Understanding Multiple Perspectives of the Sacred Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nepal HIDDEN VALLEYS of KHUMBU TREK & BABAI RIVER

Nepal HIDDEN VALLEYS OF KHUMBU TREK & BABAI RIVER CAMP 16 DAYS HIMALAYAN CLIMBS We run ethical, professionally led climbs. Our operations focuses foremost on responsible tourism: Safety: All guides carry satellite phones in case of an emergency or helicopter rescue. Carried on all treks are comprehensive emergency kits. High altitude trips require bringing a Portable Altitude Chamber (PAC) and supplemental oxygen. Responsibility: All rubbish is disposed of properly, adhering to ‘trash in trash out’ practices. Any non-biodegradable items are taken back to the head office to make sure they’re disposed of properly. To help the local economy all vegetables, rice, kerosene, chicken, and sheep is bought from local villages en route to where guests are trekking. Teams: Like most of our teams, the porters have been working with us for almost 10 years. Porters are provided with adequate warm gear and tents, are paid timely, and are never overloaded. In addition, porters are insured and never left on the mountain. In fact, most insurance benefits are extended to their families as well. Teams are paid above industry average and training programs and English courses are conducted in the low seasons; their knowledge goes beyond just trekking but also into history, flora, fauna, and politics. Client Experience: Our treks proudly introduce fantastic food. Cooks undergo refresher courses every season to ensure that menus are new and exciting. All food is very hygienically cared for. By providing private toilets, shower tents, mess tents, tables, chairs, Thermarest mattresses, sleeping bags, liners and carefully choosing campsites for location in terms of safety, distance, space, availability of water and the views – our guests are sure to have a comfortable and enjoyable experience! SAFETY DEVICES HIDDEN VALLEYS OF KHUMBU TREK & BABAI RIVER CAMP Overview Soaring to an ultimate 8,850m, Mt Everest and its buttress the Lhotse wall dominates all other peaks in view and interest. -

National Parks and Iccas in the High Himalayan Region of Nepal: Challenges and Opportunities

[Downloaded free from http://www.conservationandsociety.org on Tuesday, June 11, 2013, IP: 129.79.203.216] || Click here to download free Android application for this journal Conservation and Society 11(1): 29-45, 2013 Special Section: Article National Parks and ICCAs in the High Himalayan Region of Nepal: Challenges and Opportunities Stan Stevens Department of Geosciences, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, USA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In Nepal, as in many states worldwide, national parks and other protected areas have often been established in the customary territories of indigenous peoples by superimposing state-declared and governed protected areas on pre-existing systems of land use and management which are now internationally considered to be Indigenous Peoples’ and Community Conserved Territories and Areas (ICCAs, also referred to Community Conserved Areas, CCAs). State intervention often ignores or suppresses ICCAs, inadvertently or deliberately undermining and destroying them along with other aspects of indigenous peoples’ cultures, livelihoods, self-governance, and self-determination. Nepal’s high Himalayan national parks, however, provide examples of how some indigenous peoples such as the Sharwa (Sherpa) of Sagarmatha (Mount Everest/Chomolungma) National Park (SNP) have continued to maintain customary ICCAs and even to develop new ones despite lack of state recognition, respect, and coordination. The survival of these ICCAs offers Nepal an opportunity to reform existing laws, policies, and practices, both to honour UN-recognised human and indigenous rights that support ICCAs and to meet International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) standards and guidelines for ICCA recognition and for the governance and management of protected areas established in indigenous peoples’ territories. -

21 Days -Everest High Altitude Transverse - Two High Passes

Full Itinerary & Trip Details 21 Days -Everest High Altitude Transverse - Two High Passes BEST SELECTION BEST PRICES TRUSTED PAYMENTS 21 Days -Everest High Altitude https://www.tourradar.com/t/171364 Transverse - Two High Passes Trip Overview PRICE STARTING FROM DURATION IDEAL AGE $2,099 21 days 15 to 85 year olds STARTS IN ENDS IN Kathmandu Kathmandu STYLE Mountain Hikes OPERATOR TOUR CODE Serene Himalaya Treks and Expedition #171364 21 Days -Everest High Altitude https://www.tourradar.com/t/171364 Transverse - Two High Passes Itinerary Introduction This is the ultimate Everest Circuit Trek meant for only the truly adventurous as this trail takes us from Thame to Gokyo over Renjo La pass (5345m) and Gokyo to EBC over Cho La pass (5420m). The summit of Mt. Everest is the highest elevation above sea level on planet Earth, and its name has entered the language as a metaphor for the ultimate of anything. The Everest transverse trek travels to the remotest parts of the Khumbu and visits all the main valleys of the region. It is one of the best trekking routes in Nepal and is very challenging and famous trail with unforgettable memories of Himalayan experience. You can explore fascinating Sherpa villages and visit the Buddhist monasteries. The Everest high altitude transverse is an ultimate three weeks trekking experience for those who wish to visit Everest Base Camp. The route is longer and more challenging as it crosses two high passes, the Renjo la (5345m) and the Cho La (5420m) and takes to the Everest view point of Kala Patthar (5545m). -

The Sherpa and the Snowman

THE SHERPA AND THE SNOWMAN Charles Stonor the "Snowman" exist an ape DOESlike creature dwelling in the unexplored fastnesses of the Himalayas or is he only a myth ? Here the author describes a quest which began in the foothills of Nepal and led to the lower slopes of Everest. After five months of wandering in the vast alpine stretches on the roof of the world he and his companions had to return without any demon strative proof, but with enough indirect evidence to convince them that the jeti is no myth and that one day he will be found to be of a a very remarkable man-like ape type thought to have died out thousands of years before the dawn of history. " Apart from the search for the snowman," the narrative investigates every aspect of life in this the highest habitable region of the earth's surface, the flora and fauna of the little-known alpine zone below the snow line, the unexpected birds and beasts to be met with in the Great Himalayan Range, the little Buddhist communities perched high up among the crags, and above all the Sherpas themselves that stalwart people chiefly known to us so far for their gallant assistance in climbing expeditions their yak-herding, their happy family life, and the wav they cope with the bleak austerity of their lot. The book is lavishly illustrated with the author's own photographs. THE SHERPA AND THE SNOWMAN "When the first signs of spring appear the Sherpas move out to their grazing grounds, camping for the night among the rocks THE SHERPA AND THE SNOWMAN By CHARLES STONOR With a Foreword by BRIGADIER SIR JOHN HUNT, C.B.E., D.S.O. -

May 2013 India Review Ambassador’S PAGE America Needs More High-Skilled Worker Visas a Generous Visa Policy for Highly Skilled Workers Would Help Everyone

A Publication of the Embassy of India, Washington, D.C. May 1, 2013 I India RevieI w Vol. 9 Issue 5 www.indianembassy.org IMFC Finance Ministers and Bank Governors during a photo-op at the IMF Headquarters in Washington, D.C. on April 20. Overseas capital best protected in India — Finance Minister P. Chidambaram n India announces n scientist U.R. Rao n Pran honored incentives to boost inducted into with Dadasaheb exports Satellite Hall of Fame Phalke award Ambassador’s PAGE India is ready for U.S. natural gas There is ample evidence that the U.S. economy will benefit if LNG exports are increased he relationship between India and the United States is vibrant and growing. Near its T heart is the subject of energy — how to use and secure it in the cleanest, most efficient way possible. The India-U.S. Energy Dialogue, established in 2005, has allowed our two countries to engage on many issues. Yet as India’s energy needs con - tinue to rise and the U.S. looks to expand the marketplace for its vast cache of energy resources, our partner - ship stands to be strengthened even facilities and ports to distribute it macroeconomic scenarios, and under further. globally. every one of them the U.S. economy Despite the global economic slow - There is a significant potential for would experience a net benefit if LNG down, India’s economy has grown at a U.S. exports of LNG to grow expo - exports were increased. relatively brisk pace over the past five nentially. So far, however, while all ter - A boost in LNG exports would have years and India is now the world’s minals in the U.S. -

Landscape Change in Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) National Park, Khumbu, Nepal

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 17 Number 2 Himalayan Research Bulletin: Article 16 Solukhumbu and the Sherpa 1997 Landscape Change in Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) National Park, Khumbu, Nepal Alton C. Byers Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Byers, Alton C.. 1997. Landscape Change in Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) National Park, Khumbu, Nepal. HIMALAYA 17(2). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol17/iss2/16 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Landscape Change in Sagarmatha (Mt. Everest) National Park, Khumbu, Nepal Alton C. Byers The Mountain Institute This study uses repeat photography as the primary Introduction research tool to analyze processes of physical and Repeat photography, or precise replication and cultural landscape change in the Khumbu (M!. Everest) interpretation of historic landscape scenes, is an region over a 40-year period (1955-1995). The study is analytical tool capable of broadly clarifying the patterns a continuation of an on-going project begun by Byers in and possible causes of contemporary landscapellanduse 1984 that involves replication of photographs originally changes within a given region (see: Byers 1987a1996; taken between 1955-62 from the same five photo 1997). As a research tool, it has enjoyed some utility points. The 1995 investigation reported here provided in the United States during the past thirty years (see: the opportunity to expand the photographic data base Byers 1987b; Walker 1968; Heady and Zinke 1978; from five to 26 photo points between Lukla (2,743 m) Gruell 1980; Vale, 1982; Rogers et al. -

European Bulletin of Himalayan Research (EBHR)

On Local Festival Performance: The Sherpa Dumji in a world of dramatically increasing uncertainties1 Eberhard Berg It is important to remember, however, that Tibetan Buddhism, especially the form followed by the Rnying ma pa, is intended first and foremost to be pragmatic (...). The explanation for the multiplicity of metaphors and tutelary deities lies in the fact that there must be a practice suited to every sentient creature somewhere. Forms or metaphors that were relevant yesterday may lose their efficacy in the changed situation of today. E.G. Smith (2001:240) The Sherpas are a small, ethnically Tibetan people who live at high altitudes in the environs of Mt. Everest in Solu-Khumbu, a relatively remote area in the north eastern part of the “Hindu Kingdom of Nepal”. Traditionally, their economy has combined agriculture with herding and local as well as long- distance trade. Since the middle of the 20th century they have been successfully engaged in the trekking and mountaineering boom. Organised in patrilineal clans, they live in nuclear family households in small villages, hamlets, and isolated homesteads. Property in the form of herds, houses and land is owned by nuclear families. Among the Sherpas, Dumji, the famous masked dance festival, is held annually in the village temple of only eight local communities in Solu- Khumbu. According to lamas and laypeople alike Dumji represents the most important village celebration in the Sherpas’ annual cycle of ceremonies. The celebration of the Dumji festival is reflective of both Tibetan Buddhism and its supremacy over authochtonous belief systems, and the way a local community constructs, reaffirms and represents its own distinct local 1 I would like to thank the Sherpa community of the Lamaserwa clan, to their village lama, Lama Tenzing, who presides over the Dumji festival, and the ritual performers who assist him, and the Lama of Serlo Gompa, Ven. -

Everest View Point & Tengboche Trek

Xtreme Climbers Treks And Expedition Pvt Ltd Website:https://xtremeclibers.com Email:[email protected] Phone No:977 - 9801027078,977 - 9851027078 P.O.Box:9080, Kathmandu, Nepal Address: Bansbari, Kathmandu, Nepal Everest View Point & Tengboche Trek Introduction Everest view point & Tengboche trek. “The adventure of a lifetime, a journey” Without a doubt, one of the most renowned travel destinations in the world. For adventure travelers an exciting opportunity to be at the foot of the world's highest mountain – Mount Everest (8,848m/29,029ft) and World Heritage Site as well. those whose dreams soar higher than even the clouds. Miles from cars, conveniences, and daily luxuries, you'll saturate your spirit in natural beauty and stretch your personal endurance beyond what you thought possible. Your trek to Everest View point and Tengboche or Deboche at 3,860m. to the base of the world's tallest mountain will takes you over suspension bridges spanning chasms of thin air, through hidden Buddhist monasteries, and into the heart of the warm, rugged Sherpa culture. During this trip you will observe the incredible panoramic view of Mount Everest surrounded by adjoining mountains. The specialty of this short trip is the closest view of, Mt Everest (8,848m/29, 028ft), Lhotse (8,516 m/24,940 ft), Nuptse (7,855m/25,772 ft, Makalu (8,463m/27758ft), Pumori (7,161m/23488ft), Tharmarsarku (6,623m/21723ft), Mt. Amadablam The path begins in ancient Kathmandu, where you'll acclimate and explore the city at your leisure while anticipating your ascent. 3,860m. and many more… Facts Altitude: 3,860m. -

TO DO!2001 Contest Socially Responsible Tourism Award Winner TENGBOCHE DEVELOPMENT PROJECT

TO DO!2001 Contest Socially Responsible Tourism Award Winner TENGBOCHE DEVELOPMENT PROJECT represented by the Honorary Ngawang Tenzin Zangpo Rinpoche, the Abbot of Tengboche Monastery Michael Schmitz Project Manager Tengboche Monastery, Community of Khumjung, Solu-Khumbu District, Nepal Rationale for the Award by Klaus Betz “Our hands are big but our arms are short.” Tibetan saying 1. INTRODUCTION Investigations into the candidacy of the TENGBOCHE DEVELOPMENT PROJECT took place between November 20th and 30th, 2001 in Nepal. On behalf of the Studienkreis für Tourismus und Entwicklung e.V. (Institute for Tourism and Development) the data concerning the concept, aims and success of the project as stated in the contest documents could be verified without any problems – with the following results: The expert appraiser proposes that the TENGBOCHE DEVELOPMENT PROJECT be awarded the TO DO!-prize. 2. BACKGROUND 2.1 THE COUNTRY The Kingdom of Nepal is situated between the region of Tibet annexed by China in the North and India in the South. It stretches from east to west along the southern slopes of the Himalayas with a length of just under 900 km and a width of up to 250 km. With its area of 147 181 square kilometres – corresponding to the surface of Austria and Switzerland together – it has a population of just under 25 million people (census of July 2001).1 About 82 percent of Nepal’s population make their living out of farming. The per capita income per year is around 220 US dollars. With this, Nepal ranks among the poorest and least developed countries in the world with almost half of its population living below the poverty line. -

Everest Base Camp Trek 12 D/11 N

Everest Base Camp Trek 12 D/11 N Pre Trek: Travel to Kathmandu (1,300m): To ensure all permit paperwork and other necessary arrangements are completed before you trip it is important that you are in Kathmandu at least 24 hours prior to the trek commencement. The local operator will contact you to collect the required documents early in the afternoon. At 5:00 pm (17:00) a rickshaw will pick you up from your hotel and bring you to the trekking offices for a safety briefing on the nature of the trek, equipment and team composition. You will meet your trek leader and other team members. You can also make your last minute purchases of personal items as you will be flying to the Himalayas tomorrow. At 6:00 pm (18:00) we will make our way to a welcome dinner and cultural show where you will learn about Nepali culture, music and dance and get to know your trekking team. Overnight in Kathmandu (self selected) Included meals: Dinner DAY 01: Kathmandu to Lukla then trek to Phakding (2,652m): 25 minute flight, plus 3 to 4 hour trek. After breakfast you will be escorted to the domestic terminal of Kathmandu airport for an early morning flight to Lukla (2,800m), the gateway destination where our trek begins. After an adventurous flight above the breathtaking Himalaya, we reach the Tenzing-Hillary Airport at Lukla. This is one of the most beautiful air routes in the world culminating in a dramatic landing on a hillside surrounded by high mountain peaks. -

Nepal Everest Base Camp Trek Trip Packet

Nepal Mt. Everest Base Camp Trek TRIP SUMMARY Mt. Everest base camp is a magical place. TRIP DETAILS It’s nestled deep in the Himalayan mountain range, 30 • Price: $2,999 USD miles up the Khumbu valley. Its elevation is over 17,000 feet. Compared to the surrounding peaks, Everest base • Duration: 15 days camp is dwarfed by nearly 12,000 ft. • March 22 - April 5, 2019 • March/April, 2020 One of the most formidable facts about Everest base camp is that it’s constructed on a moving, living glacier. • Difficulty: Moderate-Difficult As the glacier moves down the Khumbu valley, it creeks and moans, giving the adventurous something to brag about. It’s no wonder that it’s found on bucket lists around the globe—as it should be. It’s Volant’s mission to safely escort individuals to base camp and back, while at the same time checking off for their clients one of the most desired bucket list items seen around the world! www.Volant.Travel "1 INCLUSIONS & MAP INCLUSIONS EXCLUSIONS • Scheduled meals in Kathmandu • Items of a personal nature (personal gear, • Round trip airport transfers telephone calls, laundry, internet us, etc.) • Scheduled hotels in Kathmandu • Airfare to Kathmandu • Airfare from Kathmandu to Lukla • Staff/guide gratuities • All meals and overnight accommodations while • Nonscheduled meals in Kathmandu on the trek • Alcoholic beverages • Porters and pack animals • Nepal visa costs: $40 USD, 30 days • Sagarmatha Nat’l Park entrance fee • Trip cancellation insurance • TIMS Card • Evacuation costs, medical, and rescue insurance To begin your adventure in Nepal, you’ll be picked up at Tribhuvan International Airport in Kathmandu by a Volant Travel representative and transferred to your hotel, the Hotel Mulberry. -

Spring/Summer 2010 in This Issue

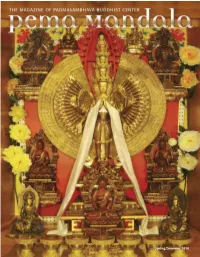

Spring/Summer 2010 In This Issue 1 Letter from the Venerable Khenpo Rinpoches 2 Brilliant Lotus Garland of Glorious Wisdom A Glimpse into the Ancient Lineage of Khenchen Palden Volume 9, Spring/Summer 2010 Sherab Rinpoche A Publication of 6 Entrusted: The Journey of Khenchen Rinpoche’s Begging Bowl Padmasambhava Buddhist Center 9 Fulfillment of Wishes: Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism Eight Great Stupas & Five Dhyani Buddhas Founding Directors 12 How I Met the Khenpo Rinpoches Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 14 Schedule of Teachings 16 The Activity Samayas of Anuyoga Ani Lorraine, Co-Editor An Excerpt from the 2009 Shedra, Year 7: Anuyoga Pema Dragpa, Co-Editor Amanda Lewis, Assistant Editor 18 Garland of Views Pema Tsultrim, Coordinator Beth Gongde, Copy Editor 24 The Fruits of Service Michael Ray Nott, Art Director 26 2009 Year in Review Sandy Mueller, Production Editor PBC and Pema Mandala Office For subscriptions or contributions to the magazine, please contact: Padma Samye Ling Attn: Pema Mandala 618 Buddha Highway Sidney Center, NY 13839 (607) 865-8068 [email protected] Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately for Cover: 1,000 Armed Chenrezig statue with the publication in a magazine representing the Five Dhyani Buddhas in the Shantarakshita Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Library at Padma Samye Ling Please email submissions to Photographed by Amanda Lewis [email protected]. © Copyright 2010 by Padmasambhava Buddhist Center International. Material in this publication is copyrighted and may not be reproduced by photocopy or any other means without obtaining written permission from the publisher.