7 Mirza Ghulam Ahmad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roll Number.Pdf

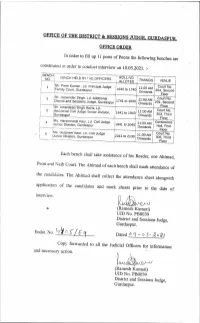

POST APPLIED FOR :- PEON Roll No. Application No. Name Father’s Name/ Husband’s Name Permanent Address 1 284 Aakash Subash Chander Hno 241/2 Mohalla Nangal Kotli Mandi Gurdaspur 2 792 Aakash Gill Tarsem lal Village Abulkhair Jail Road, Gurdaspur 3 1171 Aakash Masih Joginder Masih Village Chuggewal 4 1014 Aakashdeep Wazir Masih Village Tariza Nagar, PO Dhariwal, Gurdaspur 5 2703 Abhay Saini Parvesh Saini house no DF/350,4 Marla Quarter Ram Nagar Pathankot 6 1739 Abhi Bhavnesh Kumar Ward No. 3, Hno. 282, Kothe Bhim Sen, Dinanagar 7 1307 Abhi Nandan Niranjan Singh VPO Bhavnour, tehsil Mukerian , District Hoshiarpur 8 1722 Abhinandan Mahajan Bhavnesh Mahajan Ward No. 3, Hno. 282, Kothe Bhim Sen, Dinanagar 9 305 Abhishek Danial Hno 145, ward No. 12, Line No. 18A Mill QTR Dhariwal, District Gurdaspur 10 465 Abhishek Rakesh Kumar Hno 1479, Gali No 7, Jagdambe Colony, Majitha Road , Amritsar 11 1441 Abhishek Buta Masih Village Triza Nagar, PO Dhariwal, Gurdaspur 12 2195 Abhishek Vijay Kumar Village Meghian, PO Purana Shalla, Gurdaspur 13 2628 Abhishek Kuldeep Ram VPO Rurkee Tehsil Phillaur District Jalandhar 14 2756 Abhishek Shiv Kumar H.No.29B, Nehru Nagar, Dhaki road, Ward No.26 Pathankot-145001 15 1387 Abhishek Chand Ramesh Chand VPO Sarwali, Tehsil Batala, District Gurdaspur 16 983 Abhishek Dadwal Avresh Singh Village Manwal, PO Tehsil and District Pathankot Page 1 POST APPLIED FOR :- PEON Roll No. Application No. Name Father’s Name/ Husband’s Name Permanent Address 17 603 Abhishek Gautam Kewal Singh VPO Naurangpur, Tehsil Mukerian District Hoshiar pur 18 1805 Abhishek Kumar Ashwani Kumar VPO Kalichpur, Gurdaspur 19 2160 Abhishek Kumar Ravi Kumar VPO Bhatoya, Tehsil and District Gurdaspur 20 1363 Abhishek Rana Satpal Rana Village Kondi, Pauri Garhwal, Uttra Khand. -

Download Book

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES THE RELIGIOUS LIFE OF INDIA EDITED BY J. N. FARQUHAR, M.A., D.Litt. LITERARY SECRETARY, NATIONAL COUNCIL, YOUNG MEN'S CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATIONS, INDIA AND CEYLON ; AND NICOL MACNICOL, M.A., D.Litt. ALREADY PUBLISHED THE VILLAGE GODS OF SOUTH INDIA. By the Bishop OF Madras. VOLUMES UNDER PREPARATION THE VAISHNAVISM OF PANDHARPUR. By NicoL Macnicol, M.A., D.Litt., Poona. THE CHAITANYAS. By M. T. Kennedy, M.A., Calcutta. THE SRI-VAISHNAVAS. By E. C. Worman, M.A., Madras. THE SAIVA SIDDHANTA. By G. E. Phillips, M.A., and Francis Kingsbury, Bangalore. THE VIRA SAIVAS. By the Rev. W. E. Tomlinson, Gubbi, Mysore. THE BRAHMA MOVEMENT. By Manilal C. Parekh, B.A., Rajkot, Kathiawar. THE RAMAKRISHNA MOVEMENT. By I. N. C. Ganguly, B.A., Calcutta. THE StJFlS. By R. Siraj-ud-Din, B.A., and H. A. Walter, M.A., Lahore. THE KHOJAS. By W. M. Hume, B.A., Lahore. THE MALAS and MADIGAS. By the Bishop of Dornakal and P. B. Emmett, B.A., Kurnool. THE CHAMARS. By G. W. Briggs, B.A., Allahabad. THE DHEDS. By Mrs. Sinclair Stevenson, M.A., D.Sc, Rajkot, Kathiawar. THE MAHARS. By A. Robertson, M.A., Poona. THE BHILS. By D. Lewis, Jhalod, Panch Mahals. THE CRIMINAL TRIBES. By O. H. B. Starte, I.C.S., Bijapur. EDITORIAL PREFACE The purpose of this series of small volumes on the leading forms which religious life has taken in India is to produce really reliable information for the use of all who are seeking the welfare of India, Editor and writers alike desire to work in the spirit of the best modern science, looking only for the truth. -

TOP TEN MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT ISLAM by : Huma Ahmad

TOP TEN MISCONCEPTIONS ABOUT ISLAM by : Huma Ahmad MISCONCMISCONCEPTIONEPTION #1: Muslims are violent, terrorists and/or extremists. This is the biggest misconception in Islam, no doubt resulting from the constant stereotyping and bashing the media gives Islam. When a gunman attacks a mosque in the name of Judaism, a Catholic IRA guerrilla sets off a bomb in an urban area, or Serbian Orthodox militiamen rape and kill innocent Muslim civilians, these acts are not used to stereotype an entire faith. Never are these acts attributed to the religion of the perpetrators. Yet how many times have we heard the words 'Islamic, Muslim fundamentalist, etc.' linked with violence. Politics in so called "Muslim countries" may or may not have any Islamic basis. Often dictators and politicians will use the name of Islam for their own purposes. One should remember to go to the source of Islam and separate what the true religion of Islam says from what is portrayed in the media. Islam literally means 'submission to God' and is derived from a root word meaning 'peace'. Islam may seem exotic or even extreme in the modern world. Perhaps this is because religion doesn't dominate everyday life in the West, whereas Islam is considered a 'way of life' for Muslims and they make no division between secular and sacred in their lives. Like Christianity, Islam permits fighting in self- defense, in defense of religion, or on the part of those who have been expelled forcibly from their homes. It lays down strict rules of combat which include prohibitions against harming civilians and against destroying crops, trees and livestock. -

Orthopedically Handicapped (OH) Category 1 81 Raj Kumar S/O Ashok 70, Isa Nagasr , Batala, 10.09.1983 OH 20% Kumar Distt

Department of Local Government Punjab (Punjab Municipal Bhawan, Plot No.-3, Sector-35 A, Chandigarh) Detail of application for the posts of Safai Karamchari (Service Group-D) reserved for Disabled Persons in the cadre of Municipal Corporations and Municipal Councils-Nagar Panchayats in Punjab Sr. App Name of Candidate Address Date of Birth VH, HH, OH No. No. and Father’s Name etc. %age of Sarv Shri/ Smt./Miss Disability 1 2 3 4 5 6 Orthopedically Handicapped (OH) Category 1 81 Raj Kumar S/o Ashok 70, Isa Nagasr , Batala, 10.09.1983 OH 20% Kumar Distt. Gurdaspur (143505) Disability less then 40% 2 94 Manjeet Kaur D/o Vill. Mann, Teh. & Distt. 26.03.1999 OH 75% Pritam Singh Gurdaspur 3 103 Sukhbir Kaur D/o Vill. Ratta, Teh.- Dera 17.03.1998 OH 50% Sukhdev Singh Baba Nanak, Distt.- Gurdaspur 4 111 Rajesh Kumar S/o New Colony, ITI 12.02.1978 OH 74 % Baldev Raj Gurdaspur, Teh & Distt.- Gurdaspur 5 147 Ranjeet Singh S/o Dalla Kalan, P.O. Kadian, 05.02.1966 OH 40% Darshan Singh Distt- Gurdaspur, 143516 6 224 Rajinder Kumar S/o VPO Khojepur, Distt.& 18.03.1980 OH 55% Anchal Dass Teh. Gurdaspur. 7 279 Anil Kumar S/o Om VPO- Marara, Teh. & 09.07.1992 OH 60% Parkash Distt. Gurdaspur-143525. 8 331 Kuldeep Sharma S/o Vill. Dabur, P.O Magar 01.08.1988 OH 60% Darshan Kumar Mudia, Gurdaspur 9 335 Amandeep Singh S/o Vill. Raowal, P.O Deena 12.07.1992 OH 51% Karnail Singh Nagar, Teh. -

Women's Rights in Islam Regarding Marriage and Divorce Imani Jaafar-Mohammad

Journal of Law and Practice Volume 4 Article 3 2011 Women's Rights in Islam Regarding Marriage and Divorce Imani Jaafar-Mohammad Charlie Lehmann Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/lawandpractice Part of the Family Law Commons Recommended Citation Jaafar-Mohammad, Imani and Lehmann, Charlie (2011) "Women's Rights in Islam Regarding Marriage and Divorce," Journal of Law and Practice: Vol. 4, Article 3. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/lawandpractice/vol4/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Law and Practice by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Women's Rights in Islam Regarding Marriage and Divorce Keywords Muslim women--Legal status laws etc., Women's rights--Religious aspects--Islam, Marriage (Islamic law) This article is available in Journal of Law and Practice: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/lawandpractice/vol4/iss1/3 Jaafar-Mohammad and Lehmann: Women's Rights in Islam Regarding Marriage and Divorce WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN ISLAM REGARDING MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE 4 Wm. Mitchell J. L. & P. 3* By: Imani Jaafar-Mohammad, Esq. and Charlie Lehmann+ I. INTRODUCTION There are many misconceptions surrounding women’s rights in Islam. The purpose of this article is to shed some light on the basic rights of women in Islam in the context of marriage and divorce. This article is only to be viewed as a basic outline of women’s rights in Islam regarding marriage and divorce. -

Repair Programme 2018-19 Administr Ative Detail of Repair Sr

Repair Programme 2018-19 Administr ative Detail of Repair Sr. Approval Name of Name Xen/Mobile No. Distt. MC Name of Work No. Strengthe Premix Contractor/Agency Name of SDO/Mobile No. Length Cost Raising ning Carepet in in Km. in lacs in Km in Km Km 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Er. Anup Singh=98150-63540 Er. 1 Gurdaspur Batala SAROOPWALI TO AMRITSAR ROAD 1.05 14.54 0.07 0.98 1.05 A.B.S Engineers Amandeep Singh=7355700300 TALWANDI BHARTH TO SHAMSHAN Er. Anup Singh=98150-63540 Er. 2 Gurdaspur Batala 1.58 23.15 0.24 0.96 1.5 A.B.S Engineers GHAT UPTO PMGSY ROAD Amandeep Singh=7355700300 SAIDPUR KALAN SHAMSHANGHAT Er. Anup Singh=98150-63540 Er. 3 Gurdaspur Batala ROAD TO KASTIWAL ROAD 1.7 18.39 1.49 1.7 A.B.S Engineers Amandeep Singh=7355700300 ALONGWITH CANAL BT-FGC road to Bullowal Khokhar Er. Anup Singh=98150-63540 Er. 4 Gurdaspur Batala 2.65 26.1 1.18 2.65 A.B.S Engineers UPTO SHANKARPUR ROAD Amandeep Singh=7355700300 BATALA SGHPUR ROAD TO Er. Anup Singh=98150-63540 Er. 5 Gurdaspur Batala 1.81 21.99 1.39 1.81 C.&C Construction Co. PARTAPGARH AND PHIRNI Amandeep Singh=7355700300 BATALA,S.H.G PUR,BAHADUR- Er. Anup Singh=98150-63540 Er. 6 Gurdaspur Batala 1.31 19.35 0.42 0.73 1.31 C.&C Construction Co. HUSSAIN AND PHIRNI Amandeep Singh=7355700300 BATALA,BEAS,CHAHAL-KHURD, Er. Anup Singh=98150-63540 Er. -

Zaheeruddin V. State and the Official Persecution of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 5 June 1996 Enforced Apostasy: Zaheeruddin v. State and the Official Persecution of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan M. Nadeem Ahmad Siddiq Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation M. N. Siddiq, Enforced Apostasy: Zaheeruddin v. State and the Officialersecution P of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan, 14(1) LAW & INEQ. 275 (1996). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol14/iss1/5 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Enforced Apostasy: Zaheeruddin v. State and the Official Persecution of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan M. Nadeem Ahmad Siddiq* Table of Contents Introduction ............................................... 276 I. The Ahmadiyya Community in Islam .................. 278 II. History of Ahmadis in Pakistan ........................ 282 III. The Decision in Zaheerudin v. State ................... 291 A. The Pakistan Court Considers Ahmadis Non- M uslim s ........................................... 292 B. Company and Trademark Laws Do Not Prohibit Ahmadis From Muslim Practices ................... 295 C. The Pakistan Court Misused United States Freedom of Religion Precedent .............................. 299 D. Ordinance XX Should Have Been Found Void for Vagueness ......................................... 314 E. The Pakistan Court Attributed False Statements to Mirza Ghulam Almad ............................. 317 F. Ordinance XX Violates -

What Native Christians in the Middle East Continue to Face: Why It Matters for Both the Caring and the Unconcerned

What Native Christians in the Middle East Continue to Face: Why it Matters for Both the Caring and the Unconcerned By Habib C. Malik [The annual Earl A. Pope Guest Lecture in World Christianity, delivered at Lafayette College, Easton, Pennsylvania, on Tuesday, April 12, 2016, at 7:00 pm.] There have been Christians and Christian communities living in the Middle East since the dawn of Christianity. After the better part of twenty centuries in and around the Land of the Lord’s Incarnation and Resurrection, however, the presence of these native Christians is threatened with nothing less than termination. What exists today of these communities are the few tenacious remnants scattered throughout the Levant, Iraq, and Egypt of the earlier far larger and more geographically prevalent ones that have steadily dwindled over time due to sustained stresses and pressures brought on historically for the most part from the encounter with Islam. Today, in the early 21st century, the rise of militant and violent Islamism combined with a pervading apathy in the wider world as to the plight of these beleaguered Christian communities threaten to hasten the final demise of Christianity in and around its original birthplace. The bleak future for Christians native to the Middle East, I submit to you tonight, relates organically to the state of Christians and Christianity in today’s largely post-Christian secular Europe, and in the West as a whole. Many will dismiss this alleged connection out of hand, but it continues to impose itself thunderously in the face of all such denial and disinterest. -

Non-Muslim Integration Into the Early Islamic Caliphate Through the Use of Surrender Agreements

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK History Undergraduate Honors Theses History 5-2020 Non-Muslim Integration Into the Early Islamic Caliphate Through the Use of Surrender Agreements Rachel Hutchings Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/histuht Part of the History of Religion Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Citation Hutchings, R. (2020). Non-Muslim Integration Into the Early Islamic Caliphate Through the Use of Surrender Agreements. History Undergraduate Honors Theses Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/histuht/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Non-Muslim Integration Into the Early Islamic Caliphate Through the Use of Surrender Agreements An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of Honors Studies in History By Rachel Hutchings Spring 2020 History J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences The University of Arkansas 1 Acknowledgments: For my family and the University of Arkansas Honors College 2 Table of Content Introduction…………………………………….………………………………...3 Historiography……………………………………….…………………………...6 Surrender Agreements…………………………………….…………….………10 The Evolution of Surrender Agreements………………………………….…….29 Conclusion……………………………………………………….….….…...…..35 Bibliography…………………………………………………………...………..40 3 Introduction Beginning with Muhammad’s forceful consolidation of Arabia in 631 CE, the Rashidun and Umayyad Caliphates completed a series of conquests that would later become a hallmark of the early Islamic empire. Following the Prophet’s death, the Rashidun Caliphate (632-661) engulfed the Levant in the north, North Africa from Egypt to Tunisia in the west, and the Iranian plateau in the east. -

A Message of Peace and a Word of Warning

A Message of Peace And a Word of Warning by Hadhrat Mirza Nasir Ahmad rh Khalifatul Masih III A Message of Peace and a Word of Warning A lecture delivered by Hadrat Mirza Nasir Ahmadrh, Khalifatul Masih III, on 28th July 1967, at Wandsworth Town Hall, London. © Islam International Publications Ltd. First Edition published undated by the Oriental and Religious Publishing Corporation Ltd, Rabwah, Pakistan. First Edition published in UK in 2006 First Edition Published in India in 2008 Present Edition Published in India in September 2014 Copies: 2000 Published By: Nazarat Nashr-o-Isha’at, Sadr Anjuman Ahmadiyya Qadian, Distt Gurdaspur, Punjab – 143516, India. Printed in India at: Fazle Umar Printing Press Qadian. ISBN: 978-81-7912-202-0 ABOUT THE AUTHOR rh Hadrat Hafiz Mirza Nasir Ahmad M.A. (Oxon)–1909–1982–of blessed memory, the third Manifestation of Divine Providence, the Imam of the International Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama‘at, the Voice Articulate of God, sign and fulfillment of His Promise and the Promised Grandson was elected as the third successor (Khalifa) of the Promised as Messiah and Mahdi on November 8, 1965 on the demise of his great and illustrious father, the second successor of the Promised as Messiah , Hadrat Mirza Bashirud Din ra Mahmood Ahmad , al-Muslih Ma‘ud (the Promised Reformer). He occupied this exalted spiritual station for seventeen years till his death, and as the Promised as Grandson of the Promised Messiah , he was a Sign of Allah Who bestowed on him His special Graces and Favours from the time of his birth to his death. -

Pakistan: Massacre of Minority Ahmadis | Human Rights Watch

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH http://www.hrw.org Pakistan: Massacre of Minority Ahmadis Attack on Hospital Treating Victims Shows How State Inaction Emboldens Extremists The mosque attacks and the June 1, 2010 subsequent attack on the hospital, amid rising sectarian violence, (New York) – Pakistan’s federal and provincial governments should take immediate legal action underscore the vulnerability of the against Islamist extremist groups responsible for threats and violence against the minority Ahmadiyya Ahmadi community. religious community, Human Rights Watch said today. Ali Dayan Hasan, senior South Asia researcher On May 28, 2010, extremist Islamist militants attacked two Ahmadiyya mosques in the central Pakistani city of Lahore with guns, grenades, and suicide bombs, killing 94 people and injuring well over a hundred. Twenty-seven people were killed at the Baitul Nur Mosque in the Model Town area of Lahore; 67 were killed at the Darul Zikr mosque in the suburb of Garhi Shahu. The Punjabi Taliban, a local affiliate of the Pakistani Taliban, called the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), claimed responsibility. On the night of May 31, unidentified gunmen attacked the Intensive Care Unit of Lahore’s Jinnah Hospital, where victims and one of the alleged attackers in Friday's attacks were under treatment, sparking a shootout in which at least a further 12 people, mostly police officers and hospital staff, were killed. The assailants succeeded in escaping. “The mosque attacks and the subsequent attack on the hospital, amid rising sectarian violence, underscore the vulnerability of the Ahmadi community,” said Ali Dayan Hasan, senior South Asia researcher at Human Rights Watch. -

Aqasi, Haji Mirza (‘Abbas Iravani) (C

Aqasi, Haji Mirza (‘Abbas Iravani) (c. 1783–1849) Prime minister of Iran under Muhammad Shah Qajar from 1835 to 1848; regarded by Bahá’ís as the Antichrist of the Bábí dispensation. ARTICLE OUTLINE: LIFE Life Haji Mirza Aqasi, whose given name was ‘Abbas Relations with the Báb and Bábís Iravani, was born and raised in Mákú, Azerbaijan, Haji Mirza Aqasi in the Bábí and Bahá’í in northwestern Iran. His father was a mullá and Writings small landowner from Yerevan, Armenia. During ARTICLE RESOURCES: his youth Mírzá ‘Abbás Íravání studied with Mullá ‘Abdu’s-Samad, a guide and elder of the Notes Ni‘matu’lláhí Sufi order, in the holy city of Karbala Other Sources and Selected Reading in Iraq. Mírzá ‘Abbás Íravání then spent a period of time living as a dervish, wandering from place to place, before taking up residence in Yerevan. Later he went to Tabriz, where he was employed by Mírzá Buzurg Qá’im-Maqám as a tutor to one of his sons, Músá, and gained both rank and wealth. Mírzá Buzurg gave him the title Aqasi (Chief Officer of the Household) by which he was subsequently known. After his patron’s death in 1821, factionalism stemming from the rivalry between Mírzá Buzurg’s sons caused Aqasi to fall into disfavor for a time, but by 1824 he was back in Tabriz, tutoring several of the sons of the crown prince, ‘Abbás Mírzá. In his position as tutor, Aqasi succeeded in becoming the confidant and spiritual guide of Muhammad Mírzá (b. 1808), the crown prince’s eldest son, who acceded to the throne as Muhammad Shah in 1834.