Structural Dream Analysis: a Narrative Research Method for Investigating

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Story of Napili Kai Beach Resort

The Unbeatable Dream The Unbeatable Dream The Story of Napili Kai Beach Resort by Jack, Margaret and Dorothy Millar as told to and written Margaret, Jack and Dorothy Millar, 1985. by Brooke Brown Dedication To the original eleven shareholders: Cece and Barbara Atkinson Herb and Donne Bliss Orbe and Edith Boake Del and Dorothy de La Mothe Jack and Grace Gregory Eileen Grove (now Nicholson) Ross and Eleanor Leydon Jack and Margaret Millar Slim and Helen Wheeler El and Pearl Williams Lloyd and Helen Williams Copyright © 1985 Napili Kai Ltd. and All Rights Reserved To all the other brave souls who over the years have 1st Edition Published 1985 risked their investment monies to build the dream 2nd Edition 1986 and 3rd Edition 1989 To all future believers in the dream who will risk 4th Edition 1996 5th Edition 2008 their monies to see it all bear fruit Originally Edited and Produced by Richard P. Wirtz Studio Maui 4th and 5th Editions Produced by Catapult Communications, Inc. Pukalani, Hawaii Printed in the United States by Hagadone Printing Company Honolulu, Hawaii iv v CHAPTER ELEVEN Contents Living the Dream . 101 Foreword...................... .ix CHAPTER TWELVE CHAPTER ONE A Flood of Support. 107 Love at First Sight ............... 1 CHAPTER THIRTEEN CHAPTER TWO The End of an Era ..............111 Building the Dream .............. 7 CHAPTER FOURTEEN CHAPTER THREE Dawn of a New Era .............117 Onward and Upward ............ 13 CHAPTER FIFTEEN CHAPTER FOUR Five Difficult, But Rewarding, Years 123 Angels in the Dream ............ 23 CHAPTER SIXTEEN CHAPTER FIVE The (Tea) Sea House...... Story . 129 Down Came Baby, Mountside and All 47 CHAPTER SEVENTEEN CHAPTER SIX Changing of the Guard . -

A DANGEROUS METHOD a Sony Pictures Classics Presentation a Jeremy Thomas Production

MOVIE REVIEW Afr J Psychiatry 2012;15:363 A DANGEROUS METHOD A Sony Pictures Classics Presentation A Jeremy Thomas Production. Directed by David Cronenberg Film reviewed by Franco P. Visser As a clinician I always found psychoanalysis and considers the volumes of ethical rules and psychoanalytic theory to be boring, too intellectual regulations that govern our clinical practice. Jung and overly intense. Except for the occasional was a married man with children at the time. As if Freudian slip, transference encountered in therapy, this was not transgression enough, Jung also the odd dream analysis around the dinner table or became Spielrein’s advisor on her dissertation in discussing the taboos of adult sexuality I rarely her studies as a psychotherapist. After Jung’s venture out into the field of classic psychoanalysis. attempts to re-establish the boundaries of the I have come to realise that my stance towards doctor-patient relationship with Spielrein, she psychoanalysis mainly has to do with a lack of reacts negatively and contacts Freud, confessing knowledge and specialist training on my part in everything about her relationship with Jung to him. this area of psychology. I will also not deny that I Freud in turn uses the information that Spielrein find some of the aspects of Sigmund Freud’s provided in pressuring Jung into accepting his theory and methods highly intriguing and at times views and methods on the psychological a spark of curiosity makes me jump into the pool functioning of humans, and it is not long before the of psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic theory and two great minds part ways in addition to Spielrein ‘swim’ around a bit – mainly by means of reading or surfing the going her own way. -

ATLANTA DREAM (7-3) Vs. WASHINGTON MYSTICS (5-6) June 18, 2014 • 12:00 P.M

ATLANTA DREAM (7-3) vs. WASHINGTON MYSTICS (5-6) June 18, 2014 • 12:00 p.m. ET • TV: FSS Philips Arena • Atlanta, Ga. Regular Season Game 11 • Home Game 7 2014 Schedule & Results PROBABLE STARTERS Date .........Opponent ....................Result/Time Pos. No. Player PPG RPG APG Notes May 11 ..... NEW YORK^ .......................W, 63-58 G 5 JASMINE THOMAS 8.9 2.0 2.1 Has raised her scoring average every May 16 ..... SAN ANTONIO (SPSO) ....W, 79-75 5-9 • 145 • Duke season May 17 ..... at Indiana (FSS) .......W, 90-88 (2OT) Leads the league in 3-point field goal May 24 ..... at Chicago (NBA TV) .......... L, 73-87 10.2 2.8 1.7 G 15 TIFFANY HAYES pct. (.583) May 25 ..... INDIANA (SPSO) ...... L, 77-82 (OT) 5-10 • 155 • Connecticut May 30 ..... SEATTLE (SPSO) ................W, 80-69 G 35 ANGEL McCOUGHTRY 18.3 4.8 4.3 Fifth in the league in steals (2.4), sixth June 1 ....... at Connecticut ....................... L, 76-85 in scoring, tied for 11th in assists June 3 ....... LOS ANGELES (ESPN2) ....W, 93-85 6-1 • 160 • Louisville June 7 ....... CHICAGO (SPSO) ..............W, 97-59 F 20 SANCHO LYTTLE 11.6 9.5 2.3 Has scored in double figures seven June 13 .... MINNESOTA (SPSO) .........W, 85-82 6-4 • 175 • Houton straight games (13.7 ppg) June 15 .... at Washington ......................W, 75-67 June 18 .... WASHINGTON (FSS) .............12 pm C 14 ERIKA DE SOUZA 18.0 9.6 1.3 Only player in the WNBA averaging at June 20 .... NEW YORK (SPSO) .............7:30 pm 6-5 • 190 • Brazil least 18 points and nine rebounds June 22 ... -

On Dreams” (1900-01)

SIGMUND FREUD Excerpts from “On Dreams” (1900-01) VI It is the process of displacement which is chiefly responsible for our being unable to discover or recognize the dream-thoughts in the dream-content, unless we understand the reason for their distortion. Nevertheless, the dream-thoughts are also submitted to another and milder sort of transformation, which leads to our discovering a new achievement on the part of the dream-work –one, however, which is easily intelligible. The dream-thoughts which we first come across as we proceed with our analysis often strike us by the unusual form in which they are expressed; they are not clothed in the prosaic language usually employed by our thoughts, but are on the contrary represented symbolically by means of similes and metaphors, in images resembling those of poetic speech. There is no difficulty in accounting for the constraint imposed upon the form in which the dream-thoughts are expressed. The manifest content of dreams consists for the most part in pictorial situations; and the dream-thoughts must accordingly be submitted in the first place to a treatment which will make them suitable for a representation of this kind. If we imagine ourselves faced by the problem of representing the arguments in a political leading article or the speeches of counsel before a court of law in a series of pictures, we shall easily understand the modifications which must necessarily be carried out by the dream-work owing to considerations of representability in the content of the dream. The psychical material of the dream-thoughts habitually includes recollections of impressive experiences - not infrequently dating back to early childhood - which are thus themselves perceived as a rule as situations having a visual subject-matter. -

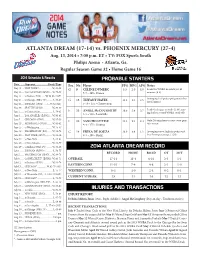

Aug. 13 Vs. Phoenix.Indd

ATLANTA DREAM (17-14) vs. PHOENIX MERCURY (27-4) Aug. 13, 2014 • 7:00 p.m. ET • TV: FOX Sports South Philips Arena • Atlanta, Ga. Regular Season Game 32 • Home Game 16 2014 Schedule & Results PROBABLE STARTERS Date .........Opponent ....................Result/Time Pos. No. Player PPG RPG APG Notes May 11 .....NEW YORK^ .......................W, 63-58 G 9 CÉLINE DUMERC 3.3 2.0 4.0 Leads the WNBA in assists per 40 May 16 .....SAN ANTONIO (SPSO) ....W, 79-75 5-7 • 145 • France minutes (8.9) May 17 .....at Indiana (FSS) .......W, 90-88 (2OT) Averaging 15.9 points per game in her May 24 .....at Chicago (NBA TV) .......... L, 73-87 G 15 TIFFANY HAYES 13.2 3.0 2.6 last 15 games May 25 .....INDIANA (SPSO) ...... L, 77-82 (OT) 5-10 • 155 • Connecticut May 30 .....SEATTLE (SPSO) ................W, 80-69 F 35 ANGEL McCOUGHTRY 19.0 5.4 3.7 Leads the league in steals (2.48), aim- June 1 .......at Connecticut .......................L, 76-85 ing for her second WNBA steals title June 3 .......LOS ANGELES (ESPN2) ....W, 93-85 6-1 • 160 • Louisville June 7 .......CHICAGO (SPSO) ..............W, 97-59 F 20 SANCHO LYTTLE 12.4 9.2 2.4 Only Dream player to start every game June 13 .... MINNESOTA (SPSO) .........W, 85-82 6-4 • 175 • Houton this season June 15 .... at Washington ......................W, 75-67 June 18 .... WASHINGTON (FSS) ........W, 83-73 C 14 ERIKA DE SOUZA 13.9 8.9 1.2 Averaging career highs in points and June 20 .... NEW YORK (SPSO) ...........W, 85-64 6-5 • 190 • Brazil free throw percentage (.720) June 22 ... -

Exploring a Jungian-Oriented Approach to the Dream in Psychotherapy

Exploring a Jungian-oriented Approach to the Dream in Psychotherapy By Darina Shouldice Submitted to the Quality and Qualifications Ireland (QQI) for the degree MA in Psychotherapy from Dublin Business School, School of Arts Supervisor: Stephen McCoy June 2019 Department of Psychotherapy Dublin Business School Table of Contents Chapter 1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………. 1 1.1 Background and Rationale………………………………………………………………. 1 1.2 Aims and Objectives ……………………………………………………………………. 3 Chapter 2 Literature Review 2.1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………... 4 2.2 Jung and the Dream……………………………………………………………….…….. 4 2.3 Resistance to Jung….…………………………………………………………………… 6 2.4 The Analytic Process..………………………………………………………………….. 8 2.5 The Matter of Interpretation……...……………………………………………………..10 2.6 Individuation………………………………………………………………………….. 12 2.7 Freud and Jung…………………………………….…………………………………... 13 2.8 Decline of the Dream………………………………………………………..………… 15 2.9 Changing Paradigms……………………………………………………………....….. 17 2.10 Science, Spirituality, and the Dream………………………………………….………. 19 Chapter 3 Methodology…….……………………………………...…………………….. 23 3.1 Introduction to Approach…..………………………………………………………..... 23 3.2 Rationale for a Qualitative Approach..…………………………………………..……..23 3.3 Thematic Analysis..………………………………………………………………..….. 24 3.4 Sample and Recruitment...…………………………………………………………….. 24 3.5 Data Collection..………………………………………………………………………. 25 3.6 Data Analysis..………………………………………………………………………... 26 3.7 Ethical Issues……..……………………………………………………………….…... 27 Chapter 4 Research Findings…………………………………………………………… -

ATLANTA DREAM Vs NEW YORK LIBERTY May 14 Connecticut* L, 67-78 Twitter Atlanta, Ga

2021 REGULAR SEASON SCHEDULE Date Opponent Time (ET)/Result TV ATLANTA DREAM VS NEW YORK LIBERTY May 14 Connecticut* L, 67-78 Twitter Atlanta, Ga. • Gateway Center Arena @ College Park May 19 Chicago* L, 77-85 Facebook Tuesday, June 29 at 7:00 p.m. ET May 21 at Indiana* W, 83-79 Twitter Game 15 • Bally Sports Southeast/ESPN3 PxP: Angel Gray • Color: Tabitha Turner • Sideline: Shanteona Keys May 25 at Chicago* W, 90-83 CBSSN Explorer Explorer May 27 Dallas W, 101-95 BSSO May 29 at New York* W, 90-87 Prime Video June 4 at Minnesota L, 84-86 Facebook PROBABLE STARTERS June 6 at Minnesota L, 80-100 BSSE G #0 ODYSSEY SIMS 5-8 | 163 | Baylor June 9 Seattle L, 71-95 BSSE 2021: Led the team with 14 points in her Dream debut against Connecticut (5/14), adding on four June 11 Seattle L, 75-86 CBSSN rebounds, two assists and a steal ... Started and led the team with 6 assists at MIN (6/4) ... Season-best June 13 Washington* W, 101-78 BSSO/NBA TV performance against WAS (6/13) with 20 points, 4 steals and 5 rebounds ... Led the team outright in June 17 at Washington* L, 93-96 League Pass scoring for the first time with 22 points at Washington (6/17), season-high 7 assists with 3 steals. June 23 Minnesota L, 85-87 BSSE Alt G #10 COURTNEY WILLIAMS 5-8 | 133 | South Florida June 26 New York* L, 78-101 BSSO 2021: Double-digit scoring in 11 of the Dream’s 12 games so far this season .. -

ATLANTA DREAM (11-4) Vs. INDIANA FEVER (6-9) July 1, 2014 • 8:00 P.M

ATLANTA DREAM (11-4) vs. INDIANA FEVER (6-9) July 1, 2014 • 8:00 p.m. ET • TV: ESPN2 Philips Arena • Atlanta, Ga. Regular Season Game 16 • Home Game 9 2014 Schedule & Results PROBABLE STARTERS Date .........Opponent ....................Result/Time Pos. No. Player PPG RPG APG Notes May 11 ..... NEW YORK^ .......................W, 63-58 G 9 CELINE DUMERC 1.6 1.9 3.4 Made her first WNBA start Sunday May 16 ..... SAN ANTONIO (SPSO) ....W, 79-75 5-7 • 132 • France night at Indiana May 17 ..... at Indiana (FSS) .......W, 90-88 (2OT) Third in the league in 3-point field goal May 24 ..... at Chicago (NBA TV) .......... L, 73-87 11.0 3.1 1.9 G 15 TIFFANY HAYES pct. (.475) May 25 ..... INDIANA (SPSO) ...... L, 77-82 (OT) 5-10 • 155 • Connecticut May 30 ..... SEATTLE (SPSO) ................W, 80-69 G 35 ANGEL McCOUGHTRY 20.1 5.4 4.1 Averaging 23.2 points per game in her June 1 ....... at Connecticut ....................... L, 76-85 last five games June 3 ....... LOS ANGELES (ESPN2) ....W, 93-85 6-1 • 160 • Louisville June 7 ....... CHICAGO (SPSO) ..............W, 97-59 F 20 SANCHO LYTTLE 11.9 9.0 2.5 Tied for second in the league with six June 13 .... MINNESOTA (SPSO) .........W, 85-82 6-4 • 175 • Houton double-doubles this season June 15 .... at Washington ......................W, 75-67 June 18 .... WASHINGTON (FSS) ........W, 83-73 C 14 ERIKA DE SOUZA 15.7 9.7 1.4 Scored in double figures in every game June 20 .... NEW YORK (SPSO) ...........W, 85-64 6-5 • 190 • Brazil but one this season June 22 ... -

Assessing Dream Work: Conceptualizing Dream Work As an Intervention in Dream Life David Jenkins Private Practice, Berkeley, CA, USA

Assessing dream work I J o D R Assessing dream work: Conceptualizing dream work as an intervention in dream life David Jenkins Private Practice, Berkeley, CA, USA Summary. How can we gauge the effectiveness of dream work? The question is especially difficult when we try to encompass the various theories of dreams such as those of Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung and the many current forms of dream work. A rationale is offered for why this has proved so difficult. A schematic approach to depicting dream work is described that illuminates some of the issues and a novel approach to assessing dream work is offered. Typically, the measures used for effective dream work are self-assessments by the dreamer (e.g. DeCicco, 2007, Hill & Knox, 2010, Taylor, 1998, Ullman, 1994). A different approach is possible if we conceptualize dream work as an intervention in the dreamer’s dream life. The dream work can then be judged by its influence on the next dream. This is of value to the dream worker as it provides feedback that allows her to adjust her work. It has the benefit that it allows for an indepen- dent assessment rather than relying on the self-assessment of the dreamer. It is an approach that potentially offers a rigorous methodology without causing damage to the intent of the many varieties of dream work. Keywords: Interpretation, Assessment, Intervention, IRT, Montague Ullman, Jeremy Taylor, Aha moment, Barry Krakow Within dream work – i.e. the discussion, analysis or ex- the product of the dream work is usually not behavioral at pression of a dream to elicit a further understanding of the all. -

DREAM Challenges Advancing Our Understanding of Human Disease

DREAM Challenges Advancing our understanding of human disease through data-centric competitions Michael Kellen, PhD Director, Technology Platforms and Services Sage Bionetworks Crowd-sourcing in History Crowd-sourcing Today DREAM: What is it? A crowdsourcing effort that poses questions (Challenges) about systems biology modeling and data analysis: – Transcriptional networks, – Signaling networks, – Predictions to response to perturbations – Translational research DIALOGUE FOR REVERSE ENGINEERING ASSESSMENT AND METHODS DREAM: Structure of a Challenge Data Crowd- sourcing Measurements Predictions Ground Truth Unbiased Evaluation Acceleration of Research Collaboration The challenge improvement loop Incentives for participation • Partnerships with journal editors – “Challenge Assisted Peer Review” • Challenge webinars for live interaction between participants and organizers • Community forums where participants can learn from each other • Leaderboard to motivate continuous participation • Annual DREAM Conference to celebrate and discuss Challenge outcomes DREAM 7 Published April 2013 DREAM 8 Post-analysis and paper writing phase DREAM8.5 Challenges Open for Participation • Predict cancer-associated mutations from whole-genomc sequencing data • Opened Nov 8 • 172 registered participants • Predict which patients will not respond to anti-TNF therapy • Opens Feb 10 • 208 registered participants • Predict early AD-related cognitive decline, and the mismatch between high amyloid levels and cognitive decline • Dry run phase: opening in March • 161 registered participants DREAM 9 Challenges opening in May-June 2014 • Broad Gene Essentiality Challenge – Data Set: 500 cell lines with molecular characterization data (from CCLE) and gene essentiality data (from Achilles RNAi screens). – Challenge structure: Participants train gene essentiality predictive models using training data. Use molecular information from test data to predict gene essentiality scores, which are compared against held out dataset. -

COURSE SYLLABUS PSY270 Spring 2014

COURSE SYLLABUS PSY270 Spring 2014 WHAT’S IN THIS SYLLABUS COURSE DESCRIPTION & OBJECTIVES: Why is sleep so important? What you will learn? To be a peak performer you need to be fully By the end of this course, you will have a alert, dynamic, energetic, in a good mood, better understanding of… and cognitively sharp. You must be able to 1) The fundamental nature of sleep, includ- concentrate, remember, make critical and ing the distinction between REM (rapid RESOURCES AND POLICIES 2 creative decisions, communicate persua- eye movement) and NREM (non-rapid Got a question? Need help? sively, and be productive all eye movement sleep), developmen- Want clarification on course pol- tal changes in sleep patterns, sleep day long. None of this is icies? Check here first. possible without quality “When you have across species, etc. sleep. insomnia, 2) Theories of the function(s) ASSIGNMENTS & GRADING 3 you're never really served by both REM and NREM Guidelines and advice for making Furthermore, healthy sleep asleep, sleep. the most of the assignments, and has been proven to be the and you're never 3) Sleep disorders and their iden- really awake.” instructions for submitting your single most important de- ~From the movie Fight Club, tification. terminant in predicting lon- based on the novel by Chuck 4) Dreams and the differing views work. Palahniuk gevity. It is more influential on the significance and purpose of ASSIGNMENT CALENDAR 4-5 than diet, exercise or heredi- sleep-related mentation. Keep up to date and never be late ty, but our modern culture has become a 5) I hope this course will stimulate your STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES study in sleep deprivation. -

The American Dream

UNIT 1 The American Dream Visual Prompt: How does this image juxtapose the promise and the reality of the American Dream? Unit Overview In this unit you will explore a variety of American voices and define what it is to be an American. If asked to describe the essence and spirit of America, you would probably refer to the American Dream. First coined as a phrase in 1931, the phrase “the American Dream” characterizes the unique promise that America has offered immigrants and residents for nearly 400 years. People have come to this country for adventure, opportunity, freedom, © 2014 College Board. All rights reserved. and the chance to experience the particular qualities of the American landscape. Unit 1 • The American Dream 1 UNIT The American Dream 1 GOALS: Contents • To understand and define complex concepts such as Activities the American Dream 1.1 Previewing the Unit .................................................................... 4 • To identify and synthesize a variety of perspectives 1.2 Defining a Word, Idea, or Concept ............................................... 5 • To analyze and evaluate the Essay: “A Cause Greater Than Self,” by Senator John McCain effectiveness of arguments 1.3 America’s Promise ....................................................................... 8 • To analyze representative texts from the American Poetry: “The New Colossus,” by Emma Lazarus experience Speech: Excerpt from Address on the Occasion of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Statue of Liberty, by Franklin D. Roosevelt 1.4 America’s Voices ....................................................................... 12 ACADEMIC VOCABULARY primary source Poetry: “I Hear America Singing,” by Walt Whitman structure Poetry: “I, Too, Sing America,” by Langston Hughes defend Poetry: “America,” by Claude McKay challenge qualify 1.5 Fulfilling the Promise ...............................................................