Alan Rabinowitz Biography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Status of Selected Mammal Species in North Myanmar

ORYX VOL 32 NO 3 JULY 1998 Status of selected mammal species in North Myanmar Alan Rabinowitz and Saw Tun Khaing During 1996 and 1997, data on the status of selected mammal species were collected from a remote region of North Myanmar. Of the 21 species discussed in this paper, the black muntjac, stone marten and blue sheep are new records for the country. One species, the leaf muntjac, has never been described. At least three species that once inhabited the region - elephant, gaur and Sumatran rhinoceros - are no longer present, and the tiger has been nearly extirpated. Himalayan species that are declining elsewhere, such as takin, red goral and red panda, are still relatively abundant despite hunting pressures. Musk deer are in serious decline. The wolf, while not positively confirmed, may be an occasional inhabitant of North Myanmar. Introduction declared the area north of the Nam Tamai River to the Chinese border as Hkakabo-Razi The area called North Myanmar, between Protected Area (Figure 1), but no government 24-28°N and 97-99°E, is a narrow strip along staff had recently visited the region. During the western escarpment of Yunnan Province in March 1996 the authors travelled to the town China, once part of a continuous land forma- of Putao and surrounding villages west of the tion comprising the Tibetan Plateau to the Mali Hka River (Figure 1). The following year, north and the China Plateau to the east between 23 February and 29 April 1997, a bio- (Kingdon-Ward, 1944). This mountainous re- logical expedition was organized with the gion contains floral communities of Miocene Forest Department into the Hkakabo-Razi origin, which have been isolated since the last Protected Area, and travelled as far north as glaciation (Kingdon-Ward, 1936, 1944). -

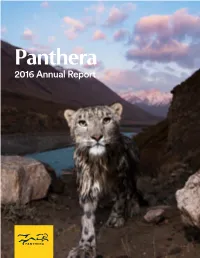

2016 Annual Report

Panthera 2016 Annual Report 2016 ANNUAL REPORT — 1 “I COULD HARDLY BELIEVE MY EYES” Our cover image captures the moment after a snow leopard crossed the freezing Uchkul River in Sarychat- Ertash State Nature Reserve in eastern Kyrgyzstan. The photographer, Sebastian Kennerknecht, had hiked for miles in the thin mountain air looking for spots to place camera traps—and when he retrieved this image, he could hardly believe his eyes. “A gorgeous snow leopard, dripping wet in front of a sunrise-lit alpine sky, was staring straight at me,” he said. “I was so grateful that this cat allowed us a glimpse into its otherwise secretive life. “As a wildlife photographer,” he continued, “this image is incredibly special to me, but as a conservationist, it’s important to appreciate why it can exist in the first place. Panthera’s actions in Kyrgyzstan … are major reasons snow leopards still inhabit this part of central Asia. Their work is critical, and I am proud to be able to support it through my photography.” 2 — 2016 ANNUAL REPORT Panthera 2016 Annual Report 2016 ANNUAL REPORT — 1 2 — 2016 ANNUAL REPORT A cheetah cub in the Arusha Region of Tanzania Contents 03 04 06 08 Panthera's A Message from A Decade of A Message from Mission the Chairman Saving Big Cats the CEO 09 32 34 36 Program The Science of Artistic Allies in Changing the Highlights Saving Cats Cat Conservation Game 37 38 42 45 2016 Financial Board, Staff, and 2016 Scientific Investing Summary Council Listings Publications in Landscapes 2016 ANNUAL REPORT — 3 4 — 2016 ANNUAL REPORT A young jaguar in Emas National Park in the Brazilian Cerrado Panthera's Mission Panthera’s mission is to ensure a future for wild cats and the vast landscapes on which they depend. -

An Indomitable Beast: the Remarkable Journey of the Jaguar Pdf

FREE AN INDOMITABLE BEAST: THE REMARKABLE JOURNEY OF THE JAGUAR PDF Alan Rabinowitz | 304 pages | 07 Nov 2014 | Island Press | 9781597269964 | English | Washington, United States An Indomitable Beast: The Remarkable Journey of the Jaguar - Alan Rabinowitz - Google книги EcoLit Books. Expect to learn a bit about the history of species conservation as Alan Rabinowitz, CEO of Pantheraa nonprofit dedicated to big cat conservation, tells the story of his work to protect the jaguar in An Indomitable BeastIsland Press. Along the way, the book presents numerous ideas of interest to anyone interested in jaguar, specifically, or species conservation, in general. Despite this sobering realization as a young child, I also realized that if the cats and other animals at the zoo had a human voice, if they could cry, laugh or plead their case, An Indomitable Beast: The Remarkable Journey of the Jaguar would not be locked up so easily in small cages for display. They would never have that human voice—but I would, I was sure of An Indomitable Beast: The Remarkable Journey of the Jaguar. And when I found that voice, I promised the cats at the zoo, every time I visited them, that I would be their voice. I would find a place for us. Rabinowitz displays an impressive dedication to and love for this animal, which he demonstrates through scientific research, action, and advocacy. What to read next? The Snow Leopard by Peter Matthiessen. Read the EcoLit review. Inspired by this book? Visit Panthera. Facebook Twitter Share by email. Bio Latest Posts. Shel Graves. Latest posts by Shel Graves see all. -

'Genetic Corridors' Are Next Step to Saving Tigers 13 February 2008

'Genetic corridors' are next step to saving tigers 13 February 2008 other tiger conservationists would be seeking additional approval and assistance from other heads of state. “While Asia’s economic tigers are on the rise, wild tigers in Asia are in decline,” Rabinowitz said. “Much like the call-out for global agreements on banning tiger parts in trade, a similar cross-border initiative for genetic corridors is key to the survival of the tiger. Tiger range states need to work together, as tigers do not observe political borders nor do they require a visa or passport to travel where habitat and prey remain.” A tiger caught in a camera trap in Myanmar. Credit: Wildlife Conservation Society Rabinowitz said corridors did not have to be pristine parkland but could in fact include agricultural areas, ranches, and other multi-use landscapes – just as long as tigers could use them to travel between The Wildlife Conservation Society and the wilderness areas. Panthera Foundation announced plans to establish a 5,000 mile-long “genetic corridor” from Bhutan “We’re not asking countries to set aside new parks to Burma that would allow tiger populations to to make this corridor a success,” Rabinowitz said. roam freely across landscapes. The corridor, first “This is more about changing regional zoning in announced at the United Nations on January 30th, tiger range states to allow tigers to move more would span eight countries and represent the freely between areas of good habitat.” largest block of tiger habitat left on earth. Twelve of 13 tiger range states were represented Dr. -

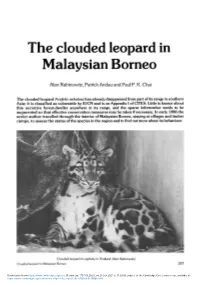

The Clouded Leopard in Malaysian Borneo

The clouded leopard in Malaysian Borneo Alan Rabinowitz, Patrick Andau and Paul P. K. Chai The clouded leopard Neofelis nebulosa has already disappeared from part of its range in southern Asia; it is classified as vulnerable by IUCN and is on Appendix I of CITES. Little is known about this secretive forest-dweller anywhere in its range, and the sparse information needs to be augmented so that effective conservation measures may be taken if necessary. In early 1986 the senior author travelled through the interior of Malaysian Borneo, staying at villages and timber camps, to assess the status of the species in the region and to find out more about its behaviour. Clouded leopard in captivity in Thailand (Alan Rabinowitz). Clouded leopard in Malaysian Borneo 107 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.8, on 26 Sep 2021 at 11:28:03, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605300026648 The clouded leopard is one of the most elusive of the larger felids in Asian forests. With body characteristics that fall between those of large and small cats, it has upper canines that are relatively longer than in any other living felid (Guggisberg, 1975). These tusk-like canines have a sharp posterior edge, which caused Sterndale (1884) to compare the clouded leopard to the extinct sabre-toothed tiger. Occurring over an extensive area of southern Asia, the clouded leopard is the largest wild felid on the island of Borneo. Due to its secretive and solitary habits, however, this cat is seldom observed, and much of the knowledge con- cerning its ecology remains anecdotal. -

Alan Rabinowitz

A Nonprofit Organization FALL 2018 Since 1947... Helping Those Who Stutter REMEMBERING ALAN RABINOWITZ CELEBRATING HIS LIFE AND LEGACY 1953-2018 “For the past 25 years of my life, I have lived in and “Alan’s courage is particularly inspiring explored some of the most remote places on earth. I have to young people whose career paths lived for days in caves chasing bats, I have captured and have yet to be decided and for whom tracked bears, jaguars, leopards, tigers, and rhinos. I stuttering often seems an insurmountable have discovered new animal species in northern Burma obstacle,” said Stuttering Foundation and in the cloud forests of the Annamite Mountains. I president, Jane Fraser. “Through hard have documented lost cultures such as the Taron, the work, perseverance and dedication world’s only Mongoloid pygmies. I have been called the to his true passions, Alan never let stuttering hold him back from his quest ‘Indiana Jones of Wildlife’ by Time magazine and given to help endangered animals.” Alan told lectures all over the world to thousands of people. Yet his inspiring story in a 2011 Stuttering not a year has passed, not a country traveled in, when Foundation DVD entitled Stuttering and I have not felt again the little stuttering, insecure boy the Big Cats, which has been widely inside who’d come home from school and hide in a corner used in public school speech therapy of his closet. That boy is never far from the surface.” programs. In addition, Dr. Rabinowitz was the author of seven books on wildlife conservation, including the 2014 children's book A Boy and a Jaguar, Both the worldwide stuttering and animal which delightfully illustrates the story of conservation communities have lost a tireless his childhood promise at the Bronx Zoo. -

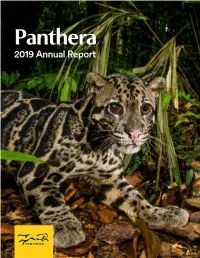

2019 Annual Report Panthera’S Mission Is to Ensure a Future for Wild Cats and the Vast Landscapes on Which They Depend

Panthera 2019 Annual Report Panthera’s mission is to ensure a future for wild cats and the vast landscapes on which they depend. Panthera Our vision is a world where wild cats thrive in healthy, natural and developed landscapes that sustain people and biodiversity. Contents 04 08 12 14 Nature Bats Last Cores and Conservation Program by Thomas S. Kaplan, Ph.D. Corridors in a Global Highlights Community 34 36 38 40 CLOUDIE ON CAMERA The Arabian A Corridor Searching for Conservation “I am particularly fond of this photograph of a clouded leopard Leopard to the World New Frontiers Science and because of the high likelihood that I wouldn’t capture it. After a leech and mosquito-filled five-day jungle trek, the biologists Initiatives Technology and I arrived at a ranger station at the top of the mountain in Highlights Malaysian Borneo, close to where this camera trap was located. I checked it but saw the battery was on its last leg. I decided to take the grueling full day’s hike back and forth to pick up a fresh battery. When I checked it the following afternoon, this young adult had come through just hours before. The physical 43 44 46 49 exhaustion was totally worth getting this amazing photograph.” 2019 Financial Board, Staff and Conservation After the Fires - Sebastian Kennerknecht, Panthera Partner Photographer Summary Science Council Council by Esteban Payán, Ph.D. 2 — 2019 ANNUAL REPORT A leopard in the Okavango Delta, Botswana Nature Bats Last The power of nature is an awesome thing to contemplate. the Jaguar Corridor. -

Status of Selected Mammal Species in North Myanmar

ORYX VOL 32 NO 3 JULY 1998 Status of selected mammal species in North Myanmar Alan Rabinowitz and Saw Tun Khaing During 1996 and 1997, data on the status of selected mammal species were collected from a remote region of North Myanmar. Of the 21 species discussed in this paper, the black muntjac, stone marten and blue sheep are new records for the country. One species, the leaf muntjac, has never been described. At least three species that once inhabited the region – elephant, gaur and Sumatran rhinoceros – are no longer present, and the tiger has been nearly extirpated. Himalayan species that are declining elsewhere, such as takin, red goral and red panda, are still relatively abundant despite hunting pressures. Musk deer are in serious decline. The wolf, while not positively confirmed, may be an occasional inhabitant of North Myanmar. Introduction declared the area north of the Nam Tamai River to the Chinese border as Hkakabo-Razi The area called North Myanmar, between Protected Area (Figure 1), but no government 24–28˚N and 97–99˚E, is a narrow strip along staff had recently visited the region. During the western escarpment of Yunnan Province in March 1996 the authors travelled to the town China, once part of a continuous land forma- of Putao and surrounding villages west of the tion comprising the Tibetan Plateau to the Mali Hka River (Figure 1). The following year, north and the China Plateau to the east between 23 February and 29 April 1997, a bio- (Kingdon-Ward, 1944). This mountainous re- logical expedition was organized with the gion contains floral communities of Miocene Forest Department into the Hkakabo-Razi origin, which have been isolated since the last Protected Area, and travelled as far north as glaciation (Kingdon-Ward, 1936, 1944). -

MM •R.N- Mis MM--Q3O

MM •R.N- mis _ MM--Q3O MM0200043 1. Introduction: The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) is one the world's leading NGOs involved in conserving wildlife and ecosystems throughout the world through research, training and education. It was founded in April, 1895 with the initial aim of establishing a zoo at New York City, United States for educating the public about wildlife. At that time it was called "The New York Zoological Society." Through the concerted efforts of the Society, the "Bronx Zoo" was established where the Society has its offices now. The Society is actively involved not only in zoological work but also in world-wide conservation activities and accordingly changed the name of the Society to "The Wildlife Conservation Society" in 1993 to indicate its interest in wildlife conservation work all over the globe. Currently WCS is running over 300 wildlife conservation projects with the help of 60 scientists and 100 researchers throughout the world. The WCS Myanmar Program was initiated and founded by Dr. Alan Rabinowitz, Director of Science for Asia who signed the first Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the Forest Department on 29 December 1993 for a period of four years from 1994 to 1997. Due to the successes achieved during this period, a second MoU was signed on 26 September for another five years from 1998 to 2002. At the present time WCS Myanmar Program is cooperating with the Nature and Wildlife Conservation Division of the Forest Department in carrying out wildlife conservation activities throughout the country in line with the framework set out in the MoU. -

The Clouded Leopard in Taiwan Alan Rabinowitz

The clouded leopard in Taiwan Alan Rabinowitz There has never been a thorough survey of Taiwan's clouded leopard population, and some believe it may no longer survive there. The author conducted a preliminary survey in 1986 and discovered that the last reported sighting of the species was in 1983. Swinhoe (1862) described Taiwan's clouded I interviewed 70 people: of 33 reported sightings leopard as a distinct species, Leopardus brac- of the clouded leopard, seven occurred within hyurus, but it is now recognized as a subspecies, the last five years, three were between five and Neofelis nebulosa brachyurus. There has never ten years ago, and 23 occurred more than ten been a definitive survey of the status of the years ago. Many of the people interviewed, who clouded leopard in Taiwan; its past and present had never seen clouded leopards, knew of this population numbers are a mystery. This cat was cat being seen or killed by old hunters who had already believed to be reduced to dangerously since died. These sightings dated from at least low levels over 15 years ago (Wayre, 1969). 20 years ago, often from the Japanese occu- pation (1895-1945), when Japanese soldiers McCullough (1974) reported the clouded paid high prices for clouded leopard skins. leopard as possibly still existing in remote regions of the Central Mountain Range of The seven recent sightings were between 1981 Taiwan. However, direct evidence of this cat and 1983; five occurred within the present has been so sparse in recent years that some boundaries of Yu-Shan National Park, and two Taiwanese believe it to be extinct. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

THE ECOLOGY AND CONSERVATION OF JAGUARS (Panthera onca) IN CENTRAL BELIZE: CONSERVATION STATUS, DIET, MOVEMENT PATTERNS AND HABITAT USE By OMAR ANTONIO FIGUEROA A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Omar Antonio Figueroa 2 To Desi, Rhiannon, Mary Elizabeth, Kylie and Justin To Superman 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A study such as this could never be a singular effort. I am extremely grateful and indebted to so many individuals and numerous organizations. At the risk of failing to mention or acknowledge individuals who have somehow helped along the way I hereby venture to express my sincere gratitude to the many folks who have provided assistance and guidance along this long and many times difficult endeavor. At the university level, I would not have been able to reach this milestone were it not for the help and guidance of Susan Jacobson, my major professor. Simply put, without her help and support I would not have been able to finish this degree program. I am extremely grateful for her help, guidance and for the critical review on my dissertation. I am also immensely grateful for the other member of my committee, Ken Meyer, Eric Keys, Leonard Pearlstine, Peter Frederick and Howard Quigley for all the help and guidance provided during the development of the research proposal up until the final dissertation was completed. Thanks so much for assisting on the academic front. I thank Wilber Martinez, Reynold Cal, David Tzul and Gilford Hoare for their valuable field assistance in what was sometimes extremely difficult field conditions. -

Obituary NAT

Obituary NAT. HIST. BULL. SIAM SOC. 64 (1): 11–15, 2020 Alan Rabinowitz, 1953 –2018 Dr. Alan Rabinowitz, world-renowned champion of wild cat conservation, died of lymphocytic leukemia in New York on August 5, 2018. He helped to advance conservation in Thailand and neighboring countries, and contributed as an author and editor to the Natural History Bulletin of the Siam Society. His colorful career took off in 1982 when he was recruited by the New York Zoological Society (NYZS) to study jaguars in Belize. He carried out the first scientific study of the ecology of the species there, which earned him a staff position at the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), the conservation arm of NYZS where he worked for nearly all of his career. Rabinowitz was dismayed by the poaching and habitat destruction he witnessed in Belize, and began a crusade to save the jaguar, the top predator of the American tropical forest ecosystem. In 1986, he persuaded the government of Belize to create the Cockscomb Basin Jaguar Preserve, turning the tide on the loss of the country’s wild heritage. He would, in later years near the end of his life, extend the conservation of jaguars down a corridor through Latin America from Mexico to Argentina. Rabinowitz’s contributions to conservation are best appreciated by reading his four major books on his campaigns to promote research and conservation of cats and other wild species. His first book, Jaguar: One Man’s Struggle to Establish the World’s First Jaguar Preserve (New York: Arbor House, 1986), established the genre.