requests that an application is reported to the Development Management Committee for determination. Such requests must be made on the attached form, which should be completed and sent for the attention of the Development Management Manager to [email protected] no later than 12 Noon, 7 days from the date of this list. Ref. No.: 0996/H/18 Recommendation: Refuse Permission Proposal: Extension to house Address: 49 Maukeshill Court,Livingston Village, Livingston, West Lothian, EH54 7AX (Grid Ref: 303994,666937) Applicant: Mr S Morrison Type: Local Application Ward: Livingston North Case Officer: Thomas Cochrane Summary of Representations None Officers report The dwelling is located at the entrance of a housing estate which were built as bungalows. It is one of a row of four properties, three of which are still single storey; the application property had its roof raised in 1987, without planning permission, and consequently is a two storey house, with the appearance of a chalet villa, with two upstairs bedrooms contained within the roof. The property is finished in white render and retains its original front elevation of two windows and an entrance door; there is an additional upstairs window to the front and back which was added when the roof was raised. The properties in Maukeshill Court are visually similar, and all have a small single detached garage to the west, enhancing the visual continuity of the streetscene. It is proposed to extend the property by integrating the garage and adding further accommodation to the upper floor. -

The Mineral Resources of the Lothians

The mineral resources of the Lothians Information Services Internal Report IR/04/017 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY INTERNAL REPORT IR/04/017 The mineral resources of the Lothians by A.G. MacGregor Selected documents from the BGS Archives No. 11. Formerly issued as Wartime pamphlet No. 45 in 1945. The original typescript was keyed by Jan Fraser, selected, edited and produced by R.P. McIntosh. The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Ordnance Survey licence number GD 272191/1999 Key words Scotland Mineral Resources Lothians . Bibliographical reference MacGregor, A.G. The mineral resources of the Lothians BGS INTERNAL REPORT IR/04/017 . © NERC 2004 Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2004 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available from the BGS Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG Sales Desks at Nottingham and Edinburgh; see contact details 0115-936 3241 Fax 0115-936 3488 below or shop online at www.thebgs.co.uk e-mail: [email protected] The London Information Office maintains a reference collection www.bgs.ac.uk of BGS publications including maps for consultation. Shop online at: www.thebgs.co.uk The Survey publishes an annual catalogue of its maps and other publications; this catalogue is available from any of the BGS Sales Murchison House, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA Desks. 0131-667 1000 Fax 0131-668 2683 The British Geological Survey carries out the geological survey of e-mail: [email protected] Great Britain and Northern Ireland (the latter as an agency service for the government of Northern Ireland), and of the London Information Office at the Natural History Museum surrounding continental shelf, as well as its basic research (Earth Galleries), Exhibition Road, South Kensington, London projects. -

DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE Report by Head Of

DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE Report by Head of Planning, Economic Development and Regeneration 1 DESCRIPTION Planning permission in principle for the erection of a house at 5 Pardovan Holding, Philpstoun 2 DETAILS Reference no. 0592/P/17 Owner of site Oakwell Nursery Applicant Oakwell Nursery Ward & local Linlithgow members Councillor Tom Kerr Councillor Tom Conn Councillor David Tait Case officer Matthew Watson Contact details 01506 283536 [email protected]. uk Reason for referral to Development Management Committee: Referred by the Development Management Manager 3 RECOMMENDATION Refuse planning permission in principle. 4. DETAILS OF THE PROPOSAL AND BACKGROUND 4.1 Planning permission in principle is sought for erection of a house between the main nursery building at Oakwell Nursery and the nursery building at the west of the site. 4.2 The application is linked to applications 0536/FUL/17 and 0593/P/17 at the same site. 4.5 Committee previously considered and refused an application for five houses on this site at the June 14th Development Management Committee. The refusal of that application has been appealed to Scottish Ministers. History 4.6 0260/FUL/17: Erection of five dwellinghouses, Refused, 23/06/2017 (Appeal submitted to the DPEA) 4.7 0725/FUL/13: Erection of a 39 sqm extension to nursery, Granted, 19/12/2013 4.8 0452/FUL/09: Conversion of dog kennels to form extension to existing childrens nursery and formation of car park, Granted, 11/09/2009 4.9 1065/FUL/08: Continued siting of portacabin and siting of new -

Development Management Weekly List of Planning and Other Applications - Received from 30Th September 2019 to 6Th October 2019

DATA LABEL: PUBLIC Development Management Weekly List of Planning and Other Applications - Received from 30th September 2019 to 6th October 2019 Application Number and Ward and Community Other Information Applicant Agent Proposal and Location Case officer (if applicable) Council Display of an illuminated fascia sign Natalie Gaunt (in retrospect). Cardtronics UK Ltd, Cardtronic Service trading as Solutions Ward :- East Livingston & East 0877/A/19 The Mall Other CASHZONE Calder Adelaide Street 0 Hope Street Matthew Watson Craigshill Statutory Expiry Date: PO BOX 476 Rotherham Community Council :- Craigshill Livingston 30th November 2019 Hatfield South Yorkshire West Lothian AL10 1DT S60 1LH EH54 5DZ (Grid Ref: 306586,668165) Ms L Gray Maxwell Davidson Extenison to house. Ward :- East Livingston & East 0880/H/19 Local Application 20 Hillhouse Wynd Calder 20 Hillhouse Wynd 19 Echline Terrace Kirknewton Rachael Lyall Kirknewton South Queensferry Statutory Expiry Date: West Lothian Community Council :- Kirknewton West Lothian Edinburgh 1st December 2019 EH27 8BU EH27 8BU EH30 9XH (Grid Ref: 311789,667322) Approval of matters specified in Mr Allan Middleton Andrew Bennie conditions of planning permission Andrew Bennie 0462/P/17 for boundary treatments, Ward :- Fauldhouse & The Breich 0899/MSC/19 Planning Ltd road details and drainage. Local Application Valley Longford Farm Mahlon Fautua West Calder 3 Abbotts Court Longford Farm Statutory Expiry Date: Community Council :- Breich West Lothian Dullatur West Calder 1st December 2019 EH55 8NS G68 0AP West Lothian EH55 8NS (Grid Ref: 298174,660738) Page 1 of 8 Approval of matters specified in conditions of planning permission G and L Alastair Nicol 0843/P/18 for the erection of 6 Investments EKJN Architects glamping pods, decking/walkway 0909/MSC/19 waste water tank, landscaping and Ward :- Linlithgow Local Application Duntarvie Castle Bryerton House associated works. -

6 the Avenue Philpstoun, Scotland Offers Over £273,000 Hallidayproperty.Co.Uk

Bedrooms: 3 Bathrooms: 2 Receptions: 3 6 The Avenue Philpstoun, Scotland Offers Over £273,000 hallidayproperty.co.uk Description Offering a rare opportunity to purchase this Edwardian, professionally Dining Room (4.40m x 4.60m) extended, terraced home situated in a quiet cul-de-sac in the village of The very spacious dining room has a front facing window. Original Philipstoun, close to Linlithgow. The property offers all the benefits of wooden doors, shelved cupboard, fire surround, picture rail, cornicing, modern living whilst retaining many of its charming period features. access to inner hall and French doors into lounge. The accommodation comprises on the ground floor; Lounge, kitchen, dining room, family room, hall, bathroom and a double bedroom. The Hall upper floor benefits from two good sized bedrooms and a further Access into the bedroom, bathroom and walk in cupboard. bathroom. Warmth is provided by gas central heating and double glazing. Externally, there is parking to the front of the property with a Bedroom 1 (4.85m x 2.87m) lovely, landscaped garden to the rear. Neutrally decorated with carpet flooring, front facing window, built in wardrobes and radiator. Location Bathroom (1.94m x 1.87m) Philipstoun is a small village in West Lothian which originated in the oil A fully tiled bathroom with white W.C. washbasin and P-shaped bath shale mining boom of the 19th century. Surrounded by rich arable with overhead Mira shower. Glass screen, mirrored cabinet, heated farm land, the village has a Community Education Centre, bowling towel rail and opaque window. green and a Category B listed church and is situated close to the historic county town of Linlithgow. -

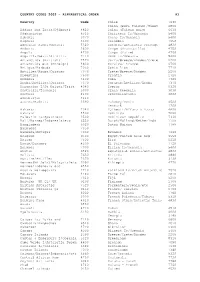

Country Codes 2002 – Alphabetical Order A1

COUNTRY CODES 2002 – ALPHABETICAL ORDER A1 Country Code Chile 7640 China (excl Taiwan)/Tibet 6800 Affars and Issas/Djibouti 4820 China (Taiwan only) 6630 Afghanistan 6510 Christmas Is/Oceania 5400 Albania 3070 Cocos Is/Oceania 5400 Algeria 3500 Colombia 7650 American Samoa/Oceania 5320 Comoros/Antarctic Foreign 4830 Andorra 2800 Congo (Brazzaville) 4750 Angola 4700 Congo (Zaire) 4760 Anguilla/Nevis/St Kitts 7110 Cook Is/Oceania 5400 Antarctica (British) 7520 Corfu/Greece/Rhodes/Crete 2200 Antarctica etc (Foreign) 4830 Corsica/ France 0700 Antigua/Barbuda 7030 Costa Rica 7710 Antilles/Aruba/Curacao 7370 Crete/Greece/Rhodes 2200 Argentina 7600 Croatia 2720 Armenia 3100 Cuba 7320 Aruba/Antilles/Curacao 7370 Curacao/Antilles/Aruba 7370 Ascension I/St Helena/Trist 4040 Cyprus 0320 Australia/Tasmania 5000 Czech Republic 3030 Austria 2100 Czechoslovakia 3020 Azerbaijan 3110 Azores/Madeira 2390 Dahomey/Benin 4500 Denmark 1200 Bahamas 7040 Djibouti/Affars & Issas 4820 Bahrain 5500 Dominica 7080 Balearic Is/Spain/etc 2500 Dominican Republic 7330 Bali/Borneo/Indonesia/etc 6550 Dutch/Holland/Netherlnds 1100 Bangladesh 6020 Dutch Guiana 7780 Barbados 7050 Barbuda/Antigua 7030 Ecuador 7660 Belgium 0500 Egypt/United Arab Rep 3550 Belize 7500 Eire 0210 Benin/Dahomey 4500 El Salvador 7720 Bermuda 7000 Ellice Is/Oceania 5400 Bhutan 6520 Equatorial Guinea/Antarctic 4830 Bolivia 7630 Eritrea 4840 Bonaire/Antilles 7370 Estonia 3130 Borneo(NE Soln)/Malaysia/etc 6050 Ethiopia 4770 Borneo/Indonesia etc 6550 Bosnia Herzegovina 2710 Falkland Is/Brtsh Antarctic -

WARD PROFILE 1 : Linlithgow

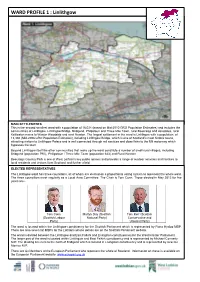

WARD PROFILE 1 : Linlithgow MAIN SETTLEMENTS This is the second smallest ward with a population of 16,034 (based on Mid-2010 GRO Population Estimates) and includes the communities of Linlithgow, Linlithgow Bridge, Bridgend, Philpstoun and Three Mile Town, rural Beecraigs and Acredales, rural Kettleston mains to Wester Woodside and rural Newton. The largest settlement in the ward is Linlithgow with a population: of 13,360 (Mid-2008 GRO Population Estimates), including Linlithgow Bridge, which is one of Scotland’s most historic towns, attracting visitors to Linlithgow Palace and is well connected through rail services and close links to the M9 motorway which bypasses the town. Beyond Linlithgow itself the other communities that make up the ward constitute a number of small rural villages, including Bridgend (population 790), Philipstoun / Three Mile Town (population 643) and Rural Newton. Beecraigs Country Park is one of West Lothian’s key public spaces and provides a range of outdoor activities and facilities to local residents and visitors form Scotland and further afield. ELECTED REPRESENTATIVES The Linlithgow ward has three councillors, all of whom are elected on a proportional voting system to represent the whole ward. The three councillors meet regularly as a Local Area Committee. The Chair is Tom Conn. Those elected in May 2012 for five years are:- Tom Conn Martyn Day (Scottish Tom Kerr (Scottish (Scottish Labour National Party) Conservative and Party) Unionist Party) The ward is located within the Linlithgow constituency for the Scottish Parliament which is represented by Fiona Hyslop MSP. There are also seven list MSPs for the Lothians whose details are on the Scottish Parliament website. -

MURIESTON COMMUNITY COUNCIL MINUTES of MEETING on 13 SEPTEMBER 2018 Held at Williamston Primary School at 7 Pm Web

MURIESTON COMMUNITY COUNCIL MINUTES OF MEETING ON 13 SEPTEMBER 2018 held at Williamston Primary School at 7 pm web: http://murieston.communitycouncil.org.uk 1. Present: Chris Dryden, Carol Hallesy, Arthur Marris, Ian Brown, Davidson McQuarrie, David Cooper, Lorna Cooper, Frank Mustard, Ron Skirving; Councillor Lawrence Fitzpatrick Apologies: Tania Armstrong, Kevin Kerr, Nick Lansdell; Councillor Moira Shemilt Other attendees: Ken Kirk; Brian Johnstone and Dean Swift from Livingston Village Committee Council; Christine Hay, Frances and Peter Jeppesen from Bellsquarry & Adambrae Community Council; Jane Beggie, Tree & Woodland Officer, West Lothian Council; Jean Frame, site manager and Nick Porter, assistant site manager with Woodland Trust 2. Minutes of the Meeting on 14 June 2018: Acceptance of the minutes of the regular meeting on 14 June was proposed by Frank Mustard and seconded by Arthur Marris, subject to minor changes. Carried. 3. Matters Arising: As the developers of the housing development at Wellhead Farm are financing the new footway at Murieston Road, Council funding for this work has been re-allocated for an upgrade of the path at Newpark Road. 4. Presentation by Woodland Trust re. TPO Planning Application (Ref. 0575/TPO/18): Jane Beggie from West Lothian Council, and Jean Frame and Nick Porter from Woodland Trust attended the meeting to provide information on the recent planning application to remove 18 trees in Williamston Wood beside Williamston School which is covered by a TPO order. Jean Frame from Woodland Trust outlined the background to the planning application. There are 13 community woodlands in Livingston which are managed by the Woodland Trust. High risk zones, which are so designated being beside schools and paths etc., are surveyed every 1 to 2 years, and, as a result of an inspection, trees suspected of disease have been identified at Williamston Wood. -

Linlithgow Ward Plan

MULTI-MEMBER WARD OPERATIONAL PLAN FOR LINLITHGOW 2014-2017 Working together for a safer Scotland Contents Foreword 1 Introduction 2 Linlithgow Ward Profile 3 Local Operational Assessment 6 Achieving Local Outcomes 7 Priority Setting 8 SFRS Resources in West Lothian 9 Priorities, Actions and Outcomes 11 1. Local Risk Management and Preparedness 11 2. Reduction of Accidental Dwelling Fires 13 3. Reduction in Fire Casualties and Fatalities 15 4. Reduction of Deliberate Fire Setting 17 5. Reduction of Fires in Non-Domestic Properties 19 6. Reduction in Casualties from Non-Fire Emergencies 21 7. Reduction of Unwanted Fire Alarm Signals 23 Review 25 Feedback 25 Glossary of Terms 26 LINLITHGOW Multi Member Ward Operational Plan 2014-17 FOREWORD Welcome to the Scottish Fire & Rescue Services (SFRS) Operational Plan for the Local Authority Multi Member Ward Area of Linlithgow. This plan is the mechanism through which the aims of the SFRS’s Strategic Plan 2013 – 2016 and the Local Fire and Rescue Plan for West Lothian 2014-2017 are delivered to meet the agreed needs of the communities within the Linlithgow ward area. This plan sets out the priorities and objectives for the SFRS within the Linlithgow ward area for 2014 – 2017. The SFRS will continue to work closely with our partners in the Linlithgow ward area to ensure we are all “Working Together for a safer Scotland” through targeting risks to our communities at a local level. This plan is aligned to the Community Planning Partnership structures within West Lothian. Through partnership working, we aim to deliver continuous improvement in our performance and effective service delivery in our area of operations. -

Community Council Office Bearers – Revised May 2017

COMMUNITY COUNCIL OFFICE BEARERS – REVISED MAY 2017 For further information about Community Councils in West Lothian please visit www.westlothian.gov.uk/communitycouncils ADDIEWELL & LOGANLEA COMMUNITY COUNCIL FAULDHOUSE & THE BREICH VALLEY WARD Chair Vice Chair Treasurer Secretary Fiona Duncan David Fitzcharles Lesley Martin Anne Walsh 14 Ross Court Hawthorn Cottage Elm Cottage, Muirhall 8 Faraday Place Addiewell Muirhall Addiewell Addiewell West Lothian Addiewell West Lothian West Lothian EH55 8HE EH55 8NL EH55 8NL EH55 8NG 01501 763839 [email protected] ARMADALE COMMUNITY COUNCIL ARMADALE & BLACKRDIGE WARD Chair Vice Chair Treasurer Secretary John McKee John Watson Alison Muir Hugh Cockburn 28 Glenside Gardens 16 Millburn Crescent 2 Baird Road c/o 28 Glenside Gardens Armadale Armadale Armadale Armadale West Lothian West Lothian West Lothian West Lothian EH48 3RA EH48 3RB EH48 3 EH48 3RE 07743 672 092 07801 792 917 [email protected] [email protected] 15/5/2017 BATHGATE COMMUNITY COUNCIL BATHGATE WARD Chair Vice Chair Treasurer Secretary Ronald MacLeod Billy Johnston Donald Stavert Debbie Halloran 11 Inch Crescent 3 Avon Road 43 Bruce Street 71 Cardross Avenue Bathgate Bathgate Bathgate Broxburn West Lothian West Lothian West Lothian West Lothian EH48 1EU EH48 4HP EH48 2TJ EH52 6HD 01506 630914 07841 700 074 [email protected] [email protected] BELLSQUARRY & ADAMBRAE COMMUNITY COUNCIL LIVINGSTON SOUTH WARD Chair Vice Chair Treasurer Secretary Kenneth Logan Jill Wilkie James Wilkie Christine