Radicalism in the Mountian West, 1890-1920: Socialists, Populists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEWER SYNDICALISM: WORKER SELF- MANAGEMENT in PUBLIC SERVICES Eric M

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NVJ\14-2\NVJ208.txt unknown Seq: 1 30-APR-14 10:47 SEWER SYNDICALISM: WORKER SELF- MANAGEMENT IN PUBLIC SERVICES Eric M. Fink* Staat ist ein Verh¨altnis, ist eine Beziehung zwischen den Menschen, ist eine Art, wie die Menschen sich zu einander verhalten; und man zerst¨ort ihn, indem man andere Beziehungen eingeht, indem man sich anders zu einander verh¨alt.1 I. INTRODUCTION In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, municipal govern- ments in various US cities assumed responsibility for utilities and other ser- vices that previously had been privately operated. In the late twentieth century, prompted by fiscal crisis and encouraged by neo-liberal ideology, governments embraced the concept of “privatization,” shifting management and control over public services2 to private entities. Despite disagreements over the merits of privatization, both proponents and opponents accept the premise of a fundamental distinction between the “public” and “private” sectors, and between “state” and “market” institutions. A more skeptical view questions the analytical soundness and practical signifi- cance of these dichotomies. In this view, “privatization” is best understood as a rhetorical strategy, part of a broader neo-liberal ideology that relies on putative antinomies of “public” v. “private” and “state” v. “market” to obscure and rein- force social and economic power relations. While “privatization” may be an ideological definition of the situation, for public service workers the difference between employment in the “public” and “private” sectors can be real in its consequences3 for job security, compensa- * Associate Professor of Law, Elon University School of Law, Greensboro, North Carolina. -

Libertarian Municipalism: an Overview

Murray Bookchin Libertarian Municipalism: An Overview 1991 The Anarchist Library Contents A Civic Ethics............................. 3 Means and Ends ........................... 4 Confederalism............................. 5 Municipalizing the Economy .................... 7 Addendum ............................... 9 2 Perhaps the greatest single failing of movements for social recon- struction — I refer particularly to the Left, to radical ecology groups, and to organizations that profess to speak for the oppressed — is their lack of a politics that will carry people beyond the limits es- tablished by the status quo. Politics today means duels between top-down bureaucratic parties for elec- toral office, that offer vacuous programs for “social justice” to attract a nonde- script “electorate.” Once in office, their programs usually turn into a bouquet of “compromises.” In this respect, many Green parties in Europe have been only marginally different from conventional parliamentary parties. Nor have so- cialist parties, with all their various labels, exhibited any basic differences from their capitalist counter parts. To be sure, the indifference of the Euro-American public — its “apoliticism” — is understandably depressing. Given their low expectations, when people do vote, they normally turn to established parties if only because, as centers of power, they cart produce results of sorts in practical matters. If one bothers to vote, most people reason, why waste a vote on a new marginal organization that has all the characteristics of the major ones and that will eventually become corrupted if it succeeds? Witness the German Greens, whose internal and public life increasingly approximates that of other parties in the new Reich. That this “political process” has lingered on with almost no basic alteration for decades now is due in great part to the inertia of the process itself. -

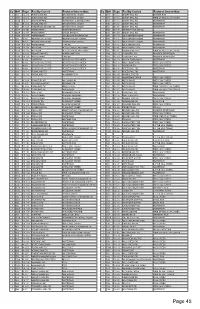

Bridge Index

Co Br# Page Facility Carried Featured Intersedtion Co Br# Page Facility Carried Featured Intersedtion 1 001 12 2-G RISING SUN RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 087 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD BURRIS RUN 1 001A 12 2-G RISING SUN RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 088 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD TRIB OF RED CLAY CREEK 1 001B 12 2-F KENNETT PIKE WATERWAY & ABANDON RR 1 089 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD. WATERWAY 1 002 9 12-G ROCKLAND RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 090 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD. WATERWAY 1 003 9 11-G THOMPSON BRIDGE RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 091 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD. WATERWAY 1 004P 13 3-B PEDESTRIAN NORTHEAST BLVD 1 092 9 11-E KENNET PIKE (DE 52) 1 006P 12 4-G PEDESTRIAN UNION STREET 1 093 9 10-D SNUFF MILL RD WATERWAY 1 007P 11 8-H PEDESTRIAN OGLETOWN STANTON RD 1 096 9 11-D OLD KENNETT ROAD WATERWAY 1 008 9 9-G BEAVER VALLEY RD. BEAVER VALLEY CREEK 1 097 9 11-C OLD KENNETT ROAD WATERWAY 1 009 9 9-G SMITHS BRIDGE RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 098 9 11-C OLD KENNETT ROAD WATERWAY 1 010P 10 12-F PEDESTRIAN I 495 NB 1 099 9 11-C OLD KENNETT RD WATERWAY 1 011N 12 1-H SR 141NB RD 232, ROCKLAND ROAD 1 100 9 10-C OLD KENNETT RD. WATERWAY 1 011S 12 1-H SR 141SB RD 232, ROCKLAND ROAD 1 105 9 12-C GRAVES MILL RD TRIB OF RED CLAY CREEK 1 012 9 10-H WOODLAWN RD. -

Pailu Ialbarker I \ ! I J I J Publishers Co., Inc

Page Six DAILY WORKER, NEW YORK, FRIDAY. FEBRUARY 1, 1929 II I Copyright, 1929, by International, Pailu ialbarker I \ ! I J I J Publishers Co., Inc. Central Organ of the Workers (Communist) Party The desperate financial condition of the Daily Worker has compelled the omission of some of its most attractive features. Published by the National Daily SUBSCRIPTION RATES: Publishing Association, HAYWOOD’S Worker Bv Mail (in New York only): Inc., Daily, Except Sunday, at )s.OO a year $4.50 six months We hope to be able to resume pubMcation of Fred Ellis’ cartoons in the 28-28 Union Square, New York. $2.50 three months All rights rese,~ved. Republica- I I M £ | //' T6 I J § ” York): except by permission. I II Ib9- -8. cable, uaiwukk. Outside of New tion forbidden < Cable\IWOKK* 56.00 a year $3.50 six months next issue. ROBERTrhrvpt MINORxrmrvß EditorTMitnr Address and mail all checks to The of the paper depends upon how much help will be given by rhe DaiJy Workers 2 6-28 Union life the W\l. F. DUNNE Ass. Editor Square, New York, N. Y. workers and friends who are our readers. Gompers Betrayal of the Railway Strikers of What Is “White Civilization” In Africa? Send your contributions QUICK to 1894; Haywood Now a Convinced Already the forces that will drive'European imperialism The DAILYWORKER, Revolutionary Unionist out of the continent of Africa begin to show formidable 26-28 Union Square, strength. The point of greatest friction at present appears to New York. Previous chapters have told of Bill Haywood’s boyhood among the Utah; youth as miner and cowboy in Nevada; mining be in the field ruled over by Great Britain. -

Hard-Rock Mining, Labor Unions, and Irish Nationalism in the Mountain West and Idaho, 1850-1900

UNPOLISHED EMERALDS IN THE GEM STATE: HARD-ROCK MINING, LABOR UNIONS AND IRISH NATIONALISM IN THE MOUNTAIN WEST AND IDAHO, 1850-1900 by Victor D. Higgins A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Boise State University August 2017 © 2017 Victor D. Higgins ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Victor D. Higgins Thesis Title: Unpolished Emeralds in the Gem State: Hard-rock Mining, Labor Unions, and Irish Nationalism in the Mountain West and Idaho, 1850-1900 Date of Final Oral Examination: 16 June 2017 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Victor D. Higgins, and they evaluated his presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. John Bieter, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Jill K. Gill, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Raymond J. Krohn, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by John Bieter, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved by the Graduate College. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author appreciates all the assistance rendered by Boise State University faculty and staff, and the university’s Basque Studies Program. Also, the Idaho Military Museum, the Idaho State Archives, the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, and the Wallace District Mining Museum, all of whom helped immensely with research. And of course, Hunnybunny for all her support and patience. iv ABSTRACT Irish immigration to the United States, extant since the 1600s, exponentially increased during the Irish Great Famine of 1845-52. -

Mining Wars: Corporate Expansion and Labor Violence in the Western Desert, 1876-1920

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 2009 Mining wars: Corporate expansion and labor violence in the Western desert, 1876-1920 Kenneth Dale Underwood University of Nevada Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Latin American History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Underwood, Kenneth Dale, "Mining wars: Corporate expansion and labor violence in the Western desert, 1876-1920" (2009). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 106. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/1377091 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MINING WARS: CORPORATE EXPANSION AND LABOR VIOLENCE IN THE WESTERN DESERT, 1876-1920 by Kenneth Dale Underwood Bachelor of Arts University of Southern California 1992 Master -

The Grande Hub)

THE L M F J GRANDE HUB THE GRANARY DISTRICT SALT LAKE CITY, UT 2.162 ACRES 212 LIHTC UNITS 21,250 ft.2 COMMERCIAL 157,200 ft.2 LIHTC RESIDENTIAL 16.18% COMMERCIAL IRR $50,305,104 $12,933,126 $17,987,921 TOTAL COST TOTAL EQUITY FROM TAX CREDIT SALE VALUE TO TAX CREDIT INVESTOR [credits + tax losses] SITE EVALUATION Once stagnant and in a state of urban decay, the Granary District is currently transforming into a flourishing area of Salt Lake City. Though its character was once defined by blue collar grit, the District is now mixed with creative ambitions and entrepreneurial energy. As its redevelopment potential is exposed, the District is rapidly changing from static surfaces of pavement and underutilized buildings to a dynamic space full of investment opportunities. PROJECT PROPOSAL Based on market research, LMFJ proposes developing affordable housing under the LIHTC model [4% credits] ; a moderate sized, local pharmacy/grocery; and small-scale restaurant. With the current rapid growth and planned restoration projects, maintaining and preserving housing affordability throughout the Granary District must be imperative along with the provision of essential needs. The Granary District, Personal Photographs The basis of our development plan builds upon the vision of the Granary District — a thriving social hub of blue collar workers, entrepreneurs, and creatives who can live comfortably and actively contribute to its revitalization. LEGAL PROFILE The site contains two separate parcels located along 900S and Rio Grande St. To feasibly develop the site, LMFJ proposes purchasing the entire block these parcels are within, and demolishing all existing structures. -

Addendum 1, 12/30/2020 6

CITY OF RIO RANCHO DEPARTMENT OF FINANCIAL SERVICES PURCHASING DIVISION 3200 CIVIC CENTER CIRCLE NE 3rd FLOOR RIO RANCHO, NEW MEXICO 87144 TELEPHONE: 505-896-8769 FAX: 505-891-5762 ADDENDUM NUMBER (1) ONE IFB-21-PW-017 VERANDA ROAD SAFETY IMPROVEMENTS December 30, 2020 Addendum Number (1) One forms part of the contract documents and modifies them in the manner set forth below. ATTENTION CONTRACTORS Questions and Answers Attachments: o Revised Bid Form o Revised Plans o NMDOT Specs: Section 906- Minimum Testing Requirements Questions and Answers: 1. Question: Should there be either a bid item for testing or an allowance for it on this project? Answer: A material testing allowance has been added to the bid tab. See revised bid form attached hereto. 2. Question: Notes on the plans indicate that the header curb associated with the handicap ramps is incidental to the handicap ramps but bid item # 20 calls for 230’ of header curb (which is about the quantity associated with the handicap ramps). Please clarify Answer: Header curb is incidental to the ramps; therefore, quantity has been removed from the plans and Bid Form. 3. Question: Do the valve boxes being adjusted in bid item # 1 require new lids? Answer: If new lids are needed for the adjustments of the valve boxes, they will be considered incidental to the adjustment. 4. Question: Can you provide a Bid Item for Quality Control Testing? Answer: A material testing allowance has been added to the bid tab. See revised bid form attached hereto. 5. Question: What is the existing Pavement thickness for the Removal of Surfacing Bid Item? Answer: The existing pavement thickness is approximately 4 to 6 inches. -

The Masses Index 1911-1917

The Masses Index 1911-1917 1 Radical Magazines ofthe Twentieth Century Series THE MASSES INDEX 1911-1917 1911-1917 By Theodore F. Watts \ Forthcoming volumes in the "Radical Magazines ofthe Twentieth Century Series:" The Liberator (1918-1924) The New Masses (Monthly, 1926-1933) The New Masses (Weekly, 1934-1948) Foreword The handful ofyears leading up to America's entry into World War I was Socialism's glorious moment in America, its high-water mark ofenergy and promise. This pregnant moment in time was the result ofdecades of ferment, indeed more than 100 years of growing agitation to curb the excesses of American capitalism, beginning with Jefferson's warnings about the deleterious effects ofurbanized culture, and proceeding through the painful dislocation ofthe emerging industrial economy, the ex- cesses ofspeculation during the Civil War, the rise ofthe robber barons, the suppression oflabor unions, the exploitation of immigrant labor, through to the exposes ofthe muckrakers. By the decade ofthe ' teens, the evils ofcapitalism were widely acknowledged, even by champions ofthe system. Socialism became capitalism's logical alternative and the rallying point for the disenchanted. It was, of course, merely a vision, largely untested. But that is exactly why the socialist movement was so formidable. The artists and writers of the Masses didn't need to defend socialism when Rockefeller's henchmen were gunning down mine workers and their families in Ludlow, Colorado. Eventually, the American socialist movement would shatter on the rocks ofthe Russian revolution, when it was finally confronted with the reality ofa socialist state, but that story comes later, after the Masses was run from the stage. -

E-LITE 900S Wireless Ethernet Radio

E-LITE 900S Wireless Ethernet Radio HIGH-PERFORMANCE. RUGGEDNESS. RELIABILITY. The E-Lite 900S industrial wireless ethernet radio fills the gap in marketplace created by the lack of high speed 900 Mhz units avaliable. This new addition to the E-Lite family of products takes advantage of the robust and license free 900 MHz band and is engineered with throughput speeds of up to 36 Mbps. When paired with our TS1 serial gateway, the E-Lite 900s can provide control of serial devices such as Variable Message Signs (VMS). Backed by unmatched customer service and warranty, our radios offer features such as: • Adaptive radio modulation • Advanced QoS + Traffic Prioritization • Channel size of 5 to 20 MHz • 3 Gigabit Ethernet ports (1 w/ PoE support) • Enhanced security protocols • Up to 36 Mbps throughput • Noise-resilient COFDM technology • Proprietary eMax protocol KEY BENEFITS Better RF signal propagation Highly resilient signal frequency Configurable channel widths Scalable technology platform Reliable connectivity Unparalleled software management tools Works seamlessly with STRATOS Encom’s E-LITE solutions provide the flexibility to quickly and easily deploy a fast and efficient wireless ecosystem. Features such as adaptive radio modulation, software- defined channel size of 5 to 20 MHz, traffic prioritization, and COFDM technology make the E-LITE 900s highly resilient to RF interference. The E-Lite 900S offers the “best-in-class” data transmission rates while employing robust security protocols such as WPA, WPA2, TKIP, AES, MAC and RADIUS authentication to bring enhanced security to your network. Visualize, Control and Monitor your Encom Wireless Network with STRATOS (works with Stratos I/O or Stratos Elite) www.encomwireless.com E-LITE 900S PHYSICAL SPECIFICATIONS IEEE STANDARDS Dimensions 8.6” x 8.6” x 3.17” 802.11e WMM and QOS Weight 1 Ib. -

Proposed Policy Changes 2020-2021

POLICY UPDATE SUMMARY JUNE 2020 POLICY UPDATE SUMMARY JUNE 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. “750 Bright Line” Overview………………………………………………………………….……………...….…2 2. Residential Flat Rate Premium – Increase……………………………………………...……………..….……3 3. Residential Flat Rate Coverage Maximum – Increase………………………………………...……..….……6 4. Forms 900/901 Eligibility: Maximum Coverage Amount – Decrease…………..……………….….….….…7 5. Participant E & O Minimum “Per Occurrence” Requirement – Increase…………………………….………8 6. Annual Participation Fee – Flat Fee Structure……………………………………………..…….…..………...9 7. E-Payment Requirement……………………………………………….…………………..……………...……10 8. Application E-Submission Requirement………….……………………………………………..…………….11 9. Composite Mortgage Affidavit - Update…………………………………………….…………….….………..12 10. Notice of Availability - Update…………………………………………….…………………………………….13 11. Post-Closing Search Requirement – Update…………………………………………….………………...…14 12. Minimum Abstract Standards - Update…………………………………………….………………………….16 13. Form 900/901 Standards and Manual - Update………………………..…….……………………..………..19 1 | Page 1. “750 Bright Line” Overview Participants and lenders currently experience confusion regarding ITG policies, as the associated thresholds for each policy vary significantly, regularly creating inadvertent results. In a continued effort to improve the title production process, ITG has aligned existing policies to: (i) simplify use of the program for all stakeholders; (ii) clarify ambiguities that currently cause delay and frustration; and (iii) improve compliance oversight efficiency -

Freedom of Speech at the Feast of St. Patrick

Boston University School of Law Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law Faculty Scholarship 11-1993 Parading Ourselves: Freedom of Speech at the Feast of St. Patrick Larry Yackle Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, Judges Commons, Law and Gender Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Sexuality and the Law Commons Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Tue Nov 12 10:47:10 2019 Citations: Bluebook 20th ed. Larry W. Yackle, Parading Ourselves: Freedom of Speech at the Feast of St. Patrick, 73 B.U. L. Rev. 791 (1993). ALWD 6th ed. Larry W. Yackle, Parading Ourselves: Freedom of Speech at the Feast of St. Patrick, 73 B.U. L. Rev. 791 (1993). APA 6th ed. Yackle, L. W. (1993). Parading ourselves: Freedom of speech at the feast of st. patrick. Boston University Law Review, 73(5), 791-872. Chicago 7th ed. Larry W. Yackle, "Parading Ourselves: Freedom of Speech at the Feast of St. Patrick," Boston University Law Review 73, no. 5 (November 1993): 791-872 McGill Guide 9th ed. Larry W Yackle, "Parading Ourselves: Freedom of Speech at the Feast of St. Patrick" (1993) 73:5 BUL Rev 791. MLA 8th ed. Yackle, Larry W. "Parading Ourselves: Freedom of Speech at the Feast of St. Patrick." Boston University Law Review, vol. 73, no. 5, November 1993, p. 791-872. HeinOnline. OSCOLA 4th ed. Larry W Yackle, 'Parading Ourselves: Freedom of Speech at the Feast of St. Patrick' (1993) 73 BU L Rev 791 Provided by: Fineman & Pappas Law Libraries -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at https://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text.