Categorizing Morality Systems Through the Lens of Fallout

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wasteland: the Apocalyptic Edition: Volume 3 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

WASTELAND: THE APOCALYPTIC EDITION: VOLUME 3 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Christopher J. Mitten,Remington Veteto,Brett Weldele,Justin Greenwood,Sandy Jarrell,Antony Johnston | 344 pages | 05 Nov 2013 | Oni Press,US | 9781620100936 | English | Portland, United States Wasteland: The Apocalyptic Edition: Volume 3 PDF Book Download as PDF Printable version. Konto und Website. Schau dir unsere Richtlinien an. There are no discussion topics on this book yet. But where Fallout's world seems to have sprung from the late '50s, Wasteland 's setting branches out from somewhere in the '80s. Report incorrect product information. This edit will also create new pages on Comic Vine for:. Sidenote, the book quality by Omni is very good; strong binding and thick pages. You also don't have to match your character's vocal gender with their visual gender—I accidentally created a female melee tank with a very, very male voice and didn't realize it until an hour or two in the game. The Outside. Bleib mit Freunden in Kontakt. If you aren't rocking a fast SSD, you're in for a very long wait each time you load a saved game, or transition from one zone to the next. Andrew rated it really liked it Jan 12, Eine Auswahl grandioser Spiele, von aktuellen Hits bis zu zeitlosen Klassikern, die man auf keinen Fall verpassen sollte. Email jim. Keine Bewertungen vorhanden mit den aktiven Filtern. Newuser6 rated it really liked it Oct 04, Use your keyboard! His brand-new follow-on in the Wastelands series, The New Apocalypse, continues this tradition. Many words and phrases from our own time have changed to fit the world of Wasteland , and writer Antony Johnston has stated in interviews that the comic's language is carefully constructed. -

Fallout: Brotherhood of Steel Sourcebook

Fallout: Brotherhood of Steel sourcebook 1. History 1.1 Rebellion at the Mariposa base 1.2 Nuclear armageddon 1.3 Arrival at the Lost Hill Bunker 1.4 The birth of the Brotherhood 1.5 The mutant threat 1.6 The brotherhood is split in two 1.7 The coming of the Enclave 1.8 The western brotherhood today 2. The western brotherhood 2.1 Organisation 2.2 Recruiting 2.3 Culture 2.4 Economics 2.5 Logistics 2.6 Spheres of influence 3. The eastern brotherhood 3.1 History 3.2 Recruiting 3.3 Culture 3.4 Economics 3.5 Logistics 3.6 Spheres of influence 4. Personalities 4.1 Historical personalities Roger Maxson Marion Vree Simon Barnaky 4.2 Current personalities Jared Arnson Brent Anchor Daryl Mckenzie 5. Traits 6. Brotherhood rank table 6.1 Western brotherhood 6.2 Eastern brotherhood 7. Perks 7.1 Perks available to both the western and eastern brotherhood 7.2 Perks available to the western brotherhood 7.3 Perks available to the eastern brotherhood 8. Vehicles 8.1 “Steel Eagle” Vertibird 8.2 Airship 8.3 APC 8.4 Scouter 9. The brotherhood in games 9.1 Incorporating the brotherhood in campaigns 9.2 Playing a brotherhood Player-Character 9.3 Playing brotherhood NPCs Introduction This document is intended as a source of information for players who are including the brotherhood in their campaign, or are playing brotherhood characters. Much of the information in this document is totally unofficial and original, due to a lack of good official information about the brotherhood, and you may not agree with everything in this document (in which case you are of course free to change it to your hearts content). -

Fallout Wastelands: a Post-Nuclear Role-Playing Game

Fallout Wastelands: A Post-Nuclear Role-Playing Game A Black Diamond Project - Version 1.3 Based on Retropocalypse by David A. Hill Jr, which in turn was based on Old School Hack by 1 Kirin Robinson Page Table of Contents 3… A Few Notes About Fallout Wastelands 66... Vehicles 5… Introduction and Setup 70… Item Costs 7... Character Creation 71… Encumbrance 12... Backgrounds 72... Combat Rules 13... Brotherhood of Steel Initiate 72... Initiative and Actions 16… Courier 74... Attack, Defense, and Damage Resistance 18... Deathclaw 76... Healing and Injury 20... Enclave Remnant 77... Adventuring 22... Ghoul 77... Environments and Arenas 24... Raider 80... Karma 26... Robot 83... Leveling Up 28... Scientist 84... Overseer's Guide 30... Settler 84... Specialty Items 32... Super Mutant 90... Harder, Better, Stronger, Faster 34... Tribal 92... Additional Traits 36... Vault Dweller 97... Creating NPCs 38... Wastelander 97... Creating Encounters 40... Skills 99... Cap Rewards 46... Perks 100... Bestiary 57... Items and Equipment 116... Character Sheet 57... Weapons 118... Version Notes 61... Armor 119... Credits 63... Tools 2 Page Section 1. A Few Notes About Fallout Wastelands For years I've loved playing the Fallout games, specifically Fallout 3 and Fallout: New Vegas since I didn't have access to a computer for gaming (I am working my way through the original Fallout presently!). I became enamored by the setting and fell in love with the 50s retro-futuristic atmosphere, the pulpy Science! themes, and the surprisingly beautiful, post-apocalyptic world that unfolded before me. It was like Firefly meeting Mad Max meeting Rango and it was perfect. -

Frustrated Redemption: Patterns of Decay and Salvation in Medieval Modernist Literature

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2013 Frustrated Redemption: Patterns of Decay and Salvation in Medieval Modernist Literature Shayla Frandsen CUNY City College of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/519 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Frustrated Redemption: Patterns of Decay and Salvation in Medieval and Modernist Literature Shayla Frandsen Thesis Advisor: Paul Oppenheimer Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts of the City College of the City University of New York Table of Contents Preface 1 The Legend of the Fisher King and the Search for the 5 Modern Grail in The Waste Land, Paris, and Parallax “My burden threatens to crush me”: The Transformative Power 57 of the Hero’s Quest in Parzival and Ezra Pound’s Hugh Selwyn Mauberley Hemingway, the Once and Future King, 101 and Salvation’s Second Coming Bibliography 133 Frandsen 1 Preface “The riddle of the Grail is still awaiting its solution,” Alexander Krappe writes, the “riddle” referring to attempts to discover the origin of this forever enigmatic object, whether Christian or Folkloric,1 yet “one thing is reasonably certain: the theme of the Frustrated Redemption” (18).2 Krappe explains that the common element of the frustrated redemption theme is “two protagonists: a youth in quest of adventures and a supernatural being . -

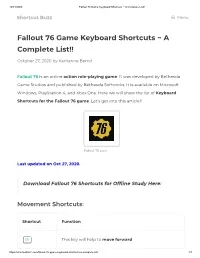

Fallout 76 Game Keyboard Shortcuts ~ a Complete List!!

10/31/2020 Fallout 76 Game Keyboard Shortcuts ~ A Complete List!! Shortcut Buzz Menu Fallout 76 Game Keyboard Shortcuts ~ A Complete List!! October 27, 2020 by Katharine Bernd Fallout 76 is an online action role-playing game. It was developed by Bethesda Game Studios and published by Bethesda Softworks. It is available on Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 4, and Xbox One. Here we will show the list of Keyboard Shortcuts for the Fallout 76 game. Let’s get into this article!! Fallout 76 Logo Last updated on Oct 27, 2020. Download Fallout 76 Shortcuts for Ofine Study Here: Movement Shortcuts: Shortcut Function W This key will help to move forward https://shortcutbuzz.com/fallout-76-game-keyboard-shortcuts-a-complete-list/ 1/7 10/31/2020 Fallout 76 Game Keyboard Shortcuts ~ A Complete List!! Shortcut Function S It is used to move back A This shortcut key will help to move left D It will move right Left Shift This key will help to sprint Alt It is used to hold the Melee/Power attack/Grenade C This shortcut key helps to run X It will move automatically Caps Lock This key will toggle always run V It will toggle 1st/ 3rd person point of view Left Ctrl It helps Crouch T This key will wait (the character must be seated) Helps to look https://shortcutbuzz.com/fallout-76-game-keyboard-shortcuts-a-complete-list/ 2/7 10/31/2020 Fallout 76 Game Keyboard Shortcuts ~ A Complete List!! Action Shortcuts: Shortcut Function Space This key will helps to jump It will attack It is used to Aim/ Block Q This helps to V.A.T.S (Automatic killing system) E It is used -

Fallout Wastelands: a Post-Atomic Role-Playing Game

Fallout Wastelands: A Post-Atomic Role-Playing Game A Black Diamond Project - Version 1.3 Based on Retropocalypse by David A. Hill Jr, which in turn was based on Old School Hack by 1 Kirin Robinson Page Table of Contents 3… A Few Notes About Fallout Wastelands 63... Tools 5… Introduction and Setup 66… Encumbrance 7... Character Creation 67... Combat Rules 12... Backgrounds 67... Initiative and Actions 13... Brotherhood of Steel Initiate 69... Attack, Defense, and Damage Reduction 16… Courier 71.. Healing and Injury 18... Deathclaw 72... Adventuring 20... Enclave Remnant 72... Environments and Arenas 22... Ghoul 75... Karma 24... Raider 78... Leveling Up 26... Robot 79... Overseer's Guide 28... Scientist 79... Specialty Items 30... Settler 85... Harder, Better, Stronger, Faster 32... Super Mutant 86... Additional Traits 34... Tribal 91... Creating NPCs 36... Vault Dweller 91... Creating Encounters 38... Wastelander 93... Cap Rewards 40... Skills 94... Bestiary 46... Perks ##... Character Sheet 57... Items and Equipment ##... Version Notes 57... Weapons ##... Credits 61... Armor 2 Page Section 1. A Few Notes About Fallout Wastelands For years I've loved playing the Fallout games, specifically Fallout 3 and Fallout: New Vegas since I didn't have access to a computer for gaming. I became enamored by the setting and fell in love with the 50s retro-futuristic atmosphere, the pulpy Science! themes, and the surprisingly beautiful, post- apocalyptic world that unfolded before me. It was like Firefly meeting Mad Max meeting Rango and it was perfect. Once I finished Fallout 3 and moved on to New Vegas I began searching for a tabletop version of Fallout so I could explore the Wasteland with my friends at college. -

Romance Never Changes…Or Does It?: Fallout, Queerness, and Mods

Romance Never Changes…Or Does It?: Fallout, Queerness, and Mods Kenton Taylor Howard University of Central Florida UCF Center for Emerging Media 500 W Livingston St. Orlando, FL 32801 [email protected] ABSTRACT Romance options are common in mainstream games, but since games have been criticized for their heteronormativity, such options are worth examining for their contribution to problematic elements within gaming culture. The Fallout series suffers from many of these issues; however, recent games in the can be modded, offering fans a way to address these problems. In this paper, I examine heteronormative elements of the Fallout series’ portrayal of queerness to demonstrate how these issues impacted the series over time. I also look more specifically at heteronormative mechanics and visuals from Fallout 4, the most recent single-player game in the series. Finally, I discuss three fan-created mods for Fallout 4 that represent diverse approaches to adding queer elements to the game. I argue that one effective response to problematic portrayals of queerness in games is providing modding tools to the fans so that they can address issues in the games directly. Keywords Mods, Modding, Queer Game Studies, Representation, Romance, Fallout INTRODUCTION Romance options are common in videogames: players can interact with non-player characters in flirtatious ways and have sex, form relationships, or even get married to those characters. Since mainstream games have been criticized for their heteronormativity by including elements that suggest “queerness is just a different twist on non-queer heterosexuality” (Lauteria 2012, 2), such options are worth examining for their contribution to problematic elements within gaming culture. -

Fallout New Vegas Pipboy Modsl

Fallout New Vegas Pipboy Modsl Fallout New Vegas Pipboy Modsl 1 / 3 2 / 3 Paying homage to the early Fallout games, the Pipboy 3500 retexture combines the classic style of the Pipboy 2000 with Fallout 3/New Vegas' Pipboy 3000 to .... Команда работающая над полным переносом New Vegas на движок и механику Fallout 4, опубликовали новое небольшое геймплейное .... New Pip-Boy 2000 Mk VI with custom scratch-made meshes, textures and working clock like in Fallout 76. Share. Requirements .... This is used to add any mods possessed to the weapon they are intended for. ... In Fallout: New Vegas, the Pip-Boy reserves the up-directional/number key 2 .... Hi guys, I really wanted to know if there are any mods to change how the pipboy looks, or maybe if there is a mod where it can add a few things .... User D_Braveheart uploaded this Fallout - Fallout 4 Fallout Pip-Boy Fallout: New Vegas Fallout 3 Nexus Mods PNG image on August 11, 2017, 1:00 pm.. For Fallout: New Vegas on the PC, a GameFAQs message board ... as tried reinstalling both mods but my pip boy still seems to have a mind of .... This useful little mod for the Fallout New Vegas game removes the gloves which appear on your hand.. I've been meaning to try out some UI/HUD mods just haven't got around to it yet. You could try using imgur and post the pic that way. April 9, 2015 .... Jump to Fallout New Vegas Mods - Fallout New Vegas Mods. The Pip- Boy 1.0 is the earliest known functioning model of the Personal Information Processor. -

Inside the Video Game Industry

Inside the Video Game Industry GameDevelopersTalkAbout theBusinessofPlay Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman Downloaded by [Pennsylvania State University] at 11:09 14 September 2017 First published by Routledge Th ird Avenue, New York, NY and by Routledge Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business © Taylor & Francis Th e right of Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman to be identifi ed as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections and of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act . All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice : Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identifi cation and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Names: Ruggill, Judd Ethan, editor. | McAllister, Ken S., – editor. | Nichols, Randall K., editor. | Kaufman, Ryan, editor. Title: Inside the video game industry : game developers talk about the business of play / edited by Judd Ethan Ruggill, Ken S. McAllister, Randy Nichols, and Ryan Kaufman. Description: New York : Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa Business, [] | Includes index. Identifi ers: LCCN | ISBN (hardback) | ISBN (pbk.) | ISBN (ebk) Subjects: LCSH: Video games industry. -

Mba Canto C 2019.Pdf (3.357Mb)

The Effect of Online Reviews on the Shares of Video Game Publishing Companies Cesar Alejandro Arias Canto Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Business Administration (MBA) in Finance at Dublin Business School Supervisor: Richard O’Callaghan August 2019 2 Declaration I declare that this dissertation that I have submitted to Dublin Business School for the award of Master of Business Administration (MBA) in Finance is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated, where it is clearly acknowledged by references. Furthermore, this work has not been submitted for any other degree. Signed: Cesar Alejandro Arias Canto Student Number: 10377231 Date: June 10th, 2019 3 Acknowledgments I would like to thank all the lecturers whom I had the opportunity to learn from. I would like to thank my lecturer and supervisor, Richard O’Callaghan. One of the best lecturers I have had throughout my education and a great person. I would like to thank my parents and family for the support and their love. 4 Contents Table of Contents Declaration ................................................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgments ...................................................................................................................... 3 Contents ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Tables and figures index .......................................................................................................... -

Gurps: Fallout

GURPS: FALLOUT by VARIOUS AUTHORS compiled, EDITED AND UPDATED BY Nathan Robertson GURPS Fallout by VARIOUS AUTHORS compiled, EDITED AND UPDATED BY Nathan Robertson GURPS © 2008 – Steve Jackson Games Fallout © 2007 Bethesda Softworks LLC, a ZeniMax Media company All Rights Reserved 2 Table of Contents PART 1: CAMPAIGN BACKGROUND 4 Chapter 1: A Record of Things to Come 5 Chapter 2: The Brotherhood of Steel 6 Chapter 3: The Enclave 9 Chapter 4: The Republic of New California 10 Chapter 5: The Vaults 11 Chapter 6: GUPRS Fallout Gazetteer 12 Settlements 12 Ruins 17 Design Your Own Settlement! 18 Chapter 7: Environmental Hazards 20 PART 2: CHARACTER CREATION 22 Chapter 8: Character Creation Guidelines for the GURPS Fallout campaign 23 Chapter 9: Wasteland Advantages, Disadvantages and Skills 27 Chapter 10: GURPS Fallout Racial Templates 29 Chapter 11: GURPS Fallout Occupational Templates 33 Fallout Job Table 34 Chapter 12: Equipment 36 Equipment 36 Vehicles 42 Weapons 44 Armor 52 Chapter 13: A Wasteland Bestiary 53 PART 3: APPENDICES 62 Appendix 1: Random Encounters for GURPS Fallout 63 Appendix 2: Scavenging Tables For GURPS Fallout 66 Appendix 3: Sample Adventure: Gremlins! 69 Appendix 4: Bibliography 73 3 Part 1: Campaign Background 4 CHAPTER 1: A Record of Things to Eventually, though, the Vaults opened, some at pre-appointed times, Come others by apparent mechanical or planning errors, releasing the inhabitants to mix with surface survivors in a much-changed United States, It’s all over and I’m standing pretty, in the dust that was a city. on a much-changed planet Earth: the setting for Fallout Unlimited. -

Loot Crate and Bethesda Softworks Announce Fallout® 4 Limited Edition Crate Exclusive Game-Related Collectibles Will Be Available November 2015

Loot Crate and Bethesda Softworks Announce Fallout® 4 Limited Edition Crate Exclusive Game-Related Collectibles Will Be Available November 2015 LOS ANGELES, CA -- (July 28th, 2015) -- Loot Crate, the monthly geek and gamer subscription service, today announced their partnership today with Bethesda Softworks® to create an exclusive, limited edition Fallout® 4 crate to be released in conjunction with the game’s worldwide launch on November 10, 2015 for the Xbox One, PlayStation® 4 computer entertainment system and PC. Bethesda Softworks exploded hearts everywhere when they officially announced Fallout 4 - the next generation of open-world gaming from the team at Bethesda Game Studios®. Following the game’s official announcement and its world premiere during Bethesda’s E3 Showcase, Bethesda Softworks and Loot Crate are teaming up to curate an official specialty crate full of Fallout goods. “We’re having a lot of fun working with Loot Crate on items for this limited edition crate,” said Pete Hines, VP of Marketing and PR at Bethesda Softworks. “The Fallout universe allows for so many possibilities – and we’re sure fans will be excited about what’s in store.” "We're honored to partner with the much-respected Bethesda and, together, determine what crate items would do justice to both Fallout and its fans," says Matthew Arevalo, co-founder and CXO of Loot Crate. "I'm excited that I can FINALLY tell people about this project, and I can't wait to see how the community reacts!" As is typical for a Loot Crate offering, the contents of the Fallout 4 limited edition crate will remain a mystery until they are delivered in November.