The FCC's New Theory of the First Amendment, 51 Santa Clara L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Time-Varying Interactions Between Geopolitical Risks and Renewable Energy Consumption

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Cai, Yifei; Wu, Yanrui Working Paper Time-varying interactions between geopolitical risks and renewable energy consumption ADBI Working Paper Series, No. 1089 Provided in Cooperation with: Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), Tokyo Suggested Citation: Cai, Yifei; Wu, Yanrui (2020) : Time-varying interactions between geopolitical risks and renewable energy consumption, ADBI Working Paper Series, No. 1089, Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), Tokyo This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/238446 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/igo/ www.econstor.eu ADBI Working Paper Series TIME-VARYING INTERACTIONS BETWEEN GEOPOLITICAL RISKS AND RENEWABLE ENERGY CONSUMPTION Yifei Cai and Yanrui Wu No. -

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BTCCT-20061212AVR Communications, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CCF, et al. (Transferors) ) BTCH-20061212BYE, et al. and ) BTCH-20061212BZT, et al. Shareholders of Thomas H. Lee ) BTC-20061212BXW, et al. Equity Fund VI, L.P., ) BTCTVL-20061212CDD Bain Capital (CC) IX, L.P., ) BTCH-20061212AET, et al. and BT Triple Crown Capital ) BTC-20061212BNM, et al. Holdings III, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CDE, et al. (Transferees) ) BTCCT-20061212CEI, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212CEO For Consent to Transfers of Control of ) BTCH-20061212AVS, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212BFW, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting – Fresno, LLC ) BTC-20061212CEP, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting Operations, LLC; ) BTCH-20061212CFF, et al. AMFM Broadcasting Licenses, LLC; ) BTCH-20070619AKF AMFM Radio Licenses, LLC; ) AMFM Texas Licenses Limited Partnership; ) Bel Meade Broadcasting Company, Inc. ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; ) CC Licenses, LLC; CCB Texas Licenses, L.P.; ) Central NY News, Inc.; Citicasters Co.; ) Citicasters Licenses, L.P.; Clear Channel ) Broadcasting Licenses, Inc.; ) Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; and Jacor ) Broadcasting of Colorado, Inc. ) ) and ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BAL-20070619ABU, et al. Communications, Inc. (Assignors) ) BALH-20070619AKA, et al. and ) BALH-20070619AEY, et al. Aloha Station Trust, LLC, as Trustee ) BAL-20070619AHH, et al. (Assignee) ) BALH-20070619ACB, et al. ) BALH-20070619AIT, et al. For Consent to Assignment of Licenses of ) BALH-20070627ACN ) BALH-20070627ACO, et al. Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; ) BAL-20070906ADP CC Licenses, LLC; AMFM Radio ) BALH-20070906ADQ Licenses, LLC; Citicasters Licenses, LP; ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; and ) Clear Channel Broadcasting Licenses, Inc. ) Federal Communications Commission ERRATUM Released: January 30, 2008 By the Media Bureau: On January 24, 2008, the Commission released a Memorandum Opinion and Order(MO&O),FCC 08-3, in the above-captioned proceeding. -

Sex and Shock Jocks: an Analysis of the Howard Stern and Bob & Tom Shows Lawrence Soley Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette College of Communication Faculty Research and Communication, College of Publications 11-1-2007 Sex and Shock Jocks: An Analysis of the Howard Stern and Bob & Tom Shows Lawrence Soley Marquette University, [email protected] Accepted version. Journal of Promotion Management, Vol. 13, No. 1/2 (November 2007): 73-91. DOI. © 2007 Taylor & Francis (Routledge). Used with permission. NOT THE PUBLISHED VERSION; this is the author’s final, peer-reviewed manuscript. The published version may be accessed by following the link in the citation at the bottom of the page. Sex and Shock Jocks: An Analysis of the Howard Stern and Bob & Tom Shows Lawrence Soley Diederich College of Communication, Marquette University Milwaukee, WI Abstract: Studies of mass media show that sexual content has increased during the past three decades and is now commonplace. Research studies have examined the sexual content of many media, but not talk radio. A subcategory of talk radio, called “shock jock” radio, has been repeatedly accused of being indecent and sexually explicit. This study fills in this gap in the literature by presenting a short history and an exploratory content analysis of shock jock radio. The content analysis compares the sexual discussions of two radio talk shows: Infinity’s Howard Stern Show and Clear Channel’s Bob & Tom Show. Introduction The quantity and explicitness of sexual content in mass media has steadily increased during the past three decades. Greenberg and Busselle (1996) found that sexual activities depicted in soap operas increased between 1985 and 1994, rising from 3.67 actions per hour in 1985 to 6.64 per hour in 1994. -

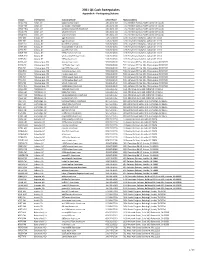

2021 Q1 Cash Sweepstakes Appendix a - Participating Stations

2021 Q1 Cash Sweepstakes Appendix A - Participating Stations Station iHM Market Station Website Office Phone Mailing Address WHLO-AM Akron, OH 640whlo.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-FM Akron, OH sunny1017.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-HD2 Akron, OH cantonsnewcountry.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WKDD-FM Akron, OH wkdd.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WRQK-FM Akron, OH wrqk.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WGY-AM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WGY-FM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WKKF-FM Albany, NY kiss1023.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WOFX-AM Albany, NY foxsports980.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WPYX-FM Albany, NY pyx106.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-FM Albany, NY 995theriver.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-HD2 Albany, NY wildcountry999.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WTRY-FM Albany, NY 983try.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 KABQ-AM Albuquerque, NM abqtalk.iheart.com 505-830-6400 5411 Jefferson NE, Ste 100, Albuquerque, NM 87109 KABQ-FM Albuquerque, NM 1047kabq.iheart.com 505-830-6400 5411 Jefferson NE, Ste 100, Albuquerque, NM -

Tattler 6/16PM

Volume XXXII • Number 24 • June 16, 2006 Conclave Learning Conference 2006: Future Tense. Marriott City Center/ Minneapolis. Rev. Al Sharpton, Gloria Steinem, Glenn Beck, & Terryl THE Brown Clemons. 14 Format Symposia. Over 40 sessions. $499 until July 1st, when the $599 walk-up rate will apply! To register for the 2006 Learning AIN TREET Conference or for questions on any Conclave program, call 952-927-4487 M S or visit www.theconclave.com. Communicator Network Clear Channel/Des Moines has launched AAA KPTL -“The Capital” - formerly occupying the frequency owned by Adult Hits KDRB. (KDRB shifted T AA TT TT LL EE R to “100.3 The Bus” a few weeks ago when KMXD flipped from AC.) The T R Bus continued broadcasting on its old frequency until the format was Publisher: Tom Kay Editor • Jess Treft launched under the guidance of CC National Triple A Format Brand Manager Cartoons Pilfered by Lenny Bronstein (and KTCZ/Minneapolis PD) Lauren Macleash. CC VP/Market Mgr. Joel McCrea said, “The incredible success of KDRB ‘The Bus’ prompted us to 1986-Main1986 Main Street’s 20th Anniversary-2006Anniversary 2006 move that station to a much stronger signal at 100.3FM. That created an opportunity to create something new for the market on the 106.3 frequency.” Syndicated talk show host Ed Schultz claims that “Republicans and He added, “People who liked KFMG, and before that KDMG, would like Conservatives” are conspiring to get him taken off Clear Channel Talk this station.”(KPTL is in the process of hiring at least three on-air WCKY-A/Cincinnati. -

Chicago Police and the Labor and Urban Crises of the Late Twentieth Century

The Patrolmen’s Revolt: Chicago Police and the Labor and Urban Crises of the Late Twentieth Century By Megan Marie Adams A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Robin Einhorn, Chair Professor Richard Candida-Smith Professor Kim Voss Fall 2012 1 Abstract The Patrolmen’s Revolt: Chicago Police and the Labor and Urban Crises of the Late Twentieth Century by Megan Marie Adams Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Robin Einhorn, Chair My dissertation uncovers a history of labor insurgency and civil rights activism organized by the lowest-ranking members of the Chicago police. From 1950 to 1984, dissenting police throughout the city reinvented themselves as protesters, workers, and politicians. Part of an emerging police labor movement, Chicago’s police embodied a larger story where, in an era of “law and order” politics, cities and police departments lost control of their police officers. My research shows how the collective action and political agendas of the Chicago police undermined the city’s Democratic machine and unionized an unlikely group of workers during labor’s steep decline. On the other hand, they both perpetuated and protested against racial inequalities in the city. To reconstruct the political realities and working lives of the Chicago police, the dissertation draws extensively from new and unprocessed archival sources, including aldermanic papers, records of the Afro-American Patrolman’s League, and previously unused collections documenting police rituals and subcultures. -

A Marxist-Leninist Framework Part Two

Marxism-Leninism Currents Today 1 Kurdistan – A Marxist-Leninist Framework Part Two Preface The intersection of the four countries of Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Syria, lies in Kurdistan. As Kurdistan is within these borders, all these must be considered, in any sensible work on the Kurdish national movements. Iran and the Mahabad Republic, in relation to the Kurds, were discussed in Part One. Here in Part Two, we will focus upon Iraq and Turkey, highlighting history relevant to the Kurdish national movement. Part Three will focus upon Syria. In assessing the Kurdish struggles, it is impossible to avoid the details of what now makes up the entire Middle East battle-ground. This term - ‘battle-ground’ - is not hyperbole. For the Middle East now embroils both major imperialists (USA, Russia), and the hitherto client states. The latter are now capable of exerting their own agency to varying extents. Iran, Saudi Arabia, Israel, Gulf States, Turkey – while generally subservient to a dominant state (For most of these it is the USA, or in the case of Iran and Syria, it is a co-equal status with Russia) – also have their own separate interests that they pursue. Disentangling these knots is difficult. Hence any history of modern day Kurdish struggles – appears to drown in details of the “Middle East”. We saw in Part One of this work, that the years up to 1946 were bitter for Kurds. But they were to be no less bitter, in the remainder of the 20th century. The prior era set the Ottoman, Russian Imperial and British Empires upon the Kurds. -

Ascertainment Report Jul-Aug-Sept 2009

Quarterly Programming Report June - September 2009 KPCC / KPCV / KUOR Date Key Synopsis Guest/Reporter Duration 7/1/09 SAC Lawmakers miss budget deadline, Controller to begin issuing IOUs CC :13 7/1/09 LAW LAPD Officers disciplined for involvement in May Day Melee Julian :48 7/1/09 SAC New budget year began at midnight, no budget deal in place Myers 3:37 7/1/09 SAC Lawmakers fail to pass budget that could have kept CA from issuing IOUs Small 2:40 7/1/09 POLI Mayor sworn in today Stoltze 4:34 7/1/09 POLI Frank Stoltze on Mayor Villaraigosa's second inaugural Stoltze :60 7/1/09 POLI Frank Stoltze on Mayor Villaraigosa's second inaugural Stoltze 1:09 7/1/09 SAC Governor declares fiscal emergency CC :22 7/1/09 ART LACMA's tight budget means fewer touring exhibitions in town CC :26 7/1/09 SAC Governor declares fiscal emergency, urges banks to accept IOUs CC :16 7/1/09 EDU Birmingham High School seeks charter status CC :25 7/1/09 LAW LAPD will not fire officers for diciplinary breaches in MacArthur Park incident CC :11 7/1/09 IE Riverside County fire officials issue fireworks warning to residents CC :21 7/1/09 HEAL Watchdog group sues state agency over care for kids with autism CC :18 7/1/09 POLI Frank Stoltze on Mayor Villaraigosa's second inaugural Stoltze 1:12 7/1/09 POLI State assembly speaker laments that there's no budget deal yet CC :22 7/1/09 POLI California assembly speaker tries to explain the budget debacle CC :26 7/1/09 POLI Alex Cohen talks with Julie Small about latest on budget, IOUs Small 4:20 7/1/09 ARTS Marc Haefele talks -

Journalism Awards

FIFTIETH FIFTIETHANNUAL 5ANNUAL 0SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA JOURNALISM AWARDS LOS ANGELES PRESS CLUB th 50 Annual Awards for Editorial Southern California Journalism Awards Excellence in 2007 and Los Angeles Press Club A non-profit organization with 501(c)(3) status Tax ID 01-0761875 Honorary Awards 4773 Hollywood Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90027 for 2008 Phone: (323) 669-8081 Fax: (323) 669-8069 Internet: www.lapressclub.org E-mail: [email protected] THE PRESIDENT’S AWARD For Impact on Media PRESS CLUB OFFICERS Steve Lopez PRESIDENT: Chris Woodyard Los Angeles Times USA Today VICE PRESIDENT: Ezra Palmer Editor THE JOSEPH M. QUINN AWARD TREASURER: Anthea Raymond For Journalistic Excellence and Distinction Radio Reporter/Editor Ana Garcia 3 SECRETARY: Jon Beaupre Radio/TV Journalist, Educator Investigative Journalist and TV Anchor EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Diana Ljungaeus KNBC News International Journalist BOARD MEMBERS THE DANIEL PEARL AWARD Michael Collins, EnviroReporter.com For Courage and Integrity in Journalism Jane Engle, Los Angeles Times Bob Woodruff Jahan Hassan, Ekush (Bengali newspaper) Rory Johnston, Freelance Veteran Correspondent and TV Anchor Will Lewis, KCRW ABC Fred Mamoun, KNBC-4News Jon Regardie, LA Downtown News Jill Stewart, LA Weekly George White, UCLA Adam Wilkenfeld, Independent TV Producer Theresa Adams, Student Representative ADVISORY BOARD Alex Ben Block, Entertainment Historian Patt Morrison, LA Times/KPCC PUBLICIST Edward Headington ADMINISTRATOR Wendy Hughes th 50 Annual Southern California Journalism Awards -

State of Florida REMP

Supplemental Information Withhold under 10 CFR 2.390 as “Sensitive-Federal, State, Foreign Government and International Agency Controlled.” State of Florida Radiological Emergency Management Plan (Annex A to State Comprehensive Emergency Plan) (July 2008) – w/o Appendixes THE STATE OF FLORIDA RADIOLOGICAL EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT PLAN Annex A to the State Comprehensive Emergency Management Plan FLORIDA DIVISION OF EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT 2555 SHUMARD OAK BOULEVARD TALLAHASSEE,FLORIDA 32399-2100 850.413.9969 State of Florida Radiological Emergency Management Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS SUBJECT PAGE Executive Summary ............................................................................................... v Local Authorities .................................................................................................... vii Definitions .............................................................................................................. viii Cross References to Nuclear Regulation - 0654/Federal Emergency Management Agency Radiological Emergency Preparedness, Revision #1 ............................... xi CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION Purpose and Scope ........................................................................................ 1-1 Assumptions ................................................................................................... 1-1 Emergency Planning Zones............................................................................ 1-2 CHAPTER 2 - THE RADIOLOGICAL RESPONSE ORGANIZATION General .......................................................................................................... -

Detection and Geo-Temporal Tracking of Important Topics in News Texts

Detection and Geo-temporal Tracking of Important Topics in News Texts Erik Michael Leal Wennberg Dissertation for the achievement of the degree: Master in Information Systems and Computer Engineering Jury Chairperson: Prof. Antonio´ Manuel Ferreira Rito da Silva Supervisor: Prof. Bruno Emanuel da Graca Martins Co - supervisor: Prof. Pavel´ Pereira Calado Member of the Committee: Prof. David Manuel Martins de Matos November 2011 placeholder placeholder placeholder Abstract In our current society, newswire documents are in constant development and their growth has been increasing every time more rapidly. Due to the overwhelming diversity of concerns of each population, it would be interesting to discover within a certain topic of interest, where and when its important events took place. This thesis attempts to develop a new approach to detect and track important events over time and space, by analyzing the topics of a collection of newswire documents. This approach com- bines the collection’s associated topics (manual assigned topics or automatically generated top- ics using a probabilistic topic model) with the associated spatial and temporal metadata of each document, in order to be able to analyze the collection’s topics over time with time series, as well as over space with geographic maps displaying the geographic distribution of each topic. By examining each of the topic’s spatial and temporal distributions, it was possible to correlate the topic’s spatial and temporal trend with occurrence of important events. By conducting several experiments on a large collection of newswire documents, it was concluded that the proposed approach can effectively enable to detect and track important events over time and space. -

2021 Iheartradio Music Festival Win Before You Can Buy Flyaway Sweepstakes Appendix a - Participating Stations

2021 iHeartRadio Music Festival Win Before You Can Buy Flyaway Sweepstakes Appendix A - Participating Stations Station Market Station Website Office Phone Mailing Address WHLO-AM Akron, OH 640whlo.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-FM Akron, OH sunny1017.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WHOF-HD2 Akron, OH cantonsnewcountry.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WKDD-FM Akron, OH wkdd.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WRQK-FM Akron, OH wrqk.iheart.com 330-492-4700 7755 Freedom Avenue, North Canton OH 44720 WGY-AM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WGY-FM Albany, NY wgy.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WKKF-FM Albany, NY kiss1023.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WOFX-AM Albany, NY foxsports980.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WPYX-FM Albany, NY pyx106.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-FM Albany, NY 995theriver.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WRVE-HD2 Albany, NY wildcountry999.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 WTRY-FM Albany, NY 983try.iheart.com 518-452-4800 1203 Troy Schenectady Rd., Latham NY 12110 KABQ-AM Albuquerque, NM abqtalk.iheart.com 505-830-6400 5411 Jefferson NE, Ste 100, Albuquerque, NM 87109 KABQ-FM Albuquerque, NM hotabq.iheart.com 505-830-6400