A Taste of Text – Sukkot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

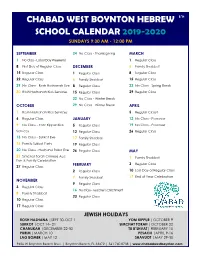

Chabad West Boynton Hebrew School Calendar 2019-2020

CHABAD WEST BOYNTON HEBREW B”H SCHOOL CALENDAR 2019-2020 SUNDAYS 9:30 AM - 12:00 PM SEPTEMBER 24 No Class - Thanksgiving MARCH 1 No Class - Labor Day Weekend 1 Regular Class 8 First Day of Regular Class DECEMBER 6 Family Shabbat 15 Regular Class 1 Regular Class 8 Regular Class 22 Regular Class 6 Family Shabbat 15 Regular Class 29 No Class - Rosh Hashanah Eve 8 Regular Class 22 No Class - Spring Break 30 Rosh Hashanah Kids Services 15 Regular Class 29 Regular Class 22 No Class - Winter Break OCTOBER 29 No Class - Winter Break APRIL 1 Rosh Hashanah Kids Services 5 Regular Class? 6 Regular Class JANUARY 12 No Class - Passover 9 No Class - Yom Kippur Kids 5 Regular Class 19 No Class - Passover Services 12 Regular Class 26 Regular Class 13 No Class - Sukkot Eve 17 Family Shabbat 16 Family Sukkot Party 19 Regular Class 20 No Class - Hoshana Raba Eve 26 Regular Class MAY 21 Simchat Torah Chinese Auc- 1 Family Shabbat tion & Family Celebration FEBRUARY 3 Regular Class 27 Regular Class 2 Regular Class 10 Last Day of Regular Class 7 Family Shabbat 17 End of Year Celebration NOVEMBER 9 Regular Class 3 Regular Class 16 No Class - Teacher’s Enrichment 8 Family Shabbat 23 Regular Class 10 Regular Class 17 Regular Class JEWISH HOLIDAYS ROSH HASHANA |SEPT 30-OCT 1 YOM KIPPUR |OCTOBER 9 SUKKOT |OCT 14– 21 SIMCHAT TORAH |OCTOBER 22 CHANUKAH |DECEMBER 22-30 TU B’SHVAT| FEBRUARY 10 PURIM |MARCH 10 PESACH |APRIL 9-16 LAG BOMER |MAY 12 SHAVUOT |MAY 29-30 9406 W Boynton Beach Blvd. -

Chabad Chodesh Sivan 5773 5773 Sivan Chodesh Chabad CONGREGATION LEVI YI

בס“ד Sivan 5773/2013 SPECIAL DAYS IN SIVAN Volume 23, Issue 3 Sivan 1/May 10/Friday Rosh Chodesh Sivan We don't say Tachnun the first twelve days of Sivan, because the first is Rosh Chodesh, followed by Yom HaMeyuchas, Sheloshes Yimei Hagbalah, Erev Shavuos, Isru Chag, and Sheva Yimei Tashlumin, the seven days allowed for bringing the Shavuos Korbanos. (Alter Rebbe's Sidur, Alter Rebbe's Shulchan Aruch 494:20) " . Obviously the main preparation for Matan Torah is through studying Torah. Particularly, the laws of the holiday, including and especially, those parts of Torah that explain the greatness of Matan Torah, through which is added the desire to receive the Torah. Whether in Nigleh, for instance, the Sugya of Matan Torah in Maseches Shabbos (86a) and Shnas Homosayim Shnas Maamarim about Matan Torah in Chasidus. – More specifically, from Rosh Chodesh on, to make sure everyone has the spiritual needs for learn the Maamar 'BaChodesh HaShelishi' in the holiday, especially the appropriate Torah Or, ParshasYisro. This Maamar is preparation for the holiday." (Sichah, Shabbos accessible to everyone, men, women, and Mevarchim Sivan, 5748) children, at their level. The Jewish People camped at Har Sinai as one As far as others, just as we need to make sure person, with one heart, 2448 [1313 BCE]. everyone has the physical needs of the holiday, (Shemos 19:1, Rashi) food and drink on a broad scale, so we must Shavuos Laws and Customs TZCHOK CHABAD OF HANCOCK PARKTuesday Night ~ Thursday / May 14-16 We don’t say Tachnun from the first of Sivan night, so that the forty-nine days of the through the twelfth: The first day is Rosh Omer will be complete. -

Shabbat Chol Hamoed Sukkot (Kohelet)

Weekly Newsletter Vol. XX, No. 14 Tishrei 19, 5776 – Tishrei 26 5776 October 2, 2015 – October 9, 2015 YIEB GUESTS Jay Weinstein, Rabbi SHABBAT CHOL HAMOED Please help us by welcoming all guests who are 732.354.5912 (cell) visiting YIEB each Shabbat and Yom Tov. In particular, 732.254.1860 x2 (office) SUKKOT (KOHELET) we expect that a YIEB guest joining us over Shmini Atzeret/Simchat Torah will be bringing a Guide Dog Bertin Lefkovic, Editor WELCOME TO YESHIVA UNIVERSITY TORAH with them. Please do not pet the dog. If you have any Jeff Chustckie, President TOURS! Thank you to Max Hoffman, questions, kindly be in touch with Rabbi Weinstein. Yaakov Wasser, Inaugural Rabbi Noam Lubofsky, David Izso, Erin Shama, and Thank you! (1979-2009), Retired Emily Okin for joining us for Yom Tov. ______________________________________________ The next newsletter deadline is Candle Lighting ..................................... 6:21PM YIEB CHESSED TRIP FOR HABITAT FOR HUMANITY TUESDAY, OCTOBER 6TH at 11:59PM Friday Mincha ...................................... 6:26PM Join Rabbi Weinstein for a YIEB Chesed Trip! Build a All submissions must be emailed to [email protected] home in Highland Park. Sunday, October 18th, Shkia ..................................................... 6:39PM OFFICE HOURS - MONDAY-FRIDAY 9AM-1PM 12:00-5:00 PM. Open to participants 16 or older. Evening hours are available on an appointment basis. Please e-mail Shabbat Shacharit ........................ 8:00, 9:00AM Limited space available. RSVP to [email protected] or call 732.254.1860x1 during regular Latest Sh’ma ......................................... 9:51AM office hours to schedule an appointment. [email protected] See Flyer for More Details KOHELET prior to Torah Reading ______________________________________________ THANK YOU Shabbat Mincha .................................. -

Jewish Center of Teaneck

Jewish Center of Teaneck 70 Sterling Place Daniel Fridman, Rabbi Teaneck, NJ 07666 Phone: 201-833-0515 OFFICERS Uri Horowitz, President www.jcot.org Dr. Benjamin Cooper, Vice President Allen Ezrapour, Treasurer Daniel Chazin, Secretary BOARD OF TRUSTEES Shmuel Elhadad Ginnine Fried Eva Lynn Gans Ephraim Love Dr. Steve Myers Bob Rabkin ** Rebecca Richmond Daniel Wetrin בס"ד PAST PRESIDENTS Edward Anfang* David N. Bilow April 17, 2020 Dr. Barnet Bookstaver* Henry Dubro Jules Edelman* Sen. Matthew Feldman* Dear Friend, Eva Lynn Gans David W. Goldman* Joseph Gottesman Leonard Gould* First and foremost, I want to thank all of you for your grace and resilience over Pesach. So Steven Morey Greenberg Sanford Hausler many of you commented to me regarding the unique meaning of this experience, even as it S.E. Melvin Hecht was singularly challenging as well. Chaya and I continue to think of each of you. Kurt J. Heilbronner* Seymour Herr* George H. Kaplan* Philip Kaplan* Table of Contents Martin H. Kornheiser Major L. Landau* Herman B. Levine* Merwin S. Levine* I. Community Updates Leonard Marcus* II. Drashah and Parsha Questions for Shabbat Shemini Murray Megibow* Milton Polevoy III. Shabbat Mevarchim Howard Reinert* Adolf Robison* IV. Pirkei Avot Sidney Roffman* Abbe Rosner V. Schedule for Erev Shabbat-Sunday Mark I. Schlesinger Abraham Schlussel VI. Purchasing Chametz after Pesach Fred Schneider* Dr. J. Dewey Schwarz* VII. Customs of Sefirat HaOmer- Recorded Music this Year Louis Stein* Herbert Stern Archie A. Struhl* I. Community Updates Isaac Student David S. Waldman Our thoughts continue to be with all of those afflicted with this virus, and their families, George Jack Wall* Dr. -

It's Not Too Late to Join the Kol Nidrei Appeal … Www

IN OUR COMMUNITY —————————–——–——————– Mazel Tov to our Simchas Torah Chassanim Chassan Torah: Rabbi Allen Schwartz Chassan Bereishis: Joel Goldman Chassan Maftir: Isaac Galena Mazel Tov Shira & David Wildman, on the birth and bris of WHAT’S HAPPENING AT OZ their son Liam Yishai Ronit and Aaron Etra on the birth of a boy CHOL HAMOED SUKKOT Friday September 28 (Tishrei 19) Synagogue Notice 6:00a Shacharit in Main Shul Catered Shabbos Meals are Sold-Out 6:30a Shacharit in Bet Medrash Downstairs Sukkah Hours: 9a-2p, 6p-10p 7:45a Shacharit in Main Shul 6:25p Candle Lighting Hoshana Rabba at OZ 6:35p Mincha/Maariv Please note there will 2 Shacharit Minyans will 7:30p Catered Meal SOLD-OUT meet in the Main Shul, 7:00a & 8:45a Shabbat, September 29 (Tishrei 20) Refuah Sheleimah 7:30a Hashkama Devorah Yocheved bat Chana Tziporah, Rina bat Gitel Tova, 8:30a Parsha Shiur Tsiporah bat Shprintza Rachel, Hene bat Rivkah Rachel, 9:15a Shacharit Sarah Leah bat Yocheved Rut, Leibish ben Tzipa, Mordechai SPONSORSHIPS 10:00a Youth Groups Lev ben Frieda Frumah, Avrohom Moshe ben Miriam 12:00p Catered Luncheon SOLD-OUT —————————–——–——————– Shaindel, Rivkah bat Basha, Noa Bat Sheila, Adi Ateret bat BYOSS — Bring Own Seudah Shlishit Ilana Miriam, Chaya bat Kalanit, Gad Meir ben Aviva Etya, 6:05p Mincha, followed by Shiur in Sukkah Shabbat Chol HaMoed Kiddushim & Shiurim Aaron Yaakov ben Miriam, Dovid Beryl ben Rhoda Rebecca Davis & Percy Deift, commemorating the by Yoni Zolty: vZos HaBracha Yahrzeit of Rebecca’s father Barnett Davis z’l 7:25p Maariv -

Advancedaudioblogs1#1 Top10israelitouristdestinations

LESSON NOTES Advanced Audio Blog S1 #1 Top 10 Israeli Tourist Destinations: The Dead Sea CONTENTS 2 Hebrew 2 English 3 Vocabulary 4 Sample Sentences 4 Cultural Insight # 1 COPYRIGHT © 2013 INNOVATIVE LANGUAGE LEARNING. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. HEBREW .1 . .2 4 0 0 - , . , . . . , .3 . . , 21 . . , . , , .4 . ; . 32-39 . . 20-32 , . ," .5 . , ENGLISH 1. The Dead Sea CONT'D OVER HEBR EW POD1 0 1 . C OM ADVANCED AUDIO BLOG S 1 #1 - TOP 10 IS RAELI TOURIS T DESTINATIONS: THE DEAD S EA 2 2. The miracle known as the Dead Sea has attracted thousands of people over the years. It is located near the southern area of the Jordan valley. The salt-rich Dead Sea is the lowest point on the earth's surface, being 400 meters below sea level. The air around the Dead Sea is unpolluted, dry, and pollen-free with low humidity, providing a naturally relaxing environment. The air in the region has a high mineral content due to the constant evaporation of the mineral rich water. 3. The Dead Sea comes in the list of the world's greatest landmarks, and is sometimes considered one of the Seven Wonders of the World. People usually miss out on this as they do not realize the importance of its unique contents. The Dead Sea has twenty-one minerals which have been found to give nourishment to the skin, stimulate the circulatory system, give a relaxed feeling, and treat disorders of the metabolism and rheumatism and associate pains. The Dead Sea mud has been used by people all over the world for beauty purposes. -

Calendar & Program Guide 5779

ב"ה JEWISH COMMUNITY Calendar & Program Guide 5779 2018-2019 Chabad of Palm Beach Gardens 6100 PGA BLVD, PBG, FL 33418 561.624.2223 | JEWISHGARDENS.COM Dear Friends, This Jewish Calendar and Program guide is Dedicated by We are delighted to present the 13th annual Jewish Community Calendar & ROBERT & MAUREEN BERGER IN GRATITUDE TO G-D ALMIGHTY Program Guide from Chabad of Palm Beach Gardens. FOR THE MANY BLESSINGS BESTOWED UPON THEM The Jewish Calendar with its fluctuating Jewish Festivals has always been important because it HOW TO LIGHT SHABBOS CANDLES connects us today with the traditions It starts with one light. You can add a candle for of our past. As Jews, few things are your soul mate, and if you are a mother, one for each more important to us than our child. A girl over the age of three may (with some heritage. help from Mom) light a candle of her own. Anti-Semites know this well, To honor the divine spiritual connection of lighting and that’s why you’ll notice that Shabbat candles, we recite a blessing just after oftentimes the first place that kindling our candles, which are lit 18 minutes they try to attack us is in our before sundown. cemeteries, trying to erase our connection to the memories of Once the candle(s) are lit, close your eyes, and our past. with your hands gently moving above the flames, motion the warmth towards your eyes three times. Then softly placing Almost every Jew we meet in your hands over your eyes, pronounce the words that women across the globe Palm Beach had a zeidy who have spoken aloud for thousands of years. -

Pesach for the Year 5780 Times Listed Are for Passaic, NJ Based in Part Upon the Guide Prepared by Rabbi Shmuel Lesches (Yeshivah Shul – Young Yeshivah, Melbourne)

בס״ד Laws and Customs: Pesach For the year 5780 Times listed are for Passaic, NJ Based in part upon the guide prepared by Rabbi Shmuel Lesches (Yeshivah Shul – Young Yeshivah, Melbourne) THIRTY DAYS BEFORE PESACH not to impact one’s Sefiras Haomer. CLEANING AWAY THE [Alert: Polar flight routes can be From Purim onward, one should learn CHAMETZ equally, if not more, problematic. and become fluent in the Halachos of Guidance should be sought from a It is improper to complain about the Pesach. Since an inspiring Pesach is Rav familiar with these matters.] work and effort required in preparing the product of diligent preparation, for Pesach. one should learn Maamarim which MONTH OF NISSAN focus on its inner dimension. Matzah One should remember to clean or Tachnun is not recited the entire is not eaten. However, until the end- discard any Chometz found in the month. Similarly, Av Harachamim and time for eating Chometz on Erev “less obvious” locations such as Tzidkasecha are omitted each Pesach, one may eat Matzah-like vacuum cleaners, brooms, mops, floor Shabbos. crackers which are really Chometz or ducts, kitchen walls, car interiors egg-Matzah. One may also eat Matzah The Nossi is recited each of the first (including rented cars), car-seats, balls or foods containing Matzah twelve days of Nissan, followed by the baby carriages, highchairs (the tray meal. One may also be lenient for Yehi Ratzon printed in the Siddur. It is should also be lined), briefcases, children below the age of Chinuch. recited even by a Kohen and Levi. -

KMS Sefer Minhagim

KMS Sefer Minhagim Kemp Mill Synagogue Silver Spring, Maryland Version 1.60 February 2017 KMS Sefer Minhagim Version 1.60 Table of Contents 1. NOSACH ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 RITE FOR SERVICES ............................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 RITE FOR SELICHOT ............................................................................................................................................ 1 1.3 NOSACH FOR KADDISH ....................................................................................................................................... 1 1.4 PRONUNCIATION ............................................................................................................................................... 1 1.5 LUACH ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 2. WHO MAY SERVE AS SH’LIACH TZIBUR .......................................................................................................... 2 2.1 SH’LIACH TZIBUR MUST BE APPOINTED .................................................................................................................. 2 2.2 QUALIFICATIONS TO SERVE AS SH’LIACH TZIBUR ..................................................................................................... -

Selected Shavuot Halachot First Night

SELECTED SHAVUOT HALACHOT FIRST NIGHT (SUNDAY MAY 16) 1. On Sunday evening, first night Shavuot, many have the minhag to only daven Maariv at night fall. This is based on a well-established custom, cited in the Magen Avraham, not to bring in the Yom Tov of Shavuot early so as to complete the final, 49th, day of the Omer. This inevitably leads to a very late start to the Seuda, and must be weighed against the diminution in Simchat Yom Tov if one eats at a time at which one will not have appetite or when it will be too late for some members of the family to participate. For this reason we offer two times for Kabbalat Yom Tov: Mincha followed Maariv at 7.15pm, with the earliest time for Hadlakat HaNerot at 7.10pm. Kiddush and the meal can then be made immediately upon one's return home from shul. Latest time for start of Yom Tov and Mincha at 8.33pm, followed by a shiur and late Maariv at 9.39pm 2. For those who say Yizkor, many have the minhag to light a Yahrzheit candle in advance of Chaggim on which we say Yizkor. On Yom Tov we can only light from pre-existing flames. For this reason, a 24 or 48 hour candle might be useful for lighting the second day candles and for those who will wish to light their gas stove tops over Yom Tov TIKKUN LEYL 3. Please see HERE for full details of our communal Tikkun Leyl learning programmes, including for main learning programme, Youth and Lehava (young ladies) 4. -

Shabbos Sunday Sunday Night

Shabbos, 4 Sivan, 5781 - For local candle Your complete guide to this week's Friday, lighting times visit halachos and minhagim. 10 Sivan, 5781 Chabad.org/Candles Kabbolas Hatorah • Give extra tzedakah today for the two days of 3 Besimchah U’vipnimiyus! Shavuos. Hadlakas Neiros • Before Yom Tov, “Shavuos is a light a long-burning suitable time Shabbos candle, from which to accomplish 4 Sivan 5781 | Parshas Bamidbar the Yom Tov candles everything for the benefit of Torah can be lit tomorrow study and avodah Things to do night. with yiras shamayim, • Ideally, women as well as to do • The sefirah of Friday night is 48 days of the omer. and girls should teshuvah concerning • After Minchah, read the 6th chapter of Pirkei light candles Torah study, without Avos. before shekiah.4 hindrance from the • The sefirah of motzoei Shabbos is 49 days of the Satan. In this aspect, The berachos it is similar to when omer. of Lehadlik Ner the Shofar is blown Shel Yom Tov and on Rosh Hashanah Shehechiyanu are and to Yom Kippur” said. (Hayom Yom, 4 Sivan). Sunday 5 Sivan, 5781 | Erev Shavuos Things to do Sunday night 6 Sivan, 5781 | First night of Shavuos • Today is the date when the Jewish nation announced “Naaseh venishma,” prefacing Things to do naaseh to nishma. Over the course of the day, reflect on this event and how it applies to us, that • We are careful to begin Maariv tonight after tzeis when serving Hashem, we must first act and only hakochavim, so the forty-nine days of sefiras then try to understand.1 ha’omer will be complete.5 • The Rebbe would often make a siyum on • Say the Shemoneh Esrei for Shalosh Regalim, Maseches Sotah during the farbrengen of Erev inserting the additions for Shavuos where Shavuos. -

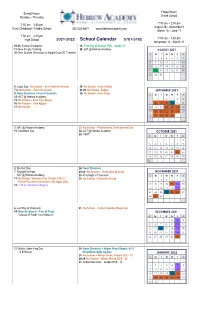

School Calendar 2021-2022

School Hours: Friday Hours: Monday – Thursday Entire School 7:50 am – 2:30 pm 7:50 am – 3:50 pm August 28 – November 5 Early Childhood – Middle School 305-532-6421 www.hebrewacademy.org March 18 – June 17 7:50 am – 4:15 pm 7:50 am – 1:30 pm High School 2021-2022 School Calendar 5781-5782 November 12 – March 11 16-20- Faculty Orientation 23- First Day of School, ECE – Grade 12 17- New Faculty Training 29- SAT @ Hebrew Academy AUGUST 2021 20- New Student Orientation & Supply Drop Off, Tentative S M T W Th F S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 6- Labor Day - No School – Erev Rosh Hashanah 20- No School – Erev Sukkot 7-8- No School – Rosh Hashanah 21-29- No School -Sukkot SEPTEMBER 2021 9- Noon Dismissal – Fast of Gedaliah 30- No School – Isru Chag S M T W Th F S 12- ACT @ Hebrew Academy 15- No School – Erev Yom Kippur 1 2 3 4 16- No School – Yom Kippur 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 17- No School 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 3- SAT @ Hebrew Academy 22- No School – Professional Development Day 11- Columbus Day 24- ACT @ Hebrew Academy OCTOBER 2021 26- PSAT S M T W Th F S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 2- Election Day 24- Noon Dismissal 7- Daylight Savings 25-26- No School – Thanksgiving Break NOVEMBER 2021 - SAT @ Hebrew Academy 28- First Night of Chanukah S M T W Th F S 11- No School, Veterans Day, Grades ECE-12 29- No School - Chanukah Break 1 2 3 4 5 6 - Parent/Teacher Conferences, By Appt.