FORD ML 2002.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lower Woodhouse Cottage, Thelbridge, Crediton, Devon, EX17 4SJ

Lower Woodhouse Cottage, Thelbridge, Crediton, Devon, EX17 4SJ A beautifully presented Grade II listed thatch cottage with charm and character set in Mid Devon. South Molton 11 miles - Tiverton 12 miles - Exeter 18 miles • 2 Double Bedrooms • Newly Fitted Kitchen/Dining Room • Sitting Room with Woodburner • Newly Fitted Shower Room • Downstairs WC & Utility • Workshop/Garage & Parking • Lovely Gardens • Rural Guide price £315,000 01884 235705 | [email protected] Cornwall | Devon | Somerset | Dorset | London stags.co.uk Lower Woodhouse Cottage, Thelbridge, Crediton, Devon, EX17 4SJ SITUATION markets. Lower Woodhouse Cottage lies in a wonderful rural location in mid Devon between the From Tiverton there is a dual carriageway to hamlets of Thelbridge and East Worlington with Junction 27 of the M5 motorway, nearby to easy access to the market towns of South which is Tiverton Parkway railway station. Molton and Tiverton. DESCRIPTION Lower Woodhouse Cottage is a beautifully At Thelbridge there is a church and a popular presented grade II listed detached cottage in public house whilst the village of Witheridge the heart of Mid Devon countryside. Over lies within two miles. Witheridge, with its Saxon recent years the property has undergone square and fine parish church, offers a good complete refurbishment and the current range of amenities including primary school, owners have improved greatly including a new health centre, veterinary practice, public house, kitchen and shower room, all new windows, village shop, post office and separate new plumbing and central heating system newsagents and village hall with tennis court. (outside Worcester combi-boiler). The cottage is well presented throughout and there are The market towns of South Molton and many character features including exposed Tiverton are within eleven and twelve miles beams and floorboards. -

Crediton Town Council

Crediton Town Council Page 11 Minutes of the Crediton Town Council Meeting, held on Tuesday, 21st June 2016, at 7pm, at the Council Chamber, Market Street, Crediton Present: Cllrs Mr F Letch (Chairman & Mayor), Miss J Harris, Mr A Wyer, Mrs H Sansom, Mr D Webb, Mr W Dixon, Miss J Walters, Mrs L Brookes-Hocking, Mr M Szabo and Mr N Way In Attendance: Mrs Clare Dalley, Town Clerk 1 member of the press 5 members of the public 1606/43 To receive and accept apologies DRAFTIt was resolved to receive and accept apologies from Cllrs Mr J Downes and Mrs A Hughes. (Proposed by Cllr Letch) 1606/44 Declarations of Interest Cllrs Letch and Way declared that as members of more than one authority, that any views or opinions expressed at this meeting would be provisional and would not prejudice any views expressed at a meeting of another authority. Cllr Letch declared a personal interest in agenda item 10 ‘Mid Devon District Council – Planning Applications’ and planning application numbered 16/00854/HOUSE as his property adjoins the applicant’s. Cllr Webb declared a personal interest in the following agenda items • 10 ‘Mid Devon District Council – Planning Applications’ and planning application numbered 16/00774/FULL as the applicant is a personal friend and business associate. • 13 ‘To consider a new premises licence application for 11-12 High Street, Crediton, Devon, EX17 3AE’ as the applicant is a personal friend. 1606/45 To receive a presentation from Mr Jonathan Tricker on Crediton Traffic Study – Full Report. The Clerk advised members that Mr Tricker had sent his apologies for the meeting and his presentation would be re-scheduled. -

Black's Guide to Devonshire

$PI|c>y » ^ EXETt R : STOI Lundrvl.^ I y. fCamelford x Ho Town 24j Tfe<n i/ lisbeard-- 9 5 =553 v 'Suuiland,ntjuUffl " < t,,, w;, #j A~ 15 g -- - •$3*^:y&« . Pui l,i<fkl-W>«? uoi- "'"/;< errtland I . V. ',,, {BabburomheBay 109 f ^Torquaylll • 4 TorBa,, x L > \ * Vj I N DEX MAP TO ACCOMPANY BLACKS GriDE T'i c Q V\ kk&et, ii £FC Sote . 77f/? numbers after the names refer to the page in GuidcBook where die- description is to be found.. Hack Edinburgh. BEQUEST OF REV. CANON SCADDING. D. D. TORONTO. 1901. BLACK'S GUIDE TO DEVONSHIRE. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/blacksguidetodevOOedin *&,* BLACK'S GUIDE TO DEVONSHIRE TENTH EDITION miti) fffaps an* Hlustrations ^ . P, EDINBURGH ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK 1879 CLUE INDEX TO THE CHIEF PLACES IN DEVONSHIRE. For General Index see Page 285. Axniinster, 160. Hfracombe, 152. Babbicombe, 109. Kent Hole, 113. Barnstaple, 209. Kingswear, 119. Berry Pomeroy, 269. Lydford, 226. Bideford, 147. Lynmouth, 155. Bridge-water, 277. Lynton, 156. Brixham, 115. Moreton Hampstead, 250. Buckfastleigh, 263. Xewton Abbot, 270. Bude Haven, 223. Okehampton, 203. Budleigh-Salterton, 170. Paignton, 114. Chudleigh, 268. Plymouth, 121. Cock's Tor, 248. Plympton, 143. Dartmoor, 242. Saltash, 142. Dartmouth, 117. Sidmouth, 99. Dart River, 116. Tamar, River, 273. ' Dawlish, 106. Taunton, 277. Devonport, 133. Tavistock, 230. Eddystone Lighthouse, 138. Tavy, 238. Exe, The, 190. Teignmouth, 107. Exeter, 173. Tiverton, 195. Exmoor Forest, 159. Torquay, 111. Exmouth, 101. Totnes, 260. Harewood House, 233. Ugbrooke, 10P. -

Friday 21St Store Stock Market

EXETER LIVESTOCK CENTRE MARKET REPORT June 2019 Friday 21st Store Stock Market EXETER LIVESTOCK CENTRE Matford Park Road, Exeter, Devon, EX2 8FD 01392 251261 [email protected] www.kivells.com Friday 21st June 355 STORE CATTLE, STIRKS & BEEF BREEDING STOCK – 10AM Auctioneer: Simon Alford 07789 980203 Steers to £1205 Heifers to £885 Friday saw store steers top at £1205 for a trio of strong ‘brindle’ Limousin steers (27m) from Ken Harris of Ivybridge whilst Beef Shorthorns were the order of the day making £1095 (18m) for Eddie Yeandle of Cheriton Fitzpaine and £1050 (26m) for Michael Tooze of Broadsands, the latter also seeing £1055 for a smart Charolais steer (26m). A pair of British Blue bullocks (24m) from Steve Baker of Kennford rose to £1050 apiece whilst Aberdeen Angus steers (21m) saw £950 for Basil Cane of Plymouth. Young steers of note included a cracking Limousin (only 14m) at a decent £970 for Alan Cook of Ivybridge and £885 for a couple of Blonde D’Aquitaine steers of a similar age from Martin Curtis of Plymouth. A tremendous run of store heifers from Bruce Ellett of Exmouth headed that section with a bunch of four well grown Charolais (22m) catching the eye and selling for £885 apiece closely followed by Bruce’s better pen of Salers heifers (23m) at £880 a life. A muscled South Devon heifer (25m) from Basil Cane looked good money at £870 as did a British Blue (19m) from Graham & Carol Northmore, Clyst Honiton at £835. Strong Blonde D’Aquitaine heifers (24m) from Ian Lethbridge, East Allington fetched £805 with neat later born types of the same breed seeing £865 for Martin Curtis again and a nicely shaped British Blue heifer (only 13m) took home £790 for Matt & Vicky smith of Thelbridge. -

William Webber (Note 1)

Webber Families originating in the Middle Section of the Taw Valley in the late 18th and 19th centuries, (mainly Chulmleigh, Chawleigh and Burrington, plus some neighbouring parishes with close links to them). Compiled by David Knapman © April 2014 To the reader: If you find something here which is of interest, you are welcome to quote from this document, or to make reasonable use of it for your own personal researches, but it would be appreciated if you would acknowledge the source where appropriate. Please be aware that this is a ‘live’ document, and is sure to contain mistakes. As and when I find or receive better information I will add to and/or correct it. This raises two points: if you find an error or omission, please let me know; and if you propose to use the information contained here at some future point, it may be worth checking back with me to see whether the information you propose to use has subsequently been corrected or improved. Although I do not generally propose to extend the narrative past 1900, I would be very pleased to attach a note to any of the families to report that a family of 21st century Webbers can be traced back to any of the families identified here. So if you find your ancestors, and the Webber surname survives via their / your family, please let me know. David Knapman, April 2014 (david.j.knapman @ btinternet.com) Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Families from Chulmleigh and Around 4 3 Families from Chawleigh 81 4 Families from Burrington 104 Chapter 1: Introduction Purpose and main sources The focus of this document is on the existence and survival of the Webber surname. -

The Local Government Boundary Commission for England Electoral Review of Mid Devon

SHEET 1, MAP 1 THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND ELECTORAL REVIEW OF MID DEVON Final recommendations for ward boundaries in the district of Mid Devon January 2021 Sheet 1 of 1 MOREBATH CP Boundary alignment and names shown on the mapping background may not be up to date. They may differ from the latest boundary information applied as part of this review. CLAYHANGER CP This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of the Keeper of Public Records © Crown copyright and database right. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and database right. The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2020. OAKFORD CP BAMPTON CP KEY TO PARISH WARDS CREDITON CP A BONIFACE CLARE & B LAWRENCE SHUTTERN HOCKWORTHY CP CULLOMPTON CP HUNTSHAM CP C PADBROOK STOODLEIGH CP HOLCOMBE D ST ANDREWS ROGUS CP E VALE TIVERTON CP CANONSLEIGH F CASTLE G COVE G H CRANMORE I LOWMAN WASHFIELD CP J WESTEXE UPLOWMAN CP SAMPFORD BURLESCOMBE CP TIVERTON PEVERELL CP LOWMAN LOXBEARE CP CULMSTOCK CP TEMPLETON CP I UPPER CLAYHIDON CP F CULM HEMYOCK CP TIVERTON THELBRIDGE CP TIVERTON WESTEXE CASTLE H TIVERTON CP J CHAWLEIGH CP CRUWYS TIVERTON HALBERTON CP UFFCULME CP WEMBWORTHY CP MORCHARD CP CRANMORE TAW VALE PUDDINGTON HALBERTON WASHFORD CP PYNE CP WILLAND CP LOWER WAY CULM EGGESFORD CP LAPFORD CP WOOLFARDISWORTHY CP KENTISBEARE CP POUGHILL CP CADELEIGH CP BUTTERLEIGH CP CULLOMPTON ST NYMET ANDREWS D BRUSHFORD CP ROWLAND CP C KENNERLEIGH CP MORCHARD BISHOP CP CULLOMPTON STOCKLEIGH -

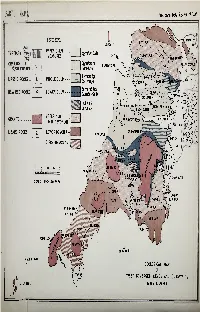

Ussher, W a E, the British Culm Measures, Part II, Volume 38

XXXVIII. VoL Soc. Archl Somt Proc. I. MAP I. PART XXXVlIf. Vol. Soc. ArcM Somt. Proc. SECTIONS. WITH II. MAP 11. PART L Cbe BritisJ) Culm ^easute0. BY W. A. E. USSHEK. By permission of the Director General of Her Majesty’’ s Geological Survey. PART L IN TKODUCTION. N a paper On the probable nature and distribution of the I Palasozoic strata beneath the Secondary rocks of the South Western Counties,” which appeared in the Proceedings of the Somersetshire Arch. & Nat. Hist. Soc. for 1890, the relations of the Devonshire Culm Measures were briefly discussed. In the present communication I propose to consider, specially, the Culm Measures of the South Western Counties ; amplifying in many important particulars the brief accounts published in the Geological Magazine for January, 1887, and discussing in a separate section the effects on the structure of the Culm Measures produced by the Granite. An admirable resume of the early literature of the Culm Measures will be found in Dr. H. Woodward’s invaluable paper. The general structure of the Culm Measures has long been knownf : it is admirably sketched in De la Beche’s section^ from Marsh, near Swimbridge, on the north, to Cawsand Beacon, Dartmoor, on the south, where the distribu- tion of the beds in a shallow synclinal, complicated by many lesser folds, is shown. The correspondence of the lower * Geol. Mag. for 1884, p. 534. t Sedgwick and Murchison Rep. Brit. Ass. Vol. 5, p. 95, 1836. Rev. D. Williams, Rep. Proc. Brit. Ass. Athenoeum, Oct. 7. 1837. J Rep. on. Geol. of Cornwall, Devon and Somerset, p. -

Devonshire. 979

TRADES DIRECTORY. J DEVONSHIRE. 979 Da.rby Loui~, Karswell, Hockworthy, Davey William, Longland: Cross, Claw- Dendle Wm. Yenn, Sandford, Crediton Wellington (Somerset) ton, Holsworthy Denford Thomas, North Heal, High Darch ~, Luscott Barton, Braunton Davey William, N'orth Betworthy, Bickington, Chulmleigh R.S.O Bucks mills, Bideford Denley Jn. Bickington, Newton .Abbot ])arch Henry, Mekombe, 1\Iarwood, Davie John J. Northleigh, Goodleigh, Denner William,Southdown, Salcombe Barnstaple Barnstaple Regis, Sidmouth })arch J ames, Horry mill, W emb Davie 1Vm. East Ashley, Wembworthy Denning William, Exeter rd.Cullomptn worthy R.S.O R.S.O Dennis Brothers, Harts, Lift-on R.iS.O J)arch John, Indicknowl, Combmar Davies Fredk. Thornton Kenn, Exeter Dennis Albert, Buddle, Broadwaod tin, llfracombe Davies G.Hoemore,Up-Ottery, Honiton Widger, Lifton R.S.O Darch Richard, Lugsland, Crnwys Davies Joseph, Stourton, Thelbridge, Dennis C.Sticklepath,Taw.stock,Brnstpl ::llorchard, Tiverton Morchard Bishop R.S.O Dennis ~iss Charlotte, West Worth, Darch W. High Warcombe,llfracombe Davies William, West Batsworthy,Cre- North Lew, Beaworthy R.S.O Darch William Henry, "\Vestacombe, ccmbe, M01·chard Bishop R.S.O Dennis EdwardMedland, Torhill,Drew- Swymbridge, Barnstaple Da;~·is Albert, Rockbeare, Exeter steigntDn, Newton Abbot Dare Fred. Kilmington, Axminster Davi,; Jame;;, Garramarsh, Queens- Denni.s Edrwin, Grinnicombe, iBroa.d- JJare George, Yetlands, Axminster nymptDn, South Moltolll >v-ood Widger, LiftDn R.S.O . JJ11re Waiter, Old Coryton, Kilming- Davis John, French Nut tree, Clay- Dennis Edwin, WoodLand. Ivybridge ton, Axminster hidon, Wellington (Somerset) Dennis F. Venton, Highampton R..S.O 1Jark Henry, 1Voodgates, Sourton, Davis ·w.Youn~hayes,Broadclyst,Exetr Dennis Frdk. -

The South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine, Began Its Career with the January Number

THE SOUTH C AROLINA HISTORICAL AND GENEALOGICAL M AGAZINE. PUBLISHED Q UARTERLY BY* » THE S OUTH CAROLINA HISTORICAL SOCIETY CHARLESTON, S. C. EDITEDY B A.. S SALLEY, JR., SECRETARY A ND TREASURER OF THE SOCIETY. VOLUME I . Printed f or the Society by THE WALKER. EVANS A COOSWELL CO., Charleston, S. C. I900. OFFICERS OFHE T South C arolina Historical Society President, G en. Edward MoCbady. 1st V ice-President, Hon. Joseph W. Barnwell. 2nd V ice-President, Col. Zimmerman Davis. Secretary a nd Treasurer and Librarian, A.. S Salley) Jr. Curators : Lang d on Cheves, Henry. A M. Smith, D. E. Huger Smith, Theodore D. Jervey, S. Prioleau Ravenel, Thomas della Torre. Charles. W Kollock, M. D. Boardf o Managers. All of the foregoing officers. Publication C ommittee. Joseph W. Barnwell, Henry A. M. Smith. A.. S Salley, Jr. THE SOUTH C AROLINA HISTORICAL AND GENEALOGICAL M AGAZINE PUBLISHED Q UARTERLY BY THE SOUTH C AROLINA HISTORICAL SOCIETY, CHARLESTON, S. C. VOL-— I No. 1. JANUARY, 10OO- Printed l or the Society by THE WALKER. EVAN5 & COOS WELL CO., Charleston, S. C. CONTENTS Letter f rom Thomas Jefferson to Judge William Johnson 3 The M ission of Col. John Laurens to Europe in 1781 ... 13 Papersf o the First Council of Safety ±1 The B ull Family of South Carolina 76 Book R eviews and Notes 91 Notes a nd Queries 98 The S outh Carolina Historical Society 107 N.. B The price of a single number of this Magazine is one d ollar to any one other than a member of the South Carolina H istorical Society. -

64 Ford 491 Gratton House, William Lane

LIST OF THE PRINCIPAL SEATS IN DEVONSHIRE. xv PAGE PAGE «jombe Fishacre bouse, Thomas Hodgson Archer-Hind Exeter palace, The Lord Bishop of Exeter (Right Rev. esq. M.A., J.P. see Ipplepen 275 Edward Henry Bickersteth D.D.), see Exeter .••..•..• 165 .(jombe head, Major William Leir J. P. see Bampton .•..•• 37 Fairfield lodge, Alexander HenryAbercromby Hamilton Combe Royal, Mrs. Eady-Borlase & Miss Turner, see esq. J.P. see Countess Wear .................•..........•.... 128 Alvington West; _................... 21 Fallapit, William CubiU esq. J.P. see East Allington ••• 20 .connibere, Mrs. Babington, see Northam 331 Farringdon house, Edward Johnson esg. J.P. see Coombe, George Cutcliffe esq. J.P. see Witheridge ..•... 617 Farringdon ~..... 236 -Cornborough, Mrs. Vidal, see Abbotsham .....•....••..•..• I9 Flete, Hy. Bingham Mildmay esq. D. L., J.P. see Holbeton 252 -Coryton park, Rev. Marwood Tucker, see Kilmington.•• 281 Follaton house, Stanley Edward George Caryesq. J.P. Cotlands, Thomas Kennet-Were esq. J.P. see Sidmouth 517 see Totnes............... 595 -Court barn, Mrs. Melhuish, see Clawton ••........••.••... 1I2 Ford, John Ponsford esg. J.P. see Drewsteignton •.•.•..•• 157 'Court hall, Mrs. Gard, see Monkton •.•..•.•..•• •••..•..•... 320 Fordehouse, Wm. In. Wattsesg. J.P. see Newton Abbot 326 .court hall, Lord Poltimore P.C., D.L., J.P. see North Fort hill, John Roberts Chanter esq. see Barnstaple ..• 43 Molwn 314 Fremington house, Miss Yeo, see Fremington 238 Conrtenay house, Charles Robert Collina esq. J.P. see Fursdon, Rev. Edward Fnrsdon M.A. see Cadbury ..•... 99 Teignmouth ~.. ... 548 Gaddon house, William Talley Wood esg. see Uffculme 601 Courtisknowl, Rev. Henry Geo. Hare B.A. see Diptford 153 Gateombe house, David Wise Bain esq. -

A Rural Rant Francis Fulford Tom Parker Bowles Edible

Issue No. 8 THE LIFE OF FRANK SINATRA JONATHAN WINGATE A RURAL RANT HOW AMERICA CREATED TRUMP FRANCIS FULFORD BRUCE ANDERSON TOM PARKER BOWLES UNDER STARTERS’ ORDERS EDIBLE PURITANISM HARRY HERBERT A HISTORY LESSON WITH SHOOTING ETIQUETTE BERNARD CORNWELL JONATHAN YOUNG MODERN MANNERS! WILLIAM SITWELL £4.95 $7.40 €6.70 ¥880 Autumn 2016 BOISDALELIFE.COM Issue no.7 == Order Remarks == == Pool Remarks == == Techspec == Filefromat: PDFx1a max. Size: TechSpec Infos: TechSpecFiles: LEGENDS ARE FOREVER HERITAGE I PILOT Ton-Up www.zenith-watches.com 3 Zenith_HQ • Visual: U21_PT3 • Magazine: Boisdale (UK) • Language: English • Issue: 26/10/2016 • Doc size: 420 x 297 mm • Calitho #: 10-16-118827 • AOS #: ZEN_12223 • OP 21/10/2016 Autumn 2016 BOISDALELIFE.COM Issue no.7 5 Autumn 2016 BOISDALELIFE.COM Issue no.7 NOW Boisdale of Mayfair 12 North Row London W1K 7DF 7 BoisdaleComingSoonDPSV3NowOpens.indd All Pages 09/11/2016 15:56 Autumn 2016 BOISDALELIFE.COM Issue no.7 EDITOR’S LETTER Your nest egg could GREAT EXPECTATIONS o the age of Trump has begun. “It is somewhat paradoxical that in the 21st perfect for a relaxing comfortable meal was the best of times, it was the century ideological orthodoxy seems to be or even a lovely indoor picnic! Whilst become a valuable source of worst of times, it was the age of the greatest enemy of civilization, having the restaurant boasts all the Boisdale wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it been the principal cause of its creation. classics, the very best Aberdeenshire dry was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch Perhaps what we need is pragmatic non- aged beef, stunning Hebridean shellfish, income Profits. -

DSM Dateline

The view from Down St Mary 780 to 2014 DSM timeline © Roger Steer 780 The Saxons reach the Tamar. During the period of the Saxons, the natural forests of Devon are gradually cleared and most of the villages and settlements we take for granted in the countryside are established. 905 Bishop Putta is murdered – some say at the spot where Copplestone cross stands. 909 Diocese of Crediton created. 934-53 Bishop Ethelgar collects funds for the building of St Mary’s Minster at Crediton. 974 Copplestone Cross, at the junction of Down St Mary with two other parishes until 1992, is mentioned in a charter, but is much older than that. It is early Celtic interlaced work such as is not found elsewhere in England except in Northumbria. The cross gives a name to a once noted Devon family which comes in the local rhyme: Crocker, Cruwys, and Coplestone, When the Conqueror came were found at home. Eleventh Century 1018 Buckfast Abbey is founded under the patronage of King Canute. 1040 The Manor of Down(e) named after the Saxon settlement DUN meaning Hill, first recorded as being the gift of King Harthacnut. (Harthacnut was king of Denmark from 1028 to 1042 and of England from 1040 to 1042. Some of the glebe land in the manor originally formed part of the Devon estates of Harthacnut’s father, Canute, king of England 1016-35.) Tenure is granted to Aelfwein, Abbot of Buckfast in support of the ministry of the Abbey Church. Down St Mary is one of six Devon churches held by the Abbot of Buckfast prior to the Norman conquest, the others being Churchstow, Petrockstow, South Brent, Trusham and Zeal Monachorum.