Revisiting Hampstead Garden Suburb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Raymond Unwin (1863 – 1940)

Raymond Unwin (1863 – 1940) Raymond Unwin was born on 2nd November 1863 in Whiston, Rotherham, the younger son of William Unwin, a tutor at Balliol College, Oxford and his wife Elizabeth Sully. He considered entering the Church of England, as his elder brother William did, but he was diverted, to his father's disappointment, into a life of social activism. Unwin was educated at Magdalen College Choir School, Oxford, where he became aware of the Socialist principles of John Ruskin and William Morris. In 1883, he settled in Chesterfield as an engineering apprentice at the Staveley Coal and Iron Company, and came into contact with the Socialist philosopher Edward Carpenter at Millthorpe, Sheffield. In 1885 he obtained a post as an engineering draughtsman in Manchester where he was the local secretary of William Morris's Socialist League, writing articles for its newspaper 'Commonweal'. In 1887 he returned to the Staveley Coal and Iron Company in Barrow Hill as a draughtsman, and although he had no training in architecture, he was working primarily as an architect and was part of the Company team who designed housing at Barrow Hill, Duckmanton and Poolsbrook. At one point, he “offered to resign if bathrooms were not provided to dwellings at Allport Terrace, Barrow Hill.”i Unwin married his cousin, Ethel Parker, in 1893, the same year that he received his first major architectural commission - to build St Andrew’s Church at Barrow Hill. This was completed largely alone, with some collaboration with his brother -in-law, (Richard) Barry Parker. Parker, was staying with the Unwins at Chapel- en-le-Frith when Unwin was building St Andrew’s, and designed a mosaic glass reredos for it. -

Freeholders Benefit As Court Upholds Trust Decision

THE TRUST P u b l i s h e d b y t h e h a m P s t e a d G a r d e n s u b u r b t r u s t l i m i t e d Issue no. 10 sePtember 2012 Freeholders benefit as Court upholds Trust decision The Management Charge for the The Court ordered that the owner of The Court held that the Trust was financial year 2011/2012 has been 25 Ingram Avenue must pay the Trust’s acting in the public interest. The held steady at the same level as costs in defending, over a period of decision sets an important precedent the previous year – and there is a five years, a refusal of Trust consent for the future of the Scheme of further benefit for freeholders. for an extension. The Trust is in turn Management – and is doubly good passing the £140,000, recovered in news for charge payers. In August last year freeholders March 2012, back to charge payers. received a bill for £127. However, this THE GAZETTE AT A GLANCE year, owners of property that became The Court of Appeal ruled in freehold before 5 April 2008 will receive November 2011 that the Trust had Trust Decision Upheld ........................ 1 a bill for only £85 – thanks largely to been right to refuse consent for an Suburb Trees ........................................ 2 judges in the Court of Appeal. extension that would have encroached Hampstead Heritage Trail .................. 3 on the space between houses, Education ............................................. 5 The Hampstead contravened the Design Guidance and Garden Suburb Trust set an undesirable precedent across Trust Committees .............................. -

Capital Ring Section 11 Hendon Park to Highgate

Capital Ring Directions from Hendon Central station: From Hendon Central Station Section 11 turn left and walk along Queen’s Road. Cross the road opposite Hendon Park gates and enter the park. Follow the tarmac path down through the Hendon Park to Highgate park and then the grass between an avenue of magnificent London plane and other trees. At the path junction, turn left to join the main Capital Ring route. Version 2 : August 2010 Directions from Hendon Park: Walk through the park exiting left onto Shirehall Lane. Turn right along Shirehall Close and then left into Shirehall Start: Hendon Park (TQ234882) Park. Follow the road around the corner and turn right towards Brent Street. Cross Brent Street, turn right and then left along the North Circular road. Station: Hendon Central After 150m enter Brent Park down a steep slope. A Finish: Priory Gardens, Highgate (TQ287882) Station: Highgate The route now runs alongside the River Brent and runs parallel with the Distance: 6 miles (9.6 km) North Circular for about a mile. This was built in the 1920s and is considered the noisiest road in Britain. The lake in Brent Park was dug as a duck decoy to lure wildfowl for the table; the surrounding woodland is called Decoy Wood. Brent Park became a public park in 1934. Introduction: This walk passes through many green spaces and ancient woodlands on firm pavements and paths. Leave the park turning left into Bridge Lane, cross over and turn right before the bridge into Brookside Walk. The path might be muddy and slippery in The walk is mainly level but there some steep ups and downs and rough wet weather. -

63 EAST END ROAD East Finchley, London N2 0SE

Site boundary line indicative only 63 EAST END ROAD East Finchley, London N2 0SE North London Residential Development Opportunity 63 East End Road East Finchley, London N2 0SE 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • Residential development opportunity located in East Finchley within the jurisdiction of the London Borough of Barnet. • The approximately 0.41 hectare (1.02 acre) walled site is occupied by a detached, early 19th Century villa, which has been extended and adapted over the years, set in attractive grounds. • Planning permission for redevelopment of the site to provide an all-private residential scheme comprising 15 houses, 12 new build and 3 of which will be formed by converting part of the existing Grade II Listed building. • The scheme will comprise 12x 2 Bedroom houses and 3x 3 Bedroom houses with a total Net Saleable Area of 1,639 sq m (17,638 sq ft). 19 car parking spaces will be provided. CGI’s of proposed scheme • Located approximately 1.3km from Finchley Central London Underground Station and 1.5km from East Finchley London Underground Station for access to Northern Line services. • For sale freehold with vacant possession CGI’s of proposed scheme CGI’s of proposed scheme 63 East End Road East Finchley, London N2 0SE 3 LOCATION AND DESCRIPTION The site is located within East Finchley, North London approximately 9 km (5.5 miles) from Central London. East Finchley is situated between Muswell Hill to the east, Hampstead Garden Suburb and Highgate to the south and south west and Finchley bounds it to the north, delineated by the North Circular Road (A406). -

Capital Ring Section 11 of 15

Transport for London. Capital Ring Section 11 of 15. Hendon Park to Priory Gardens, Highgate. Section start: Hendon Park. Nearest stations Hendon Central . to start: Section finish: Priory Gardens, Highgate. Nearest station Highgate . to finish: Section distance: 6 miles (9.6 kilometres). Introduction. This walk passes through many green spaces and ancient woodlands on firm pavements and paths. The walk is mainly level but there some steep ups and downs and rough ground, especially at the end towards Highgate station. This may be difficult for wheelchairs and buggies but it can be avoided by taking a parallel route. Interesting things to see along the way include the lake in Brent Park, once a duck decoy, the statue of 'La Delivrance' at Finchley Road, Hampstead Garden Suburb dating from 1907, the distinctive East Finchley Underground station opened in 1939 with its famous archer statue and the three woods - Cherry Tree, Highgate and Queen's Wood - all remnants of the ancient forest of Middlesex. There are pubs and cafes at Hendon Central, Northway, East Finchley, Highgate Wood and Queen's Wood. There are public toilets at Highgate Wood and Queen's Wood. There's an Underground station at East Finchley, as well as buses along the way. Continues Continues on next page Directions From Hendon Central station turn left and walk along Queen's Road. Cross the road opposite Hendon Park gates and enter the park. Follow the tarmac path down through the park and then the grass between an avenue of magnificent London plane and other trees. At the path junction (by the railway footbridge), turn left to join the main Capital Ring route. -

Hgstrust.Org London N11 1NP Tel: 020 8359 3000 Email: [email protected] (Add Character Appraisals’ in the Subject Line) Contents

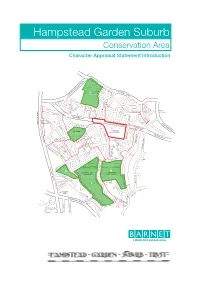

Hampstead Garden Suburb Conservation Area Character Appraisal Statement Introduction For further information on the contents of this document contact: Urban Design and Heritage Team (Strategy) Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust Planning, Housing and Regeneration 862 Finchley Road First Floor, Building 2, London NW11 6AB North London Business Park, tel: 020 8455 1066 Oakleigh Road South, email: [email protected] London N11 1NP tel: 020 8359 3000 email: [email protected] (add character appraisals’ in the subject line) Contents Section 1 Introduction 5 1.1 Hampstead Garden Suburb 5 1.2 Conservation areas 5 1.3 Purpose of a character appraisal statement 5 1.4 The Barnet unitary development plan 6 1.5 Article 4 directions 7 1.6 Area of special advertisement control 7 1.7 The role of Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust 8 1.8 Distinctive features of this character appraisal 8 Section 2 Location and uses 10 2.1 Location 10 2.2 Uses and activities 11 Section 3 The historical development of Hampstead Garden Suburb 15 3.1 Early history 15 3.2 Origins of the Garden Suburb 16 3.3 Development after 1918 20 3.4 1945 to the present day 21 Section 4 Spatial analysis 22 4.1 Topography 22 4.2 Views and vistas 22 4.3 Streets and open spaces 24 4.4 Trees and hedges 26 4.5 Public realm 29 Section 5 Town planning and architecture 31 Section 6 Character areas 36 Hampstead Garden Suburb Character Appraisal Introduction 5 Section 1 Introduction 1.1 Hampstead Garden Suburb Hampstead Garden Suburb is internationally recognised as one of the finest examples of early twentieth century domestic architecture and town planning. -

Henrietta Barnett: Co-Founder of Toynbee Hall, Teacher, Philanthropist and Social Reformer

Henrietta Barnett: Co-founder of Toynbee Hall, teacher, philanthropist and social reformer. by Tijen Zahide Horoz For a future without poverty There was always “something maverick, dominating, Roman about her, which is rarely found in women, though she was capable of deep feeling.” n 1884 Henrietta Barnett and her husband Samuel founded the first university settlement, Toynbee Hall, where Oxbridge students could become actively involved in helping to improve life in the desperately poor East End Ineighbourhood of Whitechapel. Despite her active involvement in Toynbee Hall and other projects, Henrietta has often been overlooked in favour of a focus on her husband’s struggle for social reform in East London. But who was the woman behind the man? Henrietta’s work left an indelible mark on the social history of London. She was a woman who – despite the obstacles of her time – accomplished so much for poor communities all over London. Driven by her determination to confront social injustice, she was a social reformer, a philanthropist, a teacher and a devoted wife. A shrewd feminist and political activist, Henrietta was not one to shy away from the challenges posed by a Victorian patriarchal society. As one Toynbee Hall settler recalled, Henrietta’s “irrepressible will was suggestive of the stronger sex”, and “there was always something maverick, dominating, Roman about her, which is rarely found in women, though she was capable of deep feeling.”1 (Cover photo): Henrietta in her forties. 1. Creedon, A. ‘Only a Woman’, Henrietta Barnett: Social Reformer and Founder of Hampstead Garden Suburb, (Chichester: Phillimore & Co. LTD, 2006) 3 A fourth sister had “married Mr James Hinton, the aurist and philosopher, whose thought greatly influenced Miss Caroline Haddon, who, as my teacher and my friend, had a dynamic effect on my then somnolent character.” The Early Years (Above): Henrietta as a young teenager. -

Synagogues with Secretaries (For Marriages) Certified to the Registrar General

Synagogues with Secretaries (for marriages) certified to the Registrar General DISTNAME BUILDNAME BARNET BARNET BARNET BARNET FINCHLEY BARNET BEIS KNESSES AHAVAS REIM SYNAGOGUE BARNET BRIDGE LANE BETH HAMEDRASH BARNET EDGWARE ADATH YISROEL BARNET EDGWARE AND DISTRICT REFORM BARNET EDGWARE MASORTI BARNET EDGWARE UNITED SYNAGOGUE BARNET EDGWARE YESHURIN BARNET ETZ CHAIM SYNAGOGUE BARNET FINCHLEY CENTRAL BARNET FINCHLEY PROGRESSIVE BARNET FINCHLEY REFORM BARNET GOLDERS GREEN BARNET GOLDERS GREEN BETH HAMEDRASH BARNET HAMPSTEAD GARDEN SUBURB BARNET HENDON BARNET HENDON ADATH YISROEL BARNET HENDON BEIS HAMEDRASH BARNET HENDON REFORM BARNET KOL NEFESH MASORTI SYNAGOGUE BARNET MACHZIKE HADATH BARNET MACHZIKEI HADASS SYNAGOGUE BARNET MILL HILL BARNET NER YISRAEL BARNET NEW NORTH LONDON BARNET NORTH HENDON ADATH YISROEL BARNET NORTH WEST SEPHARDISH BARNET NORTH WESTERN REFORM BARNET OD YOSEF CHAI YESHIVA COMMUNITY BARNET OHEL DAVID EASTERN BARNET SINAI BARNET SOUTHGATE AND DISTRICT REFORM BARNET THE NEW HENDON BEIS HAMEDRASH SYNAGOGUE BARNET WOODSIDE PARK BEDFORD BEDFORDSHIRE PROGRESSIVE SYNAGOGUE BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CENTRAL SYNAGOGUE BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM HEBREW CONGREGATION BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM PROGRESSIVE BLACKPOOL BLACKPOOL REFORM BLACKPOOL BLACKPOOL UNITED HEBREW CONGREGATION BLACKPOOL ST ANNES HEBREW CONGREGATION BOURNEMOUTH BOURNEMOUTH HEBREW CONGREGATION BOURNEMOUTH BOURNEMOUTH REFORM SYNAGOGUE BRADFORD AND KEIGHLEY BRADFORD HEBREW BRADFORD AND KEIGHLEY THE BRADFORD SYNAGOGUE BRENT BRONDESBURY PARK SYNAGOGUE BRENT DAVID ISHAG SYNAGOGUE -

The Work of Clarence S Stein, 1919-1939

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1977 The Work of Clarence S Stein, 1919-1939 Prudence Anne Phillimore College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Architecture Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Phillimore, Prudence Anne, "The Work of Clarence S Stein, 1919-1939" (1977). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624992. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-thx8-hf93 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE WORK OF CLARENCE S. STEIN 1919 - 1939 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Prudence Anne Phillimore 1977 APPROVAL, SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts f t . P t R u Autho r Approved, May 1977 1 8 Sii 7 8 8 \ TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE ABSTRACT ....................................................................................... iv INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 2 CHAPTER I STEIN'S EARLY LIFE AND THE INFLUENCES ON HIS WORK................... 10 CHAPTER II STEIN’S ACHIEVEMENTS IN HOUSING LEGISLATION IN NEW YORK STATE.. 37 CHAPTER III REGIONAL PLANNING: AN ALTERNATIVE SOLUTION TO THE HOUSING PROBLEM................................... -

From York to New Earswick: Working-Class Homes at the Turn of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Northumbria Research Link From York to New Earswick: working-class homes at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Cheryl Buckley School of Arts and Social Sciences Northumbria University Newcastle-upon-Tyne England NE1 8ST Work +44 (0) 191 227 3124 - Mob: 07792194339 Home +44 (0) 1325 484877 – Mob: 07814 278168 [email protected] [email protected] word count 3,844 1 How to improve the lives of the working class and the poor in Britain has been a key concern for social reformers, architects and designers, and local and national governments throughout twentieth century, but the origins of this were in the preceding century. From the middle of the nineteenth century, reformers had understood the necessity of improving the living conditions, diet and material environment of those with low incomes. Housing, at the core of this, was increasingly a political issue, but as this case study of the development of a garden village in the North of England demonstrates, it was also a moral and aesthetic one. Moving home from poor quality housing in York city centre to the garden village of New Earswick begun in 1903 symbolised not only a physical relocation a few miles north, but also an unprecedented change in social and material conditions. Life in New Earswick promised new opportunities; a chance to start afresh in carefully designed, better equipped housing located in a rural setting and with substantial gardens. Largely unexplored -

'Voices of the Suburb'

www.hgs.org.uk Issue 118 · Spring 2014 Suburb Directory 2014 Shiver me timbers! May 2014-April 2015 All you need to Leslie Garrett to All you need to know about living – pirates and fairies on the Suburb know about the perform at this year’s awash at RA party, Suburb in the new Proms at St Judes, see page 4 2014 Directory see page 5 MEMBERS SEE CENTREDISCOUNTS TO JOIN RA FOR AND ENJOY 40 LOCAL www.hgs.org.uk New faces at the RA The RA’s 102nd annual general HON LIFE MEMBERS cottage at 68 Willifield Way. CHAIRMAN AN meeting on March 31 saw Janet The RA occasionally confers This had been considered both INSPIRATION Elliott, chairman for the last five honorary life membership on sensitive and elegant. Presenting her with a Suburb years, hand over to Jonathan Seres. people who have, over a long The architect was Christian watercolor from the Garden Max Petersen became vice period, provided exceptional Clemares of XUL Architecture Suburb Gallery, Jonathan Seres chairman and Gary Shaw, scourge service to the Suburb. This year who was presented with the award. said Janet had been both an of Barnet’s parking dept, took over Hilda Williams who has looked inspiration and a pleasure to as hon secretary. Hon treasurer, after Fellowship House and its work with. He welcomed new Jeremy Clynes, stayed put. members for much of a very long and old members. He spoke of It was a good year for recruits life, accepted life membership the motivation for new residents to council with five new members as did Jenny and Brian Stonhold to join the RA, and said “The making up for the loss of Richard for their work with young people. -

Hgstrust.Org London N11 1NP Tel: 020 8359 3000 Email: [email protected] (Add ‘Character Appraisals’ in the Subject Line) Contents

Hampstead Garden Suburb Central Square – Area 1 Character Appraisal For further information on the contents of this document contact: Urban Design and Heritage Team (Strategy) Hampstead Garden Suburb Trust Planning, Housing and Regeneration 862 Finchley Road First Floor, Building 2, London NW11 6AB North London Business Park, tel: 020 8455 1066 Oakleigh Road South, email: [email protected] London N11 1NP tel: 020 8359 3000 email: [email protected] (add ‘character appraisals’ in the subject line) Contents Section 1 Background historical and architectural information 5 1.1 Location and topography 5 1.2 Development dates and originating architect(s) and planners 5 1.3 Intended purpose of original development 5 1.4 Density and nature of the buildings. 5 Section 2 Overall character of the area 6 2.1 Principal positive features 7 2.2 Principal negative features 9 Section 3 The different parts of the main area in greater detail 11 3.1 Erskine Hill and North Square 11 3.2 Central Square, St. Jude’s, the Free Church and the Institute 14 3.3 South Square and Heathgate 17 3.4 Northway, Southway, Bigwood Court and Southwood Court 20 Map of area Hampstead Garden Suburb Central Square, Area 1 Character Appraisal 5 Character appraisal Section 1 Background historical and architectural information 1.1 Location and topography Central Square was literally at the centre of the ‘old’ suburb but, due to the further development of the Suburb in the 1920s and 1930s, it is now located towards the west of the Conservation Area. High on its hill, it remains the focal point of the Suburb.