The American Art-Union and the Rise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2018–2019 Artmuseum.Princeton.Edu

Image Credits Kristina Giasi 3, 13–15, 20, 23–26, 28, 31–38, 40, 45, 48–50, 77–81, 83–86, 88, 90–95, 97, 99 Emile Askey Cover, 1, 2, 5–8, 39, 41, 42, 44, 60, 62, 63, 65–67, 72 Lauren Larsen 11, 16, 22 Alan Huo 17 Ans Narwaz 18, 19, 89 Intersection 21 Greg Heins 29 Jeffrey Evans4, 10, 43, 47, 51 (detail), 53–57, 59, 61, 69, 73, 75 Ralph Koch 52 Christopher Gardner 58 James Prinz Photography 76 Cara Bramson 82, 87 Laura Pedrick 96, 98 Bruce M. White 74 Martin Senn 71 2 Keith Haring, American, 1958–1990. Dog, 1983. Enamel paint on incised wood. The Schorr Family Collection / © The Keith Haring Foundation 4 Frank Stella, American, born 1936. Had Gadya: Front Cover, 1984. Hand-coloring and hand-cut collage with lithograph, linocut, and screenprint. Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960 / © 2017 Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 12 Paul Wyse, Canadian, born United States, born 1970, after a photograph by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, American, born 1952. Toni Morrison (aka Chloe Anthony Wofford), 2017. Oil on canvas. Princeton University / © Paul Wyse 43 Sally Mann, American, born 1951. Under Blueberry Hill, 1991. Gelatin silver print. Museum purchase, Philip F. Maritz, Class of 1983, Photography Acquisitions Fund 2016-46 / © Sally Mann, Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery © Helen Frankenthaler Foundation 9, 46, 68, 70 © Taiye Idahor 47 © Titus Kaphar 58 © The Estate of Diane Arbus LLC 59 © Jeff Whetstone 61 © Vesna Pavlovic´ 62 © David Hockney 64 © The Henry Moore Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 65 © Mary Lee Bendolph / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York 67 © Susan Point 69 © 1973 Charles White Archive 71 © Zilia Sánchez 73 The paper is Opus 100 lb. -

Giant List of Folklore Stories Vol. 5: the United States

The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay Skim and Scan The Giant List of Folklore Stories Folklore, Folktales, Folk Heroes, Tall Tales, Fairy Tales, Hero Tales, Animal Tales, Fables, Myths, and Legends. Vol. 5: The United States Presented by Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The fastest, most effective way to teach students organized multi-paragraph essay writing… Guaranteed! Beginning Writers Struggling Writers Remediation Review 1 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay – Guaranteed Fast and Effective! © 2018 The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 5 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The Giant List of Folklore Stories – Vol. 5 This volume is one of six volumes related to this topic: Vol. 1: Europe: South: Greece and Rome Vol. 4: Native American & Indigenous People Vol. 2: Europe: North: Britain, Norse, Ireland, etc. Vol. 5: The United States Vol. 3: The Middle East, Africa, Asia, Slavic, Plants, Vol. 6: Children’s and Animals So… what is this PDF? It’s a huge collection of tables of contents (TOCs). And each table of contents functions as a list of stories, usually placed into helpful categories. Each table of contents functions as both a list and an outline. What’s it for? What’s its purpose? Well, it’s primarily for scholars who want to skim and scan and get an overview of the important stories and the categories of stories that have been passed down through history. Anyone who spends time skimming and scanning these six volumes will walk away with a solid framework for understanding folklore stories. -

Twenty-Four Conservative-Liberal Thinkers Part I Hannes H

Hannes H. Gissurarson Twenty-Four Conservative-Liberal Thinkers Part I Hannes H. Gissurarson Twenty-Four Conservative-Liberal Thinkers Part I New Direction MMXX CONTENTS Hannes H. Gissurarson is Professor of Politics at the University of Iceland and Director of Research at RNH, the Icelandic Research Centre for Innovation and Economic Growth. The author of several books in Icelandic, English and Swedish, he has been on the governing boards of the Central Bank of Iceland and the Mont Pelerin Society and a Visiting Scholar at Stanford, UCLA, LUISS, George Mason and other universities. He holds a D.Phil. in Politics from Oxford University and a B.A. and an M.A. in History and Philosophy from the University of Iceland. Introduction 7 Snorri Sturluson (1179–1241) 13 St. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) 35 John Locke (1632–1704) 57 David Hume (1711–1776) 83 Adam Smith (1723–1790) 103 Edmund Burke (1729–1797) 129 Founded by Margaret Thatcher in 2009 as the intellectual Anders Chydenius (1729–1803) 163 hub of European Conservatism, New Direction has established academic networks across Europe and research Benjamin Constant (1767–1830) 185 partnerships throughout the world. Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850) 215 Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–1859) 243 Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) 281 New Direction is registered in Belgium as a not-for-profit organisation and is partly funded by the European Parliament. Registered Office: Rue du Trône, 4, 1000 Brussels, Belgium President: Tomasz Poręba MEP Executive Director: Witold de Chevilly Lord Acton (1834–1902) 313 The European Parliament and New Direction assume no responsibility for the opinions expressed in this publication. -

1857: the Mission to Furnish Means for Episcopal Seminarians

1857: The Mission to Furnish Means for Episcopal Seminarians “The more things change the more they stay the same” might well serve as the appropriate motto for the Society for the Increase of the Ministry as it marks the 150th anniversary of its founding. SIM currently has set a course for the 21st century that requires unprecedented change in its organization and structure in order to remain faithful to its original and same purpose set forth at its founding in 1857: “The object of this corporation shall be to furnish means for the education of candidates for holy orders in the Protestant Episcopal Church of the United States.” “The Episcopal Church’s membership stood at about 400,000 in 1857 and would experience significant growth in numbers and geographical dispersion in the latter 19th century.” The need for dedicated, trained and educated ordained leaders of the Church in 2007 remains the same as in 1857, but the circumstances have changed dramatically. The United States during the term of President James Buchanan was heading for the country’s greatest crisis that would erupt into a bloody and fractious war in 1860. The frontier still beckoned settlers to fill the vast spaces that would be defended by Native Americans for several more decades. The Civil War would unleash a new wave of economic development and industrialization and the country would soon be tied together in a new way with the trans-continental railroad. Millions of immigrants would flock to our shores.A nation of 32 million has grown to the 300 million of 2006. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION in Re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMEN

USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 1 of 354 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION ) Case No. 3:05-MD-527 RLM In re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE ) (MDL 1700) SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMENT ) PRACTICES LITIGATION ) ) ) THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ) ) Carlene Craig, et. al. v. FedEx Case No. 3:05-cv-530 RLM ) Ground Package Systems, Inc., ) ) PROPOSED FINAL APPROVAL ORDER This matter came before the Court for hearing on March 11, 2019, to consider final approval of the proposed ERISA Class Action Settlement reached by and between Plaintiffs Leo Rittenhouse, Jeff Bramlage, Lawrence Liable, Kent Whistler, Mike Moore, Keith Berry, Matthew Cook, Heidi Law, Sylvia O’Brien, Neal Bergkamp, and Dominic Lupo1 (collectively, “the Named Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and the Certified Class, and Defendant FedEx Ground Package System, Inc. (“FXG”) (collectively, “the Parties”), the terms of which Settlement are set forth in the Class Action Settlement Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) attached as Exhibit A to the Joint Declaration of Co-Lead Counsel in support of Preliminary Approval of the Kansas Class Action 1 Carlene Craig withdrew as a Named Plaintiff on November 29, 2006. See MDL Doc. No. 409. Named Plaintiffs Ronald Perry and Alan Pacheco are not movants for final approval and filed an objection [MDL Doc. Nos. 3251/3261]. USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 2 of 354 Settlement [MDL Doc. No. 3154-1]. Also before the Court is ERISA Plaintiffs’ Unopposed Motion for Attorney’s Fees and for Payment of Service Awards to the Named Plaintiffs, filed with the Court on October 19, 2018 [MDL Doc. -

Of Cornell Alumni Associa- Tion: Seth W

ft \LUMNI NEWS "HINDE & DAUCH" • me- STARRING A continuous Vji performance starring the most glamorous personality of the corrugated box industry. Look for Cora Gated on your corrugated boxes! HINDE & DAUCH SANDUSKY, OHIO CORNELL HEIGHTS CLUB ONE COUNTRY CLUB ROAD ITHACA, NEW YORK TELEPHONE: 4-9933 erving CORNELLIANS and their GUESTS in ITHACA, N. Y. DAILY AND MONTHLY RATES ALL UNITS FEATURE: Large Studio Type Living-Bed Room. Your Ithaca HEADQUARTERS Complete Kitchenette. Tile Bath with Tub and Shower. Attending Summer Session, Conferences or Television or Radio. 1 Telephone Switchboard Service. Vacationing? "Write about special rates/ Fireproof ^ * Soundproof Club Food Service. "At the edge of the Campus — Across from the Country Club" The Home of THE CORNELL CLUB of Ithaca" AND THE STATE OF THE NATION JL erhaps far more than we realize, the state of our nation All of this will help to create new jobs and new oppor- depends on our state of mind. tunities in the years ahead. For if false fears can incapacitate an individual, they can All of this should help to create a state of mind that is do the same to a country, which is made up of individuals. good for the state of our nation. The people of Union Oil believe in America and its ability to continue to furnish the highest standard of living ever achieved by man. We are backing this belief this year with a nearly OF CALIFORNIA $100,000,000 vote of confidence which calls for new wells, new products, new plants, new refineries, new tankers, new Buy American and protect your standard of living trucks, new tools, new1 processes. -

AMERICAN MANHOOD in the CIVIL WAR ERA a Dissertation Submitted

UNMADE: AMERICAN MANHOOD IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Michael E. DeGruccio _________________________________ Gail Bederman, Director Graduate Program in History Notre Dame, Indiana July 2007 UNMADE: AMERICAN MANHOOD IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA Abstract by Michael E. DeGruccio This dissertation is ultimately a story about men trying to tell stories about themselves. The central character driving the narrative is a relatively obscure officer, George W. Cole, who gained modest fame in central New York for leading a regiment of black soldiers under the controversial General Benjamin Butler, and, later, for killing his attorney after returning home from the war. By weaving Cole into overlapping micro-narratives about violence between white officers and black troops, hidden war injuries, the personal struggles of fellow officers, the unbounded ambition of his highest commander, Benjamin Butler, and the melancholy life of his wife Mary Barto Cole, this dissertation fleshes out the essence of the emergent myth of self-made manhood and its relationship to the war era. It also provides connective tissue between the top-down war histories of generals and epic battles and the many social histories about the “common soldier” that have been written consciously to push the historiography away from military brass and Lincoln’s administration. Throughout this dissertation, mediating figures like Cole and those who surrounded him—all of lesser ranks like major, colonel, sergeant, or captain—hem together what has previously seemed like the disconnected experiences of the Union military leaders, and lowly privates in the field, especially African American troops. -

FRANCIS MARION UNIVERSITY DESCRIPTION of PROPOSED NEW COURSE Department/School H

FRANCIS MARION UNIVERSITY DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSED NEW COURSE Department/School HONORS Date September 16, 2013 Course No. or level HNRS 270-279 Title HONORS SPECIAL TOPICS IN THE BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES Semester hours 3 Clock hours: Lecture 3 Laboratory 0 Prerequisites Membership in FMU Honors, or permission of Honors Director Enrollment expectation 15 Indicate any course for which this course is a (an) Modification N/A Substitute N/A Alternate N/A Name of person preparing course description: Jon Tuttle Department Chairperson’s /Dean’s Signature _______________________________________ Date of Implementation Fall 2014 Date of School/Department approval: September 13, 2013 Catalog description: 270-279 SPECIAL TOPICS IN THE BEHAVIORAL SCIENCES (3) (Prerequisite: membership in FMU Honors or permission of Honors Director.) Course topics may be interdisciplinary and cover innovative, non-traditional topics within the Behavioral Sciences. May be taken for General Education credit as an Area 4: Humanities/Social Sciences elective. May be applied as elective credit in applicable major with permission of chair or dean. Purpose: 1. For Whom (generally?): FMU Honors students, also others students with permission of instructor and Honors Director 2. What should the course do for the student? HNRS 270-279 will offer FMU Honors members enhanced learning options within the Behavioral Sciences beyond the common undergraduate curriculum and engage potential majors with unique, non-traditional topics. Teaching method/textbook and materials planned: Lecture, -

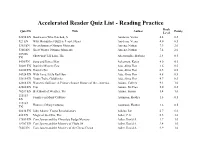

Accelerated Reader Quiz List

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Book Quiz ID Title Author Points Level 32294 EN Bookworm Who Hatched, A Aardema, Verna 4.4 0.5 923 EN Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People's Ears Aardema, Verna 4.0 0.5 5365 EN Great Summer Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.9 2.0 5366 EN Great Winter Olympic Moments Aaseng, Nathan 7.4 2.0 107286 Show-and-Tell Lion, The Abercrombie, Barbara 2.4 0.5 EN 5490 EN Song and Dance Man Ackerman, Karen 4.0 0.5 50081 EN Daniel's Mystery Egg Ada, Alma Flor 1.6 0.5 64100 EN Daniel's Pet Ada, Alma Flor 0.5 0.5 54924 EN With Love, Little Red Hen Ada, Alma Flor 4.8 0.5 35610 EN Yours Truly, Goldilocks Ada, Alma Flor 4.7 0.5 62668 EN Women's Suffrage: A Primary Source History of the...America Adams, Colleen 9.1 1.0 42680 EN Tipi Adams, McCrea 5.0 0.5 70287 EN Best Book of Weather, The Adams, Simon 5.4 1.0 115183 Families in Many Cultures Adamson, Heather 1.6 0.5 EN 115184 Homes in Many Cultures Adamson, Heather 1.6 0.5 EN 60434 EN John Adams: Young Revolutionary Adkins, Jan 6.7 6.0 480 EN Magic of the Glits, The Adler, C.S. 5.5 3.0 17659 EN Cam Jansen and the Chocolate Fudge Mystery Adler, David A. 3.7 1.0 18707 EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of Flight 54 Adler, David A. 3.4 1.0 7605 EN Cam Jansen and the Mystery of the Circus Clown Adler, David A. -

Henryk Siemiradzki and the International Artistic Milieu

ACCADEMIA POL ACCA DELLE SCIENZE DELLE SCIENZE POL ACCA ACCADEMIA BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA E CENTRO BIBLIOTECA ACCADEMIA POLACCA DELLE SCIENZE BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA CONFERENZE 145 HENRYK SIEMIRADZKI AND THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTIC MILIEU FRANCESCO TOMMASINI, L’ITALIA E LA RINASCITA E LA RINASCITA L’ITALIA TOMMASINI, FRANCESCO IN ROME DELLA INDIPENDENTE POLONIA A CURA DI MARIA NITKA AGNIESZKA KLUCZEWSKA-WÓJCIK CONFERENZE 145 ACCADEMIA POLACCA DELLE SCIENZE BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA ISSN 0239-8605 ROMA 2020 ISBN 978-83-956575-5-9 CONFERENZE 145 HENRYK SIEMIRADZKI AND THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTIC MILIEU IN ROME ACCADEMIA POLACCA DELLE SCIENZE BIBLIOTECA E CENTRO DI STUDI A ROMA CONFERENZE 145 HENRYK SIEMIRADZKI AND THE INTERNATIONAL ARTISTIC MILIEU IN ROME A CURA DI MARIA NITKA AGNIESZKA KLUCZEWSKA-WÓJCIK. ROMA 2020 Pubblicato da AccademiaPolacca delle Scienze Bibliotecae Centro di Studi aRoma vicolo Doria, 2 (Palazzo Doria) 00187 Roma tel. +39 066792170 e-mail: [email protected] www.rzym.pan.pl Il convegno ideato dal Polish Institute of World Art Studies (Polski Instytut Studiów nad Sztuką Świata) nell’ambito del programma del Ministero della Scienza e dell’Istruzione Superiore della Repubblica di Polonia (Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education) “Narodowy Program Rozwoju Humanistyki” (National Programme for the Develop- ment of Humanities) - “Henryk Siemiradzki: Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings” (“Tradition 1 a”, no. 0504/ nprh4/h1a/83/2015). Il convegno è stato organizzato con il supporto ed il contributo del National Institute of Polish Cultural Heritage POLONIKA (Narodowy Instytut Polskiego Dziedzictwa Kul- turowego za Granicą POLONIKA). Redazione: Maria Nitka, Agnieszka Kluczewska-Wójcik Recensione: Prof. -

The Politics and Culture of Literacy in Georgia, 1800-1920

THE POLITICS AND CULTURE OF LITERACY IN GEORGIA, 1800-1920 Bruce Fort Atlanta, Georgia B. A., Georgetown University, 1985 M.A., University of Virginia, 1989 A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Corcoran Department of History University of Virginia August 1999 © Copyright by Bruce Fort All Rights Reserved August 1999 ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the uses and meanings of reading in the nineteenth century American South. In a region where social relations were largely defined by slavery and its aftermath, contests over education were tense, unpredictable, and frequently bloody. Literacy figured centrally in many of the region's major struggles: the relationship between slaveowners and slaves, the competing efforts to create and constrain black freedom following emancipation, and the disfranchisement of black voters at the turn of the century. Education signified piety and propriety, self-culture and self-control, all virtues carefully cultivated and highly prized in nineteenth-century America. Early advocates of public schooling argued that education and citizenship were indissociable, a sentiment that was refined and reshaped over the course of the nineteenth century. The effort to define this relationship, throughout the century a leitmotif of American public life, bubbled to the surface in the South at critical moments: during the early national period, as Americans sought to put the nation's founding principles into motion; during the 1830s, as insurrectionists and abolitionists sought to undermine slavery; during Reconstruction, with the institution of black male citizenship; and at last, during the disfranchisement movement of the 1890s and 1900s, with the imposition of literacy tests. -

Influence of Cavity Availability on Red-Cockaded Woodpecker Group Size

Wilson Bulletin, 110(l), 1998, pp. 93-99 INFLUENCE OF CAVITY AVAILABILITY ON RED-COCKADED WOODPECKER GROUP SIZE N. ROSS CARRIE,,*‘ KENNETH R. MOORE, ’ STEPHANIE A. STEPHENS, ’ AND ERIC L. KEITH ’ ABSTRACT-The availability of cavities can determine whether territories are occupied by Red-cockaded Woodpeckers (Picoides borealis). However, there is no information on whether the number of cavities can influence group size and population stability. We compared group size between 1993 and 1995 in 33 occupied cluster sites that were provisioned with artificial cavities. The number of groups with breeding pairs increased from 22 (67.7%) in 1993 to 28 (93.3%) in 1995. Most breeding males remained in the natural cavities that they had excavated and occupied prior to cavity provisioning in the cluster while breeding females and helpers used artificial cavities extensively. Active cluster sites provisioned with artificial cavities had larger social groups in 1995 (3 = 2.70, SD = 1.42) than in 1993 (3 = 2.00, SD = 0.94; Z = -2.97, P = 0.003). The number of suitable cavities per cluster was positively correlated with the number of birds per cluster (rJ = 0.42, P = 0.016). The number of inserts per cluster was positively correlated with the change in group size between 1993 and 1995 (r, = 0.49, P = 0.004). Our observations indicate that three or four suitable cavities should be maintained uer cluster to stabilize and/or increase Red-cockaded Woodpecker populations. Received 3 March 1997, accepted 57 Oct. 1997. The Red-cockaded Woodpecker (Picoides numbers of old-growth trees for cavity exca- borealis) is an endangered species endemic to vation.