Jordan's Principle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Background and Importance First Nations Children and Youth Deserve

OHCHR STUDY ON CHILDREN’S RIGHTS TO HEALTH – HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL RESOLUTION 19/37 SUBMISSION FROM THE FIRST NATIONS CHILD AND FAMILY CARING SOCIETY OF CANADA Background and Importance First Nations1 children and youth deserve the same chance to succeed as all other children. As set upon by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Indigenous children have the right to adequate health and to culturally based health services and without discrimination (UNCRC, Article 2, 24; UNDRIP, Article 21, 24). However, the reality of First Nations children and youth who live on reserves is often one of poverty, poor drinking water and lack of access to proper healthcare among other health discrepancies, leaving First Nations children and youth behind other Canadian children. These daily challenges are often rooted in Canada’s colonial history and further amplified by government policies and procedures, a failure to address large scale challenges such as poverty which exacerbate poor health conditions, and programs and services that do not reflect the distinct needs of First Nations children and families. Further, the Canadian Government provides inequitable health, child welfare and education services and funding undermining the rights, safety and wellbeing of First Nations children (Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples [RCAP], 1996; Auditor General of Canada, 2008; Office of the Provincial Advocate, 2010). Despite these challenges to health, First Nations communities are taking steps of redress to promote healthy outcomes for the children and youth and the generations to come. 1 First Nations refers to one of the three Aboriginal groups in Canada as per the Federal Government definition. -

Redress Movements in Canada

Editor: Marlene Epp, Conrad Grebel University College University of Waterloo Series Advisory Committee: Laura Madokoro, McGill University Jordan Stanger-Ross, University of Victoria Sylvie Taschereau, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières Copyright © the Canadian Historical Association Ottawa, 2018 Published by the Canadian Historical Association with the support of the Department of Canadian Heritage, Government of Canada ISSN: 2292-7441 (print) ISSN: 2292-745X (online) ISBN: 978-0-88798-296-5 Travis Tomchuk is the Curator of Canadian Human Rights History at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and holds a PhD from Queen’s University. Jodi Giesbrecht is the Manager of Research & Curation at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, and holds a PhD from the University of Toronto. Cover image: Japanese Canadian redress rally at Parliament Hill, 1988. Photographer: Gordon King. Credit: Nikkei National Museum 2010.32.124. REDRESS MOVEMENTS IN CANADA Travis Tomchuk & Jodi Giesbrecht Canadian Museum for Human Rights All rights reserved. No part of this publication maybe reproduced, in any form or by any electronic ormechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Canadian Historical Association. Ottawa, 2018 The Canadian Historical Association Immigration And Ethnicity In Canada Series Booklet No. 37 Introduction he past few decades have witnessed a substantial outpouring of Tapologies, statements of regret and recognition, commemorative gestures, compensation, and related measures -

EXPERIENCES of RACIALIZED COMMUNITIES DURING COVID-19 Reflections and a Way Forward

may 2021 EXPERIENCES OF RACIALIZED COMMUNITIES DURING COVID-19 Reflections and a way forward 1 CONTENTS Land Acknowledgment 3 Research Team 4 Executive Summary 5 Recommendations: The Path to Recovery 9 Introduction 12 Methodology 12 1. Demographic Profile 14 Distribution by Race 14 Gender Distribution 15 Age Distribution 15 Distribution by Employment Status 15 Distribution by Income 16 Distribution by Highest Level of Education 17 2. Community Perceptions 18 Trust in Government and Community 18 Community Response 19 3. Wellbeing Dimensions 22 Physical Wellbeing 22 Financial Wellbeing 23 Spiritual Wellbeing 24 Emotional Wellbeing 25 Social Wellbeing 28 4. The Power of Social Capital 31 Conclusion 33 Researcher Biographies 37 Community Organizations 42 Special Mention 46 2 Land Acknowledgment The Canadian Arab Institute acknowledges that we live and work on the traditional territory of many nations including the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, the Haudenosaunee and the Wendat peoples. Brock University acknowledges the land on which we gather is the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe peoples, many of whom continue to live and work here today. This territory is covered by the Upper Canada Treaties and is within the land protected by the Dish with One Spoon Wampum Agreement. Today this gathering place is home to many First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples and acknowledging reminds us that our great standard of living is directly related to the resources and friendship of Indigenous people. 3 Research Team Principal Co-investigator Dr. Gervan Fearon Dr. Walid Hejazi President, Brock University Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto Lead Operational Researcher Dr. -

There's No Crisis in Thunder Bay and It's 'Business As Usual' Says Acting

6/8/2017 There’s no crisis in Thunder Bay and it’s ‘business as usual’ says acting police chief APTN NewsAPTN News (http://aptn.ca/news) There’s no crisis in Thunder Bay and it’s ‘business as usual’ says acting police chief National News (http://aptnnews.ca/category/nationalnews/) | June 7, 2017 by Kenneth Jackson (http://aptnnews.ca/author/kjackson/) Attributed to: | 4 Comments (http://aptnnews.ca/2017/06/07/theresnocrisisinthunderbayanditsbusinessasusualsaysactingpolicechief/#comments) Recommend Share 1.4K people recommend this. Sign Up to see what your friends recommend. Tweet (http://aptnnews.ca/wp content/uploads/2017/06/thunderbay police.jpg) Kenneth Jackson APTN National News Thunder Bay’s police chief has been charged by the OPP for breach of trust. The entire Thunder Bay police force is under a systemic review by the provincial police watchdog for how it treats Indigenous people. The Thunder Bay police services board is also under a separate investigation. Seven First Nations youth have died in the waterways, including two last month, since 2000. An inquest into several of those deaths, and others, wrapped up last year. There are cases of adult First Nation people dying in the waterways and police accused of not properly investigating. There have been calls from First Nation leaders for change, including a media conference in Toronto where Thunder Bay police were accused of treating the deaths as just another “drunk Indian.” But despite all that Thunder Bay police say they have it under control. -

Objectives of the Study

Socioeconomic Profiles of Immigrants in the Four Atlantic provinces - Phase II: Focus on Vibrant Communities Ather H. Akbari Saint Mary’s University, Halifax Wimal Rankaduwa University of Prince Edward Island, Charlottetown December 2008 Research and Evaluation The funding for this research paper has been provided by Citizenship and Immigration Canada as part of its contribution to the Atlantic Population Table, a collaborative initiative between Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency, Citizenship and Immigration Canada, Human Resources and Skills Development Canada and the provincial governments of Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island. This document expresses the views of the authors and does not represent the official position of Citizenship and Immigration Canada or the position of the Atlantic Population Table. Ci4-40/1-2010E-PDF 978-1-100-15926-3 Table of contents Some Definitions Used in this Study ............................................................... v Executive Summary ................................................................................... vi Introduction ............................................................................................ 1 Methodology and sources of data ............................................................................... 2 Some general trends of immigrant inflows and of international students in Atlantic Canada .................................................................................................. 3 Immigrant inflows in -

The Arab Community in Canada

Catalogue no. 89-621-XIE — No. 9 ISSN: 1719-7376 ISBN: 978-0-662-46473-0 Analytical Paper Profiles of Ethnic Communities in Canada The Arab Community in Canada 2001 by Colin Lindsay Social and Aboriginal Statistics Division 7th Floor, Jean Talon Building, Ottawa, K1A 0T6 Telephone: 613-951-5979 How to obtain more information For information about this product or the wide range of services and data available from Statistics Canada, visit our website at www.statcan.ca or contact us by e-mail at [email protected] or by phone from 8:30am to 4:30pm Monday to Friday at: Toll-free telephone (Canada and the United States): Enquiries line 1-800-263-1136 National telecommunications device for the hearing impaired 1-800-363-7629 Fax line 1-877-287-4369 Depository Services Program enquiries line 1-800-635-7943 Depository Services Program fax line 1-800-565-7757 Statistics Canada national contact centre: 1-613-951-8116 Fax line 1-613-951-0581 Information to access the product This product, catalogue no. 89-621-XIE, is available for free in electronic format. To obtain a single issue, visit our website at www.statcan.ca and select Publications. Standards of service to the public Statistics Canada is committed to serving its clients in a prompt, reliable and courteous manner. To this end, the Agency has developed standards of service which its employees observe in serving its clients. To obtain a copy of these service standards, please contact Statistics Canada toll free at 1-800-263-1136. The service standards are also published on www.statcan.ca under About us > Providing services to Canadians. -

Cricket As a Diasporic Resource for Caribbean-Canadians by Janelle Beatrice Joseph a Thesis Submitted in Conformity with the Re

Cricket as a Diasporic Resource for Caribbean-Canadians by Janelle Beatrice Joseph A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Exercise Sciences University of Toronto © Janelle Beatrice Joseph 2010 Cricket as a Diasporic Resource for Caribbean-Canadians Janelle Beatrice Joseph Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Exercise Sciences University of Toronto 2010 Abstract The diasporic resources and transnational flows of the Black diaspora have increasingly been of concern to scholars. However, the making of the Black diaspora in Canada has often been overlooked, and the use of sport to connect migrants to the homeland has been virtually ignored. This study uses African, Black and Caribbean diaspora lenses to examine the ways that first generation Caribbean-Canadians use cricket to maintain their association with people, places, spaces, and memories of home. In this multi-sited ethnography I examine a group I call the Mavericks Cricket and Social Club (MCSC), an assembly of first generation migrants from the Anglo-Caribbean. My objective to “follow the people” took me to parties, fundraising dances, banquets, and cricket games throughout the Greater Toronto Area on weekends from early May to late September in 2008 and 2009. I also traveled with approximately 30 MCSC members to observe and participate in tours and tournaments in Barbados, England, and St. Lucia and conducted 29 in- depth, semi-structured interviews with male players and male and female supporters. I found that the Caribbean diaspora is maintained through liming (hanging out) at cricket matches and social events. Speaking in their native Patois language, eating traditional Caribbean foods, and consuming alcohol are significant means of creating spaces in which Caribbean- Canadians can network with other members of the diaspora. -

C O M Mu N Iqu É | 20 20

communiqué | 2020 MISSION TABLE OF CONTENTS APTN is sharing our Peoples’ journey, 2 Message from Our Chairperson celebrating our cultures, inspiring our 4 Message from Our CEO children and honouring the wisdom 6 Year in Review 20 Years of APTN of our Elders. 8 10 Indigenous Production 20 Our People 26 Understanding Our Audience ABOUT APTN 30 Advertising The launch of APTN on Sept. 1, 1999 represented a 36 Setting the Technological Pace significant milestone for Indigenous Peoples across 40 Community Relations & Sponsorships Canada. The network has since become an important 46 Covering the Stories that Others Won’t source of entertainment, news and educational programming for nearly 11 million households across 54 Conditions of Licence Canada. Since television broadcasts began reaching 62 Programming the Canadian North over 30 years ago, the dream of 80 APTN Indigenous Day Live a national Indigenous television network has become Appendix A | Independent Production Activity a reality. The rest, as they say, is broadcast history. (Original Productions) 2019–2020 APTN’s fiscal year runs from Sept. 1, 2019 to Aug. 31, 2020. APTN COMMUNIQUÉ 2020 1 MESSAGE FROM OUR CHAIRPERSON Jocelyn Formsma WACHIYA, What a year it has been for APTN. Like the From the outset, Monika impressed In addition to selecting a new operating a charity continue to will also assist the Dadan Sivunivut us with her passion for APTN and CEO, the board also dealt with be followed accordingly. Animiki Board of Directors in identifying previous 20 years of our history, we have once supporting the important work some restructuring as we finalized See Digital Production, Animiki a permanent CEO. -

Political Science Graduate Student Journal

Political Science Graduate Student Journal Volume V In the Age of Reconciliation: Persisting Settler Colonialism in Canada Concordia University Department of Political Science Fall 2016 Political Science Graduate Student Journal Vol. 5 Political Science Graduate Student Journal Volume V In the Age of Reconciliation: Persisting Settler Colonialism in Canada Department of Political Science Concordia University Montréal, Québec, Canada 2016-2017 1 Political Science Graduate Student Journal Vol. 5 2 Political Science Graduate Student Journal Vol. 5 In the Age of Reconciliation: Persisting Settler Colonialism in Canada Volume V Editorial Board Coordinating Editor Andréanne Nadeau Editorial and Review Committee Fatima Hirji Tajdin Johanna Sturtewagen Vindya Seneviratne Janet Akins Faculty Advisor Dr. Daniel Salée 5th Annual Graduate Student Conference Keynote Speaker Dr. Martin Papillon Panel Discussants Dr. Brooke Jeffrey Dr. Mireille Paquet Dr. Stéphanie Paterson Concluding Remarks Dr. Daniel Salée 3 Political Science Graduate Student Journal Vol. 5 4 Political Science Graduate Student Journal Vol. 5 In the Age of Reconciliation: Persisting Settler Colonialism in Canada Table of Contents Foreword 7 Foreword (Following) 8 Settler Colonialism And The Plan Nord In Nunavik 13 Settlers’ Relations With Indigenous Peoples: The Role Of Education In Reconciling With Our Past 37 Canada’s Missing And Murdered Indigenous Women: The Trouble With Media Representation 67 Persisting Impacts Of Colonial Constructs: Social Construction, Settler Colonialism, And The Canadian State’s (In)Action To The Missing And Murdered Indigenous Women Of Canada 85 5 Political Science Graduate Student Journal Vol. 5 6 Political Science Graduate Student Journal Vol. 5 Foreword This journal began with the Department of Political Science 5th Annual Graduate Student Conference, entitled “Because It’s 2015”: Minorities and Representation. -

2019 MISSION APTN Is Sharing Our Peoples’ Journey, Celebrating Our Cultures, Inspiring Our Children and Honouring the Wisdom of Our Elders

COMMUNIQUÉ 2019 MISSION APTN is sharing our Peoples’ journey, celebrating our cultures, inspiring our children and honouring the wisdom of our Elders. ABOUT APTN The launch of APTN on Sept. 1, 1999 represented a significant milestone for Indigenous Peoples across Canada. The network has since become an important entertainment, news and educational programming choice for nearly 11 million households across Canada. Since APTN had its beginnings in the Canadian North more than 30 years ago, the dream of a national Indigenous television network has become a reality. The rest, as they say, is broadcast history. APTN’s fiscal year runs from Sept. 1, 2018 to Aug. 31, 2019. APTN COMMUNIQUÉ 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Message from Our Chairperson 4 Message from Our CEO 6 Year in Review 8 Indigenous Production 18 Our People 24 Understanding Our Audience 28 Advertising 32 Setting the Technological Pace 36 Community Relations & Sponsorships 40 Covering the Stories that Others Won’t 44 Conditions of Licence 52 Programming 72 APTN Indigenous Day Live 76 APTN’s Extended Family Appendix A | Independent Production Activity (Original Productions) 2018–2019 Cover art by Mike Valcourt. 1 MESSAGE FROM OUR CHAIRPERSON JOCELYN FORMSMA WACHIYA, From the very beginning, APTN’s mission This ensures we are better able to meet industry demands while still has been to share our Peoples’ journey, delivering high-quality, relevant celebrate our cultures, inspire our children content to our audiences. We demonstrated our commitment and honour the wisdom of our Elders. to audiences when we launched Nouvelles Nationales d’APTN in late Over the years, our mission has remained August. -

Volume 3: Population Groups and Ethnic Origins

Ethnicity SEriES A Demographic Portrait of Manitoba Volume 3 Population Groups and Ethnic Origins Sources: Statistics Canada. 2001 and 2006 Censuses – 20% Sample Data Publication developed by: Statistics Canada information is used with the permission of Statistics Canada. Manitoba Immigration and Users are forbidden to copy the data and redisseminate them, in an original or Multiculturalism modified form, for commercial purposes, without permission from Statistics And supported by: Canada. Information on the availability of the wide range of data from Statistics Canada can be obtained from Statistics Canada’s Regional Offices, its World Wide Citizenship and Immigration Canada Web site at www.statcan.gc.ca, and its toll-free access number 1-800-263-1136. Contents Introduction 2 Canada’s Population Groups 3 manitoba’s Population Groups 4 ethnic origins 5 manitoba Regions 8 Central Region 10 Eastern Region 13 Interlake Region 16 Norman Region 19 Parklands Region 22 Western Region 25 Winnipeg Region 28 Winnipeg Community Areas 32 Assiniboine South 34 Downtown 36 Fort Garry 38 Inkster 40 Point Douglas 42 River East 44 River Heights 46 Seven Oaks 48 St. Boniface 50 St. James 52 St. Vital 54 Transcona 56 Vol. 3 Population Groups and Ethnic Origins 1 Introduction Throughout history, generations of The ethnicity series is made up of three volumes: immigrants have arrived in Manitoba to start a new life. Their presence is 1. Foreign-born Population celebrated in our communities. Many This volume presents the population by country of birth. It focuses on the new immigrants, and a large number foreign-born population and its recent regional distribution across Manitoba. -

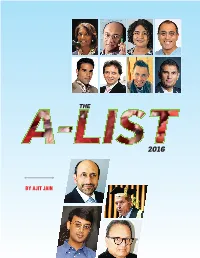

BY AJIT JAIN IFC-IBC Final Layout 1 12/23/2015 11:28 PM Page 1 1-3 Title Page Layout 1 1/5/2016 6:14 AM Page 1

cover and back cover final_Layout 1 1/4/2016 10:41 PM Page 2 THE 2016 N N BY AJIT JAIN IFC-IBC final_Layout 1 12/23/2015 11:28 PM Page 1 1-3 Title page_Layout 1 1/5/2016 6:14 AM Page 1 THE A-LIST 2016 N N By Ajit Jain 1-3 Title page_Layout 1 1/5/2016 6:14 AM Page 2 1-3 Title page_Layout 1 1/5/2016 6:14 AM Page 3 Contents p. 06;09 INTRODUCTION p. 10;13 INDO;CANADIANS IN THE FEDERAL CABINET Amarjeet Sohi, Bardish Chagger, Harjit Singh Sajjan, Navdeep Bains p. 14;58 INDO;CANADIAN HIGH ACHIEVERS Abhya Kulkarni, Anil Arora, Anil Kapoor, Arun Chokalingam, Baldev Nayar, Chitra Anand, Deepak Gupta, Desh Sikka, Dilip Soman, Dolly Dastoor, Gagan Bhalla, Gopal Bhatnagar, Hari Krishnan, Harjeet Bhabra, Indira Naidoo-Harris, Jagannath Prasad Das, Kasi Rao, Krish Suthanthiran, Lalita Krishna, Manasvi Noel, Manjul Bhargava, Navin Nanda, Omar Sachedina, Panchal Mansaram, Paul Shrivastava, Paviter Binning, Pooja Handa, Prabhat Jha, Prem Watsa, Ram Jakhu, Raminder Dosanjh, Renu Mandhane, Rohinton Mistry, Sajeev John, Sanjeev Sethi, Soham Ajmera, Steve Rai, Sunder Singh, Veena Rawat, Vijay Bhargava,Vikam Vij p. 60;62 THE A-LIST FRIENDS OF INDIA Gary Comerford, Mathieu Boisvert, Patrick Brown 2016 p. 64;69 INDO;CANADIAN INSTITUTIONS AIM for SEVA Canada-India Center of Excellence in Science, Technology, Trade and Policy Canada India Foundation Center for South Asian Studies Child Haven International Shastri Indo-Canadian Institute EDITOR AND PUBLISHER Ajit Jain DESIGN Angshuman De PRINTED AT Sherwood Design and Print, 131, Whitmore Road, #18 Woodbridge, Ontario,L4L 6E4, Canada EDITORIAL AND PRODUCTION Crossmedia Advisory Services Inc.