Countering Violent Extremism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cnn Debate Live Stream

Cnn debate live stream Continue Cutting cable is not too difficult if you are watching sports, in which case it is a nightmare. Huh989 over at Hackerspace wants to know: how do you stream sports, and sports packages are there worth it? Cable TV is insanely expensive, and with all the cheapest video services out there, it's easy to cut... MorePhoto Ed Yourdon.I have two things that, until recently, combined to reduce the quality of my life. These two things More Today is the final Republican debate before Super Tuesday-day a whopping twelve states and one U.S. territory will have either a primary or caucus. That's how to stream it online without cable. Before the general election, each state has its own primaries and caucuses, and today's Iowa caucuses ... Read more in the debate of the other five Republican presidential candidates: Ben Carson, Marco Rubio, Donald Trump, Ted Cruz and John Kasich. This is the last debate for Super Tuesday next week. On Tuesday, March 1, twelve states (Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Colorado, Georgia, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont and Virginia) and one U.S. territory (American Samoa) will hold either primary or caucuses. If you live in any of these areas, this is your last chance to watch the debate before it's time to help choose your candidate. The debate begins at 8:30 p.m. ET / 5:30 p.m. PT. Here's how you can stream it online: If you're a satellite radio subscriber, you can listen on SiriusXM Channel 115. -

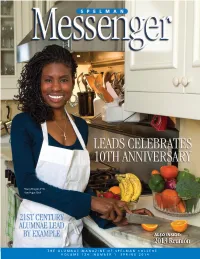

SPRING 2014 SPELMAN Messenger

Stacey Dougan, C’98, Raw Vegan Chef ALSO INSIDE: 2013 Reunion THE ALUMNAE MAGAZINE OF SPELMAN COLLEGE VOLUME 124 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2014 SPELMAN Messenger EDITOR All submissions should be sent to: Jo Moore Stewart Spelman Messenger Office of Alumnae Affairs ASSOCIATE EDITOR 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., Box 304 Joyce Davis Atlanta, GA 30314 COPY EDITOR OR Janet M. Barstow [email protected] Submission Deadlines: GRAPHIC DESIGNER Garon Hart Spring Semester: January 1 – May 31 Fall Semester: June 1 – December 31 ALUMNAE DATA MANAGER ALUMNAE NOTES Alyson Dorsey, C’2002 Alumnae Notes is dedicated to the following: EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE • Education Eloise A. Alexis, C’86 • Personal (birth of a child or marriage) Tomika DePriest, C’89 • Professional Kassandra Kimbriel Jolley Please include the date of the event in your Sharon E. Owens, C’76 submission. TAKE NOTE! WRITERS S.A. Reid Take Note! is dedicated to the following Lorraine Robertson alumnae achievements: TaRessa Stovall • Published Angela Brown Terrell • Appearing in films, television or on stage • Special awards, recognition and appointments PHOTOGRAPHERS Please include the date of the event in your J.D. Scott submission. Spelman Archives Julie Yarbrough, C’91 BOOK NOTES Book Notes is dedicated to alumnae authors. Please submit review copies. The Spelman Messenger is published twice a year IN MEMORIAM by Spelman College, 350 Spelman Lane, S.W., We honor our Spelman sisters. If you receive Atlanta, Georgia 30314-4399, free of charge notice of the death of a Spelman sister, please for alumnae, donors, trustees and friends of contact the Office of Alumnae Affairs at the College. -

Beyond the Bully Pulpit: Presidential Speech in the Courts

SHAW.TOPRINTER (DO NOT DELETE) 11/15/2017 3:32 AM Beyond the Bully Pulpit: Presidential Speech in the Courts Katherine Shaw* Abstract The President’s words play a unique role in American public life. No other figure speaks with the reach, range, or authority of the President. The President speaks to the entire population, about the full range of domestic and international issues we collectively confront, and on behalf of the country to the rest of the world. Speech is also a key tool of presidential governance: For at least a century, Presidents have used the bully pulpit to augment their existing constitutional and statutory authorities. But what sort of impact, if any, should presidential speech have in court, if that speech is plausibly related to the subject matter of a pending case? Curiously, neither judges nor scholars have grappled with that question in any sustained way, though citations to presidential speech appear with some frequency in judicial opinions. Some of the time, these citations are no more than passing references. Other times, presidential statements play a significant role in judicial assessments of the meaning, lawfulness, or constitutionality of either legislation or executive action. This Article is the first systematic examination of presidential speech in the courts. Drawing on a number of cases in both the Supreme Court and the lower federal courts, I first identify the primary modes of judicial reliance on presidential speech. I next ask what light the law of evidence, principles of deference, and internal executive branch dynamics can shed on judicial treatment of presidential speech. -

Extremists on the Left and Right Use Angry, Negative Language

PSPXXX10.1177/0146167218809705Personality and Social Psychology BulletinFrimer et al. 809705research-article2018 Empirical Research Paper Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin Extremists on the Left and Right 1 –16 © 2018 by the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc Use Angry, Negative Language Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218809705 10.1177/0146167218809705 journals.sagepub.com/home/pspb Jeremy A. Frimer1 , Mark J. Brandt2 , Zachary Melton3, and Matt Motyl3 Abstract We propose that political extremists use more negative language than moderates. Previous research found that conservatives report feeling happier than liberals and yet liberals “display greater happiness” in their language than do conservatives. However, some of the previous studies relied on questionable measures of political orientation and affective language, and no studies have examined whether political orientation and affective language are nonlinearly related. Revisiting the same contexts (Twitter, U.S. Congress), and adding three new ones (political organizations, news media, crowdsourced Americans), we found that the language of liberal and conservative extremists was more negative and angry in its emotional tone than that of moderates. Contrary to previous research, we found that liberal extremists’ language was more negative than that of conservative extremists. Additional analyses supported the explanation that extremists feel threatened by the activities of political rivals, and their angry, negative language represents efforts to communicate as much to others. Keywords language, anger, extremism, liberals and conservatives, threat, happiness Received February 27, 2018; revision accepted October 1, 2018 For too many of our citizens, a different reality exists: extremists—on both the political left and right—use more Mothers and children trapped in poverty in our inner cities; negative language than moderates. -

Commonwealth Lawyers Association Amicus

Nos. 15-1358, 15-1359, and 15-1363 In the Supreme Court of the United States JAMES W. ZIGLAR, Petitioner, v. AHMER IQBAL ABBASI, ET AL., Respondents. On Writs Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Second Circuit BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE COMMONWEALTH LAWYERS ASSOCIATION IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS GARY A. ISAAC Counsel of Record LOGAN A. STEINER JED W. GLICKSTEIN Mayer Brown LLP 71 S. Wacker Dr. Chicago, IL 60606 [email protected] (312) 782-0600 Counsel for Amicus Curiae (Additional Captions Listed on Inside Cover) JOHN D. ASHCROFT, ET AL., Petitioners, v. AHMER IQBAL ABBASI, ET AL., Respondents. DENNIS HASTY, ET AL., Petitioners, v. AHMER IQBAL ABBASI, ET AL., Respondents. i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES...................................... ii INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE...................1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT...........................2 ARGUMENT ..............................................................4 I. The Court Should Consider The Prac- tices Of Other Western Democracies And The European Court Of Human Rights In Deciding Whether To Recog- nize A Bivens Remedy .....................................4 II. Barring Any Remedy In This Case Would Be At Odds With Foreign Deci- sions And Practice ...........................................8 A. Other Nations Provide Monetary Remedies For Human-Rights Abuses In Alleged Terrorism- Related Cases........................................9 B. The European Court Of Human Rights Likewise Provides Mone- tary Remedies For Human Rights Violations In Cases Implicating National Security................................15 C. Other Western Democracies And The European Court Of Human Rights Recognize Damages Ac- tions Even Where National Secu- rity Is Implicated ................................19 CONCLUSION .........................................................20 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) Cases Agiza v. Sweden, Commc’n No. -

The Civilian Impact of Drone Strikes

THE CIVILIAN IMPACT OF DRONES: UNEXAMINED COSTS, UNANSWERED QUESTIONS Acknowledgements This report is the product of a collaboration between the Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School and the Center for Civilians in Conflict. At the Columbia Human Rights Clinic, research and authorship includes: Naureen Shah, Acting Director of the Human Rights Clinic and Associate Director of the Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School, Rashmi Chopra, J.D. ‘13, Janine Morna, J.D. ‘12, Chantal Grut, L.L.M. ‘12, Emily Howie, L.L.M. ‘12, Daniel Mule, J.D. ‘13, Zoe Hutchinson, L.L.M. ‘12, Max Abbott, J.D. ‘12. Sarah Holewinski, Executive Director of Center for Civilians in Conflict, led staff from the Center in conceptualization of the report, and additional research and writing, including with Golzar Kheiltash, Erin Osterhaus and Lara Berlin. The report was designed by Marla Keenan of Center for Civilians in Conflict. Liz Lucas of Center for Civilians in Conflict led media outreach with Greta Moseson, pro- gram coordinator at the Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School. The Columbia Human Rights Clinic and the Columbia Human Rights Institute are grateful to the Open Society Foundations and Bullitt Foundation for their financial support of the Institute’s Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, and to Columbia Law School for its ongoing support. Copyright © 2012 Center for Civilians in Conflict (formerly CIVIC) and Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America. Copies of this report are available for download at: www.civiliansinconflict.org Cover: Shakeel Khan lost his home and members of his family to a drone missile in 2010. -

CVE and Constitutionality in the Twin Cities: How Countering Violent Extremism Threatens the Equal Protection Rights of American Muslims in Minneapolis-St

American University Law Review Volume 69 Issue 6 Article 6 2020 CVE and Constitutionality in the Twin Cities: How Countering Violent Extremism Threatens the Equal Protection Rights of American Muslims in Minneapolis-St. Paul Sarah Chaney Reichenbach American University Washington College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Law and Society Commons, President/Executive Department Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Reichenbach, Sarah Chaney (2020) "CVE and Constitutionality in the Twin Cities: How Countering Violent Extremism Threatens the Equal Protection Rights of American Muslims in Minneapolis-St. Paul," American University Law Review: Vol. 69 : Iss. 6 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr/vol69/iss6/6 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CVE and Constitutionality in the Twin Cities: How Countering Violent Extremism Threatens the Equal Protection Rights of American Muslims in Minneapolis-St. Paul Abstract In 2011, President Barack Obama announced a national strategy for countering violent extremism (CVE) to attempt to prevent the “radicalization” of potential violent extremists. The Obama Administration intended the strategy to employ a community-based approach, bringing together the government, law enforcement, and local communities for CVE efforts. -

The Identification of Radicals in the British Parliament

1 HANSEN 0001 040227 名城論叢 2004年3月 31 THE IDENTIFICATION OF ‘RADICALS’ IN THE BRITISH PARLIAMENT, 1906-1914 P.HANSEN INTRODUCTION This article aims to identify the existence of a little known group of minority opinion in British society during the Edwardian Age. It is an attempt to define who the British Radicals were in the parliaments during the years immediately preceding the Great War. Though some were particularly interested in the foreign policy matters of the time,it must be borne in mind that most confined their energies to promoting the Liberal campaign for domestic welfare issues. Those considered or contemporaneously labelled as ‘Radicals’held ‘leftwing’views, being politically somewhat just left of centre. They were not revolutionaries or communists. They wanted change through reforms carried out in a democratic manner. Their failure to carry out changes on a significant scale was a major reason for the decline of the Liberals,and the rise and ultimate success of the Labour Party. Indeed, following the First World War, many Radicals defected from the Liberal Party to join Labour. With regard to historiography,it can be stated that the activities of British Radicals from the turn of the century to the outbreak of the First World War were the subject of interest to the most famous British historian of the second half of the 20century, A. J. P. Taylor. He wrote of them in his work The Troublemakers based on his Ford Lectures of 1956. By the early 1970s’A.J.A.Morris had established a reputation in the field with his book Radicalism Against War, 1906-1914 (1972),and a further publication of which he was editor,Edwardian Radical- ism 1900-1914 (1974). -

Tempered Radicals and Servant Leaders: Portraits of Spirited Leadership Amongst African Women Leaders

TEMPERED RADICALS AND SERVANT LEADERS: PORTRAITS OF SPIRITED LEADERSHIP AMONGST AFRICAN WOMEN LEADERS Faith Wambura Ngunjiri A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION May 2006 Committee: Judy A. Alston, Advisor Laura B. Lengel Graduate Faculty Representative Mark A. Earley Khaula Murtadha © 2006 Faith Wambura Ngunjiri All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Judy A. Alston, Advisor There have been few studies on experiences of African women in leadership. In this study, I aimed at contributing to bridging that literature gap by adding the voices of African women leaders who live and work in or near Nairobi Kenya in East Africa. The purpose of this study was to explore, explain and seek to understand women’s leadership through the lived experiences of sixteen women leaders from Africa. The study was an exploration of how these women leaders navigated the intersecting oppressive forces emanating from gender, culture, religion, social norm stereotypes, race, marital status and age as they attempted to lead for social justice. The central biographical methodology utilized for this study was portraiture, with the express aim of celebrating and learning from the resiliency and strength of the women leaders in the face of adversities and challenges to their authority as leaders. Leadership is influence and a process of meaning making amongst people to engender commitment to common goals, expressed in a community of practice. I presented short herstories of eleven of the women leaders, and in depth portraits of the other five who best illustrated and expanded the a priori conceptual framework. -

Blog Title Blog URL Blog Owner Blog Category Technorati Rank

Technorati Bloglines BlogPulse Wikio SEOmoz’s Blog Title Blog URL Blog Owner Blog Category Rank Rank Rank Rank Trifecta Blog Score Engadget http://www.engadget.com Time Warner Inc. Technology/Gadgets 4 3 6 2 78 19.23 Boing Boing http://www.boingboing.net Happy Mutants LLC Technology/Marketing 5 6 15 4 89 33.71 TechCrunch http://www.techcrunch.com TechCrunch Inc. Technology/News 2 27 2 1 76 42.11 Lifehacker http://lifehacker.com Gawker Media Technology/Gadgets 6 21 9 7 78 55.13 Official Google Blog http://googleblog.blogspot.com Google Inc. Technology/Corporate 14 10 3 38 94 69.15 Gizmodo http://www.gizmodo.com/ Gawker Media Technology/News 3 79 4 3 65 136.92 ReadWriteWeb http://www.readwriteweb.com RWW Network Technology/Marketing 9 56 21 5 64 142.19 Mashable http://mashable.com Mashable Inc. Technology/Marketing 10 65 36 6 73 160.27 Daily Kos http://dailykos.com/ Kos Media, LLC Politics 12 59 8 24 63 163.49 NYTimes: The Caucus http://thecaucus.blogs.nytimes.com The New York Times Company Politics 27 >100 31 8 93 179.57 Kotaku http://kotaku.com Gawker Media Technology/Video Games 19 >100 19 28 77 216.88 Smashing Magazine http://www.smashingmagazine.com Smashing Magazine Technology/Web Production 11 >100 40 18 60 283.33 Seth Godin's Blog http://sethgodin.typepad.com Seth Godin Technology/Marketing 15 68 >100 29 75 284 Gawker http://www.gawker.com/ Gawker Media Entertainment News 16 >100 >100 15 81 287.65 Crooks and Liars http://www.crooksandliars.com John Amato Politics 49 >100 33 22 67 305.97 TMZ http://www.tmz.com Time Warner Inc. -

2003 Iraq War: Intelligence Or Political Failure?

2003 IRAQ WAR: INTELLIGENCE OR POLITICAL FAILURE? A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By Dione Brunson, B.A. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. April, 2011 DISCLAIMER THE VIEWS EXPRESSED IN THIS ACADEMIC RESEARCH PAPER ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR AND DO NOT REFLECT THE OFFICIAL POLICIES OR POSITIONS OF THE U.S. GOVERNMENT, DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE, OR THE U.S. INTELLIGENCE COMMUNITY. ALL INFORMATION AND SOURCES FOR THIS PAPER WERE DRAWN FROM OPEN SOURCE MATERIALS. ii 2003 IRAQ WAR: INTELLIGENCE OR POLITICAL FAILURE? Dione Brunson, B.A. MALS Mentor: Ralph Nurnberger, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The bold U.S. decision to invade Iraq in 2003 was anchored in intelligence justifications that would later challenge U.S. credibility. Policymakers exhibited unusual bureaucratic and public dependencies on intelligence analysis, so much so that efforts were made to create supporting information. To better understand the amplification of intelligence, the use of data to justify invading Iraq will be explored alongside events leading up to the U.S.-led invasion in 2003. This paper will examine the use of intelligence to invade Iraq as well as broader implications for politicization. It will not examine the justness or ethics of going to war with Iraq but, conclude with the implications of abusing intelligence. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you God for continued wisdom. Thank you Dr. Nurnberger for your patience. iv DEDICATION This work is dedicated to Mom and Dad for their continued support. -

Facebook and Violent Extremism Awareness Brief

Facebook and Violent Extremism Understanding Facebook legitimate reasons, violent extremists, gangs, and terrorist groups also have a significant With more than 1 billion users, Facebook is presence and following on Facebook.1 The one of the most popular social networking following identifies the ways domestic and sites. After users create a personal profile or international extremists of all persuasions use organization page and add photos, contact Facebook to promote violence: information, and additional information, they can search for people with similar interests, Recruitment create networks of “friends,” communicate by sending private messages or posting Facebook provides violent extremists with a comments on another user’s wall, “like” pages vast recruiting ground. In the United States of organizations and join “groups” with other alone, 67 percent of all Internet users have a users who share similar interests, and post and Facebook profile, and the percentages are even share content created on Facebook or linked to higher for youth and young adults. Moreover, another website. Facebook is one of the top three websites visited by people under the age of 18.2 How Extremists Use Facebook Extremists take advantage of the fact that parents and law enforcement often are not Although individuals and organizations aware of the dangers that could be present worldwide use Facebook for a variety of when a young person spends large amounts AWARENESS BRIEF 2 AWARENESS BRIEF of time on Facebook. Extremist individuals bring propaganda to a wider audience and and organizations use this viewing potential to serve as a gateway to other extremist websites create lines of communication, enabling them where more radical content is available.