The Behaviour of Skylarks Juan D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Inventory of Avian Species in Aldesa Valley, Saudi Arabia

14 5 LIST OF SPECIES Check List 14 (5): 743–750 https://doi.org/10.15560/14.5.743 An inventory of avian species in Aldesa Valley, Saudi Arabia Abdulaziz S. Alatawi1, Florent Bled1, Jerrold L. Belant2 1 Mississippi State University, Forest and Wildlife Research Center, Carnivore Ecology Laboratory, Box 9690, Mississippi State, MS, USA 39762. 2 State University of New York, College of Environmental Science and Forestry, 1 Forestry Drive, Syracuse, NY, USA 13210. Corresponding author: Abdulaziz S. Alatawi, [email protected] Abstract Conducting species inventories is important to provide baseline information essential for management and conserva- tion. Aldesa Valley lies in the Tabuk Province of northwest Saudi Arabia and because of the presence of permanent water, is thought to contain high avian richness. We conducted an inventory of avian species in Aldesa Valley, using timed area-searches during May 10–August 10 in 2014 and 2015 to detect species occurrence. We detected 6860 birds belonging to 19 species. We also noted high human use of this area including agriculture and recreational activities. Maintaining species diversity is important in areas receiving anthropogenic pressures, and we encourage additional surveys to further identify species occurrence in Aldesa Valley. Key words Arabian Peninsula; bird inventory; desert fauna. Academic editor: Mansour Aliabadian | Received 21 April 2016 | Accepted 27 May 2018 | Published 14 September 2018 Citation: Alatawi AS, Bled F, Belant JL (2018) An inventory of avian species in Aldesa Valley, Saudi Arabia. Check List 14 (5): 743–750. https:// doi.org/10.15560/14.5.743 Introduction living therein (Balvanera et al. -

New Data on the Chewing Lice (Phthiraptera) of Passerine Birds in East of Iran

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/244484149 New data on the chewing lice (Phthiraptera) of passerine birds in East of Iran ARTICLE · JANUARY 2013 CITATIONS READS 2 142 4 AUTHORS: Behnoush Moodi Mansour Aliabadian Ferdowsi University Of Mashhad Ferdowsi University Of Mashhad 3 PUBLICATIONS 2 CITATIONS 110 PUBLICATIONS 393 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Ali Moshaverinia Omid Mirshamsi Ferdowsi University Of Mashhad Ferdowsi University Of Mashhad 10 PUBLICATIONS 17 CITATIONS 54 PUBLICATIONS 152 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Available from: Omid Mirshamsi Retrieved on: 05 April 2016 Sci Parasitol 14(2):63-68, June 2013 ISSN 1582-1366 ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE New data on the chewing lice (Phthiraptera) of passerine birds in East of Iran Behnoush Moodi 1, Mansour Aliabadian 1, Ali Moshaverinia 2, Omid Mirshamsi Kakhki 1 1 – Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Faculty of Sciences, Department of Biology, Iran. 2 – Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Pathobiology, Iran. Correspondence: Tel. 00985118803786, Fax 00985118763852, E-mail [email protected] Abstract. Lice (Insecta, Phthiraptera) are permanent ectoparasites of birds and mammals. Despite having a rich avifauna in Iran, limited number of studies have been conducted on lice fauna of wild birds in this region. This study was carried out to identify lice species of passerine birds in East of Iran. A total of 106 passerine birds of 37 species were captured. Their bodies were examined for lice infestation. Fifty two birds (49.05%) of 106 captured birds were infested. Overall 465 lice were collected from infested birds and 11 lice species were identified as follow: Brueelia chayanh on Common Myna (Acridotheres tristis), B. -

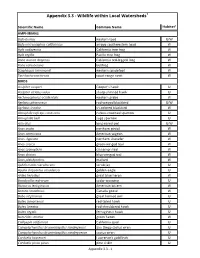

Appendix 3.3 - Wildlife Within Local Watersheds1

Appendix 3.3 - Wildlife within Local Watersheds1 2 Scientific Name Common Name Habitat AMPHIBIANS Bufo boreas western toad U/W Bufo microscaphus californicus arroyo southwestern toad W Hyla cadaverina California tree frog W Hyla regilla Pacific tree frog W Rana aurora draytonii California red-legged frog W Rana catesbeiana bullfrog W Scaphiopus hammondi western spadefoot W Taricha torosa torosa coast range newt W BIRDS Accipiter cooperi Cooper's hawk U Accipiter striatus velox sharp-shinned hawk U Aechmorphorus occidentalis western grebe W Agelaius phoeniceus red-winged blackbird U/W Agelaius tricolor tri-colored blackbird W Aimophila ruficeps canescens rufous-crowned sparrow U Aimophilia belli sage sparrow U Aiso otus long-eared owl U/W Anas acuta northern pintail W Anas americana American wigeon W Anas clypeata northern shoveler W Anas crecca green-winged teal W Anas cyanoptera cinnamon teal W Anas discors blue-winged teal W Anas platrhynchos mallard W Aphelocoma coerulescens scrub jay U Aquila chrysaetos canadensis golden eagle U Ardea herodius great blue heron W Bombycilla cedrorum cedar waxwing U Botaurus lentiginosus American bittern W Branta canadensis Canada goose W Bubo virginianus great horned owl U Buteo jamaicensis red-tailed hawk U Buteo lineatus red-shouldered hawk U Buteo regalis ferruginous hawk U Butorides striatus green heron W Callipepla californica California quail U Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus sandiegensis San Diego cactus wren U Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus sandiegoense cactus wren U Carduelis lawrencei Lawrence's -

Morphology, Diet Composition, Distribution and Nesting Biology of Four Lark Species in Mongolia

© 2013 Journal compilation ISSN 1684-3908 (print edition) http://biology.num.edu.mn Mongolian Journal of Biological http://mjbs.100zero.org/ Sciences MJBS Volume 11(1-2), 2013 ISSN 2225-4994 (online edition) Original ArƟ cle Morphology, Diet Composition, Distribution and Nesting Biology of Four Lark Species in Mongolia Galbadrakh Mainjargal1, Bayarbaatar Buuveibaatar2* and Shagdarsuren Boldbaatar1 1Laboratory of Ornithology, Institute of Biology, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, Jukov Avenue, Ulaanbaatar 51, Mongolia, Email: [email protected] 2Mongolia Program, Wildlife Conservation Society, San Business Center 201, Amar Str. 29, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, email: [email protected] Abstract Key words: We aimed to enhance existing knowledge of four lark species (Mongolian lark, Horned Alaudidae, larks, lark, Eurasian skylark, and Lesser short-toed lark), with respect to nesting biology, breeding, food habits, distribution, and diet, using long-term dataset collected during 2000–2012. Nest and Mongolia egg measurements substantially varied among species. For pooled data across species, the clutch size averaged 3.72 ± 1.13 eggs and did not differ among larks. Body mass of nestlings increased signifi cantly with age at weighing. Daily increase in body mass Article information: of lark nestlings ranged between 3.09 and 3.89 gram per day. Unsurprisingly, the Received: 18 Nov. 2013 majority of lark locations occurred in steppe ecosystems, followed by human created Accepted: 11 Dec. 2013 systems; whereas only 1.8% of the pooled locations across species were observed in Published: 20 Apr. 2014 forest ecosystem. Diet composition did not vary among species in the proportions of major food categories consumed. The most commonly occurring food items were invertebrates and frequently consumed were being beetles (e.g. -

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

Taxonomy of the Mirafra Assamica Complex

FORKTAIL 13 (1998): 97-107 Taxonomy of the Mirafra assamica complex PER ALSTROM Four taxa are recognised in the Mirafra assamicacomplex: assamica Horsfield, affinis Blyth, microptera Hume, and marionae Baker; subsessorDeignan is considered to be a junior synonym of marionae. These four taxa differ in morphology and especially in vocalizations. Both assamicaand microptera have diagnostic song-flights, while affinis and marionae have similar song-flights. There are also differences in other behavioural aspects and habitat between assamicaand the others. On account of this, it is suggested that Mirafra assamicasensu lato be split into four species:M assamica,M affinis,M micropteraand M marionae.English names proposed are: Bengal Bushlark, ] erdon' s Bushlark, Burmese Bushlark and Indochinese Bushlark, respectively. The Rufous-winged Bushlark Mirafra assamica Horsfield (including the holotype) on my behalf in the Smithsonian is usually divided into five subspecies: assamica Horsfield Institution, Washington, D.C., USA. I have examined c. (1840), affinis Blyth (1845), microptera Hume (1873), 20 specimens of ceylonensis, though I have not compared it subsessor Deignan (1941), and marionae Baker (1915) in detail with affinis, and I have only measured four (Peters 1960, Howard and Moore 1991). One further specimens (of which two were unsexed). For all taxa, taxon, ceylonensis Whistler (1936), is sometimes recognized, measurements of wing length (with the wing flattened and but following Ripley (1946) and Vaurie (1951) most recent stretched; method 3, Svensson 1992), tail length, bill length authors treat it as a junior synonym of affinis. The name (to skull), bill depth (at distal end of nostrils), tarsus length marionae is actually predated by erythrocephala Salvadori and hind-claw length were taken of specimens whose labels and Giglioli (1885), but this does not appear to have been indicated their sex. -

Of Larks, Owls and Unusual Diets and Feeding Habits V

Of larks, owls and unusual diets and feeding habits V. Santharam Santharam, V. 2008. Of larks, owls and unusual diets and feeding habits. Indian Birds 4 (2): 68–69. V. Santharam, Institute of Bird Studies & Natural History, Rishi Valley Education Centre, Rishi Valley 517352, Chittoor District, Andhra Pradesh, India. Email: [email protected] Mss received on 17th December 2007. A day with the larks the presence of the distinctly long crest, which when flattened, 18th January 2007: Suresh Jones and I were off on waterfowl reached the upper nape. There were at least four birds present counts at some wetlands near Rishi Valley, (Andhra Pradesh, that morning. India). It was a cool and crisp morning with clear skies. After a The last species of the day was the common Ashy-crowned year of rains the wetlands had begun drying up. We knew there Sparrow-Lark Eremopterix grisea, which was noticed in the more would be fewer birds for us to count this year. We were least drier, open country. The prized sighting that morning was an bothered since we were sure to find other interesting birds. albino specimen fluttering about in the stiff breeze like a sheet of I was just telling Suresh that I have, in the past, seen Indian paper (which we mistook it for, initially!). Its plumage, including Eagle-Owls Bubo benghalensis perched on roadside electric posts, the beak, was pinkish white. Its eye appeared darker and there when a dead Indian Eagle-Owl, on the road, drew our attention. was a faint pinkish wash on its breast and tail. -

Skylark Free Download

SKYLARK FREE DOWNLOAD MacLachlan | 112 pages | 03 Aug 2004 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780064406222 | English | New York, NY, United States To All Our Friends & Guests Sound Mix: Stereo. This adaptation for more efficient hovering flight may have evolved because of Skylark Eurasian skylarks' preference for males that sing and hover for longer periods Skylark so demonstrate that they are likely to have good overall fitness. Available on Amazon. The Eurasian skylark walks over the ground searching for food on the soil surface. Recent Examples on the Web: Noun Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni is home to a variety of wildlife, and surveys conducted in noted skylarksospreys, and peregrine falcons—among other birds—nesting on the base. The only thing you'll need to worry about is Skylark to read on the plane. Get Word of the Day delivered Skylark your inbox! Crazy Credits. Round trip flights and hotel for 2 - what you see is what you pay. Metacritic Reviews. Chub 'Chubbers' Horatio. Maggie : [ Wiping eyes, voice breaking ] Sarah. The verb and noun "lark", with Skylark meaning, may be related to "skylark" or to the dialect word "laik" New Shorter OED. Runtime: Skylark min. Retrieved 14 February Yes No Report this. Rooms Error Skylark. The Skylark population increased rapidly and had spread throughout both Skylark North and Skylark Islands by the s. Chub 'Chubbers' Horatio Lois Smith Canadian Field-Naturalist. Featured Skylark : Washington, Connecticut. Retrieved 5 August Do you know the person or Skylark these quotes desc Dunn's lark. Short-clawed lark Karoo long-billed lark Benguela long-billed lark Eastern long-billed lark Cape long-billed lark Agulhas long-billed lark. -

Nest Survival in Year-Round Breeding Tropical Red-Capped Larks

University of Groningen Nest survival in year-round breeding tropical red-capped larks Calandrella cinerea increases with higher nest abundance but decreases with higher invertebrate availability and rainfall Mwangi, Joseph; Ndithia, Henry K.; Kentie, Rosemarie; Muchai, Muchane; Tieleman, B. Irene Published in: Journal of Avian Biology DOI: 10.1111/jav.01645 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2018 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Mwangi, J., Ndithia, H. K., Kentie, R., Muchai, M., & Tieleman, B. I. (2018). Nest survival in year-round breeding tropical red-capped larks Calandrella cinerea increases with higher nest abundance but decreases with higher invertebrate availability and rainfall. Journal of Avian Biology, 49(8), [01645]. https://doi.org/10.1111/jav.01645 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. -

(Alaudala Rufescens) — Sand Lark (A

Received: 11 October 2019 | Revised: 10 February 2020 | Accepted: 18 March 2020 DOI: 10.1111/zsc.12422 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Densely sampled phylogenetic analyses of the Lesser Short- toed Lark (Alaudala rufescens) — Sand Lark (A. raytal) species complex (Aves, Passeriformes) reveal cryptic diversity Fatemeh Ghorbani1 | Mansour Aliabadian1,2 | Ruiying Zhang3 | Martin Irestedt4 | Yan Hao3 | Gombobaatar Sundev5 | Fumin Lei3 | Ming Ma6 | Urban Olsson7,8 | Per Alström3,9 1Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran 2Zoological Innovations Research Department, Institute of Applied Zoology, Faculty of Science, Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran 3Key Laboratory of Zoological Systematics and Evolution, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 4Department of Bioinformatics and Genetics, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm, Sweden 5National University of Mongolia and Mongolian Ornithological Society, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia 6Xinjiang Institute of Ecology and Geography, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xinjiang, China 7Systematics and Biodiversity, Department of Biology and Environmental Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Göteborg, Sweden 8Gothenburg Global Biodiversity Centre, Gothenburg, Sweden 9Animal Ecology, Department of Ecology and Genetics, Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden Correspondence Mansour Aliabadian, Department of Abstract Biology, Faculty of Science, Ferdowsi The taxonomy of the Lesser/Asian Short-toed Lark Alaudala rufescens–cheleensis University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran. complex has been debated for decades, mainly because of minor morphological dif- Email: [email protected] ferentiation among the taxa within the complex, and different interpretations of the Per Alström, Animal Ecology, Department geographical pattern of morphological characters among different authors. In addi- of Ecology and Genetics, Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, tion, there have been few studies based on non-morphological traits. -

Do Migrant and Resident Species Differ in the Timing Of

Zhao et al. Avian Res (2017) 8:10 DOI 10.1186/s40657-017-0068-3 Avian Research RESEARCH Open Access Do migrant and resident species difer in the timing of increases in reproductive and thyroid hormone secretion and body mass? A case study in the comparison of pre‑breeding physiological rhythms in the Eurasian Skylark and Asian Short‑toed Lark Lidan Zhao1, Lijun Gao1, Wenyu Yang1, Xianglong Xu1, Weiwei Wang1, Wei Liang2 and Shuping Zhang1* Abstract Background: Physiological preparation for reproduction in small passerines involves the increased secretion of reproductive hormones, elevation of the metabolic rate and energy storage, all of which are essential for reproduc- tion. However, it is unclear whether the timing of the physiological processes involved is the same in resident and migrant species that breed in the same area. To answer this question, we compared temporal variation in the plasma concentration of luteinizing hormone (LH), testosterone (T), estradiol (E2), triiothyronine (T3) and body mass, between a migrant species, the Eurasian Skylark (Alauda arvensis) and a resident species, the Asian Short-toed Lark (Calandrella cheleensis), both of which breed in northeastern Inner Mongolia, China, during the 2014 and 2015 breeding seasons. Methods: Twenty adult Eurasian Skylarks and twenty Asian Short-toed Larks were captured on March 15, 2014 and 2015 and housed in out-door aviaries. Plasma LH, T (males), E2 (females), T3 and the body mass of each bird were measured every six days from March 25 to May 6. Results: With the exception of T, which peaked earlier in the Asian Short-toed Lark in 2014, plasma concentrations of LH, T, E2 andT3 of both species peaked at almost the same time. -

Breeding Ecology and Population Decline of the Crested Lark Galerida Cristata in Warsaw, Poland

Ornis Hungarica (2009) 17-18: 1-11. Breeding ecology and population decline of the crested lark Galerida cristata in Warsaw, Poland G. Lesiński Lesiński, G. 2009. Breeding ecology and population decline of the crested lark Galerida crista- ta in Warsaw, Poland – Ornis Hung. 17-18: 1-11. Abstract The crested lark Galerida cristata inhabited almost exclusively open areas in the out- skirts of new settlements of Warsaw in the years 1980-2006. The highest density of the species (0.11 pairs/km2) in the entire city (494 km2) was recorded in 1986, and locally (a plot of 2.6 km2) – 5.7 pairs/km2 in 1980. Breeding period lasted from April 12th (the first egg) to July 31st (the last fledgeling) with broods most inten- sively initiated in May. There were usually 4-5 eggs per brood, rarely 3 (mean 4.36±0.60 sD). The mean number of eggs in the first brood was 4.47±0.64 eggs, in the first repeated brood – 4.17±0.98 eggs and in the second brood – 4.09±0.70 eggs. Most pairs (71%) performed the second brood. Reproductive success of the population of 17 pairs studied in 1980 was 3.47 fledgelings leaving the nest per nesting pair (nearly 40% of broods were destroyed). Breeding losses resulted mostly from human activity and intensive rainfalls. Population of G. cristata in Warsaw was characterized by a great dynamics. None of the 17 pairs living on the plot of 2.6 km2 in 1980 remained in 1987 due to the management of new settlements.