In Search of Surrealism in Alex Van Warmerdam's Borgman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Persmap

MARC VAN WARMERDAM PRESENTEERT een film van ALEX VAN WARMERDAM Tom Dewispelaere Alex van Warmerdam Maria Kraakman Gene Bervoets Annet Malherbe Loes Haverkort Pierre Bokma Eva van de Wijdeven en Henri Garcin als Gerard SCENARIO EN REGIE ALEX VAN WARMERDAM PRODUCENT MARC VAN WARMERDAM COPRODUCENTEN EURYDICE GYSEL, KOEN MORTIER, ROBERT KIEVIT LINE PRODUCER BERRY VAN ZWIETEN DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY TOM ERISMAN NSC PRODUCTION DESIGN GEERT PAREDIS MONTAGE JOB TER BURG NCE MUZIEK ALEX VAN WARMERDAM KOSTUUMONTWERP STINE GUDMUNDSEN-HOLMGREEN MAKE-UP MARIKE WILLARD-HOOGVELD SOUND DESIGN PETER WARNIER CASTING ANNET MALHERBE I.S.M. KEMNA CASTING SCHNEIDER VS. BAX IS EEN PRODUCTIE VAN GRANIET FILM IN COPRODUCTIE MET CZAR FILM, VARA EN MOLLYWOOD www.cineart.nl /cineartnederland /CineartNL 4gt VANAF 28 MEI IN DE BIOSCOOP PERSMAP SYNOPSIS SCHNEIDER vs. BAX een film van Alex van Warmerdam Schneider, een huurmoordenaar, wordt gebeld door Mertens. Hij heeft een spoedopdracht voor Schneider, maar Schneider weigert. Hij is jarig en heeft zijn vrouw Lucy beloofd te helpen met het voorbereiden van het diner dat zij vanavond geven. Mertens benadrukt dat het belangrijk is en dat het vandaag moet gebeuren. “Het gaat om Ramon Bax, een schrijver. Hij woont alleen aan de rand van een afgelegen meer. Het is een makkelijke klus, met een beetje geluk ben je voor de middag weer thuis.” Met tegenzin gaat Schneider akkoord, maar de makkelijke klus blijkt een gecompliceerde. speelduur: 97' Voor meer informatie: land: Nederland, België Cinéart Nederland jaar: 2015 Janneke -

Job Ter Burg, Ace, Nce Film Editor

JOB TER BURG, ACE, NCE FILM EDITOR Short Biography Job ter Burg (1972, Maarn, The Netherlands) graduated from The Netherlands Film and Television Academy as a film editor (1992-1996), after two years of studying Film and Television at the University of Utrecht (1990-1992), which were preceded by grammar school in Doorn (1984-1990). He started out as an editor for mostly television documentaries, but after his continued collaboration with film school class mate Martin Koolhoven on DARK LIGHT (1997) and the much awarded SUZY Q (1999), he focused on editing feature films. After two nominations for Best Film Editing (at the yearly Dutch Film Festival in Utrecht) for his work on GODFORSAKEN (Pieter Kuijpers, 2003) and SCHNITZEL PARADISE (Martin Koolhoven, 2005), he got to be the lead film editor on the prestigious BLACK BOOK (2006), Paul Verhoeven’s first Dutch film in 20 years. Ter Burg was awarded with the ICS Award for Best Editing for Paul Verhoeven’s ELLE (2016) and with the Golden Calf for Best Film Editing for his work on Rudolf van den Berg’s TIRZA (2010). ELLE (2016) won more than 60 awards, including two Golden Globes (Best Foreign Language Film 2017 & Best Actress 2017) and was nominated for an Academy Award in the Best Actress category (Isabelle Huppert). BORGMAN (2013) and ELLE (2016) were selected for the Competition at the Festival de Cannes, BRIMSTONE (2016) and BLACK BOOK (2006) were selected for the Competition in at the Venice Film Festival. THE LAST DAYS OF EMMA BLANK (2009) won the Europa Cinemas Award at Venice Days. -

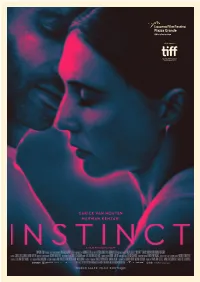

Halina Reijn's Instinct

Halina Reijn’s Instinct: Locarno, Toronto, London and NFF opener Carice on Reijn, Thrones and Red Light Doreen Boonekamp on ten years at the Film Fund Eye on Tarkovsky Previews of Cinekid and Holland Film Meeting Issue #36 September 2019 Locarno / Venice / TIFF / NFF issue Index COLOPHON 6-9 Instinctive director Halina Reijn’s 34-35 Trigger happy Joost van Hezik’s debut Instinct world-premiered at tragi-comic psycho-noir Boy Meets Gun See NL is published four times per Locarno, was selected for TIFF and world premieres at Busan year by Eye International and London, and now opens the Netherlands The Netherlands Film Fund and is distributed to international film Film Festival 36-37 Return of HFM Assessing the professionals. yearly interface between the Dutch 10-11 A piece of Carice Dutch icon production industry and the international Editors in chief: Marten Rabarts, Carice van Houten discusses Instinct, co-pro, sales and distribution sectors (Eye), Jonathan Mees (Netherlands Film Fund) Executive editor: Nick her friendship with Halina Reijn and their Cunningham Contributor: Geoffrey new production company Man Up 38-39 The kids are alright Previewing Macnab Concept & Design: Cinekid for Professionals 2019 Lava.nl Layout: def., Amsterdam 12-13 Girl talk Stefanie Kolk was back Printing: mediaLiaison Printed at Locarno with her latest short film Eyes 40-41 Kaboom time for toons on FSC paper © All rights reserved: on the Road, about three girls in a car The Netherlands has a new animation The Netherlands Film Fund and festival, based in Utrecht -

Official Selection Official Selection

Official selection Official selection TO LIVE TO SING A FILM BY HALINA REIJN WITH CARICE VAN HOUTEN, MARWAN KENZARI 2019 - NETHERLANDS - DRAMA/THRILLER - 98 MIN SUNDAY - 11/08 - 11:15 - RIALTO 1 - INDUSTRY SUNDAY - 11/08 - 21:30 - PALACINEMA 1 - PRESS MONDAY - 12/08 - 21:30 - PIAZZA GRANDE INTERNATIONAL PRESS INTERNATIONAL SALES claudiatomassini & associates Films Boutique International Film Publicity [email protected] Claudia Tomassini www.filmsboutique.com Mobile:+49 173 205 5794 [email protected] www.claudiatomassini.com CREW DIRECTOR Halina Reijn SCREENPLAY Esther Gerritsen, Halina Reijn DOP Jasper Wolf PRODUCTION DESIGN Lieke Scholman EDITOR Job ter Burg COSTUME DESIGN Minke Lunter HAIR AND MAKE-UP Gerda Koekoek COMPOSER Ella van der Woude 1ST AD Philip de Iongh, Willem Quarles, Marian Lammers LINE PRODUCER Ada Goossens PRODUCER Topkapi Films Frans van Gestel, Laurette Schillings, Arnold Heslenfeld CO-PRODUCER Man Up Film Halina Reijn, Carice van Houten BROADCASTER BNNVARA Gemma Derksen, Robert Kievit FINANCIERS Nederlands Film Fonds, Netherlands Production Incentive, CoBo DISTRIBUTOR September Film Distribution LENGTH 98’ INTERNATIONAL SALES Films Boutique CAST NICOLINE Carice van Houten IDRIS Marwan Kenzari Marie-Mae van Zuilen Pieter Embrechts Betty Schuurman Ariane Schluter Maria Kraakman Tamar van den Dop Robert de Hoog Juda Goslinga SYNOPSIS In spite of her expertise and experience, a seasoned psychologist is completely infatuated by the sex offender she is treating in a penal institution. Nicoline, an experienced psychologist, starts a new job at a penal institution. She meets Idris, a sex offender who committed a series of grave crimes. After five years of treatment, he is about to go on his first unaccompanied probation. -

Alex Van Warmerdam

1987 Alex van Warmerdam, De hand van een SELECTED COLLECTIONS vreemde, Nieuw Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Alex van Warmerdam SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS EYE Filmmuseum, Amsterdam (NL) 1987 2021 GRIMM, Amsterdam (NL) [forthcoming] Museum Voorlinden, Wassenaar (NL) b. 1952 in Haarlem (NL) 1986 Alex van Warmerdam, Abel, De Bezige Bij, 2018 Tronies, GRIMM, Amsterdam (NL) Amsterdam, 1986 Stedelijk Museum, Schiedam (NL) Lives and works in Amsterdam (NL) Alex van Warmerdam - L’histoire kaputt, Eye FILMS Filmmuseum, Amsterdam (NL) EDUCATION 2021 Nr. 10 [forthcoming] 2010 Alex van Warmerdam, schilderijen, film, 2019 Grimm (re-edit) 1974 Printmaking and painting, Gerrit Rietveld theater, Stedelijk Museum Schiedam (NL) Academie, Amsterdam (NL) 2015 Schneider vs. Bax 1969 Letterpress printing, Grafische School, 2013 Borgman Amsterdam (NL) SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2012 Blackout 2020 Diepgeworteld, Bomen in de Nederlandse schilderkunst, Dordrechts Museum, 2009 De laatste dagen van Emma Blank AWARDS Dordrecht (NL) 2006 Ober 2016 Gouden Kalf voor de Filmcultuur (NL) 2018 In-house exhibition, curated by Jorg Grimm, 2003 Grimm 2015 Schneider vs. Bax, Prix Nouveau Genre, Manifesta, Amsterdam (NL) 1998 Kleine Teun Festival D Cinema De Paris (FR) Gerrit turns 50, Willem only 28, Gerrit 2013 Borgman, Golden Tower Award for Best Film Rietveld Academie, Amsterdam (NL) 1996 De jurk (RS) Rhapsody in Blue, Museum Voorlinden, 1992 De Noorderlingen Borgman, Palme d’Or (FR) [nominee] Wassenaar (NL) 1986 Abel / Voyeur Borgman, Gouden Kalf (NL) Pop-up GRIMM, Brussels (BE) 1984 De Stedeling Total oeuvre (film), City of Athens Golden 2017 Het vlot. Kunst is (niet) eenzaam, curated by Athena Award (GR) Jan Fabre, various locations in Oostende (BE) THEATRE 2011 Bij het kanaal naar links, Taalunie 2013 Gedeelde Passie, Stedelijk Museum Toneelschrijfprijs (NL/BE) Schiedam (NL) 2016 Het gelukzalige 2010 Johannes Vermeer Prijs (NL) 2011 Bij het kanaal naar links 2009 De laatste dagen van Emma Blank, Gouden PUBLICATIONS 2007 Wees ons genadig Kalf (NL) 2018 Alex van Warmerdam, l’Histoire Kaputt. -

Humour and Irony in Dutch Post-War Fiction Film FRAMING FILM

HUMOUR AND IRONY IN DUTCH POST-WAR FICTION FILM FRAMING FILM FRAMING FILM is a book series dedicated to theoretical and analytical studies in restoration, collection, archival, and exhibition practices in line with the existing archive of EYE Filmmuseum. With this series, Amsterdam University Press and EYE aim to support the academic research community, as well as practitioners in archive and restoration. SERIES EDITORS Giovanna Fossati, EYE Filmmuseum & University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands Leo van Hee, EYE Filmmuseum Frank Kessler, Utrecht University, the Netherlands Patricia Pisters, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands Dan Streible, New York University, United States Nanna Verhoeff, Utrecht University, the Netherlands EDITORIAL BOARD Richard Abel, University of Michigan, United States Jane Gaines, Columbia University, United States Tom Gunning, University of Chicago, United States Vinzenz Hediger, Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany Martin Koerber, Deutsche Kinemathek, Germany Ann-Sophie Lehmann, University of Groningen, the Netherlands Charles Musser, Yale University, United States Julia Noordegraaf, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands William Uricchio, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, United States Linda Williams, University of California at Berkeley, United States PETER VERSTRATEN HUMOUR AND IRONY IN DUTCH POST-WAR FICTION FILM AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS This publication is made possible by grants from the Nederlands Filmfonds and the Netherlands Society of Cinematographers. Published by EYE Filmmuseum / Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Borgman © Drafthouse Films. Design: Brandon Schaefer. Cover design and lay-out: Magenta Ontwerpers, Bussum Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 943 0 e-isbn 978 90 4852 837 0 doi 10.5117/9789089649430 nur 670 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) P. -

Alex Van Warmerdam 2018 Tronies, GRIMM, Amsterdam (NL) B

SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS Alex van Warmerdam 2018 Tronies, GRIMM, Amsterdam (NL) b. 1952 in Haarlem (NL) Alex van Warmerdam - L’histoire kaputt, Eye Lives and works in Amsterdam (NL) Filmmuseum, Amsterdam (NL) 2010 Alex van Warmerdam, schilderijen, film, EDUCATION theater, Stedelijk Museum Schiedam (NL) 1974 Printmaking and painting, Gerrit Rietveld Academie, Amsterdam (NL) SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 1969 Letterpress printing, Grafische School, Amsterdam (NL) 2018 In-house exhibition, curated by Jorg Grimm, Manifesta, Amsterdam (NL) Gerrit turns 50, Willem only 28, Gerrit AWARDS Rietveld Academie, Amsterdam (NL) 2016 Gouden Kalf voor de Filmcultuur (NL) Rhapsody in Blue, Museum Voorlinden, 2015 Schneider vs. Bax, Prix Nouveau Genre, Wassenaar (NL) Festival D Cinema De Paris (FR) Pop-up GRIMM, Brussels (BE) 2013 Borgman, Golden Tower Award for Best Film 2017 Het vlot. Kunst is (niet) eenzaam, curated by (RS) Jan Fabre, various locations in Oostende (BE) Borgman, Palme d’Or (FR) [nominee] 2013 Gedeelde Passie, Stedelijk Museum Borgman, Gouden Kalf (NL) Schiedam (NL) Total oeuvre (film), City of Athens Golden Athena Award (GR) PUBLICATIONS 2011 Bij het kanaal naar links, Taalunie 2018 Alex van Warmerdam, l’Histoire Kaputt. Eye Toneelschrijfprijs (NL/BE) Filmmuseum & Nieuw Amsterdam, 2010 Johannes Vermeer Prijs (NL) Amsterdam, 2018 2009 De laatste dagen van Emma Blank, Gouden 2016 Alex van Warmerdam, Het gelukzalige, Nieuw Kalf (NL) Amsterdam, Amsterdam, 2016 2008 De laatste dagen van Emma Blank, European 2014 Alex van Warmerdam, Ik heb de wereld Cinema Award geschapen, Nieuw Amsterdam, Amsterdam, 2014 2006 Ober, Gouden Kalf (NL) 2011 Alex van Warmerdam, Bij het kanaal naar 2004 Grimm, Skrien Afficheprijs (NL) links, Nieuw Amsterdam, Amsterdam, 2011 1997 De Jurk, L.J. -

37Th Portland International Film Festival, the Northwest Film Center’S Annual Showcase of New World Cinema

THE NORT HWEST FILM CENTER / PORTLAND ART M USE UM PRESENTS 3 7TH PORTLAND INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL SPONSORED BY: THE OREGONIAN / THE PAUL G. ALLEN FAMILY FOUNDATION F E BRU ARY 6–22, 2014 WELCOME Welcome to the 37th Portland International Film Festival, the Northwest Film Center’s annual showcase of new world cinema. Like the Film Center’s Northwest Filmmakers’ Festival, which surveys outstanding new work by our region’s media makers, the Portland International Film Festival explores not only the art of film but also the world around us, no matter the place or the language spoken. The Festival is not just for cinephiles. The cultural diversity, the extraordinary range of subjects, genres, and experiences explored—for all ages and from matinee to midnight—invite exploration and discovery, movie-lover or not. We welcome you to join in this shared cinematic and community experience and let us know your reaction to the films and the event. We want to know, and the filmmakers want to know. If you are a Festival regular, you will recognize the many longtime sponsors who support the Festival and the Film Center. The array of Festival supporters is both impressive and appreciated. We thank them all for their ongoing support and are truly thankful for your efforts to let them know in the ways you can that this event is a valued part of your, and Portland’s, cultural mix. The gratitude, of course, extends to our Silver Screen Club members, to hundreds of volunteers and industry supporters, and to the dedicated, film-loving Film Center staff whose amazing, resourceful efforts make it all possible. -

Alex Van Warmerdam(Director / Writer)

INTERNATIONAL SALES HEAD OFFICE ASIA OFFICE CANNES OFFICE Van Diemenstraat 100 Unit A, 26/F., CKK Commercial Centre 1st floor (Apt. Zanzi) 1013 CN, Amsterdam 289-295 Hennessy Road, 5 Square Mérimée The Netherlands Wanchai, Hong Kong, S.A.R. Tel: +33 4 93 39 87 31 Tel: +31 20 627 3215 Tel: +852 2311 8081 [email protected] Fax: +31 20 626 1155 Fax: +852 2311 8023 [email protected] [email protected] INTERNATIONAL PRESS LONDON CANNES, FRANCE 192-198 Vauxhall Bridge Road DDA Public Relations Ltd London SW1V 1DX Hotel Majestic, Salon Royan 1 Phone: +44 207 932 9800 1st Floor, 10 La Croisette Fax: +44 207 932 4950 E-mail : [email protected] Tiffany Kizito M:+33 6 66 67 70 60 P: +33 (0) 4 97 06 85 15 E-mail : [email protected] www.ddapr.com www.fortissimofilms.com CREDITS: MAIN CAST: COPYRIGHT NOTICE: written and directed by Alex van Warmerdam Borgman Jan Bijvoet Graniet Film, Epidemic, DDF/Angel Films, NTR director of photography Tom Erisman NSC Marina Hadewych Minis production design Geert Paredis Richard Jeroen Perceval TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS: editor Job ter Burg NCE Stine Sara Hjort Ditlevsen Running Time 113 min music Vincent van Warmerdam Ilonka Eva van de Wijdeven Gauge DCP 2K, 24fps, Color costumes Stine Gudmundsen-Holmgreen Brenda Annet Malherbe Aspect Ratio cinemascope 1:2.35 make up Marike Willard-Hoogveld Pascal Tom Dewispelaere Sound Dolby Stereo 5.1 sound design Peter Warnier Ludwig Alex van Warmerdam Country of Production The Netherlands/Belgium/Denmark casting Annet Malherbe Year 2013 producer Marc van Warmerdam Genre Thriller coproducers Eurydice Gysel, Koen Mortier, Language Dutch Mogens Glad, Tine Mosegaard Originally Shot on Arri Alexa, prores, log C444 line producer Berry van Zwieten Borgman’s arrival in the tree-lined avenues of an exclusive residential area is the beginning of a series of unsettling events around the carefully constructed facade of a wealthy couple, their three children and the nanny. -

The Low Countries. Jaargang 2

The Low Countries. Jaargang 2 bron The Low Countries. Jaargang 2. Stichting Ons Erfdeel, Rekkem 1994-1995 Zie voor verantwoording: https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_low001199401_01/colofon.php Let op: werken die korter dan 140 jaar geleden verschenen zijn, kunnen auteursrechtelijk beschermd zijn. i.s.m. 10 Brussels, City of the Coming Century Hidden bilingualism Foreigners who come to live in Belgium soon realise that they have arrived in a bilingual country. Many of them, those who work for the European institutions and the private companies which cluster around them, live either in the centre of the capital city, Brussels, or else very nearby. I am constantly amazed by the fact that these people see Brussels as an exclusively Frenchspeaking city. Even Dutch people, who speak the same language as Flemings, are able to miss the bilingualism of this city, which is so obvious to me. Worse still, a great many Flemings, themselves Belgians, assume without any further consideration that Brussels is French-speaking, even though Brussels is the capital of their own Flemish Community. Can these people not see? Can they not hear? All the street name plates and road signs are bilingual, with combinations which are sometimes very original, such as ‘Schae/arbeek’ or ‘centre/um’, and sometimes almost surrealistic, such as ‘Treurenberg/Treurenberg’. Every notice in every town hall and post office is bilingual, and the counter staff have to be able to speak both languages. The metro and tram systems are completely bilingual, although some employees still obstinately refuse to understand simple phrases like ‘one tram card please’ or ‘how much does this cost?’ if they are said in Dutch. -

Humour and Irony in Dutch Post-War Fiction Film Framing Film

HUMOUR AND IRONY IN DUTCH POST-WAR FICTION FILM FRAMING FILM FRAMING FILM is a book series dedicated to theoretical and analytical studies in restoration, collection, archival, and exhibition practices in line with the existing archive of EYE Filmmuseum. With this series, Amsterdam University Press and EYE aim to support the academic research community, as well as practitioners in archive and restoration. SERIES EDITORS Giovanna Fossati, EYE Filmmuseum & University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands Leo van Hee, EYE Filmmuseum Frank Kessler, Utrecht University, the Netherlands Patricia Pisters, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands Dan Streible, New York University, United States Nanna Verhoeff, Utrecht University, the Netherlands EDITORIAL BOARD Richard Abel, University of Michigan, United States Jane Gaines, Columbia University, United States Tom Gunning, University of Chicago, United States Vinzenz Hediger, Goethe University Frankfurt, Germany Martin Koerber, Deutsche Kinemathek, Germany Ann-Sophie Lehmann, University of Groningen, the Netherlands Charles Musser, Yale University, United States Julia Noordegraaf, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands William Uricchio, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, United States Linda Williams, University of California at Berkeley, United States PETER VERSTRATEN HUMOUR AND IRONY IN DUTCH POST-WAR FICTION FILM AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS This publication is made possible by grants from the Nederlands Filmfonds and the Netherlands Society of Cinematographers. Published by EYE Filmmuseum / Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Borgman © Drafthouse Films. Design: Brandon Schaefer. Cover design and lay-out: Magenta Ontwerpers, Bussum Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 943 0 e-isbn 978 90 4852 837 0 doi 10.5117/9789089649430 nur 670 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) P. -

Alex Van Warmerdam

SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 1997 De Jurk, Uitgeverij International Theatre & SELECTED COLLECTIONS Film Books, Amsterdam (NL) Alex van Warmerdam 2021 GRIMM, Amsterdam (NL) [forthcoming] EYE Filmmuseum, Amsterdam (NL) 1987 De hand van een vreemde, Nieuw 2018 Tronies, GRIMM, Amsterdam (NL) Museum Voorlinden, Wassenaar (NL) b. 1952 in Haarlem (NL) Amsterdam, Amsterdam (NL) Alex van Warmerdam - L’histoire kaputt, Eye Stedelijk Museum, Schiedam (NL) 1986 Abel, De Bezige Bij, Amsterdam (NL) Lives and works in Amsterdam (NL) Filmmuseum, Amsterdam (NL) 2010 Alex van Warmerdam, schilderijen, film, FILMS EDUCATION theater, Stedelijk Museum Schiedam (NL) 1974 Printmaking and painting, Gerrit Rietveld 2021 Nr. 10 [forthcoming] Academie, Amsterdam (NL) 2019 Grimm (re-edit) SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 1969 Letterpress printing, Grafische School, 2015 Schneider vs. Bax Amsterdam (NL) 2021 Inaugural exhibition, GRIMM, New York, NY (US) 2013 Borgman 2020 Diepgeworteld, Bomen in de Nederlandse 2012 Blackout AWARDS schilderkunst, Dordrechts Museum, 2009 De laatste dagen van Emma Blank 2016 Gouden Kalf voor de Filmcultuur (NL) Dordrecht (NL) 2006 Ober 2015 Schneider vs. Bax, Prix Nouveau Genre, 2018 In-house exhibition, curated by Jorg Grimm, Festival D Cinema De Paris (FR) Manifesta, Amsterdam (NL) 2003 Grimm 2013 Borgman, Golden Tower Award for Best Film Gerrit turns 50, Willem only 28, Gerrit 1998 Kleine Teun (RS) Rietveld Academie, Amsterdam (NL) 1996 De jurk Borgman, Palme d’Or (FR) [nominee] Rhapsody in Blue, Museum Voorlinden, 1992 De Noorderlingen Wassenaar