Perryscope 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Depart..Nt at Librarllwlhlp Dectl.Ber 1974

SCIENCE FICTION I AN !NTRCIlUCTION FOR LIBRARIANS A Thes1B Presented to the Depart..nt at LibrarllWlhlp hpor1&, KaM.., state College In Partial ll'u1f'lllJlent at the Require..nte f'ar the Degrlle Muter of' L1brartlUlllhlp by Anthony Rabig . DeCtl.ber 1974 i11 PREFACE This paper is divided into five more or less independent sec tions. The first eX&lll1nes the science fiction collections of ten Chicago area public libraries. The second is a brief crttical disOUBsion of science fiction, the third section exaaines the perforaance of SClltl of the standard lib:rary selection tools in the area.of'Ulcience fiction. The fourth section oona1ats of sketches of scae of the field's II&jor writers. The appendix provides a listing of award-w1nD1ng science fio tion titles, and a selective bibli-ography of modem science fiction. The selective bibliogmphy is the author's list, renecting his OIfn 1m000ledge of the field. That 1m000ledge is not encyclopedic. The intent of this paper is to provide a brief inU'oduction and a basic selection aid in the area of science fiction for the librarian who is not faailiar With the field. None of the sections of the paper are all-inclusive. The librarian wishing to explore soience fiction in greater depth should consult the critical works of Damon Knight and J&Iles Blish, he should also begin to read science fiction magazines. TIlo papers have been Written on this subject I Elaine Thomas' A Librarian's .=.G'="=d.::.e ~ Science Fiction (1969), and Helen Galles' _The__Se_l_e_c tion 2!. Science Fiction !2!: the Public Library (1961). -

Nebula Awards Showcase 2012

an imprint of Prometheus Books Amherst, NY Published 2012 by Pyr®, an imprint of Prometheus Books Nebula Awards Showcase 2012. Copyright © 2012 by Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA, Inc.). All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or conveyed via the Internet or a website without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations em- bodied in critical articles and reviews. Cover illustration © Michael Whelan Cover design by Grace M. Conti-Zilsberger Inquiries should be addressed to Pyr 59 John Glenn Drive Amherst, New York 14228–2119 VOICE: 716–691–0133 FAX: 716–691–0137 WWW.PYRSF.COM 16 15 14 13 12 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nebula Awards showcase 2012 / edited by James Patrick Kelly and John Kessel. p. cm. ISBN 978–1–61614–619–1 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978–1–61614–620–7 (ebook) 1. Science fiction, American. I. Kelly, James P. (James Patrick) II. Kessel, John. PS648.S3A16 2012 813'.0876208—dc23 2012000382 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper PERMISSIONS “Ponies,” copyright 2010 by Kij Johnson, first published on Tor.com, January 2010. “The Sultan of the Clouds,” copyright 2010 by Geoffrey Landis, first published in Asimov’s Sci- ence Fiction, September 2010. “Map of Seventeen,” copyright 2010 by Christopher Barzak, first published in The Beastly Bride: Tales of the Animal People, edited by Ellen Datlow and Terry Windling, Viking. -

Tor.Com, Which Averages 1 Million Unique Visitors and 3 Million Pageviews Per Month, with

TORDOTCOM JULY 2021 A Psalm for the Wild-Built Becky Chambers Just when the world needs it comes a story of kindness and hope from one of the masters of Hopepunk Hugo Award-winner Becky Chambers's delightful new series gives us hope for the future. It's been centuries since the robots of Panga gained self-awareness and laid down their tools; centuries since they wandered, en masse, into the wilderness, never to be seen again; centuries since they faded into myth and urban legend. One day, the life of a tea monk is upended by the arrival of a robot, there to honor the old promise of checking in. The robot cannot go back until the question of "what do people need?" is answered. FICTION / SCIENCE FICTION / ACTION & ADVENTURE But the answer to that question depends on who you ask, and how. Tordotcom | 7/13/2021 They're going to need to ask it a lot. 9781250236210 | $20.99 / $28.99 Can. Hardcover with dust jacket | 160 pages | Carton Qty: 28 8 in H | 5 in W Becky Chambers's new series asks: in a world where people have what they Other Available Formats: want, does having more matter? Ebook ISBN: 9781250236227 Audio ISBN: 9781250807748 PRAISE "This was an optimistic vision of a lush, beautiful world that came back from the brink of disaster. Exploring it with the two main characters was a fun and MARKETING -Long-term support for Hugo Award fascinating experience.” —Martha Wells winner Becky Chambers’ Monk & Robot series, including consumer & industry mailings & advertising targeting existing "I'm the world's biggest fan of odd couple buddy road trips in science fiction, and fans & readers of hopeful science fiction this odd couple buddy road trip is a delight: funny, thoughtful, touching, sweet, and one of the most humane books I've read in a long time. -

JUDITH MERRIL-PDF-Sep23-07.Pdf (368.7Kb)

JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. Works by Merril include a variety of types and modes—pieces she wrote at Morris High School in the Bronx, newsletters and fanzines she edited; sports, westerns, and detective fiction and non-fiction published in pulp magazines up to 1950; science fiction stories, novellas, and novels; book reviews; critical essays; edited anthologies; and both audio and video recordings of her fiction and non-fiction. Works about Merill cover over six decades, beginning shortly after her first science fiction story appeared (1948) and continuing after her death (1997), and in several modes— biography, news, critical commentary, tribute, visual and audio records. This new online bibliography updates and expands the primary bibliography I published in 2001 (Elizabeth Cummins, “Bibliography of Works by Judith Merril,” Extrapolation, vol. 42, 2001). It also adds a secondary bibliography. However, the reasons for producing a research- based Merril bibliography have been the same for both publications. Published bibliographies of Merril’s work have been incomplete and often inaccurate. -

The Multidimensional Guide to Science Fiction and Fantasy of the Twentieth Century, Volume 1

THE MULTIDIMENSIONAL GUIDE TO SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY, VOLUME 1 EDITED BY NAT TILANDER 2 Copyright © 2010 by Nathaniel Garret Tilander All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted by any means—whether auditory, graphic, mechanical, or electronic—without written permission of both publisher and author, except in the case of brief excerpts used in critical articles and reviews. Unauthorized reproduction of any part of this work is illegal and is punishable by law. Cover art from the novella Last Enemy by H. Beam Piper, first published in the August 1950 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, and illustrated by Miller. Image downloaded from the ―zorger.com‖ website which states that the image is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain License. Additional copyrighted materials incorporated in this book are as follows: Copyright © 1949-1951 by L. Sprague de Camp. These articles originally appeared in Analog Science Fiction. Copyright © 1951-1979 by P. Schuyler Miller. These articles originally appeared in Analog Science Fiction. Copyright © 1975-1979 by Lester Del Rey. These articles originally appeared in Analog Science Fiction. Copyright © 1978-1981 by Spider Robinson. These articles originally appeared in Analog Science Fiction. Copyright © 1979-1999 by Tom Easton. These articles originally appeared in Analog Science Fiction. Copyright © 1950-1954 by J. Francis McComas. These articles originally appeared in Fantasy and Science Fiction. Copyright © 1950-1959 by Anthony Boucher. These articles originally appeared in Fantasy and Science Fiction. Copyright © 1959-1960 by Damon Knight. These articles originally appeared in Fantasy and Science Fiction. -

February 2021

F e b r u a r y 2 0 2 1 V o l u m e 1 2 I s s u e 2 BETWEEN THE PAGES Huntsville Public Library Monthly Newsletter Learn a New Language with the Pronunciator App! BY JOSH SABO, IT SERVICES COORDINATOR According to Business Insider, 80% of people fail to keep their New Year’s resolutions by the second week in February. If you are one of the lucky few who make it further, congratulations! However, if you are like most of us who have already lost the battle of self-improvement, do not fret! Learning a new language is an excellent way to fulfill your resolution. The Huntsville Public Library offers free access to a language learning tool called Pronunciator! The app offers courses for over 163 different languages and users can personalize it to fit their needs. There are several different daily lessons, a main course, and learning guides. It's very user-friendly and can be accessed at the library or from home on any device with an internet connection. Here's how: 1) Go to www.myhuntsvillelibrary.com and scroll down to near the bottom of the homepage. Click the Pronunciator link below the Pronunciator icon. 2) Next, you can either register for an account to track your progress or simply click ‘instant access’ to use Pronunciator without saving or tracking your progress. 3) If you want to register an account, enter a valid email address to use as your username. 1219 13th Street Then choose a password. Huntsville, TX 77340 @huntsvillelib (936) 291-5472 4) Now you can access Pronunciator! Monday-Friday Huntsville_Public_Library 10 a.m. -

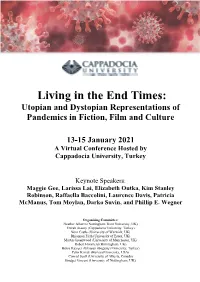

Living in the End Times Programme

Living in the End Times: Utopian and Dystopian Representations of Pandemics in Fiction, Film and Culture 13-15 January 2021 A Virtual Conference Hosted by Cappadocia University, Turkey Keynote Speakers: Maggie Gee, Larissa Lai, Elizabeth Outka, Kim Stanley Robinson, Raffaella Baccolini, Laurence Davis, Patricia McManus, Tom Moylan, Darko Suvin, and Phillip E. Wegner Organising Committee: Heather Alberro (Nottingham Trent University, UK) Emrah Atasoy (Cappadocia University, Turkey) Nora Castle (University of Warwick, UK) Rhiannon Firth (University of Essex, UK) Martin Greenwood (University of Manchester, UK) Robert Horsfield (Birmingham, UK) Burcu Kayışcı Akkoyun (Boğaziçi University, Turkey) Pelin Kıvrak (Harvard University, USA) Conrad Scott (University of Alberta, Canada) Bridget Vincent (University of Nottingham, UK) Contents Conference Schedule 01 Time Zone Cheat Sheets 07 Schedule Overview & Teams/Zoom Links 09 Keynote Speaker Bios 13 Musician Bios 18 Organising Committee 19 Panel Abstracts Day 2 - January 14 Session 1 23 Session 2 35 Session 3 47 Session 4 61 Day 3 - January 15 Session 1 75 Session 2 89 Session 3 103 Session 4 119 Presenter Bios 134 Acknowledgements 176 For continuing updates, visit our conference website: https://tinyurl.com/PandemicImaginaries Conference Schedule Turkish Day 1 - January 13 Time Opening Ceremony 16:00- Welcoming Remarks by Cappadocia University and 17:30 Conference Organizing Committee 17:30- Coffee Break (30 min) 18:00 Keynote Address 1 ‘End Times, New Visions: 18:00- The Literary Aftermath of the Influenza Pandemic’ 19:30 Elizabeth Outka Chair: Sinan Akıllı Meal Break (60 min) & Concert (19:45-20:15) 19:30- Natali Boghossian, mezzo-soprano 20:30 Hans van Beelen, piano Keynote Address 2 20:30- 22:00 Kim Stanley Robinson Chair: Tom Moylan Follow us on Twitter @PImaginaries, and don’t forget to use our conference hashtag #PandemicImaginaries. -

SUMMER 1981 Vol

m $3.00 x -t SUMMER1981 Vol. 22, No. 2 XJ ,,J:a The Fantastic Stories of 0 Cornell Woolrich r Edited by Charles G. Waugh and Martin H. J:a Greenberg. Introduction by Francis M . Nevins, Jr. -t Afterword by Barry M. Malzberg. Alfred Hitch cock recogni zed their ee ri e potential immediately, -0 m ak ing m ovies fro m the s to ri es of Corn ell Woolrich. Tales of the utterl y lost w ith a se nse of 2 EXTRAPOLATION creeping doom as palpable as colda fingers bout the throat. $24.95 The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction April, 1965 en Edited by Edward L. Ferman. Memoirs edited by c Martin H. Greenberg. This is a fa cs imile of th e first s: iss ue o f Th e M agazine o f Fantasy and Science Fic s: tio n edited b y one o f th e acknowledged greats in m the field, Ed ward L. Ferman. Al so incl uded here are :ti specially so li cited m emoirs fro m contributors such as Poul Anderso n, Isaac Asimov, and o th ers. $16.95 Also of interest ... Astounding Science Fiction July, 1939 < Edited b y John W. Ca mpbell, Jr. Additional matter g_ edited b y M artin H. Gree nberg. Preface by Stanley Sc hmidt $12.95 The Science Fiction of Mark Clifton Ed it ed by Barry N . M alzbcrg and M art in H . Green berg. Introducti on b y Ba rry N. Malzberg $15.00 Bridges to Science Fiction Edited by George E. -

Science Fiction Hall of Fame Chosen by the Members of the Science Fiction Writers of America

Edition der SF – The Science Fiction Writers of America / SFWA Recherche: Lutz Schridde für www.sfgh.de <Recherche mit http://www.chpr.at , http://en.wikipedia.org , http://contento.best.vwh.net , http://www.locusmag.com , http://www.locusmag.com/SFAwards/Db/Nebula.html und eigener Bibliothek> The Science Fiction Hall of Fame chosen by the members of The Science Fiction Writers of America Robert Silverberg (Ed.) - Science Fiction Hall of Fame 1 (USA 1970, 2003) Ben Bova (Ed.) - Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Bd. 2A (USA 1973, 2005) Ben Bova (Ed.) - Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Bd. 2B (USA 1973) Zusammenfassung: (Formuliert für Volltext-Suchmaschinen) Dieses Memo zur den ersten Anthologien Science Fiction Hall of Fame 1, 2A und 2B zeigt die Präsenz der bewerteten Geschichten in deutschen Ausgaben an. Nur die Geschichte des Initiators des 1965 gegründeten Schriftstellerverbandes Science Fiction Writers of America SFWA wurde nicht in deutscher Übersetzung gefunden. Die Geschichten kennzeichnen das Qualitätsverständnis der SFWA. Dieses Verständnis von professioneller Qualität wird durch Platzierung der Geschichten in weiteren Anthologien bestätigt. Es setzte sich innerhalb des SFWA bis heute durch die Vergabe des Nebula Award fort. Der erste Herausgeber Robert Silverberg vertieft alsbald grundsätzliche Kritik am Genre, sonst bisher besonders vertreten durch Samuel Delany und Barry N. Malzberg, weitere folgen. Es zeigt sich nebenbei ein loses Subgenre von Science Fiction der Science Fiction, teils mit Selbstanwendungen gewohnter Metaphern, das die Nerven des Genres bloßlegt. Auch eine interne Genre-Satire zeigt sich, z. B. 1949 mit What mad universe von Frederic Brown und 1969-1973 mit den Autoren-Parodien des Amerikaners und Wahl-Engländers John T. -

Australian SF News 15

1979 ENDS ON ASAD NOTE The Australian Professional Scene FOR AUSTRALIAN FANS LEANNE FRAHM has sold a further two A big blow to Australian sf fandom in stories to a U.S. publication.This brings February this year was the death of RON her sales tally to four in less than a GRAHAM, but unfortunately the loss of year.'Deus Ex Corporis' will be published stalwarts in the sf field did not finish in CHRYSALIS 7,edited by Roy Torgeson for with our close friend and associate Ron . Zebra Books.The other story will appear in CHRYSALIS 8 later this year, and with JOHN RYAN whose book 'Panel by Panel' on this volume the series will be taken over the Australian comic strip was published by a hardcover publisher,Doubleday. by Cassell Australia in November last , died early in December while on a trip ROOMS OF PARADISE, the all-original anth- to Mount Isa for his company. JIM ELLIS, ogy edited by Lee Harding for Quartet, editor and publishing director with Australia ,has been the biggest-sei1ing Cassell Australia, who was responsible sf collection so far published in this for publishing science fiction and in country. The U.K.edition also sold out particular the work of Lee Harding at within the first few months of publication. Cassells,died on the 16th of December. The publishers are firm in their intention ROBERT J.McCUBBIN , a founder member that the book will NOT be remaindered and of the Melbourne SF Club passed away will be kept in print for many years to quietly on the 29th of December. -

Nr 1 Red: George Sjöberg (18 S)

Nr 1 red: George Sjöberg (18 s) 1960 Redaktionellt George Sjöberg: Det handlar om stjärnorna Recensioner av fanzines Bo Stenfors: Fanzinerecensionerna SFSF Stadgar Noveller Bo Stenfors: Hemkomst Sam J. Lundwall: Den första julnatten Nr 2 red: George Sjöberg (18 s) 1960 Redaktionellt George Sjöberg: Idealism och föreningsverksamhet Artiklar/debatt om sf Bo Stenfors: Ur SFSF:s bibliotek 1: ”A Princess of Mars” av Edgar Rice Burroughs SFSF George Sjöberg: Sunside (mötesrapport) Noveller W. F. Nolan och C. E. Fritch: Skeppet Dikter Per Lindström: Endast där George Sjöberg: homo superior Insändare Brev-Forum Alvar Appeltofft Robert Brandorf Anders S. Fröberg Karl Gustav Jakobsson Hans-Ulrik Karlén (2) Henrik Rabe Arne Sjögren Karl Karlson-Orre Åke Hansson Ingvar Svensson Nr 3 red: George Sjöberg (22 s) 1960 Redaktionellt George Sjöberg: Ledaren SFSF Förteckning över medlemmar i SFSF Affären Dahlman (om medlemsmöte) Noveller Jacob Palme: Expedition till framtiden (del 1 av 2) Insändare Brev-Forum Åke Hansson Hans-Ulrik Karlén Lars-Olov Strandberg Martin Ruong Karl Karlson-Orre Robert Brandorf Nr 4 red: George Sjöberg (24 s) 1960 Artiklar/debatt om fandom Ingvar Svensson: Distribution av fanzines (svar av red) John Baxter: Fandom i Australien (översatt och förkortad av Bo Stenfors) om övrigt Jupiter omgiven av dödligt bälte Dödsstråle har blivit verklighet Kolliderande galaxer slog hastighetsrekord Dussinet ”amerikaner” i rymden Håkan Elmqvist: I blinken (om signalfrekvens och uppmärksamhet) Recensioner av fanzines Fanzine-Forum Noveller Jacob Palme: Expedition till framtiden (del 2 av 2) Nr 5 finns ej Nr 6 red: Bo Stenfors (16 s) 1962 Redaktionellt Bo Stenfors: Redaktionsspalten Artiklar/debatt om sf Hans Eklund: Vår framtid – helvete eller paradis? Kutzen & Ceji: Modern Sf-film Sam J. -

Uncle Hugo's Science Fiction Bookstore Uncle Edgar's Mystery Bookstore 2864 Chicago Ave

Uncle Hugo's Science Fiction Bookstore Uncle Edgar's Mystery Bookstore 2864 Chicago Ave. S., Minneapolis, MN 55407 Newsletter #127 September — November, 2019 Hours: M-F 10 am to 7 pm RECENTLY RECEIVED AND FORTHCOMING SCIENCE FICTION Sat. 10 am to 6 pm; Sun. Noon to 5 pm ALREADY RECEIVED Uncle Hugo's 612-824-6347 Uncle Edgar's 612-824-9984 Fantasy & Science Fiction July / August 2019 (New fiction, reviews, more) Fax 612-827-6394 ................................................................. $8.99 E-mail: [email protected] Locus #701 June 2019 (Interviews with Michael Blumlein and Kaaron Warren; Website: www.UncleHugo.com Nebula winners; forthcoming books; industry news, reviews, and more). $8.99 Locus #702 July 2019 (Interviews with Ben H. Winters and R.F. Kuang; industry Award News news, reviews, and more)............................................. $8.99 Locus #703 August 2019 (Interviews with William Gibson and Lesley Nneka Araimah; industry news, reviews, and more). $8.99 The Nebula Award for best sf Thirteen Doctors, 13 Stories (PBO; Kids; An updated version of the popular novel of last year went to The anthology, with a brand-new story featuring the newest Doctor).. $17.99 Calculating Stars by Mary Robinette Adams, Richard The Adventures of Egg Box Dragon (Emma is delighted when her homemade Kowal ($18.99). dragon comes to life. And best of all, he is excellent at finding lost treasures).. $9.99 The Mythopoeic Award for best Bradley, Lisa M. Exile (Twenty years ago, a toxic spill in Exile, Texas, poisoned residents with permanent adult fantasy of last year went to rage. Now only folks who pass the feds' 4-S test - smart, strong, sterile, sane - can escape Spinning Silver by Naomi Novik the town's quarantine).............................................