Turing, Kasparov and the Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Development

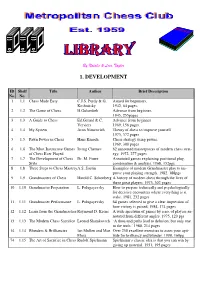

By Natalie & Leon Taylor 1. DEVELOPMENT ID Shelf Title Author Brief Description No. No. 1 1.1 Chess Made Easy C.J.S. Purdy & G. Aimed for beginners, Koshnitsky 1942, 64 pages. 2 1.2 The Game of Chess H.Golombek Advance from beginner, 1945, 255pages 3 1.3 A Guide to Chess Ed.Gerard & C. Advance from beginner Verviers 1969, 156 pages. 4 1.4 My System Aron Nimzovich Theory of chess to improve yourself 1973, 372 pages 5 1.5 Pawn Power in Chess Hans Kmoch Chess strategy using pawns. 1969, 300 pages 6 1.6 The Most Instructive Games Irving Chernev 62 annotated masterpieces of modern chess strat- of Chess Ever Played egy. 1972, 277 pages 7 1.7 The Development of Chess Dr. M. Euwe Annotated games explaining positional play, Style combination & analysis. 1968, 152pgs 8 1.8 Three Steps to Chess MasteryA.S. Suetin Examples of modern Grandmaster play to im- prove your playing strength. 1982, 188pgs 9 1.9 Grandmasters of Chess Harold C. Schonberg A history of modern chess through the lives of these great players. 1973, 302 pages 10 1.10 Grandmaster Preparation L. Polugayevsky How to prepare technically and psychologically for decisive encounters where everything is at stake. 1981, 232 pages 11 1.11 Grandmaster Performance L. Polugayevsky 64 games selected to give a clear impression of how victory is gained. 1984, 174 pages 12 1.12 Learn from the Grandmasters Raymond D. Keene A wide spectrum of games by a no. of players an- notated from different angles. 1975, 120 pgs 13 1.13 The Modern Chess Sacrifice Leonid Shamkovich ‘A thousand paths lead to delusion, but only one to the truth.’ 1980, 214 pages 14 1.14 Blunders & Brilliancies Ian Mullen and Moe Over 250 excellent exercises to asses your apti- Moss tude for brilliancy and blunder. -

Edsger Dijkstra: the Man Who Carried Computer Science on His Shoulders

INFERENCE / Vol. 5, No. 3 Edsger Dijkstra The Man Who Carried Computer Science on His Shoulders Krzysztof Apt s it turned out, the train I had taken from dsger dijkstra was born in Rotterdam in 1930. Nijmegen to Eindhoven arrived late. To make He described his father, at one time the president matters worse, I was then unable to find the right of the Dutch Chemical Society, as “an excellent Aoffice in the university building. When I eventually arrived Echemist,” and his mother as “a brilliant mathematician for my appointment, I was more than half an hour behind who had no job.”1 In 1948, Dijkstra achieved remarkable schedule. The professor completely ignored my profuse results when he completed secondary school at the famous apologies and proceeded to take a full hour for the meet- Erasmiaans Gymnasium in Rotterdam. His school diploma ing. It was the first time I met Edsger Wybe Dijkstra. shows that he earned the highest possible grade in no less At the time of our meeting in 1975, Dijkstra was 45 than six out of thirteen subjects. He then enrolled at the years old. The most prestigious award in computer sci- University of Leiden to study physics. ence, the ACM Turing Award, had been conferred on In September 1951, Dijkstra’s father suggested he attend him three years earlier. Almost twenty years his junior, I a three-week course on programming in Cambridge. It knew very little about the field—I had only learned what turned out to be an idea with far-reaching consequences. a flowchart was a couple of weeks earlier. -

A New Golden Age for Computer Architecture: Domain-Specific

A New Golden Age for Computer Architecture: Domain-Specific Hardware/Software Co-Design, Enhanced Security, Open Instruction Sets, and Agile Chip Development John Hennessy and David Patterson Stanford and UC Berkeley 13 June 2018 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3LVeEjsn8Ts 1 Outline Part I: History of Part II: Current Architecture - Architecture Challenges - Mainframes, Ending of Dennard Scaling Minicomputers, and Moore’s Law, Security Microprocessors, RISC vs CISC, VLIW Part III: Future Architecture Opportunities - Domain Specific Languages and Architecture, Open Architectures, Agile Hardware Development 2 IBM Compatibility Problem in Early 1960s By early 1960’s, IBM had 4 incompatible lines of computers! 701 ➡ 7094 650 ➡ 7074 702 ➡ 7080 1401 ➡ 7010 Each system had its own: ▪ Instruction set architecture (ISA) ▪ I/O system and Secondary Storage: magnetic tapes, drums and disks ▪ Assemblers, compilers, libraries,... ▪ Market niche: business, scientific, real time, ... IBM System/360 – one ISA to rule them all 3 Control versus Datapath ▪ Processor designs split between datapath, where numbers are stored and arithmetic operations computed, and control, which sequences operations on datapath ▪ Biggest challenge for computer designers was getting control correct Control Instruction Control Lines Condition?▪ Maurice Wilkes invented the idea of microprogramming to design the control unit of a PC processor* Datapath Registers Inst. Reg. ▪ Logic expensive vs. ROM or RAM ALU Busy? Address Data ▪ ROM cheaper than RAM Main Memory ▪ ROM much faster -

Simula Mother Tongue for a Generation of Nordic Programmers

Simula! Mother Tongue! for a Generation of! Nordic Programmers! Yngve Sundblad HCI, CSC, KTH! ! KTH - CSC (School of Computer Science and Communication) Yngve Sundblad – Simula OctoberYngve 2010Sundblad! Inspired by Ole-Johan Dahl, 1931-2002, and Kristen Nygaard, 1926-2002" “From the cold waters of Norway comes Object-Oriented Programming” " (first line in Bertrand Meyer#s widely used text book Object Oriented Software Construction) ! ! KTH - CSC (School of Computer Science and Communication) Yngve Sundblad – Simula OctoberYngve 2010Sundblad! Simula concepts 1967" •# Class of similar Objects (in Simula declaration of CLASS with data and actions)! •# Objects created as Instances of a Class (in Simula NEW object of class)! •# Data attributes of a class (in Simula type declared as parameters or internal)! •# Method attributes are patterns of action (PROCEDURE)! •# Message passing, calls of methods (in Simula dot-notation)! •# Subclasses that inherit from superclasses! •# Polymorphism with several subclasses to a superclass! •# Co-routines (in Simula Detach – Resume)! •# Encapsulation of data supporting abstractions! ! KTH - CSC (School of Computer Science and Communication) Yngve Sundblad – Simula OctoberYngve 2010Sundblad! Simula example BEGIN! REF(taxi) t;" CLASS taxi(n); INTEGER n;! BEGIN ! INTEGER pax;" PROCEDURE book;" IF pax<n THEN pax:=pax+1;! pax:=n;" END of taxi;! t:-NEW taxi(5);" t.book; t.book;" print(t.pax)" END! Output: 7 ! ! KTH - CSC (School of Computer Science and Communication) Yngve Sundblad – Simula OctoberYngve 2010Sundblad! -

Submission Data for 2020-2021 CORE Conference Ranking Process International Symposium on Formal Methods (Was Formal Methods Europe FME)

Submission Data for 2020-2021 CORE conference Ranking process International Symposium on Formal Methods (was Formal Methods Europe FME) Ana Cavalcanti, Stefania Gnesi, Lars-Henrik Eriksson, Nico Plat, Einar Broch Johnsen, Maurice ter Beek Conference Details Conference Title: International Symposium on Formal Methods (was Formal Methods Europe FME) Acronym : FM Rank: A Data and Metrics Google Scholar Metrics sub-category url: https://scholar.google.com.au/citations?view_op=top_venues&hl=en&vq=eng_theoreticalcomputerscienceposition in sub-category: 20+Image of top 20: ACM Metrics Not Sponsored by ACM Aminer Rank 1 Aminer Rank: 28Name in Aminer: World Congress on Formal MethodsAcronym or Shorthand: FMh-5 Index: 17CCF: BTHU: âĂŞ Top Aminer Cites: http://portal.core.edu.au/core/media/conf_submissions_citations/extra_info1804_aminer_top_cite.png Other Rankings Not aware of any other Rankings Conferences in area: 1. Formal Methods Symposium (FM) 2. Software Engineering and Formal Methods (SEFM), Integrated Formal Methods (IFM) 3. Fundamental Approaches to Software Engineering (FASE), NASA Formal Methods (NFM), Runtime Verification (RV) 4. Formal Aspects of Component Software (FACS), Automated Technology for Verification and Analysis (ATVA) 5. International Conference on Formal Engineering Methods (ICFEM), FormaliSE, Formal Methods in Computer-Aided Design (FMCAD), Formal Methods for Industrial Critical Systems (FMICS) 6. Brazilian Symposium on Formal Methods (SBMF), Theoretical Aspects of Software Engineering (TASE) 7. International Symposium On Leveraging Applications of Formal Methods, Verification and Validation (ISoLA) Top People Publishing Here name: Frank de Boer justification: h-index: 42 ( https://www.cwi.nl/people/frank-de-boer) Frank S. de Boer is senior researcher at the CWI, where he leads the research group on Formal Methods, and Professor of Software Correctness at Leiden University, The Netherlands. -

Wake up with CPS 006 Program Design and Methodology I Computer Science and Programming What Is Computer Science? Computer Scienc

Computer Science and Programming z Computer Science is more than programming ¾ The discipline is called informatics in many countries ¾ Elements of both science and engineering • Scientists build to learn, engineers learn to build Wake up with CPS 006 – Fred Brooks Program Design and Methodology I ¾ Elements of mathematics, physics, cognitive science, music, art, and many other fields z Computer Science is a young discipline Jeff Forbes ¾ Fiftieth anniversary in 1997, but closer to forty years of research and development ¾ First graduate program at CMU (then Carnegie Tech) in http://www.cs.duke.edu/courses/cps006/current 1965 http://www.cs.duke.edu/csed/tapestry z To some programming is an art, to others a science, to others an engineering discipline A Computer Science Tapestry 1.1 A Computer Science Tapestry 1.2 What is Computer Science? Computer Science What is it that distinguishes it from the z Artificial Intelligence thinking machines separate subjects with which it is related? z Scientific Computing weather, cars, heart, modelling What is the linking thread which gathers these z Theoretical CS analyze algorithms, models disparate branches into a single discipline? My answer to these questions is simple --- it is z Computational Geometry theory of animation, 3-D models the art of programming a computer. It is the art z Architecture hardware-software interface of designing efficient and elegant methods of z Software Engineering engineering, science getting a computer to solve problems, z Operating Systems the soul of the machine theoretical or practical, small or large, simple z Graphics from Windows to Hollywood or complex. z Many other subdisciplines C.A.R. -

Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames

Games of No Chance MSRI Publications Volume 29, 1996 Multilinear Algebra and Chess Endgames LEWIS STILLER Abstract. This article has three chief aims: (1) To show the wide utility of multilinear algebraic formalism for high-performance computing. (2) To describe an application of this formalism in the analysis of chess endgames, and results obtained thereby that would have been impossible to compute using earlier techniques, including a win requiring a record 243 moves. (3) To contribute to the study of the history of chess endgames, by focusing on the work of Friedrich Amelung (in particular his apparently lost analysis of certain six-piece endgames) and that of Theodor Molien, one of the founders of modern group representation theory and the first person to have systematically numerically analyzed a pawnless endgame. 1. Introduction Parallel and vector architectures can achieve high peak bandwidth, but it can be difficult for the programmer to design algorithms that exploit this bandwidth efficiently. Application performance can depend heavily on unique architecture features that complicate the design of portable code [Szymanski et al. 1994; Stone 1993]. The work reported here is part of a project to explore the extent to which the techniques of multilinear algebra can be used to simplify the design of high- performance parallel and vector algorithms [Johnson et al. 1991]. The approach is this: Define a set of fixed, structured matrices that encode architectural primitives • of the machine, in the sense that left-multiplication of a vector by this matrix is efficient on the target architecture. Formulate the application problem as a matrix multiplication. -

Reading List

EECS 101 Introduction to Computer Science Dinda, Spring, 2009 An Introduction to Computer Science For Everyone Reading List Note: You do not need to read or buy all of these. The syllabus and/or class web page describes the required readings and what books to buy. For readings that are not in the required books, I will either provide pointers to web documents or hand out copies in class. Books David Harel, Computers Ltd: What They Really Can’t Do, Oxford University Press, 2003. Fred Brooks, The Mythical Man-month: Essays on Software Engineering, 20th Anniversary Edition, Addison-Wesley, 1995. Joel Spolsky, Joel on Software: And on Diverse and Occasionally Related Matters That Will Prove of Interest to Software Developers, Designers, and Managers, and to Those Who, Whether by Good Fortune or Ill Luck, Work with Them in Some Capacity, APress, 2004. Most content is available for free from Spolsky’s Blog (see http://www.joelonsoftware.com) Paul Graham, Hackers and Painters, O’Reilly, 2004. See also Graham’s site: http://www.paulgraham.com/ Martin Davis, The Universal Computer: The Road from Leibniz to Turing, W.W. Norton and Company, 2000. Ted Nelson, Computer Lib/Dream Machines, 1974. This book is now very rare and very expensive, which is sad given how visionary it was. Simon Singh, The Code Book: The Science of Secrecy from Ancient Egypt to Quantum Cryptography, Anchor, 2000. Douglas Hofstadter, Goedel, Escher, Bach: The Eternal Golden Braid, 20th Anniversary Edition, Basic Books, 1999. Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig, Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, 2nd Edition, Prentice Hall, 2003. -

Intelligence Without Reason

Intelligence Without Reason Rodney A. Brooks MIT Artificial Intelligence Lab 545 Technology Square Cambridge, MA 02139, USA Abstract certain modus operandi over the years, which includes a particular set of conventions on how the inputs and out- Computers and Thought are the two categories puts to thought and reasoning are to be handled (e.g., that together define Artificial Intelligence as a the subfield of knowledge representation), and the sorts discipline. It is generally accepted that work in of things that thought and reasoning do (e.g,, planning, Artificial Intelligence over the last thirty years problem solving, etc.). 1 will argue that these conven has had a strong influence on aspects of com- tions cannot account for large aspects of what goes into puter architectures. In this paper we also make intelligence. Furthermore, without those aspects the va the converse claim; that the state of computer lidity of the traditional Artificial Intelligence approaches architecture has been a strong influence on our comes into question. I will also argue that much of the models of thought. The Von Neumann model of landmark work on thought has been influenced by the computation has lead Artificial Intelligence in technological constraints of the available computers, and particular directions. Intelligence in biological thereafter these consequences have often mistakenly be systems is completely different. Recent work in come enshrined as principles, long after the original im behavior-based Artificial Intelligence has pro petus has disappeared. duced new models of intelligence that are much closer in spirit to biological systems. The non- From an evolutionary stance, human level intelligence Von Neumann computational models they use did not suddenly leap onto the scene. -

Reshevsky Wins Playoff, Qualifies for Interzonal Title Match Benko First in Atlantic Open

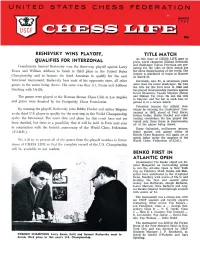

RESHEVSKY WINS PLAYOFF, TITLE MATCH As this issue of CHESS LIFE goes to QUALIFIES FOR INTERZONAL press, world champion Mikhail Botvinnik and challenger Tigran Petrosian are pre Grandmaster Samuel Reshevsky won the three-way playoff against Larry paring for the start of their match for Evans and William Addison to finish in third place in the United States the chess championship of the world. The contest is scheduled to begin in Moscow Championship and to become the third American to qualify for the next on March 21. Interzonal tournament. Reshevsky beat each of his opponents once, all other Botvinnik, now 51, is seventeen years games in the series being drawn. IIis score was thus 3-1, Evans and Addison older than his latest challenger. He won the title for the first time in 1948 and finishing with 1 %-2lh. has played championship matches against David Bronstein, Vassily Smyslov (three) The games wcre played at the I·lerman Steiner Chess Club in Los Angeles and Mikhail Tal (two). He lost the tiUe to Smyslov and Tal but in each case re and prizes were donated by the Piatigorsky Chess Foundation. gained it in a return match. Petrosian became the official chal By winning the playoff, Heshevsky joins Bobby Fischer and Arthur Bisguier lenger by winning the Candidates' Tour as the third U.S. player to qualify for the next step in the World Championship nament in 1962, ahead of Paul Keres, Ewfim Geller, Bobby Fischer and other cycle ; the InterzonaL The exact date and place for this event havc not yet leading contenders. -

OFFLINE GAMING VS CLOUD GAMING (ONLINE GAMING) Mr

ISSN: 0974-3308, VOL. 11, NO. 2 DECEMBER 2018 @ SRIMCA 99 OFFLINE GAMING VS CLOUD GAMING (ONLINE GAMING) Mr. Amit Khatri Abstract—Games has always been a major source of entertainment in every generation and so exiting their history is, because it has various factor involved like Video Games Industry and various generations of video games. Due to improvements in graphics, a revolution has occurred in computer games. Storage for Video Games has always been a problem whether it is a Gaming Console or a PC but has been resolved generation by generation. Games also attracted the uninterested audience. Offline Gaming has been very popular for a year but has various drawbacks. Cloud Gaming is the resolution against Offline Gaming. This paper talks about how Cloud Gaming is taking place of Offline Gaming with much powerful hardware systems and processes. Keywords—Gaming, Cloud Gaming, Gaming PC, Gaming Console, Video Games. I. GAMING AND ITS HISTORY Computerized game playing, whether it is over a personal computer, mobile phone or a video game console can be referred to as Gaming. An individual who plays video games is recognized as a gamer [1]. In every generation of technology evolution, graphics of the game have been improved. When we think the history of video games we usually think of games like Tic- tac-toe, Tetris, Pacman, pong and many more but now these games use graphics seems like reality. In the 1950s, People can’t think of playing card games such as Solitaire, Blackjack, Hearts, Spider Solitaire and so on, on tv or computer but now the stage has reached more ahead from that [1]. -

Should Chess Players Learn Computer Security?

1 Should Chess Players Learn Computer Security? Gildas Avoine, Cedric´ Lauradoux, Rolando Trujillo-Rasua F Abstract—The main concern of chess referees is to prevent are indeed playing against each other, instead of players from biasing the outcome of the game by either collud- playing against a little girl as one’s would expect. ing or receiving external advice. Preventing third parties from Conway’s work on the chess grandmaster prob- interfering in a game is challenging given that communication lem was pursued and extended to authentication technologies are steadily improved and miniaturized. Chess protocols by Desmedt, Goutier and Bengio [3] in or- actually faces similar threats to those already encountered in der to break the Feige-Fiat-Shamir protocol [4]. The computer security. We describe chess frauds and link them to their analogues in the digital world. Based on these transpo- attack was called mafia fraud, as a reference to the sitions, we advocate for a set of countermeasures to enforce famous Shamir’s claim: “I can go to a mafia-owned fairness in chess. store a million times and they will not be able to misrepresent themselves as me.” Desmedt et al. Index Terms—Security, Chess, Fraud. proved that Shamir was wrong via a simple appli- cation of Conway’s chess grandmaster problem to authentication protocols. Since then, this attack has 1 INTRODUCTION been used in various domains such as contactless Chess still fascinates generations of computer sci- credit cards, electronic passports, vehicle keyless entists. Many great researchers such as John von remote systems, and wireless sensor networks.