Commodity Fetishism, ‘Tradition’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mom's English Fruitcake This Recipe Comes from Nicholas Lodge's Mother, and He Writes, "This Is the Holiday Fruitcake That I Grew up With

Mom's English Fruitcake This recipe comes from Nicholas Lodge's Mother, and he writes, "This is the holiday fruitcake that I grew up with. I have very fond memories of making these traditional cakes with my Mother and Grandmother as well. I hope you start a holiday tradition as well with these cakes. I do have a warning for you, this recipe makes two generous five-pound cakes. Get out your largest mixing bowl and have fun!" 4 cups all-purpose flour, divided 1 cup whole milk 1 pound dates, chopped 3/4 cup light corn syrup 1 pound candied citron, optional 2 teaspoons baking soda 1 pound pecans, chopped 2 teaspoons ground nutmeg 1 pound figs, coarsely chopped 2 teaspoons ground allspice 1 (15 oz.) box raisins 1 teaspoon baking powder 1 (10 oz.) box currants 1 cup brandy 1 cup butter, softened plus additional brandy for soaking 2 cups white granulated sugar 12 large eggs Grease and flour 2 (10 inch) tube pans, then line with parchment paper and grease and flour the parchment paper as well and set aside. Combine 1/2 cup flour, and the next 6 ingredients in a large bowl. Toss lightly to coat and set aside. Beat butter at medium speed with an electric mixer until creamy. Slowly add the sugar. Add the eggs, one at a time, beating well until blended after each addition. Add milk and corn syrup and mix well. Combine the remaining 3½ cups flour, baking soda and next 4 ingredients. Add to the butter mixture alternately with the 1 cup of brandy, beginning and ending with the dry mixture. -

Everyone's Favorite Fruitcake Recipe Bundle

WELCOME TO YOUR EVERYONE'S FAVORITE FRUITCAKE RECIPE BUNDLE Included: Bundt Quartet Pan, Fruitcake Fruit Blend, Candied Orange Peel, Candied Lemon Peel, Mini Diced Crystallized Ginger, Vietnamese Cinnamon (1.5 oz.), Allspice, Nutmeg, Boiled Cider, and Ginger Syrup. HANDS-ON TIME: 30 mins. | BAKING TIME: 70 mins. to 75 mins. | TOTAL TIME: 2 hrs. 50 mins. | YIELD: 6 mini Bundt cakes INGREDIENTS INSTRUCTIONS FRUIT 1 To prepare the fruit: Combine fruit with liquid of choice in a nonreactive bowl; cover and let rest overnight. Alternatively, microwave everything for 1 minute (or until it's very about 4 cups (567g) Fruitcake Fruit hot), cover, and let rest 1 hour. Blend 2 ⅔ cups (227g) Candied Orange and/or 2 Preheat the oven to 300°F. Candied Lemon Peel 3 To make the batter: Beat together the butter and sugar in a large (6-quart) mixing bowl. heaping 1 cup (170g) candied red Beat in salt, spices, and baking powder, then eggs one at a time, scraping bowl after each cherries; optional addition. 1/3 cup (64g) Mini Diced Crystallized 4 Add flour and boiled cider to the batter, beating gently to combine. Stir in the juice or Ginger water, then the fruit with any collected liquid, and optional nuts. Scrape the bottom and ¾ cup (170g) rum, brandy, apple juice, sides of the bowl and stir until well combined. or cranberry juice 5 Scoop the batter into the lightly greased wells of a Bundt Quartet Pan, filling them to BATTER within 1/4" of the top; if you have a scale, you'll add between 400g and 465g of batter to each well (the highest amount if you've added cherries and nuts, lower if you've omitted 1 cup (227g) soft unsalted butter them, and in between if you've only added one or the other). -

The British Isles

The British Isles Historic Society Heritage, History, Traditions & Customs OUR BRITISH ISLES HERITAGE houses the countries of England, Scotland and Wales within its shores. The British Isles The British Isles is the name of a group of islands situated off the north western corner of mainland Europe. It is made up of Great Britain, Ireland, The Isle of Man, The Isles of Sicily, The Channel Islands (including Guernsey, Jersey, Sark Dear Readers: and Alderney), as well as over 6,000 other smaller I know some of the articles in this Issue may islands. England just like Wales (Capital - Cardiff) and seem like common sense and I am researching facts Scotland (Capital - Edinburgh), North Ireland (Capital known by everyone already. But this newsletter has - Belfast) England is commonly referred to as a a wider distribution than just Ex-Pats. country, but it is not a sovereign state. It is the largest country within the United Kingdom both by Many believe Britain or Great Britain to be all landmass and population, has taken a role in the the islands in the British Isles. When we held the two creation of the UK, and its capital London is also the Heritage Festivals we could not call it a British capital of the UK. Festival because it included, England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, Cornwall and the Isle of Man. The Republic of Ireland (EIRE) Republic of What is the Difference between Britain and the Ireland is part of the British Isles, its people are not United Kingdom? British, they are distinctly Irish. It’s capital is Dublin. -

![BBC Voices Recordings: Nottingham [Meadows]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2893/bbc-voices-recordings-nottingham-meadows-342893.webp)

BBC Voices Recordings: Nottingham [Meadows]

BBC VOICES RECORDINGS http://sounds.bl.uk Title: Nottingham Shelfmark: C1190/26/05 Recording date: 17.11.2004 Speakers: Amelia, b. 1963; Nottingham; female (father b. St Kitts; mother b. St Kitts) Lauren, b. 1989; Nottingham; female; school student Rosalind, b. 1964; Nottingham; female (father b. St Kitts; mother b. St Kitts) Valerie, b. 1965; Nottingham; female (father b. St Kitts; mother b. St Kitts) Amelia, Rosalind and Valerie are sisters whose parents came to the UK from St Kitts in the 1950s; Lauren is their niece. ELICITED LEXIS ○ see English Dialect Dictionary (1898-1905) ▲see Dictionary of Jamaican English (1980) ● see Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage (1996) ♠ see Dictionary of the English/Creole of Trinidad & Tobago (2009) ▼ see Ey Up Mi Duck! Dialect of Derbyshire and the East Midlands (2000) ∆ see New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English (2006) ◊ see Green’s Dictionary of Slang (2010) ♦ see Urban Dictionary (online) ⌂ no previous source (with this sense) identified pleased (not discussed) tired (not discussed) unwell sick; “me na feel too good”1 (used by mother/older black speakers) hot (not discussed) cold (not discussed) annoyed (not discussed) throw (not discussed) 1 See Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage (1996, p.407) for use of ‘no/na’ as negative marker in Caribbean English and for spelling of markedly dialectal/Creole pronunciations, e.g. the (<de>), there (<deh>). http://sounds.bl.uk Page 1 of 27 BBC Voices Recordings play truant skive; nick off∆; skank◊; wag, wag off school, wag off (suggested -

Tabla Composición De Alimentos REIMPRESIÓN

INSTITUTO DE NUTRICIÓN DE CENTRO AMÉRICA Y PANAMÁ (INCAP) ORGANIZACIÓN PANAMERICANA DE LA SALUD (OPS) INCAP INCAP http://www.incap.int Segunda Edición © Copyright 2006 Guatemala, Centroamérica Tercera reimpresión Febrero 2012 INSTITUTO DE NUTRICIÓN DE CENTRO AMÉRICA Y PANAMÁ (INCAP) ORGANIZACIÓN PANAMERICANA DE LA SALUD (OPS) INCAP Tercera reimpresión, 2012 ME/085.3 2007 INCAP. Tabla de Composición de Alimentos de Centroamérica./INCAP/ Menchú, MT (ed); Méndez, H. (ed). Guatemala: INCAP/OPS, 2007. 2ª. Edición. viii - 128 pp. I.S.B.N. 99922-880-2-7 1. ANÁLISIS DE LOS ALIMENTOS 2. ALIMENTOS 3. VALOR NUTRITIVO Responsables de la producción de esta edición: Revisión y actualización técnica Licda. María Teresa Menchú Lic. Humberto Méndez, INCAP Coordinación de la edición y publicación Licda. Norma Alfaro, INCAP Segunda Edición Segunda reimpresión, 2009. Tercera reimpresión, 2012. Impresión: Serviprensa, S.A. PBX: 2245 8888 Tabla de Composición de Alimentos de Centroamérica Contenido Presentación................................................................................................................... v Introducción ..................................................................................................................vii Parte I. Documentación A. Antecedentes .............................................................................................................3 B. Metodología aplicada .................................................................................................. 4 C. Presentación de la Tabla de Composición -

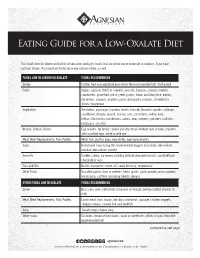

Eating Guide for a Low-Oxalate Diet

Eating Guide for a Low-Oxalate Diet This chart from the American Dietetic Association spotlights foods that are either low or moderate in oxalates. If you have calcium stones, it is important to decrease you sodium intake, as well. FOODS LOW IN SODIUM OR OXALATE FOODS RECOMMENDED Drinks Coffee, fruit and vegetable juice (from the recommended list), fruit punch Fruits Apples, apricots (fresh or canned), avocado, bananas, cherries (sweet), cranberries, grapefruit, red or green grapes, lemon and lime juice, melons, nectarines, papayas, peaches, pears, pineapples, oranges, strawberries (fresh), tangerines Vegetables Artichokes, asparagus, bamboo shoots, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, cauliflower, chayote squash, chicory, corn, cucumbers, endive, kale, lettuce, lima beans, mushrooms, onions, peas, peppers, potatoes, radishes, rutabagas, zucchini Breads, Cereals, Grains Egg noodles, rye bread, cooked and dry cereals without nuts or bran, crackers with unsalted tops, white or wild rice Meat, Meat Replacements, Fish, Poultry Meat, fish, poultry, eggs, egg whites, egg replacements Soup Homemade soup (using the recommended veggies and meat), low-sodium bouillon, low-sodium canned Desserts Cookies, cakes, ice cream, pudding without chocolate or nuts, candy without chocolate or nuts Fats and Oils Butter, margarine, cream, oil, salad dressing, mayonnaise Other Foods Unsalted potato chips or pretzels, herbs (garlic, garlic powder, onion powder), lemon juice, salt free seasoning blends, vinegar OTHER FOODS LOW IN OXALATE FOODS RECOMMENDED Drinks Beer, cola, wine, buttermilk, lemonade or limeade (without added vitamin C), milk Meat, Meat Replacements, Fish, Poultry Lunch meat, ham, bacon, hot dogs, bratwurst, sausage, chicken nuggets, cheddar cheese, canned fish and shellfish Soup Tomato soup, cheese soup Other Foods Coconuts, lemon or lime juices, sugar or sweeteners, jellies or jams (from the recommended list) (continued on next page) agnesian.com Eating Guide for a Low-Oxalate Diet, cont. -

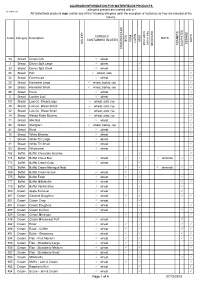

Of 4 07/12/2015

ALLERGEN INFORMATION FOR WATERFIELDS PRODUCTS - allergens present are marked with a NETHERTON All Waterfields products may contain any of the following allergens (with the exception of molluscs) as they are handled at the bakery. CEREALS Code Category Description NUTS CONTAINING GLUTEN EGG FISH MILK SOYA LUPIN CELERY SESAME (not on site) PEANUTS MOLLUSCS MUSTARD SULPHITES CRUSTACEANS 34 Bread Crown Cob wheat 3 Bread Devon Split Large wheat 33 Bread Devon Split Small wheat 85 Bread Farl wheat, oats 32 Bread Farmhouse wheat 20 Bread Harvester Large wheat, barley, rye 84 Bread Harvester Small wheat, barley, rye 86 Bread Hovis wheat 2 Bread London Loaf wheat 107 Bread Low G.I. Bread Large wheat, oats, rye 48 Bread Low G.I. Bread Sliced wheat, oats, rye 42 Bread Low G.I. Bread Small wheat, oats, rye 14 Bread Malted Flake Bloomer wheat, oats, rye 71 Bread Milk Roll wheat 88 Bread Multigrain wheat, barley, rye 41 Bread Rural wheat 16 Bread White Bloomer wheat 1 Bread White Tin Large wheat 31 Bread White Tin Small wheat 53 Bread Wholemeal wheat 782 Buffet Buffet Chocolate Surprise 774 Buffet Buffet Choux Bun wheat almonds 773 Buffet Buffet Cream Crisp wheat 778 Buffet Buffet Cream Meringue Nest almonds 786 Buffet Buffet Cream Scone wheat 775 Buffet Buffet Éclair wheat 777 Buffet Buffet Millefeuille wheat 776 Buffet Buffet Vanilla Slice wheat 500 Cream Apple Turnover wheat 467 Cream Caramel Doughnut wheat 501 Cream Cream Crisp wheat 481 Cream Cream Doughnut -

Jgonzalez 30639027 Job 8

CHAPTER 9 Working with Styles Lesson Overview In this introduction to working with InDesign styles, you’ll learn how to do the following: ◊ Create and apply paragraph styles. ◊ Create and apply character styles. ◊ Nest Character styles inside paragraph styles. ◊ Create and apply object styles. ◊ Create and apply table styles. ◊ Globally update paragraph, character, object, cell and table styles. Globally update paragraph, character, object, cell and table styles. (this is duplicated on purposed!) ◊ Import and apply styles from other InDesign documents. ◊ Create styles groups. Macaroon wypas icing donut tootsie roll chupa chups gummies. Brownie halvah chupa chups chocolate cake marzipan. Topping macaroon dessert cheesecake dragée icing. Fruitcake lollipop danish bear claw tootsie roll candy canes croissant. Topping jujubes danish marzipan. Brownie danish toffee soufflé. Tiramisu powder li- quorice cheesecake applicake macaroon wypas tart. Chocolate cake pie applicake. Lemon drops donut cotton candy lemon drops. Cheesecake ice cream dragée sugar plum cheesecake lemon drops. Jelly-o fruitcake oat cake biscuit. Dragée pud- ding jelly-o cookie powder chocolate bar faworki chocolate bar. Macaroon oat cake sweet roll lemon drops. Pie cheesecake faworki ice cream jelly. Cheesecake cupcake danish cotton candy topping bonbon. Candy jelly topping pudding marshmallow sweet roll donut jelly topping. Cheesecake pastry faworki carrot cake icing icing marzipan. Topping wafer jelly beans croissant ice cream fruitcake lollipop. Dragée lemon drops oat cake brownie. Biscuit croissant marzipan. Sesame snaps cheesecake faworki marzipan jujubes croissant gingerbread marshmal- low candy. Caramels jelly-o chocolate. Croissant carrot cake cheesecake danish caramels jelly-o. Chocolate halvah gingerbread. Candy sesame snaps toffee toffee wafer sesame snaps danish. -

Pikestaff 26

Pikestaff 26 Plain Language Commission newsletter no. 26, April 2009 Plain Language Commission news New articles on clear writing and speaking Our research director, Martin Cutts, is writing a series of 3 articles for The Ombudsman, the newsletter of the British and Irish Ombudsman Association (BIOA). In the first – now on the Articles page of our website (www.clearest.co.uk/files/LongSentencesMeanHardLabour.pdf) – Martin offers tips on writing clearer letters, in particular keeping sentences short. Though the articles relate to Ombudsman work, they’re relevant to many kinds of public writing. In another article published on the website of the Improvement and Development Agency (IDeA), our associate Sarah Carr looks at the art of plain speaking and asks: ‘You may be used to writing in plain English, but can you speak plainly too? If not, you risk confusing or boring your listeners.’ Read the full article, which draws on examples from the Romans to modern politicians – including Barack Obama – not to mention Jack Sparrow, star of Pirates of the Caribbean, on our website or at http://www.idea.gov.uk /idk/core/page.do?pageId=9534169. Plain-language wizards to confabulate in Oz Australia’s Plain English Foundation is hosting the seventh 2-yearly conference of the Plain Language Association InterNational (PLAIN) from 15–17 October 2009. Aimed at government, industry and plain-language practitioners from Australia and around the world, the conference will focus on how plain language is improving services and saving money in government, industry, the law, medicine, engineering and finance. The conference title – Raising the Standard – reflects the ongoing work of the International Plain Language Working Group, which is looking at plain- language standards, the development of a plain-language institute, and accreditation and training for plain-language practitioners. -

Editor's Comment

July 2010 www.warrington-worldwide.co.uk 1 2 www.warrington-worldwide.co.uk July 2010 Editor Gary Skentelbery Production Paul Walker Editor’s Comment Advertising IS Warrington town centre the place to build a new £6 million James Balme ‘world class’ youth centre during these tough economic times? Tony Record Members of the borough council's No doubt their parents - particularly Freephone executive board think so - and believe those who live in the outer areas of the whole character of the town centre 0800 955 5247 the concept to be "exciting". borough - would have similar sufQciently to make it a suitable place Editorial Fifty four per cent of young people concerns. for our young people up to 10pm. 01925 623631 consulted say their ideal youth We are all in favour of Warrington We also mustn’t forget that provision would be located in the having a world-class youth facility but Email Warrington already has an excellent town centre and 76 per cent say they we would have thought the town youth facility based at the info@warrington- would use a town centre youth centre, with its unfortunate reputation, worldwide.co.uk provision if one existed. was the last place it should be internationally renowed Peace Centre, Many businesses and voluntary located. which is already home to Warrington Websites Youth club and the Warrington www.culchethlife.com groups are also enthusiastic and want It will be two or three years before to be involved - apparently even to the Foundation4Peace charity, as well as www.frodshamlife.co.uk the "Youth Zone" is likely to be built. -

The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy : Which Far Exceeds Any Thing

A 4 * R T O F o O K E R % Made P L A I N and EASY} Which fey exceeds any Thing of the Kind ever yet Publifhed* HI «. ■ s. CONTAINING, I Of Roafling, Boiling, bfc* XIII. To Pot and Make Hams, &c. II. Of Made-Diihes. XIV. Of Pickling. III. Read this Chaptef^and you will find how XV. Of Making Cakes, &c. Exptnftve a French Cook’s Sauce is. XVI. Of Chcefecakes, Creams, Jellies, Whip IV. To make a Number of pretty little Diflies Jit., Syllabubs, &c. for Suppei, or Side Difh, and little Corner- XVII. Of Made Wines, Bfewing, French Bread, Dilyes Jo r a great Table j and the reft you have Muffins, ISc. p in 'tfleChapteJ V Lent. XVIII. Jarring Cherries, and Preferves, &c. -f V. To dreft Fifh. XIX. To Makie Anchovies, Vermicella, Ketchup, VI. Of Soops and Broths-* Vinegar, and to keep Artichokes, French- VII. Of Puddings. Beans, &c. ' — » VIII. Of Pies. XX. Of Diftilling. IX. For a Faft-Dinner, a Number of good Diflies, XXI. How to Market, and the Seafons of the which you may make ufe for a Table at any Year for Butcher’s Meat, Poultry, Fifh, Herbs, other Time. Roots, &c. and Fruit. X- Directions for the Sick, XXII. A certain Cure for the Bite of a Mad Dog,. XI. For Captains of Ships. By Dr. Mead. XII. Of Hog’s Puddings, Saufages, &c. -a 4=4. LONDON: k Printed for- the Author ; and fb?d at Mrs. /Ijhburn's, a China-Shop, the Corner of Fleet-Ditch. -

PDF Download Sunny Days and Moon Cakes Ebook, Epub

SUNNY DAYS AND MOON CAKES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sarah Webb | 192 pages | 12 Oct 2015 | Walker Books Ltd | 9781406348361 | English | London, United Kingdom Sunny Days and Moon Cakes PDF Book I don't think the market is looking at environmental concerns. Ask Amy Green. The high prices commanded by the most prestigious mooncakes have crept even higher in the last year as food prices in China rose across the board. Other Editions. Small Gifts. Sure everyone has their own battle but just because someone is being all silent about it doesn't make it less hard. About 10 days from now, Lu will start to get calls from his regular customers, clamoring for him to collect mooncake boxes along with their newspapers, cardboard and other usual items. This review has been hidden because it contains spoilers. Pondering over taking a relaxing workcation? From coronasura Corona Demon to the migrant mother to lockdown, these are Kick off October with mooncakes, lanterns, and skygazing. And yes, be kind to all! I would read it again as it was a half- decent book, but I wouldn't as there are better books to read and where's the fun in reading something twice?! Average rating 4. Want to Read saving…. But what was a mooncake, I wondered? Writing for Children - Tips. Dec 07, Sally Flint rated it it was ok Shelves: childeren-s-literature. Melissa rated it really liked it Aug 16, Nowadays, the mooncake has become the Christmas fruitcake of China, passed around and regifted ad infinitum. Grace rated it it was amazing Jul 13, Three years after my first Qingming, only seven villagers made the journey up the mountain to the cemetery.