TULLY, KIVAS, Architect, Civil Engineer, and Civil Servant; B. 1820

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making Land on the Toronto Waterfront in the 1850S Thomas Mcilwraith

Document generated on 09/24/2021 10:01 p.m. Urban History Review Revue d'histoire urbaine Digging Out and Filling In Making Land on the Toronto Waterfront in the 1850s Thomas McIlwraith Volume 20, Number 1, June 1991 Article abstract A half-million square metres (50 hectares) was brought in to railroad and URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1017560ar commercial use at wharfage-level along the Toronto lakefront during the DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1017560ar 1850s. This major engineering project involved cutting down the terrace south of Front Street, and this was the source of most of the fill dumped into the Bay. See table of contents Neither railroad cars nor harbour dredges were capable of delivering the additional material necessary for building anticipated port lands, and many parts of the waterfront remained improperly filled for decades. The land-area Publisher(s) that was created should be regarded as a byproduct of short-run, selfish commercial interests, abetted by a City Council that gave only lip-service to the Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine concept of a parklike lakefront. ISSN 0703-0428 (print) 1918-5138 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article McIlwraith, T. (1991). Digging Out and Filling In: Making Land on the Toronto Waterfront in the 1850s. Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine, 20(1), 15–33. https://doi.org/10.7202/1017560ar All Rights Reserved © Urban History Review / Revue d'histoire urbaine, 1991 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. -

NIAGARA ROCKS, BUILDING STONE, HISTORY and WINE

NIAGARA ROCKS, BUILDING STONE, HISTORY and WINE Gerard V. Middleton, Nick Eyles, Nina Chapple, and Robert Watson American Geophysical Union and Geological Association of Canada Field Trip A3: Guidebook May 23, 2009 Cover: The Battle of Queenston Heights, 13 October, 1812 (Library and Archives Canada, C-000276). The cover engraving made in 1836, is based on a sketch by James Dennis (1796-1855) who was the senior British officer of the small force at Queenston when the Americans first landed. The war of 1812 between Great Britain and the United States offers several examples of the effects of geology and landscape on military strategy in Southern Ontario. In short, Canada’s survival hinged on keeping high ground in the face of invading American forces. The mouth of the Niagara Gorge was of strategic value during the war to both the British and Americans as it was the start of overland portages from the Niagara River southwards around Niagara Falls to Lake Erie. Whoever controlled this part of the Niagara River could dictate events along the entire Niagara Peninsula. With Britain distracted by the war against Napoleon in Europe, the Americans thought they could take Canada by a series of cross-border strikes aimed at Montreal, Kingston and the Niagara River. At Queenston Heights, the Niagara Escarpment is about 100 m high and looks north over the flat floor of glacial Lake Iroquois. To the east it commands a fine view over the Niagara Gorge and river. Queenston is a small community perched just below the crest of the escarpment on a small bench created by the outcrop of the Whirlpool Sandstone. -

City of St. Catharines Designation of Rodman Hall Under Part IV

Corporate Report Report from Planning and Building Services, Planning Services Date of Report: April 19, 2018 Date of Meeting: May 23, 2018 Report Number: PBS-111-2018 File: 10.64.187 Subject: Designation of 109 St. Paul Crescent (Rodman Hall) under Part IV of Ontario Heritage Act Recommendation That Council designate the interior and exterior of the building located at 109 St. Paul Crescent (Rodman Hall) and grounds to be of cultural heritage value or interest pursuant to Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act, for reasons (see Appendix 7) set forth in the report from Planning and Building Services, dated April 19, 2018; and That the City Clerk be directed to give notice of Council’s intent pursuant to the Ontario Heritage Act; and That the City Solicitor be directed to prepare the necessary by-laws to give effect to Council’s decision if no appeals are submitted; and That upon expiration of the appeal period, the Clerk be directed to forward any appeals to the Conservation Review Board; and Further, that the Clerk be directed to make the necessary notifications. FORTHWITH Summary The St. Catharines Heritage Advisory Committee (SCHAC) is recommending that the building (interior and exterior) and grounds at 109 St. Paul Crescent, be designated under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act. Staff concur with its recommendation under the Ontario Heritage Act. This report summarizes the background, conclusions of the heritage research, consultation, and Provincial and Official Plan policies that support heritage conservation in St. Catharines. The Ontario Heritage Act enables the council of a municipality to designate a property within the municipality to be of cultural heritage or value or interest if the property meets prescribed criteria. -

Heritage Churches in the Niagara Region: an Essay on the Interpretation of Style Malcolm Thurlby

Document generated on 09/28/2021 7:11 a.m. Journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada Le Journal de la Société pour l'étude de l'architecture au Canada Heritage Churches in the Niagara Region: An Essay on the Interpretation of Style Malcolm Thurlby Volume 43, Number 2, 2018 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1058039ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1058039ar See table of contents Publisher(s) SSAC-SEAC ISSN 2563-8696 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Thurlby, M. (2018). Heritage Churches in the Niagara Region: An Essay on the Interpretation of Style. Journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada / Le Journal de la Société pour l'étude de l'architecture au Canada, 43(2), 67–95. https://doi.org/10.7202/1058039ar Copyright © SSAC-SEAC, 2019 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ ANALYSIS | ANALYSE HERITAGE CHURCHES IN THE NIAGARA REGION: AN ESSAY ON THE INTERPRETATION OF STYLE1 MALCOLM THURLBY, PH.D., F.S.A., teaches MALCOLM THURLBY art and architectural history at York University, Toronto. His research concentrates on Romanesque and Gothic architecture and sculpture from the eleventh to the thirteenth century, and nineteenth-century Canadian his paper is an expanded ver- architecture. -

Architectural Records Collection

Description and Finding Aid ARCHITECTURAL RECORDS COLLECTION Including records from: acc. 1986-0098 acc. 1988-0059 acc. 2005-0032 Prepared by James Roussain, 2011-2012 Architectural Records Collection page 2 of 307 Introduction The construction history of the University of Trinity College as seen through its collection of architectural drawings, spans two centuries of different styles and contents, from the hand-painted watercolour drawings done on heavy paper of William Hay 1857 to the machine-generated drawings of more recent years. Among the plans listed in this finding aid are those related both directly to the physical plant of Trinity College, and those related indirectly by reason of their associational history including St. Hilda's College, the Gerald Larkin Academic Building, George Ignatieff Theatre, Munk Centre and other records as listed; all records and materials are listed chronologically within their organization series. Requests for information from researchers which previously went unanswered for lack of access to architectural plans can now be responded to with greater alacrity and with more attention given to identification by means of detailed descriptions. As several incomplete efforts have been made to comprehensively organize these materials, several accession numbers have come to be associated with these records. Where possible, all numbers associated with a record have been included in their description. Records are listed as follows: Records from the Offices of the Bursar and Building Manager, University of Trinity College, 988 0059/ A1857-1858 (01) 01 …where 988-0059 is the accession number, / A1857-1858 is the series number as defined by the record's date of creation or use, (01) is the section number, and 01 being the item's position within the section. -

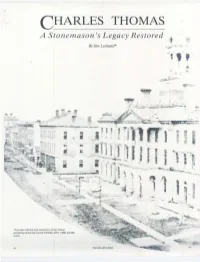

CHARLES THOMAS a Stonemason's Legacy Restored

CHARLES THOMAS A Stonemason's Legacy Restored . ~ 'Reprinted with the kind permission of the Ontario Genealogical Society journal Families (28:2, 1989) and the author. What is a genealogist to do when he/she reads statements in popular and respected . publications crediting another person with an achievement that we know proudly belongs to a relative? What if such statements are often written as absolute fact, yet are contradictory to our own family history? What if every time one picks up a book or reads a magazine article about the subject in question, that glaring "mistake" is found? One might try to ignore the inaccuracies. But most family historians would do as much as possible to correct them. I was caught in just such a problem in the spring and summer of 1986. In my case the inaccuracy was a fully understandable case of mistaken identity. But because it appeared in print again and again, I grew increasingly frustrated. I decided to try to set the record straight. -•~, Victoria Hall, Cobourg, Ontario, circa 1860. This may well be the earliest photograph of Victoria Hall. The three-storey building to the extreme left is the Bank of Montreal, designed by J.H. Spring Ie. Directly behind Victoria Hall is the Market Building, apparently designed by IVvas Tully and constructed as part of the town hall project. (Art Gallery of Northumberland, NEC) thas alwaysbeen the contention in our family that my maternal too, was born in Wales. The story goes on to say that after the work on Igreat-great-great uncle, a Welsh stonemason and master Victoria Hall was completed, Charles Thomas left Cobourg and, some builder named Charles Thomas Thomas (1820-1867), executed the time later, was killed on a bridge building project in the United States. -

Ce Document Est Tiré Du Registre Aux Fins De La Loi Sur Le Patrimoine De L

This document was retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act Register, which is accessible through the website of the Ontario Heritage Trust at www.heritagetrust.on.ca. Ce document est tiré du registre aux fins de la Loi sur le patrimoine de l’Ontario, accessible à partir du site Web de la Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien sur www.heritagetrust.on.ca. 0r\T,til0 litRiTtCI TRTST i:ii I i :iij Town of Whitby -?FtP*{.{r* Office of the Town Clerk 575 Rossland Road East, Whitby, ON L1N 2M8 www.whitbv.ca April 30, 2015 Sent Via Courier Ontario Heritage Trust '10 Adelaide Street East Toronto, ON MsC 1J3 Re: Passage of By-law to Designate Land Registry Office 400 Centre Street South, Whitby Please be advised that the Town of Whitby Council enacted By-law # 6986-15 at its meeting held on April 20, 2015 to designate the above noted property in the Town of Whitby, as being of cultural heritage value or interest under Part lV of the Ontario Heritage Act, R.S.O. 1990, O.18, Part lV, Section 29. A copy of the Notice of Passing of the by-law, in addition to copy of By-law # 6986-15 has been attached for your reference. Further information regarding this matter may be obtained by contacting the undersioned. Sincerely, Sudan Cassel, 905-430-4300 ext.2364 i:, t_:' :.t,-. :, if r,.i f r lii--,5t-,1.:..1 SC/lam Encl. Copy. D. Wilcox, Town Clerk R. Short, Commissioner of Planning S. Ashton, Planner ll, Planning Department A. -

2017 Spring Issue of the Acorn

Spring 2017 VOLUME 42 150 REFLECTIONS ISSUE 1 WORKING COPY.indd 1 2017-04-20 7:08:57 PM Interested in hosting a future Ontario Heritage Conference? We are presently looking for communities who would be interested in hosting our Annual Ontario Heritage for future years starting with the 2019 opening. Hosting a conference is a great way to showcase your community and all the great work you do in heritage conservation. For more information and deadline please view the RFP posted on www.communityheritageontario.ca Stratford/St. Marys Ontario Heritage Conference, May 12-14, 2016 co-hosted by ACO and Community Heritage Ontario. Photos Liz Lundell WORKING COPY.indd 2 2017-04-20 7:09:01 PM CONTENTS 1 From the President by Catherine Nasmith 2 Sir John A. Macdonald Was Here by Lindi Pierce 4 Public Works in Ontario: An architectural legacy Spring by Sharon Vattay Issue 2017 6 William George Storm: Toronto’s Architect by Loryssa Quattrociocchi 8 New Province, New Farmhouses by Shannon Kyles 10 Victorian Inspiration: Yesterday’s Buildings Inspire Tomorrow’s Architects by Jacob Drung 12 Merrickville's Alloy Foundry: A landmark business older than Canada by Mark Oldeld 14 Misener House, Westeld Heritage Village by Jamie MacLean 16 Homer Ransford Watson: Renowned artist of Doon by Jean Haalboom 18 Halton Hills 150 Project: Celebrating Lucy Maud Montgomery in Norval by Patricia Farley 20 Eric Arthur and Barnum House: The founding of Architectural Conservancy Ontario by Richard Longley 22 A 150th Present for Prescott Basilica of Our by Bonita Slunder -

Call for Tender

1847 1849 1850 G00001 G00006 G00013 Jan. 6, 1847 Jan. 24, 1849 Feb. 7, 1850 Page 3 Page 3 Page 67 Architect: J.G. Howard Architect: F.W. Cumberland Architect: no architect Tender: Jan. 12, 1847 Tender: Feb. 6, 1849 Tender: Feb. 18, 1850 Detail: Two, cut-stone-fronted ware- Detail: Prison, attached to Gore District Detail: Repairs to Queen’s Wharf, To- houses, Yonge St., adjoining Bank of British Jail & Court House, Hamilton ronto North America (for A.V. Brown,- see ad Dec.29/47 re: A.V. Brown & Co. [grocers] G00007 G00014 having moved into this new building). Feb 7, 1849 Apr. 9, 1850 Page 3 Page 171 G00002 Architect: J. G. Howard Architect: Cumberland & Ridout Apr. 7, 1847 Tender: Feb 14, 1849 Tender: May 10, 1850 Page 3 Detail: Brick store, Church St. Detail: Haldimand County Buildings, Architect: no architect Cayuga Tender: Apr. 22, 1847 G00008 Detail: New Talbot District Jail and altera- Feb. 14, 1849 G00015 tions to Court House, Simcoe Page 3 Oct. 31, 1850 Architect: F.W. Cumberland Page 523 G00003 Tender: Feb. 26, 1849 Architect: no architect Jul. 24, 1847 Detail: Fireproof District Registry, altera- Tender: Nov. 14, 1850 Page 3 tions & fireproof vaults in District Court Detail: Arched cellars & markets in rear of Architect: Wm. Thomas House & alterations to District Prison, City Hall Tender: Jul. 30, 1847 Toronto Detail: Knox’s Church, Toronto-west side G00016 of Yonge St. between Richmond & Queen G00009 Nov. 16, 1850 Sts., cornerstone laid Sep. 21/47, - see Tele. Jul. 24, 1849 Page 551 Feb. 26/47, p.8. -

Heritage Churches in the Niagara Region: an Essay on the Interpretation of Style Malcolm Thurlby

Document generated on 10/01/2021 10:07 p.m. Journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada Le Journal de la Société pour l'étude de l'architecture au Canada Heritage Churches in the Niagara Region: An Essay on the Interpretation of Style Malcolm Thurlby Volume 43, Number 2, 2018 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1058039ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1058039ar See table of contents Publisher(s) SSAC-SEAC ISSN 2563-8696 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Thurlby, M. (2018). Heritage Churches in the Niagara Region: An Essay on the Interpretation of Style. Journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada / Le Journal de la Société pour l'étude de l'architecture au Canada, 43(2), 67–95. https://doi.org/10.7202/1058039ar Copyright © SSAC-SEAC, 2019 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ ANALYSIS | ANALYSE HERITAGE CHURCHES IN THE NIAGARA REGION: AN ESSAY ON THE INTERPRETATION OF STYLE1 MALCOLM THURLBY, PH.D., F.S.A., teaches MALCOLM THURLBY art and architectural history at York University, Toronto. His research concentrates on Romanesque and Gothic architecture and sculpture from the eleventh to the thirteenth century, and nineteenth-century Canadian his paper is an expanded ver- architecture. -

Royal Architectural Institute of Canada

ROYAL ARCHITECTURAL INSTITUTE OF CANADA OFFICERS PRESIDENT . A. J. HAZELGROVE (F) FIRST VI CE-PRESIDENT • • MURRAY BROWN (F) SECOND VICE-PRESIDENT . H. H. SIMMONDS HONORARY SECRETARY . JAS. H. CRAIG (F) HONORARY TREASURER J. ROXBURGH SMITH (F) PAST-PRESIDENT • CHAS . DAVID (F) SECRETARY . MISS MARY l. BILTON 1323 Boy Street, Toronto COUNCIL H. H. SIMMONDS, F. L TOWNLEY, HENRY WHITTAKER British Columbia M. C. DEWAR, G. K. WYNN • . Alberto FRANK J. MARTIN, JOHN C. WEBSTER Saskotchewon G. LESLI E RUSSEll, J. A. RUSSELL, ERIC W. THRIFT Manitoba Ontario VICTOR J. BLACKWEll (F), MURRAY BROWN (F), JAS. H. CRAIG (F), A. J. HAZELGROVE (F), D. E. KERTLAND, R. S. MORRIS (F), FORSEY PAGE (F), W. BRUCE RIDDEll (F), HARLAND STEELE (F), Quebec L. N. AUDET (F), OSCAR BEAULE (F), R. E. BOSTROM (F), HAROLD LAWSON (F) J. C. MEADOWCROFT, A. J. C. PAINE (F), MAUR ICE PAYETTE (F), J. ROXBURGH SMITH (F) D. W. JONSSON, H. ClAIRE MOTT (F) New Brunswick lESLIE R. FAIRN (F), A. E. PRIEST . Nova Scotia EDITORIAL BOARD REPRESENTATIVES British Columbia: FRED LASSERRE, Chairman; R. A. D. BERWICK, WilLIAM FREDK. GARDINER (F), R. R. McKEE, PETER THORNTON, JOHN WADE Alberta : C. S. BURGESS (F), Chairman; M. C. DEWAR, MARY l . IMRIE, PETER L RULE Saska tchewan: H. K. BlACK, Cha irman; F. J. MART IN, DAN H. STOCK, JOHN C. WEBSTER Manitoba : J. A. RUSSEll, Chairman; H. H. G. MOODY, ERIC THRIFT Ontario: JAS. A. MURRAY, Cha irman; AlAN ARMSTRONG, WATSON 8AlHARRIE, L. Y. MciNTOSH, ALVI N R. PRACK, HARRY P. SMITH, A. B. SCOTT, J. B. SUTTON , PETER Tlll.MAN, WILLIAM WATSON Q uebec : RICHARD E. -

What Is a Genealogist to Do When He/She Reads Statements in Popular

28 Apr.1850 28 M.y 1850 61un.1850 Sarah Henry 31ul.l850 Ann 24 May 1850 Hannah Richard 51ul.l850 Jane 13Iun.---- Ann Jane Joseph What is a genealogist to do when he/she reads statements in popular and 18 Sep.1850 16 Apr.1850 respected publications crediting another person with an achievement that we 17 Sep.1850 know proudly belongs to a relative? What if such statements are often writ- 20 lul.l 850 18 Sep.1850 ten as absolute fact, yet contradictory to our own family history? What if 22 Apr.1850 Amelia George every time one picks up a book or reads a magazine article about the subject 211ul.l850 Charlone 20 lul.l 850 Sarah John East in question, that glaring "mistake" is found? One might try to ignore them. 26 Sep.1850 Jane Gwilliambury But most family historians would do as much as possible to correct such in- 30 Apr.1850 Frederick Joseph Whitchurch IOcI.1850 accuracies. I was caught in just such a problem in the Spring and Summer of 12 Feb. 1850 1986. In my case the inaccuracy was a fully understandable case of mistaken 70cI.1850 II Nov.1845 identity. But because it appeared in print again and again, I grew increasing- ly frustrated. I decided to try to set the record straight. 29 M.y 1850 281ul.l850 It has always been the contention in our family that my maternal great- 20 Jun.1850 13 Ocl.1850 great-great uncle, a Welsh stonemason and master builder named Charles IOcI.I850 Thomas Thomas (1820-1867) executed the beautiful sandstone carvings on 270cI.1850 Victoria Hall in the town of Cobourg, Ontario.