Docent Handbook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northwest Fine Art & Antique Auction

Northwest Fine Art & Antique Auction August 27th, 2009 - 717 S 3rd St, Renton 14% Buyers Premium in Effect Auction Pick-up: Half Hour Following Auction or Friday, 08/28 & Tuesday, 09/01: Noon-5PM Lot Description 21 2 Boxes Loose Richard Lachman Cut Ink Drawings 1 Richard Kirsten "House of Many 22 3ea Richard Lachman Colored Ink Drawings Memories" Acrylic 22x16" 23 Box Richard Lachman Square Ink Drawings 2 Edna Crews "Snowcapped Forest" 24 4ea Richard Lachman Portrait Ink Drawings Watercolor 16x20.75" 25 Richard Lachman Large Sketchbook & 3 James Farr "Infinite Cycle of Renewal" Loose Ink Drawings 1973 Tempera 23.5x18.5" 26 Stack Richard Lachman Ink Drawings - 4 1997 S/N Abstract Etching Sketchbook Pages 5 Norman Lundin "Russian Landscape: 27 5x11' Oriental Rug Morning River" Charcoal/Pastel 26x37" 28 2 Carol Stabile Pastel Framed Paintings 6 K.C. McLaughlin "Exterior with 29 1969 Surrealist Mixed Media Painting Awnings" Dry Pigment 17x25" 34x30" - Signed Riote? 7 Edna Crews "Moonlit Meadow" 30 Signed F.W. Die? "Eye" Ink/Canvas 16x20" Watercolor 16.5x21.5" 31 Fred Marshall A.W.S. "Harbor - Puget 8 Edna Crews "Winter Meadow" Acrylic Sound" 1970 Watercolor 17x20.5" 31.5x23" 32 Fred Marshall Framed Watercolor 9 Richard Lachman "Cocktail Party" 1980 "Landscape with Deer" 16x21" Ink/Paper 16x22" 33 Flora Correa "Weeds Blowing" 1977 Collage 10 Richard Lachman "Dixy & Jaques" 24x12" Mixed Media 18x26" 34 Bonnie Anderson "Bucket of Lemons" Oil 11 Richard Lachman "Day Before Eden" 8x10" Mixed Media 18x26" 35 Bonnie Anderson "Lemon Drop Tree" Oil 12 Natalie McHenry Untitled – 38x14.25" "Marionettes" Watercolor 19x25" 36 Ray Hill Untitled - "Lake Scene" 1969 13 Edna Crews Untitled - "Mystic Bird" Watercolor 14x20" Oil/Board 40x30" 37 Signed S. -

Northwest Modernism & Western Fine Art Thursday June 20Th @ 5:00PM

Northwest Modernism & Western Fine Art Thursday June 20th @ 5:00PM 20% Buyers Premium In-House 25% Buyers Premium Online/Phone (425) 235-6345 SILENT AUCTIONS custom made Northwest Designer Craftsmen tansu chest with four drawers and door with Featuring a Large Silent Auction of metal pulls. Burned in mark on interior of Northwest Art & Native Books! drawer. Some scattered light surface wear. 5 Eames for Herman Miller Rosewood Lounge Lots 1,000’s End @ 8:00PM Chair & Ottoman. A vintage 670 & 671 set with black leather cushions. One of a pair Lot Description being offered. Chair 32''x33.5''x32'' and ottoman 17''x26''x22''. Original labels on 1 George Nakashima Studio Lounge Chair bottom dated Nov. 1 1978. Scattered wear to Rocker with Free Arm 32.5"x31"x34". A leather from use and one leather button is custom walnut rocking lounge chair with missing on chair seat. Overall excellent right free edge arm. Hickory wood spindles. condition. Charles and Ray Eames. Burned in mark on bottom with family name 6 Eames for Herman Miller "Time-Life" Stool on tape. Break to one spindle with scattered 15"x13". A vintage walnut stool or bench. light surface wear. Some light surface wear to top. Overall 2 Nakashima Style Free Edge Walnut Coffee excellent condition. Unmarked. Charles and Table 17.5"x79.5"x35". A long free edge Ray Eames. coffee table with trestle base. Unsigned. 7 Eames for Herman Miller Rosewood Lounge Some scattered light surface wear. From the Chair & Ottoman. A vintage 670 & 671 set same collection as the George Nakashima with black leather cushions. -

Annual Report for the Year 2003–2004

2003–2004 ANNUAL REPORT SAM Students with Sanislo Feast SAM CONNECTS ART TO LIFE CONTEMPORARY CHINESE ARTIST LI JIN’S A FEAST made a permanent impression on the fourth- and fifth-grade students at Sanislo Elementary School. Inspired by the fifty-nine- foot-long painting depicting food from a traditional Chinese dinner on a background of recipes written in Chinese calligraphy, the students set out to re-create their own version. Art teachers Ruth Winter and Carolyn Autenrieth designed the project to celebrate the diversity of cultures at their school. Students painted their favorite ethnic foods, and staff helped transcribe the recipes into the students’ original languages. On display at the Seattle Asian Art Museum last spring, the students’ work, Sanislo Feast, a fifty-foot-long art scroll portraying food and languages from seventeen different nations and cultures, reflected the heritage of Sanislo students and staff. Students, families and teachers commemorated the unveiling of their “masterpiece” with a special celebration at SAAM. cover: Li Jin, China, born 1958, A Feast, 2001, ink on Xuan paper, 39 3/8 x 708 5/8 in., Courtesy of the artist and CourtYard Gallery, Beijing right: Wolfgang Groschedel and Kunz Lochner, Equestrian armor for Philip II, ca. 1554, etched steel and gold, Patrimonio Nacional, Real Armería, Madrid SEATTLE ART MUSEUM TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Director’s Letter 17 Betty Bowen Award 2 Board of Trustees 18 Reaching Out to Youth & Families 3 Broadening, Deepening, Diversifying 19 Teaching and Learning 4–5 One Museum, Three -

View Brochure (PDF)

A NORTHWEST SUMMER MAY 4–OCTOBER 15, 2006 6 EXHIBITIONS * 1 CELEBRATION A NORTHWEST SUMMER Public Opening Celebration Saturday, May 6, 10 a.m.–5 p.m. The Northwest offers a great way of life and remarkable history that deserves to be appreciated in a big way. Our special exhibit, A Northwest Summer, will do just that. To kick off the tribute, we’re hosting a fusion of art activities and entertainment that contribute to making this region special. Come join the celebration—enjoy an art activity, watch an Asian art demonstration, listen to live music and shop the eclectic, uniquely Northwest crafts of “I Heart Rummage.” For more information, check out seattleartmuseum.org. Director’s Welcome As we look forward—to the opening of above: Trimpin, U.S.A., born Germany 1951, drawing for Picnics, Rhythms and Vacations installation, 2006; cover: Trimpin, The Orange Piano, Lake Union, the Olympic Sculpture Park this fall and Seattle, 2003. Photo: Theo Bernardi. In this work, a hydrophone records underwater sound pollution, creating an audio signal, which becomes information played automatically by the piano. to the re-opening of the expanded downtown museum next spring—we have naturally looked back, reflecting on the amazing seventy-five years of growth that Trimpin: Picnics, Rhythms and Vacations the Seattle Art Museum has experienced. August 8–October 15, 2006 Milestones of that history are noted in the timeline, putting the past in context for Picnics, Rhythms and Vacations, 2006, a new installation by musician, sculptor and composer Trimpin, the celebrations in Volunteer Park this will be presented at the Seattle Asian Art Museum. -

Encyklopédia Kresťanského Umenia

Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia americká architektúra - pozri chicagská škola, prériová škola, organická architektúra, Queen Anne style v Spojených štátoch, Usonia americká ilustrácia - pozri zlatý vek americkej ilustrácie americká retuš - retuš americká americká ruleta/americké zrnidlo - oceľové ozubené koliesko na zahnutej ose, užívané na zazrnenie plochy kovového štočku; plocha spracovaná do čiarok, pravidelných aj nepravidelných zŕn nedosahuje kvality plochy spracovanej kolískou americká scéna - american scene americké architektky - pozri americkí architekti http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_architects americké sklo - secesné výrobky z krištáľového skla od Luisa Comforta Tiffaniho, ktoré silno ovplyvnili európsku sklársku produkciu; vyznačujú sa jemnou farebnou škálou a novými tvarmi americké litografky - pozri americkí litografi http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:American_women_printmakers A Anne Appleby Dotty Atti Alicia Austin B Peggy Bacon Belle Baranceanu Santa Barraza Jennifer Bartlett Virginia Berresford Camille Billops Isabel Bishop Lee Bontec Kate Borcherding Hilary Brace C Allie máj "AM" Carpenter Mary Cassatt Vija Celminš Irene Chan Amelia R. Coats Susan Crile D Janet Doubí Erickson Dale DeArmond Margaret Dobson E Ronnie Elliott Maria Epes F Frances Foy Juliette mája Fraser Edith Frohock G Wanda Gag Esther Gentle Heslo AMERICKÁ - AMES Strana 1 z 152 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia Charlotte Gilbertson Anne Goldthwaite Blanche Grambs H Ellen Day -

The Weyerhauser Art Collection + MORE!

The Weyerhauser Art Collection + MORE! December 11th @ 5PM - EARLY START! 16% Buyers Premium In-House 19% Online & Phone Bidding Online Bidding Through LiveAuctioneers 717 S Third St Renton, WA (425) 235-6345 SILENT AUCTION ITEMS 6 4pc Antique Chinese Pheasant Silk Rank Lot 1,000's END @ 8:00PM Badges 10.5"x11" and 11"x12" Sets. Two Mandarin square front chest plate and back Lot Description patch sets. Polychrome silk embroidery. Staining and some edge fray. Qing dynasty. 1 Antique Chinese Silk Embroidered Dragon 7 7pc Antique Chinese Silk Embroidery. Robe 40"x52". Depicts four panels of Includes a large forbidden stitch panel forward facing five-clawed dragons in gold 27"x14", a pair of blue and white forbidden thread. Forbidden stitch sleeves with stitch lotus panels 8"x9.5" each, a round blossoming lotus flowers. Some staining. shou symbol panel 8.5" diameter, a pheasant Late Qing dynasty. Mandarin square rank badge 8"x8", and a 2 3pc Antique Chinese Pheasant Rank Badges gold thread leopard Mandarin square rank 11"x12" Each Approx. Each Mandarin chest badge 11"x12". There is also half a square has gold thread with silk chest plate rank badge. All have edge fray embroidered blossoming flowers. Also a and some soiling. Qing dynasty. coral colored beaded moon at the top corner. 8 Antique Chinese Imperial Dragon Kesi Silk Scattered fray and some staining. Qing Round Rank Badge 11" Diameter. Depicts a dynasty. gold thread five-clawed dragon with 3 4pc Antique Chinese Pheasant Rank Badges flaming pearl. Light soiling. Qing dynasty. 11"x12" Each Approx. -

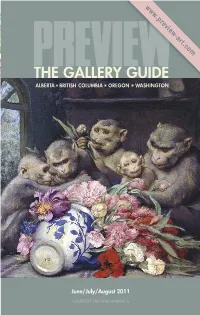

Preview – the Gallery Guide | June Through August 2011

w w w .p re vi ew -a r t. co m THE GALLERY GUIDE ALBERT A I BRITISH COLUMBI A I OREGO N I WASHINGTON June/July/August 2011 COURTESY PREVIEW GRAPHICS “ S T U D I O E LESLIE V E N T / A R T I F POOLE A C T S ” , a c r y l i c R a n E d i P n k R o G n E c A a S n v R a E s , Y N 6 0 x T M 7 A 2 A i n T c h I I e E V s ( R 5 E p a F n 6 e O l s 0 ) R 4 - L 5 E 2 S 5 L - I 4 E 0 P 2 O 5 O L E Also represented by: EDMONTON : Scott Gallery CALGARY : Vir ginia Christ opher Fine Art VICTORIA : Winchester Galleries PALM DESERT : Gallery Soho 8 PREVIEW I JUNE/JULY/AUGUST 2011 June/July/ August 2011 previews Vol. 25 No.3 ALBERTA 12 Gabriel von Max 10 Black Diamond, Calgary Frye Art Museum 17 Edmonton 14 TRAFFIC: Conceptual Art in Canada 1965-1980 20 Lethbridge, Medicine Hat Art Gallery of Alberta BRITISH COLUMBIA 74 21 Abbotsford, Bowen Island, 20 The Solitudes of Place: Ann Kipling Burnaby Burnaby Art Gallery 25 Campbell River, Castlegar, 24 Gabor Szilasi: The Eloquence of the Everyday Chemainus, Chilliwack Kelowna Art Gallery 27 Coquitlam, Courtenay, 28 Fibred Optics Cumberland, Fort Langley 28 Gibsons, Grand Forks, Richmond Art Gallery Kamloops 30 30 Karlheinz Weinberger: Intimate Stranger 29 Kaslo, Kelowna Presentation House Gallery 30 Maple Ridge, Nanaimo, Nelson 36 Mise-en-Scène 32 New Westminster, North Vancouver 34 Osoyoos, Penticton Elizabeth Leach Gallery 52 35 Port Moody, Prince George, 40 Material Bloom/Barbara Cohen & Peter Pierobon Prince Rupert Circle Craft Gallery 36 Qualicum Beach, Richmond 52 Robert Kleyn 37 Salmon Arm, Salt Spring -

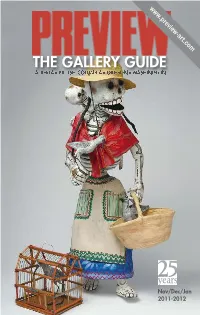

Preview – the Gallery Guide | November 2011

w w w .p re vi ew -a rt .c om THE GALLERY GUIDE ALBERTA I BRITISH COLUMBIA I OREGON I WASHINGTON Nov/Dec/Jan 2011-2012 Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas SOLO TWO November 5 – 26, 2011 1 1 0 2 , s e h c n i 0 4 X 6 2 , r e p a p n o a i d e m d e x i m , 6 2 . 5 . 1 1 0 2 r e g g i B , s a a n a l u g h a Y l l o c i N l e a h c i M Opening reception: November 5, 2-4pm DOUGLAS UDELL GALLERY 1566 West 6 th Ave Vancouver, BC V6J 1R2 www.douglasudellgallery.com • 604-736-8900 Serving the visual arts community since 1986 Celebrating 25 years www.preview-art.com 8 PREVIEW I NOVEMBER/DECEMBER/JANUARY 2011/12 Nov/Dec/Jan 2011/2012 previews Vol. 25 No.5 12 Lesley Dill’s Poetic Visions ALBERTA Whatcom Museum 10 Black Diamond, Calgary 20 Edmonton 14 Douglas Coupland: Twelve Slogans 21 Lethbridge 8 TrépanierBaer Gallery 38 2 22 Medicine Hat 16 Norman Lundin: Inside/Outside BRITISH COLUMBIA Hallie Ford Museum of Art 23 Abbotsford, Burnaby 18 Group Exhibition/Emotional Blackmail 24 Campbell River, Castlegar, Southern Alberta Art Gallery 25 Chemainus, Chilliwack, 22 Painting Seattle: Tokita & Nomura Coquitlam Seattle Asian Art Museum 27 Courtenay, Fort Langley, Gibsons, Grand Forks 28 24 Robert Orchardson: Endless façade 30 Kamloops , Kaslo Contemporary Art Gallery 31 Kelowna, Maple Ridge 30 Nature, Knowledge and the Knower 32 Nanaimo, Nelson, Satellite Gallery New Westminster , North Vancou ver 36 Kate Scoones: Wish You Were Here 34 Osoyoos, Penticton, Port Moody, Polychrome Fine Arts Prince George, Prince Rupert 38 Ray Mead (1921-1998) 35 Qualicum Beach, -

Voyager: STEVE JENSEN

TM Voyager: STEVE JENSEN Also on exhibit: The 2017 Pilchuck Glass School Emerging Artists in Residence OCTOBER 4 – NOVEMBER 3, 2018 Volume 27 September • October 2018 Number 5 www.ArtAccess.com 2 ArtAccess.com © September • October 2018 ArtAccess.com © September • October 2018 3 THE MONTHLY GUIDE TO THE ARTS ART ACCESS CONTENTS Volume 27 Number 5 “Writing is a lonely business.” FEATURE ~ Sherman Alexie Feature “In Red Ink” at the Museum of Northwest Art American Writer …Susan Noyes Platt 8 VISUAL ART Anacortes, WA 10 Bainbridge Island, WA 10 Bellevue, WA 12 Bellingham, WA 13 Camano Island, WA 14 Listings Edison, WA 14 Edmonds, WA 15 Ellensburg, WA 16 Everett, WA 16 Steve Jensen • “Crystal Swirling Boat” cast lead crystal, 9 x 24 x 9, photo credit: Linda Young Friday Harbor, WA 16 Schack Art Center • Everett, WA Gig Harbor, WA 17 Kingston, WA 17 Front Cover: Steve Jensen • “Fish Eye Canoe” Kirkland, WA 17 photo credit: Linda Young Schack Art Center • Everett, WA La Conner, WA 18 Mercer Island, WA 18 Port Angeles, WA 19 VOYAGER: Steve Jensen Port Orchard, WA 19 October 4 – November 3, 2018 Port Townsend, WA 19 Reception: Thursday, October 4, 5-8 P.M. Poulsbo, WA 20 Seattle, WA 2017 Pilchuck Glass School • Ballard 21 Emerging Artists in Residence • Columbia City 21 Collin Bampton, Lydia Boss, Courtney • Downtown 21 Dodd, Morgan Gilbreath, María Renée • First Hill 23 Morales Lam, and Bryan McGovern Wilson • Mount Baker 23 October 4 – November 3, 2018 • Pioneer Square 24 Reception: Thursday, October 4, 5-8 P.M. • University District 28 Exhibits sponsored by • Wallingford 29 • West Seattle 29 Tacoma, WA 29 Whidbey Island, WA 29 Schack Art Center Yakima, WA 30 2921 Hoyt Avenue • Everett, WA (425) 259-5050 • [email protected] CALL TO ARTISTS 30 Mon-Fri: 10A.M.-6 P.M., MAPS Sat: 10 A.M.-5 P.M., Sun: 12-5 P.M. -

Permanent Collection Artwork

Berenice Abbott Berenice Abbott Gunsmith and Police Departmment, 6 Center Market Place, Manhatt Oldest Apartment House in New York City, 142 East 18th Street Man gelatin silver print 1937 gelatin silver print 1935 Donated By Harry Blumenthal and Scott Mitchell Donated By Harry Blumenthal and Scott Mitchell Berenice Abbott Fermin Aguayo Repair Shop, Christopher St. New York City A Walk in The Mountains gelatin silver print printed 1969 Oil on Canvas 1957 Donated By Harry Blumenthal and Scott Mitchell Donated By Morris Graves and Robert Yarber Page 1 of 109 Fermin Aguayo Fermin Aguayo Beautiful Painting of Violet Sweet Pure Air Oil on Canvas 1956 Oil on Canvas 1957 Donated By Morris Graves and Robert Yarber Donated By Morris Graves and Robert Yarber Guy Anderson Guy Anderson Christmas Card (The Stillness of the Seed Falling) Untitled Woodblock and Script 1964 mixed media; oil on plywood and rusted metal Undated Donated By David and Sharon Cammarano Collection Donated By David and Sharon Cammarano Collection Page 2 of 109 William Anderson William Anderson Beyond the 95th Meridian Geronimo and Family Silkscreen on Plexiglass 1980 Silkscreen Donated By unknown Donated By John and Lyn Pauley William Anderson Laura Adams Armer Ship The Forest Pool Mixed Media Book 1963 Donated By John and Lyn Pauley Donated By Helen Everett Page 3 of 109 Laura Adams Armer Laura Adams Armer Untitled (#1 from The Forest Pool) Untitled (#3 from The Forest Pool) Tempera 1938 Color Print (Not Original) 1938 Donated By Helen Everett Donated By Helen Everett Laura Adams -

The Gallery Guide | April-May 2011

w w w .p re vi ew -a rt .c om THE GALLERY GUIDE ALBERT A I BRITISH COLUMBI A I OREGO N I WASHINGTON April/May 2011 COURTESY PREVIEW GRAPHICS 4 PREVIEW I APRIL/MAY 2011 # OPEN LATE ON FIRST THURSDAYS 6 PREVIEW I APRIL/MAY 2011 Apr/May 2011 48 Vol. 25 No.2 previews ALBERTA 10 Jay Senetchko 8 Black Diamond, Calgary Ian Tan Gallery 14 Edmonton Pera Art Gallery 16 Lethbridge 12 Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait 17 Medicine Hat Glenbow Museum BRITISH COLUMBIA 17 Abbotsford, Burnaby 70 16 The Art of Norman Rockwell 20 Campbell River Tacoma Art Museum 22 Castlegar, Chemainus, Chilliwack, 20 Arnold Shives Coquitlam Burnaby Art Gallery 23 Courtenay, Fort Langley, Gibsons, Grand Forks 30 Brian Jungen 25 Kamloops , Kaslo, Kelowna, Art Gallery of Alberta Nelson, New Westminster , 46 Heather Passmore: Form Letters North Vancou ver The New Gallery 26 Maple Ridge, Nanaimo 48 Glory of Kings: Ethiopian Christian Art 28 Osoyoos, Penticton, Port Moody, Hallie Ford Museum of Art Prince George, Prince Rupert 18 29 Qualicum Beach, Richmond, 50 Kristin Bjornerud: New Paintings Salmon Arm, Salt Spring Island Gallery Jones 30 Sidney , Sooke , Squamish 52 Sharon Hayes: In the Near Future 31 Sunshine Coast, Surrey Contemporary Art Gallery 34 Tsawwassen, Vancouver 9 60 Jamasie Pitseolak 54 Vernon, Victoria 59 West Vancouver Marion Scott Gallery 60 Whistler, White Rock 66 Laurie Herrick OREGON Museum of Contemporary Craft 61 Cannon Beach, Marylhurst, 70 Carl Beam Portland Museum of Anthropology 62 Salem 63 72 Nick Cave WASHINGTON Seattle Art Museum 62 Bellevue, Bellingham 64 Ellensburg, Friday Harbor, La Conner, Longview, Port Angeles vignettes 65 Seattle 30 70 Spokane, Tacoma 9 Alberta © 1986-2011 Preview Graphics Inc. -

Northwest & Western Fine Art + Objects!

Northwest & Western Fine Art + Objects! Thursday September 19th @ 5:00PM 20% Buyers Premium In-House 25% Buyers Premium Online/Phone (425) 235-6345 SILENT AUCTIONS one 23 5/8" leaf. Also a set of four model 122 dining chairs 31.25"x19"x18" each. Burned Featuring a Silent Auction of in marks on bottom. Some scattered wear Northwest & Western Artwork! from age. Denmark mid century modern. 5 Hans Olsen Danish Teak Sideboard Lots 1,000’s End @ 8:00PM 31.5"x72"x17". Mid century four drawer buffet with two sliding doors and adjustable Lot Description shelves. Burnt in mark on bottom, Made in Denmark. Some slight surface wear from 1 Eames for Herman Miller Rosewood Lounge age. Overall excellent condition. Chair & Ottoman. A vintage 670 & 671 set 6 7pc Niels Moller for J.L. Mollers Danish with brown leather cushions. Chair Teak Dining Set. Includes a set of six model 31''x32''x35'' and ottoman 16''x26''x21''. 71 and 55 teak dining chairs with danish cord Original labels on bottom dated June 1, 1976. seats 31"x19.5"x19" and 31"x24"x19". Teak Brown leather has been professionally dining table measures 29"x71"x41" and 117" restored. Some minor edge wear to rosewood when hidden leaves are out. Marks on shells. Overall excellent condition. Charles bottom. Some scattered surface wear from and Ray Eames. use. Overall excellent condition. Mid century 2 Torbjorn Afdal for Bruksbo "Krobo" Teak modern. Bench or Coffee Table 13"x59"x14.5". Made 6A Frank Lloyd Wright "Usonian" Oak in Norway. Original labels on bottom.