Incontinence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Anatomy of the Rectum and Anal Canal

BASIC SCIENCE identify the rectosigmoid junction with confidence at operation. The anatomy of the rectum The rectosigmoid junction usually lies approximately 6 cm below the level of the sacral promontory. Approached from the distal and anal canal end, however, as when performing a rigid or flexible sigmoid- oscopy, the rectosigmoid junction is seen to be 14e18 cm from Vishy Mahadevan the anal verge, and 18 cm is usually taken as the measurement for audit purposes. The rectum in the adult measures 10e14 cm in length. Abstract Diseases of the rectum and anal canal, both benign and malignant, Relationship of the peritoneum to the rectum account for a very large part of colorectal surgical practice in the UK. Unlike the transverse colon and sigmoid colon, the rectum lacks This article emphasizes the surgically-relevant aspects of the anatomy a mesentery (Figure 1). The posterior aspect of the rectum is thus of the rectum and anal canal. entirely free of a peritoneal covering. In this respect the rectum resembles the ascending and descending segments of the colon, Keywords Anal cushions; inferior hypogastric plexus; internal and and all of these segments may be therefore be spoken of as external anal sphincters; lymphatic drainage of rectum and anal canal; retroperitoneal. The precise relationship of the peritoneum to the mesorectum; perineum; rectal blood supply rectum is as follows: the upper third of the rectum is covered by peritoneum on its anterior and lateral surfaces; the middle third of the rectum is covered by peritoneum only on its anterior 1 The rectum is the direct continuation of the sigmoid colon and surface while the lower third of the rectum is below the level of commences in front of the body of the third sacral vertebra. -

Rectum & Anal Canal

Rectum & Anal canal Dr Brijendra Singh Prof & Head Anatomy AIIMS Rishikesh 27/04/2019 EMBRYOLOGICAL basis – Nerve Supply of GUT •Origin: Foregut (endoderm) •Nerve supply: (Autonomic): Sympathetic Greater Splanchnic T5-T9 + Vagus – Coeliac trunk T12 •Origin: Midgut (endoderm) •Nerve supply: (Autonomic): Sympathetic Lesser Splanchnic T10 T11 + Vagus – Sup Mesenteric artery L1 •Origin: Hindgut (endoderm) •Nerve supply: (Autonomic): Sympathetic Least Splanchnic T12 L1 + Hypogastric S2S3S4 – Inferior Mesenteric Artery L3 •Origin :lower 1/3 of anal canal – ectoderm •Nerve Supply: Somatic (inferior rectal Nerves) Rectum •Straight – quadrupeds •Curved anteriorly – puborectalis levator ani •Part of large intestine – continuation of sigmoid colon , but lacks Mesentery , taeniae coli , sacculations & haustrations & appendices epiploicae. •Starts – S3 anorectal junction – ant to tip of coccyx – apex of prostate •12 cms – 5 inches - transverse slit •Ampulla – lower part Development •Mucosa above Houstons 3rd valve endoderm pre allantoic part of hind gut. •Mucosa below Houstons 3rd valve upto anal valves – endoderm from dorsal part of endodermal cloaca. •Musculature of rectum is derived from splanchnic mesoderm surrounding cloaca. •Proctodeum the surface ectoderm – muco- cutaneous junction. •Anal membrane disappears – and rectum communicates outside through anal canal. Location & peritoneal relations of Rectum S3 1 inch infront of coccyx Rectum • Beginning: continuation of sigmoid colon at S3. • Termination: continues as anal canal, • one inch below -

48 Anal Canal

Anal Canal The rectum is a relatively straight continuation of the colon about 12 cm in length. Three internal transverse rectal valves (of Houston) occur in the distal rectum. Infoldings of the submucosa and the inner circular layer of the muscularis externa form these permanent sickle- shaped structures. The valves function in the separation of flatus from the developing fecal mass. The mucosa of the first part of the rectum is similar to that of the colon except that the intestinal glands are slightly longer and the lining epithelium is composed primarily of goblet cells. The distal 2 to 3 cm of the rectum forms the anal canal, which ends at the anus. Immediately proximal to the pectinate line, the intestinal glands become shorter and then disappear. At the pectinate line, the simple columnar intestinal epithelium makes an abrupt transition to noncornified stratified squamous epithelium. After a short transition, the noncornified stratified squamous epithelium becomes continuous with the keratinized stratified squamous epithelium of the skin at the level of the external anal sphincter. Beneath the epithelium of this region are simple tubular apocrine sweat glands, the circumanal glands. Proximal to the pectinate line, the mucosa of the anal canal forms large longitudinal folds called rectal columns (of Morgagni). The distal ends of the rectal columns are united by transverse mucosal folds, the anal valves. The recess above each valve forms a small anal sinus. It is at the level of the anal valves that the muscularis mucosae becomes discontinuous and then disappears. The submucosa of the anal canal contains numerous veins that form a large hemorrhoidal plexus. -

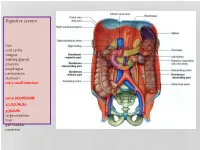

The Digestive System Overview of the Digestive System • Organs Are Divided Into Two Groups the Alimentary Canal and Accessory

C H A P T E R 23 The Digestive System 1 Overview of the Digestive System • Organs are divided into two groups • The alimentary canal • Mouth, pharynx, and esophagus • Stomach, small intestine, and large intestine (colon) • Accessory digestive organs • Teeth and tongue • Gallbladder, salivary glands, liver, and pancreas 2 The Alimentary Canal and Accessory Digestive Organs Mouth (oral cavity) Parotid gland Tongue Sublingual gland Salivary glands Submandibular gland Esophagus Pharynx Stomach Pancreas (Spleen) Liver Gallbladder Transverse colon Duodenum Descending colon Small intestine Jejunum Ascending colon Ileum Cecum Large intestine Sigmoid colon Rectum Anus Vermiform appendix Anal canal Figure 23.1 3 1 Digestive Processes • Ingestion • Propulsion • Mechanical digestion • Chemical digestion • Absorption • Defecation 4 Peristalsis • Major means of propulsion • Adjacent segments of the alimentary canal relax and contract Figure 23.3a 5 Segmentation • Rhythmic local contractions of the intestine • Mixes food with digestive juices Figure 23.3b 6 2 The Peritoneal Cavity and Peritoneum • Peritoneum – a serous membrane • Visceral peritoneum – surrounds digestive organs • Parietal peritoneum – lines the body wall • Peritoneal cavity – a slit-like potential space Falciform Anterior Visceral ligament peritoneum Liver Peritoneal cavity (with serous fluid) Stomach Parietal peritoneum Kidney (retroperitoneal) Wall of Posterior body trunk Figure 23.5 7 Mesenteries • Lesser omentum attaches to lesser curvature of stomach Liver Gallbladder Lesser omentum -

Part Innervation Blood Supply Venous Drainage

sheet PART INNERVATION BLOOD SUPPLY VENOUS DRAINAGE LYMPH DRAINAGE Roof: greater palatine & nasopalatine Mouth nerves (maxillary N.) Floor: lingual nerve (mandibular N.) Taste {ant 1/3}: chorda tympani nerve (facial nerve) Cheeks: buccal nerve (mandibular N.) Buccinator muscle: Buccal Nerve 1 (facial Nerve) Orbicularis oris muscle: facial nerve Tip: Submental LNs Tongue lingual artery (ECA) sides of ant 2/3: Ant 1/3: Lingual nerve (sensory) & tonsillar branch of facial artery lingual veins correspond to submandibular & chorda tympani (Taste) (ECA) the arteries and drain into IJV deep cervical LNs Post 2/3: glossopharyngeal N. (both) ascending pharyngeal artery post 1/3: Deep (ECA) cervical LNs greater palatine vein greater palatine artrey Palate Hard Palate: greater palatine and (→maxillary V.) (maxillary A.) nasopalatine nerves ascending palatine vein Deep cervical lymph ascending palatine artrey Soft Palate: lesser palatine and (→facial V.) nodes (facial A.) glossopharyngeal nerves ascending pharyngeal ascending pharyngeal artery vein PANS (secreto-motor) & Sensory: 2 Parotid gland Auriculotemporal nerve {Inferior salivary Nucleus → tympanic branch of glossopharyngeal N.→ Lesser petrosal nerve parasympathetic preganglionic fibres → otic ganglia → auriculotemporal nerve parasympathetic postganglionic fibres} sheet PART INNERVATION BLOOD SUPPLY VENOUS DRAINAGE LYMPH DRAINAGE PANS (secreto-motor): facial nerve Submandibular Sensory: lingual nerve gland {Superior salivary Nucleus → Chorda tympani branch from facial -

Normal Gross and Histologic Features of the Gastrointestinal Tract

NORMAL GROSS AND HISTOLOGIC 1 FEATURES OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT THE NORMAL ESOPHAGUS left gastric, left phrenic, and left hepatic accessory arteries. Veins in the proximal and mid esopha- Anatomy gus drain into the systemic circulation, whereas Gross Anatomy. The adult esophagus is a the short gastric and left gastric veins of the muscular tube measuring approximately 25 cm portal system drain the distal esophagus. Linear and extending from the lower border of the cri- arrays of large caliber veins are unique to the distal coid cartilage to the gastroesophageal junction. esophagus and can be a helpful clue to the site of It lies posterior to the trachea and left atrium a biopsy when extensive cardiac-type mucosa is in the mediastinum but deviates slightly to the present near the gastroesophageal junction (4). left before descending to the diaphragm, where Lymphatic vessels are present in all layers of the it traverses the hiatus and enters the abdomen. esophagus. They drain to paratracheal and deep The subdiaphragmatic esophagus lies against cervical lymph nodes in the cervical esophagus, the posterior surface of the left hepatic lobe (1). bronchial and posterior mediastinal lymph nodes The International Classification of Diseases in the thoracic esophagus, and left gastric lymph and the American Joint Commission on Cancer nodes in the abdominal esophagus. divide the esophagus into upper, middle, and lower thirds, whereas endoscopists measure distance to points in the esophagus relative to the incisors (2). The esophagus begins 15 cm from the incisors and extends 40 cm from the incisors in the average adult (3). The upper and lower esophageal sphincters represent areas of increased resting tone but lack anatomic landmarks; they are located 15 to 18 cm from the incisors and slightly proximal to the gastroesophageal junction, respectively. -

Board Review for Anatomy

Board Review for Anatomy John A. McNulty, Ph.D. Spring, 2005 . LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO Stritch School of Medicine Key Skeletal landmarks • Head - mastoid process, angle of mandible, occipital protuberance • Neck – thyroid cartilage, cricoid cartilage • Thorax - jugular notch, sternal angle, xiphoid process, coracoid process, costal arch • Back - vertebra prominence, scapular spine (acromion), iliac crest • UE – epicondyles, styloid processes, carpal bones. • Pelvis – ant. sup. iliac spine, pubic tubercle • LE – head of fibula, malleoli, tarsal bones Key vertebral levels • C2 - angle of mandible • C4 - thyroid notch • C6 - cricoid cartilage - esophagus, trachea begin • C7 - vertebra prominence • T2 - jugular notch; scapular spine • T4/5 - sternal angle - rib 2 articulates, trachea divides • T9 - xiphisternum • L1/L2 - pancreas; spinal cord ends. • L4 - iliac crest; umbilicus; aorta divides • S1 - sacral promontory Upper limb nerve lesions Recall that any muscle that crosses a joint, acts on that joint. Also recall that muscles innervated by individual nerves within compartments tend to have similar actions. • Long thoracic n. - “winged” scapula. • Upper trunk (C5,C6) - Erb Duchenne - shoulder rotators, musculocutaneous • Lower trunk (C8, T1) - Klumpke’s - ulnar nerve (interossei muscle) • Radial nerve – (Saturday night palsy) - wrist drop • Median nerve (recurrent median) – thenar compartment - thumb • Ulnar nerve - interossei muscles. Lower limb nerve lesions Review actions of the various compartments. • Lumbosacral lesions - usually -

Digestive System

Digestive system Lips oral cavity tongue salivary glands pharynx esophagus peritoneum stomach m6-7 small intestine: cm25 DEODENUM: 2/5JEJUNUM: 3/5ILIUM: large intestine liver gall bladder pancreas :Duodenum Sup. Part Descending part Horizontal part Ascending part Major duodenal papilla Minor duodenal papilla : JEJUNUM / ILIUM From duodenojejunal curvature To Iliocecal Different jejunum & ilium 3Tenia coli: sigmoid 2 / rectum 0 Houstra / saccule Appendices epiploicae : No in Appendix / cecum / rectum Many in sigmoid DIFFERENT BETWEEN SMALL AND LARGE INTESTINE large intestine 1.5m Cecum appendix ascending colon transverse colon descending colon sigmoid colon rectum anal canal McBurneys point ascending colon transverse colon descending colon sigmoid colon :Rectum cm 12 Sacral flexure Puborectalis muscle Perineal flexure Rectum Ampulla : Anal canal cm 4 sup. = anal column / anal valve / anal sinus / pectinate line 2/3 Hiltons white line .inf 1/3 :Anal sphincter Internal sphincter External sphincter: deep / superficial / subcutaneous Liver: 1.5 kgr Located in Rt. & lf. Hypochondriac & epigastric region Surfaces: Sup. Anterior Surface: falciform ligament Inf. Surface: H shape fissure / porta hepatis / quadrate lobe / qudate lobe Post. Surface: bare area Rt. Surface: ribs 7-11 / Rt. lung Liver viewed from posterior Liver viewed from inferior Liver viewed from inferior Liver viewed from posterior :Liver vasculature 20%Hepatic artery 80%Portal vein Supra hepatic vein IVC :Nerve Sympathetic Parasympathetic From Vagus+ Phernic + celiac :Gall bladder Located in inf. Surface of liver cm7-10 Length: cm3-4 Wide: :Structure Fundus Body Infundibulum Neck Systic duct :Pancreas 2–L1 L cm15-20 Length: cm3Wide: cm2 Thickness: gram 90 :Structure Head :Uncinate process / sup. Mesenteric artery Neck: portal vein / sup. -

Anatomy of Anal Canal

Anatomy of Anal Canal Dr Garima Sehgal Associate Professor Department of Anatomy King George’s Medical University, UP, Lucknow DISCLAIMER: • The presentation includes images which are either hand drawn or have been taken from google images or books. • They are being used in the presentation only for educational purpose. • The author of the presentation claims no personal ownership over images taken from books or google images. • However, the hand drawn images are the creation of the author of the presentation Subdivisions of the perineum • Transverse line joining the anterior part of ischial tuberosities divides perineum into: 1. Urogenital region / triangle- ANTERIORLY 2. Anal region / triangle - POSTERIORLY Anal canal may be affected by many conditions that are not so rare, not necessarily serious and endangering to life but on the contrary very INCAPACITATING Haemorrhoids Anal fistula Anal fissure Perianal abscess Learning objectives At the end of this teaching session on anatomy of Anal canal all the MBBS 1st Year students must be able to correctly: • Describe the location, extent and dimensions of the anal canal • Enumerate the relations of the anal canal • Enumerate the subdivisions of anal canal • Describe & Diagrammatically display the special features on the interior of the anal canal • Discuss the importance of pectinate / dentate line • Write a short note on the arterial supply, venous drainage, nerve supply & lymphatic drainage • Write a short note on the sphincters of the anal canal • Describe the anatomical basis of internal -

Anatomy: Know Your Abdomen

Anatomy: Know Your Abdomen Glossary Abdomen - part of the body below the thorax (chest cavity); separated by the diaphragm. Anterior - towards the front of the body. For example, the umbilicus is anterior to the spine. Appendix - blind ended pouch. Autonomic nervous system – part of the nervous system responsible for functions we are not consciously aware of, such as heart rate and digestion. Aponeurosis – thin, flat fibrous sheath that replaces tendon for thin flat muscles. Bile - yellow/brown fluid produced and secreted by the liver and stored in the gallbladder. Aids digestion of lipids (fats). Conjoint tendon – the posterior wall of the inguinal canal directly behind the superficial inguinal ring formed by the union of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles. CT – computerised topography. A method of using x-rays to examine the internal structures by rotating the x-ray source around the body. Dorsal – this term relates to the ‘back’ of an organism. For humans this is similar to ‘posterior’ and is used more when describing embryological development. Distal – far from the centre of the body or point of attachment. For example, the wrist is distal to the elbow. Duodenum - the first part of the small intestine. It is continuous with the stomach and jejunum (second part of the small intestine), so food will pass from stomach to duodenum to jejunum. Duodenal papillae - small round elevations in the mucosa of the second part of the duodenum. There are two duodenal papillae, major and minor. The major papilla is also known as the ‘Papilla of Vater’. The major duodenal papilla is where the ampulla of Vater (joining of pancreatic duct and common bile duct) opens into the duodenum, allowing bile and enzymes to be delivered to facilitate digestion. -

Digestive System Part

Business Reminder: No class Monday (Memorial Day) Midterm 2 is Tuesday 5/28/13 Optional review session tomorrow @ 5pm Homework due in Lab 1. PreLab 8 (1pt) 2. Replace a Missing Assignment (4 pts) Homework page 17 Digestive System Part 2 Digestive System Small intestine Major organ of digestion and absorption 2 - 4 m long; from pyloric sphincter to ileocecal valve Subdivisions Duodenum Jejunum Ileum Digestive System Small intestine Structural modifications Villi Intestinal glands Mucosa Submucosa Parotid gland Mouth (oral cavity) Sublingual gland Salivary Tongue Submandibular glands gland Esophagus Pharynx Stomach Pancreas Liver (Spleen) Gallbladder Transverse colon Duodenum Descending colon Small Jejunum Ascending colon intestine Ileum Cecum Large Sigmoid colon intestine Rectum Vermiform appendix Anus Anal canal Figure 23.1 Vein carrying blood to hepatic portal vessel Muscle layers Lumen Circular folds Villi (a) Figure 23.22a Microvilli (brush border) Absorptive cells Lacteal Goblet cell Blood Vilus capillaries Mucosa associated lymphoid tissue Enteroendocrine Intestinal crypt cells Muscularis Venule mucosae Lymphatic vessel Duodenal gland Submucosa (b) Figure 23.22b Microvilli Absorptive cell (b) Figure 23.3b Digestive System Chemical digestion in the small intestine Food entering SI = partially digested Intestinal juice Water, mucous Crypt cells produce lysozyme Microvilli (brush border) Absorptive cells Lacteal Goblet cell Blood Villus capillaries Mucosa associated lymphoid tissue Enteroendocrine Intestinal crypt -

Diagnosis and Diagnostic Imaging of Anal Canal Cancer

Diagnosis and Diagnostic Imaging of Anal Canal Cancer a, b Kristen K. Ciombor, MD, MSCI *, Randy D. Ernst, MD , c Gina Brown, MBBS, MRCP, FRCR KEYWORDS Anal canal cancer Magnetic resonance imaging 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography Anoscopy Endoanal ultrasound KEY POINTS Anal canal cancer can present with rectal bleeding, pain, or change in bowel habits and is often a delayed diagnosis owing to the similarity of symptoms to common benign conditions. Staging procedures for anal canal cancer can include anoscopy, biopsy, computed tomography, MRI, endoanal ultrasound imaging, and/or 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-PET. Imaging modalities for detection, staging, evaluation of treatment response and surveil- lance of anal canal cancer are sensitive and robust. INTRODUCTION Anal canal cancer is a relatively uncommon malignancy, with an incidence of approx- imately 30,000 cases annually worldwide.1 Owing to the unique location and anatomy of this malignancy, careful examination and diagnostic procedures are necessary for optimal staging and treatment. This article focuses on the underlying anatomy of the anorectal region, important imaging characteristics of the anus, common clinical pre- sentations of anal canal cancer, and the diagnostic procedures required for adequate staging and treatment of this cancer type. Disclosure Statement: G. Brown is supported by the UK NIHR Biomedical Research Centre. a Division of Medical Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, The Ohio State University, A445A Starling Loving Hall, 320 West 10th Avenue, Columbus, OH 43210, USA; b Division of Diagnostic Imaging, Department of Diagnostic Radiology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Unit 1473, PO Box 301402, Houston, TX 77230-1402, USA; c Department of Radiology, The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and Imperial College London, Downs Road, Sutton, Surrey SM2 5PT, UK * Corresponding author.