Exploring Partnership Opportunities to Achieve Universal Health Access 2016 Uganda Private Sector Assessment in Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elite Strategies and Contested Dominance in Kampala

ESID Working Paper No. 146 Carrot, stick and statute: Elite strategies and contested dominance in Kampala Nansozi K. Muwanga1, Paul I. Mukwaya2 and Tom Goodfellow3 June 2020 1 Department of Political Science and Public Administration, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. Email correspondence: [email protected] 2 Department of Geography, Geo-informatics and Climatic Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda. Email correspondence: [email protected]. 3 Department of Urban Studies and Planning, University of Sheffield, UK Email correspondence: [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-912593-56-9 email: [email protected] Effective States and Inclusive Development Research Centre (ESID) Global Development Institute, School of Environment, Education and Development, The University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, UK www.effective-states.org Carrot, stick and statute: Elite strategies and contested dominance in Kampala. Abstract Although Yoweri Museveni’s National Resistance Movement (NRM) has dominated Uganda’s political scene for over three decades, the capital Kampala refuses to submit to the NRM’s grip. As opposition activism in the city has become increasingly explosive, the ruling elite has developed a widening range of strategies to try and win urban support and constrain opposition. In this paper, we subject the NRM’s strategies over the decade 2010-2020 to close scrutiny. We explore elite strategies pursued both from the ‘top down’, through legal and administrative manoeuvres and a ramping up of violent coercion, and from the ‘bottom up’, through attempts to build support among urban youth and infiltrate organisations in the urban informal transport sector. Although this evolving suite of strategies and tactics has met with some success in specific places and times, opposition has constantly resurfaced. -

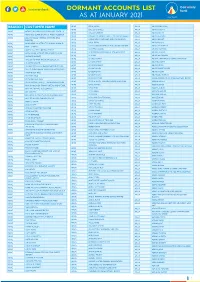

1612517024List of Dormant Accounts.Pdf

DORMANT ACCOUNTS LIST AS AT JANUARY 2021 BRANCH CUSTOMER NAME APAC OKAE JASPER ARUA ABIRIGA ABUNASA APAC OKELLO CHARLES ARUA ABIRIGA AGATA APAC ACHOLI INN BMU CO.OPERATIVE SOCIETY APAC OKELLO ERIAKIM ARUA ABIRIGA JOHN APAC ADONGO EUNICE KAY ITF ACEN REBECCA . APAC OKELLO PATRICK IN TRUST FOR OGORO ISAIAH . ARUA ABIRU BEATRICE APAC ADUKU ROAD VEHICLE OWNERS AND OKIBA NELSON GEORGE AND OMODI JAMES . ABIRU KNIGHT DRIVERS APAC ARUA OKOL DENIS ABIYO BOSCO APAC AKAKI BENSON INTRUST FOR AKAKI RONALD . APAC ARUA OKONO DAUDI INTRUST FOR OKONO LAKANA . ABRAHAM WAFULA APAC AKELLO ANNA APAC ARUA OKWERA LAKANA ABUDALLA MUSA APAC AKETO YOUTH IN DEVELOPMENT APAC ARUA OLELPEK PRIMARY SCHOOL PTA ACCOUNT ABUKO ONGUA APAC AKOL SARAH IN TRUST FOR AYANG PIUS JOB . APAC ARUA OLIK RAY ABUKUAM IBRAHIM APAC AKONGO HARRIET APAC ARUA OLOBO TONNY ABUMA STEPHEN ITO ASIBAZU PATIENCE . APAC AKULLU KEVIN IN TRUST OF OLAL SILAS . APAC ARUA OMARA CHRIST ABUME JOSEPH APAC ALABA ROZOLINE APAC ARUA OMARA RONALD ABURA ISMAIL APAC ALFRED OMARA I.T.F GERALD EBONG OMARA . APAC ARUA OMING LAMEX ABURE CHRISTOPHER APAC ALUPO CHRISTINE IN TRUST FOR ELOYU JOVIN . APAC ARUA ONGOM JIMMY ABURE YASSIN APAC AMONG BEATRICE APAC ARUA ONGOM SILVIA ABUTALIBU AYIMANI APAC ANAM PATRICK APAC ARUA ONONO SIMON ACABE WANDI POULTRY DEVELPMENT GROUP APAC ANYANGO BEATRASE APAC ARUA ONOTE IRWOT VILLAGE SAVINGS AND LOAN ACEMA ASSAFU APAC ANYANZO MICHEAL ITF TIZA BRENDA EVELYN . APAC ARUA OPIO JASPHER ACEMA DAVID APAC APAC BODABODA TRANSPORTERS AND SPECIAL APAC ARUA OPIO MARY ACEMA ZUBEIR APAC APALIKA FARMERS ASSOCIATION APAC ARUA OPIO RIGAN ACHEMA ALAHAI APAC APILI JUDITH APAC ARUA OPIO SAM ACHIDRI RASULU APAC APIO BENA IN TRUST OF ODUR JONAN AKOC . -

Uganda Date: 30 October 2008

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: UGA33919 Country: Uganda Date: 30 October 2008 Keywords: Uganda – Uganda People’s Defence Force – Intelligence agencies – Chieftaincy Military Intelligence (CMI) – Politicians This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. Please provide any information on the following people: 2. Noble Mayombo (Director of Intelligence). 3. Leo Kyanda (Deputy Director of CMI). 4. General Mugisha Muntu. 5. Jack Sabit. 6. Ben Wacha. 7. Dr Okungu (People’s Redemption Army). 8. Mr Samson Monday. 9. Mr Kyakabale. 10. Deleted. RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. The Uganda Peoples Defence Force UPDF is headed by General Y Museveni and the Commander of the Defence Force is General Aronda Nyakairima; the Deputy Chief of the Defence Forces is Lt General Ivan Koreta and the Joint Chief of staff Brigadier Robert Rusoke. -

Uganda 2020 Human Rights Report

UGANDA 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Uganda is a constitutional republic led since 1986 by President Yoweri Museveni of the National Resistance Movement party. In 2016 voters re-elected Museveni to a fifth five-year term and returned a National Resistance Movement majority to the unicameral parliament. Allegations of disenfranchisement and voter intimidation, harassment of the opposition, closure of social media websites, and lack of transparency and independence in the Electoral Commission marred the elections, which fell short of international standards. The periods before, during, and after the elections were marked by a closing of political space, intimidation of journalists, and widespread use of torture by the security agencies. The national police maintain internal security, and the Ministry of Internal Affairs oversees the police. While the army is responsible for external security, the president detailed army officials to leadership roles within the police force. The Ministry of Defense oversees the army. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. Members of the security forces committed numerous abuses. Significant human rights issues included: unlawful or arbitrary killings by government forces, including extrajudicial killings; forced disappearance; torture and cases of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment by government agencies; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; arbitrary arrest or detention; political prisoners or detainees; serious problems with the -

THE UGANDA GAZETTE [13Th J Anuary

The THE RH Ptrat.ir OK I'<1 AND A T IE RKPt'BI.IC OF UGANDA Registered at the Published General Post Office for transmission within by East Africa as a Newspaper Uganda Gazette A uthority Vol. CX No. 2 13th January, 2017 Price: Shs. 5,000 CONTEXTS P a g e General Notice No. 12 of 2017. The Marriage Act—Notice ... ... ... 9 THE ADVOCATES ACT, CAP. 267. The Advocates Act—Notices ... ... ... 9 The Companies Act—Notices................. ... 9-10 NOTICE OF APPLICATION FOR A CERTIFICATE The Electricity Act— Notices ... ... ... 10-11 OF ELIGIBILITY. The Trademarks Act—Registration of Applications 11-18 Advertisements ... ... ... ... 18-27 I t is h e r e b y n o t if ie d that an application has been presented to the Law Council by Okiring Mark who is SUPPLEMENTS Statutory Instruments stated to be a holder of a Bachelor of Laws Degree from Uganda Christian University, Mukono, having been No. 1—The Trade (Licensing) (Grading of Business Areas) Instrument, 2017. awarded on the 4th day of July, 2014 and a Diploma in No. 2—The Trade (Licensing) (Amendment of Schedule) Legal Practice awarded by the Law Development Centre Instrument, 2017. on the 29th day of April, 2016, for the issuance of a B ill Certificate of Eligibility for entry of his name on the Roll of Advocates for Uganda. No. 1—The Anti - Terrorism (Amendment) Bill, 2017. Kampala, MARGARET APINY, 11th January, 2017. Secretary, Law Council. General N otice No. 10 of 2017. THE MARRIAGE ACT [Cap. 251 Revised Edition, 2000] General Notice No. -

The Uganda Gazette, General Notice No. 425 of 2021

LOCAL GOVERNMENT COUNCIL ELECTIONS, 2021 SCHEDULE OF ELECTION RESULTS FOR DISTRICT/CITY DIRECTLY ELECTED COUNCILLORS DISTRICT CONSTITUENCY ELECTORAL AREA SURNAME OTHER NAME PARTY VOTES STATUS ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ABIM KIYINGI OBIA BENARD INDEPENDENT 693 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ABIM OMWONY ISAAC INNOCENT NRM 662 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ABIM TOWN COUNCIL OKELLO GODFREY NRM 1,093 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ABIM TOWN COUNCIL OWINY GORDON OBIN FDC 328 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ABUK TOWN COUNCIL OGWANG JOHN MIKE INDEPENDENT 31 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ABUK TOWN COUNCIL OKAWA KAKAS MOSES INDEPENDENT 14 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ABUK TOWN COUNCIL OTOKE EMMANUEL GEORGE NRM 338 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ALEREK OKECH GODFREY NRM Unopposed ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ALEREK TOWN COUNCIL OWINY PAUL ARTHUR NRM Unopposed ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ATUNGA ABALLA BENARD NRM 564 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY ATUNGA OKECH RICHARD INDEPENDENT 994 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY AWACH ODYEK SIMON PETER INDEPENDENT 458 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY AWACH OKELLO JOHN BOSCO NRM 1,237 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY CAMKOK ALOYO BEATRICE GLADIES NRM 163 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY CAMKOK OBANGAKENE POPE PAUL INDEPENDENT 15 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY KIRU TOWN COUNCIL ABURA CHARLES PHILIPS NRM 823 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY KIRU TOWN COUNCIL OCHIENG JOSEPH ANYING UPC 404 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY LOTUKEI OBUA TOM INDEPENDENT 146 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY LOTUKEI OGWANG GODWIN NRM 182 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY LOTUKEI OKELLO BISMARCK INNOCENT INDEPENDENT 356 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY MAGAMAGA OTHII CHARLES GORDON NRM Unopposed ABIM LABWOR COUNTY MORULEM OKELLO GEORGE ROBERT NRM 755 ABIM LABWOR COUNTY MORULEM OKELLO MUKASA -

Militarization in East Africa 2017

Adams Annotated Bibliography on Militarization in East African 1 SSHRC Partnership: Conjugal Slavery in Wartime Masculinities and Femininities Thematic Group Annotated Bibliography on Militarization of East Africa Aislinn Adams, Research Assistant Adams Annotated Bibliography on Militarization in East African 2 Table of Contents Statistics and Military Expenditure ...................................................................................... 7 World Bank. “Military Expenditure (% of GDP).” 1988-2015. ..................................................... 7 Military Budget. “Military Budget in Uganda.” 2001-2012. ........................................................... 7 World Bank. “Expenditure on education as % of total government expenditure (%).” 1999-2012. ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 World Bank. “Health expenditure, public (% of GDP).” 1995-2014. ............................................. 7 World Health Organization. “Uganda.” ......................................................................................... 7 - Total expenditure on health as % if GDP (2014): 7.2% ......................................................... 7 United Nations Development Programme. “Expenditure on health, total (% of GDP).” 2000- 2011. ................................................................................................................................................ 7 UN Data. “Country Profile: Uganda.” -

Makerere-University-62Nd-Graduation-List.Pdf

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY THE 62nd CONGREGATION OF THE UNIVERSITY FOR THE CONFERMENT OF DEGREES AND Award of DIPLOMAS TO BE HELD AT THE FREEDOM SQUARE from Monday 16th January to Friday 20th January 2012 starting at 9.00am nd Monday, January 16, 2012 62 CONGREGATION The Principal, College of Conferment of the Degree of weevils which are the major Agricultural and Environmental Doctor of Philosophy (Agriculture- sweetpotato pests in Africa. Through Sciences to present the following Crop Science) extensive field and laboratory for the studies, she demonstrated the effect Conferment of the Degree of MBANZIBWA Deusdedith Rugaiukamu of these compounds on Cylas weevil Doctor of Philosophy (Agriculture) Mr. Mbanzibwa’s research focused on biology. Her pioneering research assessment of the “genetic variability links for the first time sweetpotato BEYENE Dereje Degefie and population structure of Cassava root chemical composition and brown streak disease (CBSD) resistance. This research funded Mr. Beyene’s research focused on associated viruses in East Africa”. by the McKnight Foundation in “characterization and expression CBSD continues to be a serious collaboration with NARO, has analysis of Isoamylase1 (Meisa1) starch cause of cassava yield losses in East provided basis on which breeding gene in cassava and its wild relatives”. Africa. The causal agent of CBSD was for weevil resistant sweetpotato In this study a cDNA clone of a previously thought to be Cassava varieties is to be done. Manihot esculenta Isoamylase1 gene, brown streak virus (CBSV) alone. a member of starch-debranching This study has clearly demonstrated enzyme family in cassava storage Conferment of the Degree of that there are two distinct CBSD- Doctor of Philosophy (Agriculture) root was characterized. -

An Independent Review of the Performance of Special Interest Groups in Parliament

DEEPENING DEMOCRACY AND ENHANCING SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS IN UGANDA DEEPENING DEMOCRACY AND ENHANCING SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS IN UGANDA An Independent Review of the Performance of Special Interest Groups in Parliament Arthur Bainomugisha Elijah D. Mushemeza ACODE Policy Research Series, No. 13, 2006 i DEEPENING DEMOCRACY AND ENHANCING SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS IN UGANDA DEEPENING DEMOCRACY AND ENHANCING SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS IN UGANDA An Independent Review of the Performance of Special Interest Groups in Parliament Arthur Bainomugisha Elijah D. Mushemeza ACODE Policy Research Series, No. 13, 2006 ii DEEPENING DEMOCRACY AND ENHANCING SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS IN UGANDA TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS................................................................ iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................ iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.............................................................. v 1.0. INTRODUCTION............................................................. 1 2.0. BACKGROUND: CONSTITUTIONAL AND POLITICAL HISTORY OF UGANDA.......................................................... 2 3.0. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY................................................... 3 4.0. LEGISLATIVE REPRESENTATION AND ENVIRONMENTAL GOVERNANCE.................................................................... 3 5.0. UNDERSTANDING THE CONCEPTS OF AFFIRMATIVE ACTION AND REPRESENTATION.................................................. 5 5.1. Representative Democracy in a Historical Perspective............................................................. -

October 2019-April 2020

Overview of the Human Rights Situation in the East and Horn of Africa October 2019 – April 2020 Report submitted to the 66th Ordinary Session of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights Banjul, The Gambia April 2020 (postponed to a later date because of the COVID-19 situation) DEFENDDEFENDERS (THE EAST AND HORN OF AFRICA HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS PROJECT) Human Rights House Plot 1853, John Kiyingi Road, Nsambya, P.O. Box 70356 Kampala, Uganda +256 393 265 820 www.defenddefenders.org Contacts: Hassan Shire Sheikh (Executive Director) [email protected] +256 772 753 753 Estella Kabachwezi (Senior Advocacy and Research Officer) [email protected] +256 393 266 827 Nicolas Agostini (Representative to the United Nations) [email protected] +41 79 813 49 91 Table of Contents Introduction and Executive Summary .......................................................................................... 3 Recommendations .......................................................................................................................... 5 Burundi ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Djibouti ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Eritrea ............................................................................................................................................. 11 Ethiopia .......................................................................................................................................... -

Accountable Government in Africa Perspectives from Public Law and Political Studies

C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Accountable Government in Africa Perspectives from public law and political studies EDITORS DANWOOD M. CHIRWA LIA NIJZINK United Nations University Press TOKYO • NEW YORK • PARIS Accountable Government in Africa: Perspectives from public law and political studies First Published 2013 Print published in 2012 in South Africa by UCT Press An imprint of Juta and Company Ltd First Floor Sunclare Building 21 Dreyer Street Claremont, 7708 South Africa www.uctpress.co.za © 2012 UCT Press Published in 2012 in North America, Europe and Asia by United Nations University Press United Nations University, 53-70, Jingumae 5-chome, Shibuya-ku, Tokyo 150-8925, Japan Tel: +81-3-5467-1212 Fax: +81-3-3406-7345 E-mail: [email protected] General enquiries: [email protected] http://www.unu.edu United Nations University Office at the United Nations, New York 2 United Nations Plaza, Room DC2-2062, New York, NY 10017, USA Tel: +1-212-963-6387 Fax: +1-212-371-9454 E-mail: [email protected] United Nations University Press is the publishing division of the United Nations University. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publishers. ISBN 978-1-91989-537-6 (Parent) ISBN 978-1-92054-163-7 (WebPDF) ISBN 978-92-808-1205-3 (North America, Europe and South East Asia) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Accountable government in Africa : perspectives from public law and political studies / editors: Danwood M. Chirwa, Lia Nijzink. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Government Says There Have Been Sustained and Organised Efforts to Kill Some of the Rwandan Refugees Living in South Africa.&Qu

[Government says there have been sustained and organised efforts to kill some of the Rwandan refugees living in South Africa."It is clear that these incidents directly link to tensions emanating from Rwanda and are acted upon within our borders," said spokesperson for the Department of International Relations and Cooperation Clayson Monyela on Saturday.In June 2010, there was an attack on the life of General Kayumba Nyamwasa, an asylum seeker and former Rwanda Army General.] BURUNDI : Le Burundi suspend les activités d'un parti d'opposition par RFI /17-03-2014 Au Burundi, les condamnations et autres appels à la modération lancés par la communauté internationale n’y ont rien fait. Après les violents affrontements entre les militants d’un parti d’opposition et la police, qui a tiré contre les manifestants, l’heure semble être à la répression. Le gouvernement burundais vient de franchir, durant le week-end du 15 mars, un palier supplémentaire dans la voie de la répression. Le ministre burundais de l’Intérieur Edouard Nduwimana a en effet suspendu le Mouvement pour la solidarité et la sémocratie (MSD) d’activités pour quatre mois et ferme ses locaux sur toute l’étendue du pays. Ce parti d’opposition, encore sonné par les coups de boutoir qu’il vient de recevoir, a décidé de plier pour ne pas donner « un prétexte à des mesures encore plus contraignantes ». Et sur un ton sarcastique, François Nyamoya, porte-parole du MSD ajoute que « de toute façon, on était déjà suspendu de facto, car le pouvoir nous interdit systématiquement de manifester et même de tenir de simples réunions depuis des mois ».