1 Tropical Cyclone Report Hurricane Sandy (AL182012) 22

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bob Was a Shoo-Shoo

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard Bob Was a Shoo-Shoo Every boy that grew up in New Orleans (at least in my age group) that managed to get himself into the least bit of mischief knows that the local expression for a firecracker that doesn’t go off is a “shoo-shoo”. It means a dud, something that may have started off hot, but ended in a fizzle. It just didn’t live up to its expectations. It could also be used to describe other things that didn’t deliver the desired wallop, such as an over-promoted “hot date” or even a tropical storm that (fortunately) wasn’t as damaging as its forecast. Back in 1968, I thought for a moment that I was that “dud” date, but was informed by the young lady I was escorting that she had called me something entirely different. “Chou chou” (pronounced exactly like shoo-shoo) was a reduplicative French term of endearment, meaning “my little cabbage”. Being a “petite” healthy leafy vegetable was somehow a lot better than being a non-performing firecracker. At least I wasn’t the only one. In 2009 the Daily Mail reported on a “hugely embarrassing video” in which Carla Bruni called Nicolas Sarkozy my ‘chou chou’ and “caused a sensation across France”. Bruni and Sarkozy: no “shoo-shoo” here The glamourous former model turned pop singer planted a passionate kiss on the French President and then whispered “‘Bon courage, chou chou’, which means ‘Be brave, my little darling’.” The paper explained, “A ‘chou’ is a cabbage in French, though when used twice in a row becomes a term of affection between young lovers meaning ‘little darling’.” I even noticed in the recent French movie “Populaire” that the male lead called his rapid-typing secretary and love interest “chou”, which somehow became “pumpkin” in the subtitles. -

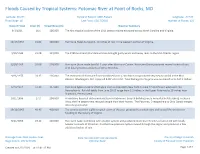

Floods Caused by Tropical Systems: Potomac River at Point of Rocks, MD

Floods Caused by Tropical Systems: Potomac River at Point of Rocks, MD Latitude: 39.274 Period of Record: 1889-Present Longitude: -77.543 Flood Stage: 16 Last Flood: 12/17/2018 Number of Floods: 121 Date of Flood Crest (ft) Streamflow (cfs) Weather Summary 9/1/1911 16.1 106,000 The first tropical cyclone of the 1911 season moved eastward across North Carolina and Virginia. 10/17/1954 21.02 130,000 Hurricane Hazel dumped 6- 10 inches of rain in the western portion of Virginia. 9/20/1945 21.98 139,000 The 1945 Southeast Florida Hurricane brought gusty winds and heavy rains to the Mid-Atlantic region. 8/20/1955 29.08 214,000 Hurricane Diane made landfall 5 days after Hurricane Connie. Hurricane Diane produced several inches of rain with locally heavier amounts of 10 to 20 inches. 9/26/1975 24.35 126,000 The remnants of Hurricane Eloise combined with a cold front and produced very heavy rainfall in the Mid- Atlantic. Washington, D.C. reported 9.08" of rainfall. Total damage for Virginia was estimated to be $17.2 million. 6/23/1972 37.43 347,000 Hurricane Agnes made landfall again over southeastern New York on June 22 and moved westward into Pennsylvania. Rainfall totals from June 20-25 range from 2-3 inches in the Upper Potomac to 18 inches near Shamokin, Pennsylvania. 10/1/1896 27.2 204,000 A hurricane knocked out communication in Richmond. Several buildings were unroofed in Petersburg. In Buena Vista, the fire department rescued people from their homes. -

FEMA FOIA Log – 2018

Mirandra Abrams, Monique any and all records concerning clients. Kindly provide our office with 10/4/2017 Sambursky a complete copy of clients entire file as it pertains as it pertains to Slone Sklarin Inquiry Number (b) (6) ; Voucher Number (b) (6) ; Payee Verveniotis Reference Number (b) (6) in your possession. 2017-FEFO-02138 - Masters, Mark all contract documents related to temporary staffing services 10/5/2017 contracts for emergency call center support for FEMA in the last five 2017-FEFO-02177 (5) years 2017-FEFO-02187 - (b) (6) all files, correspondence, or other records concerning yourself 10/6/2017 Dallas News Benning, Tom 1) All active FEMA contracts for manufactured housing units. 2) All 10/13/2017 active FEMA individual assistance/technical assistance contracts (IATACs). 3) All pre-event contracts for debris removal that are overseen by FEMA Region 6. 4) All pre-event contracts for housing assistance that are overseen by FEMA Region 6. 5) All noncompetitive disaster relief contracts approved by FEMA since August 14, 2017. 6) All non-local disaster relief contracts approved by FEMA since August 14, 2017, including the written justification 2017-FEFO-02214 for choosing a non-local vendor. FCI Keys, Clay a copy of any and all records related to [FEMA's] response to 10/23/2017 SEAGOVILLE hurricane Katrina, including all memoranda, communications and records of any kind and from any source from August 29, 2005 to 2012. (Date Range for Record Search: From 8/29/2005 To 2017-FEFO-02239 12/1/2012) - (b) (6) Any files related to yourself (Date Range for Record Search: From 10/24/2017 2017-FEFO-02240 1/1/2000 To 9/11/2017) - McClain, Don every individual who has requested assistance by FEMA from both 10/31/2017 Hurricane Irma and Harvey. -

Appendix A-Water Quality-Town Of

Appendix A Water Quality – Town of Greenwich Town of Greenwich Drainage Manual February 2012 [This page left intentionally blank] Impaired Water Bodies – Town of Greenwich Water Body Impaired Segment Location Cause Potential Source Segment Designated Use Size From mouth at Greenwich Harbor (just downstream [DS] of I95 crossing, at exit Habitat for Fish, Horseneck 5.78 3 offramp), US to Putnam Lake Other Aquatic Cause Unknown Source Unknown Brook-01 Miles Reservoir outlet dam (just upstream [US] Life and Wildlife of Dewart Road crossing) From head of tide (US of Route 1 Habitat for Fish, Sources Outside State Jurisdiction or Borders, Source crossing, at INLET to ponded portion of Other Aquatic Cause Unknown Unknown, Highway/Road/Bridge Runoff (Non- Byram River- river, just DS of Upland Street East 0.49 Life and Wildlife construction Related) 01 area), US to Pemberwick outlet dam (US Miles Illicit Connections/Hook-ups to Storm Sewers, Source of Comly Avenue crossing, and US of Recreation Escherichia coli Unknown confluence with Pemberwick Brook Putnam Lake Habitat for Fish, Impoundment of Horseneck Brook, just 95.56 Alterations in wetland Reservoir Other Aquatic Habitat Modification - other than Hydromodification south of Rt. 15 Acres habitats (Greenwich) Life and Wildlife Western portion of LIS, Inner Estuary, Dissolved oxygen LIS WB Inner - upper Indian Harbor (lower portion of Habitat for 0.025 saturation; Nutrient/ Residential Districts, Municipal Point Source Indian Harbor Greenwich Creek) from Davis Avenue Marine Fish, Square Eutrophication Discharges, Non-Point Source, Unspecified Urban (upper), crossing, US to saltwater limit at West Other Aquatic Miles Biological Indicators; Stormwater Greenwich Brother Drive crossing (includes I95 Life and Wildlife Oxygen, Dissolved crossing). -

Get Charmed in Charm City - Baltimore! "…The Coolest City on the East Coast"* Post‐Convention July 14‐17, 2018

CACI’s annual Convention July 8‐14, 2018 Get Charmed in Charm City - Baltimore! "…the Coolest City on the East Coast"* Post‐Convention July 14‐17, 2018 *As published by Travel+Leisure, www.travelandleisure.com, July 26, 2017. Panorama of the Baltimore Harbor Baltimore has 66 National Register Historic Districts and 33 local historic districts. Over 65,000 properties in Baltimore are designated historic buildings in the National Register of Historic Places, more than any other U.S. city. Baltimore - first Catholic Diocese (1789) and Archdiocese (1808) in the United States, with the first Bishop (and Archbishop) John Carroll; the first seminary (1791 – St Mary’s Seminary) and Cathedral (begun in 1806, and now known as the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary - a National Historic Landmark). O! Say can you see… Home of Fort McHenry and the Star Spangled Banner A monumental city - more public statues and monuments per capita than any other city in the country Harborplace – Crabs - National Aquarium – Maryland Science Center – Theater, Arts, Museums Birthplace of Edgar Allan Poe, Babe Ruth – Orioles baseball Our hotel is the Hyatt Regency Baltimore Inner Harbor For exploring Charm City, you couldn’t find a better location than the Hyatt Regency Baltimore Inner Harbor. A stone’s throw from the water, it gets high points for its proximity to the sights, a rooftop pool and spacious rooms. The 14- story glass façade is one of the most eye-catching in the area. The breathtaking lobby has a tilted wall of windows letting in the sunlight. -

Hurricane and Tropical Storm

State of New Jersey 2014 Hazard Mitigation Plan Section 5. Risk Assessment 5.8 Hurricane and Tropical Storm 2014 Plan Update Changes The 2014 Plan Update includes tropical storms, hurricanes and storm surge in this hazard profile. In the 2011 HMP, storm surge was included in the flood hazard. The hazard profile has been significantly enhanced to include a detailed hazard description, location, extent, previous occurrences, probability of future occurrence, severity, warning time and secondary impacts. New and updated data and figures from ONJSC are incorporated. New and updated figures from other federal and state agencies are incorporated. Potential change in climate and its impacts on the flood hazard are discussed. The vulnerability assessment now directly follows the hazard profile. An exposure analysis of the population, general building stock, State-owned and leased buildings, critical facilities and infrastructure was conducted using best available SLOSH and storm surge data. Environmental impacts is a new subsection. 5.8.1 Profile Hazard Description A tropical cyclone is a rotating, organized system of clouds and thunderstorms that originates over tropical or sub-tropical waters and has a closed low-level circulation. Tropical depressions, tropical storms, and hurricanes are all considered tropical cyclones. These storms rotate counterclockwise in the northern hemisphere around the center and are accompanied by heavy rain and strong winds (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA] 2013a). Almost all tropical storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic basin (which includes the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea) form between June 1 and November 30 (hurricane season). August and September are peak months for hurricane development. -

CONNECTICUT TERCENTENARY BULLETIN No

State of Connecticut Tercentenary Commission 1635-1935 Hartford, Conn. CONNECTICUT TERCENTENARY BULLETIN No. 10 June 17, 1935 TERCENTENARY FURNITURE A visitor to the exhibit, entering the west end of the Tapestry Hall, will find in the first section transition pieces, EXHIBITION OPENS AT corner cuboards, tip tables and highboys made of pine, MORGAN MEMORIAL cherry and maple. The first alcove, or room in the center partitioning of the Hall, finished in pink, holds a collection of Queen Anne period pieces. The second room, painted a One thousand and one pieces of the furniture and the buff color, is given over to furniture showing the transition furnishings which were part of the domestic life of Con- from European influence to the characteristic American necticut in Colonial times and the days of early statehood "Block Front" design, including some Hepplewhite. are now on display at the Morgan Memorial in Hartford The third, or green alcove, holds examples of the work forming one of the most complete ex- of Aaron Chapin, including highboys. hibitions of this character ever arranged. The last of the center partitions, done Selected from the wealth of material in a shade of yellow, shows late pieces, the people of Connecticut have pre- high-top and low desks, and a drop served of the fine things of their an- leaf table set with four chairs. cestors every article is a "museum Along the side platforms are arranged, piece". Almost any one or any group spaced as nearly as possible to coincide of the many period-collections is worthy with the period grouping in the center of a special showing. -

Meteorologia

MINISTÉRIO DA DEFESA COMANDO DA AERONÁUTICA METEOROLOGIA ICA 105-1 DIVULGAÇÃO DE INFORMAÇÕES METEOROLÓGICAS 2006 MINISTÉRIO DA DEFESA COMANDO DA AERONÁUTICA DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO METEOROLOGIA ICA 105-1 DIVULGAÇÃO DE INFORMAÇÕES METEOROLÓGICAS 2006 MINISTÉRIO DA DEFESA COMANDO DA AERONÁUTICA DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO PORTARIA DECEA N° 15/SDOP, DE 25 DE JULHO DE 2006. Aprova a reedição da Instrução sobre Divulgação de Informações Meteorológicas. O CHEFE DO SUBDEPARTAMENTO DE OPERAÇÕES DO DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO, no uso das atribuições que lhe confere o Artigo 1°, inciso IV, da Portaria DECEA n°136-T/DGCEA, de 28 de novembro de 2005, RESOLVE: Art. 1o Aprovar a reedição da ICA 105-1 “Divulgação de Informações Meteorológicas”, que com esta baixa. Art. 2o Esta Instrução entra em vigor em 1º de setembro de 2006. Art. 3o Revoga-se a Portaria DECEA nº 131/SDOP, de 1º de julho de 2003, publicada no Boletim Interno do DECEA nº 124, de 08 de julho de 2003. (a) Brig Ar RICARDO DA SILVA SERVAN Chefe do Subdepartamento de Operações do DECEA (Publicada no BCA nº 146, de 07 de agosto de 2006) MINISTÉRIO DA DEFESA COMANDO DA AERONÁUTICA DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO PORTARIA DECEA N° 33 /SDOP, DE 13 DE SETEMBRO DE 2007. Aprova a edição da emenda à Instrução sobre Divulgação de Informações Meteorológicas. O CHEFE DO SUBDEPARTAMENTO DE OPERAÇÕES DO DEPARTAMENTO DE CONTROLE DO ESPAÇO AÉREO, no uso das atribuições que lhe confere o Artigo 1°, alínea g, da Portaria DECEA n°34-T/DGCEA, de 15 de março de 2007, RESOLVE: Art. -

Port Recovery in the Aftermath of Hurricane Sandy VOICES Improving Port Resiliency in the Era of Climate Change from the FIELD

AUGUST 2014 Port Recovery in the Aftermath of Hurricane Sandy VOICES Improving Port Resiliency in the Era of Climate Change FROM THE FIELD By Commander Linda A. Sturgis, USCG; Dr. Tiffany C. Smythe and Captain Andrew E. Tucci, USCG Acknowledgements The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the New York and New Jersey Port community, first responders and dedicated volun- teers who selflessly helped so many people and saved numerous lives in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy. Dr. Smythe’s research on Hurricane Sandy was supported in part through the University of Colorado Natural Hazards Center’s Quick Response Grant Program, funded by National Science Foundation grant CMMI 1030670. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not represent the official policy or position of the Department of Defense, Department of Homeland Security or the U.S. government. Cover Image The U.S. Coast Guard fuel pier and shore side facilities in Bayonne, New Jersey were severely damaged from Hurricane Sandy’s storm surge. (U.S. COAST GUARD) AUGUST 2014 Port Recovery in the Aftermath of Hurricane Sandy Improving Port Resiliency in the Era of Climate Change By Commander Linda A. Sturgis, USCG; Dr. Tiffany C. Smythe and Captain Andrew E. Tucci, USCG About the Authors Commander Linda A. Sturgis is a Senior Military Fellow at Captain Andrew E. Tucci is the Chief of the Office the Center for a New American Security. She led the Hurricane of Port and Facility Compliance at Coast Guard Sandy port recovery effort during her assignment at Coast Headquarters in Washington DC. -

Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Strategy

Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force HURRICANE SANDY REBUILDING STRATEGY Stronger Communities, A Resilient Region August 2013 HURRICANE SANDY REBUILDING STRATEGY Stronger Communities, A Resilient Region Presented to the President of the United States August 2013 Front and Back Cover (Background Photo) Credits: (Front Cover) Hurricane Sandy Approach - NOAA/NASA (Back Cover) Hurricane Sandy Approach - NOAA/NASA Cover (4-Photo Banner) Credits - Left to Right: Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey - FEMA/ Rosanna Arias Liberty Island, New York - FEMA/Kenneth Wilsey Seaside Heights, New Jersey - FEMA/Sharon Karr Seaside Park, New Jersey - FEMA/Rosanna Arias Hurricane Sandy Letter from the Chair Rebuilding Strategy LETTER FROM THE CHAIR Last October, Hurricane Sandy struck the East Coast with incredible power and fury, wreaking havoc in communities across the region. Entire neighborhoods were flooded. Families lost their homes. Businesses were destroyed. Infrastructure was torn apart. After all the damage was done, it was clear that the region faced a long, hard road back. That is why President Obama pledged to work with local partners every step of the way to help affected communities rebuild and recover. In recent years, the Federal Government has made great strides in preparing for and responding to natural disasters. In the case of Sandy, we had vast resources in place before the storm struck, allowing us to quickly organize a massive, multi-agency, multi-state, coordinated response. To ensure a full recovery, the President joined with State and local leaders to fight for a $50 billion relief package. The Task Force and the entire Obama Administration has worked tirelessly to ensure that these funds are getting to those who need them most – and quickly. -

Six Flags Great Adventure Opens Most Significant Addition in Park's History

Q&A WITH SEAWORLD’S JIM ATCHISON — PAGES 40-41 AIMS NEWS & NOTES — PAGE 42 © TM Your Amusement Industry NEWS Leader! Vol. 17 • Issue 4 JULY 2013 INSIDE Six Flags Over Texas debuts Six Flags Great Adventure record setting Texas SkyScreamer...Page 9 opens most significant addition in park’s history STORY: Pam Sherborne [email protected] JACKSON, N.J. — Sa- fari Off Road Adventure, Six Flags Great Adventure’s tra- ditional Wild Safari attraction revamped, remade and revi- talized, became totally less traditional for the 2013 season and response, according to Six Flag officials, has been tre- mendous since opening May AT/GARY SLADE 24. SeaWorld Orlando unveils long awaited Six Flags doesn’t release monetary figures but Kris- Antarctica Empire of the Penguin...Page 14 tin Siebeneicher, Six Flags Giraffes are just one of the 1,200 animals guests taking the spokesperson, said this is the new Safari attraction may see. The Safari Off Road Adven- most significant improvement ture is included in admission into the park, but to feed the to this New Jersey park in its giraffes in Camp Aventura costs a little extra. 40-year history. COURTESY SIX FLAGS GREAT ADVENTURE The new 350-acre attrac- tion left its Wild Safari old for- mat — more of a ride-through Safari-themed section — to a totally new format where pa- trons are driven in a giant Sa- fari truck with a truck guide. The ability to take guests off-road and right up to the animals, along with personal guides, has offered an expe- rience totally unique to Six Flags Great Adventure. -

Columbus Day Parade Sunday by Michael P

Vol 21 Issue 39 • 20 Pages News and Views By and For West Haven • October 5, 2017 PRICELESS Columbus Day Parade Sunday By Michael P. Walsh Special to the Voice For the first time since 2011, the Greater New Haven Colum- bus Day Parade sails into the shore of West Haven’s deep-rooted Italian-American community at 1 p.m. Sunday with the largest procession of its kind in New England, featuring 80 marching units and 25 bands. The city takes over the Columbus Day Committee of Greater New Haven’s rotating parade from last year’s host, Hamden, assuming site duties for the annual procession that celebrates the intrepid spirit of Christopher Columbus, the Italian naviga- tor who discovered the New World 525 years ago and charted a course for millions of Italian sons and daughters who followed his crossing to America. “The journey of Christopher Columbus is one of the great sto- ries of daring and discovery, just as the journey of Italian im- Photos by Russ McCreven migrants is a story of discovery and bravery,” said Mayor Ed- ward M. O’Brien, whose Italian roots run on his mother’s side of the family. “As we embark on our city’s third parade in Co- lumbus’ name, let us commemorate his indomitable legacy and recognize the inspiring contributions of the Italian people to the Festival fun! heartbeat of our nation.” The West Haven Apple Fes- More than 15 million Americans claim Italian heritage, includ- tival, sponsored by the par- ing about 40 percent of West Haven’s residents, O’Brien esti- ish of First Church of Christ, mated.